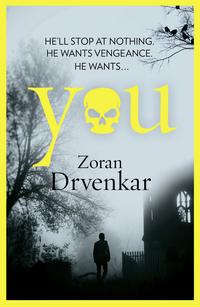

Czytaj książkę: «You»

About the Book

When a snowstorm halts traffic on a German autobahn, drivers are forced to spend the night in their cars. As day breaks, scores of people are found dead. Theories are rife. Was it an argument? Was it drugs, revenge or madness?

At first everyone agrees that several people must have acted together. No-one could have committed such an atrocity alone.

It is only over time that theories come to focus on an individual perpetrator, and the Traveller is born.

As he makes his way across a country gripped by fear, he’s searching for his next victim…

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Originally published in German as Du by Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin in 2010.

Copyright © Zoran Drvenkar 2010, © 2010 Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH

Translated from Du (German translation) by Shaun Whiteside

This edition published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

Zoran Drvenkar asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007465262

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007465286

Version: 2015-04-23

Praise for Zoran Drvenkar:

‘The kind of thriller, the kind of novel, that doesn’t come along every day … Stunning … Sorry thrills, and it thrills immaculately’ New York Times Book Review

‘As dark a novel as I have read in years … for those with quick minds and strong stomachs, Sorry is an impressive debut’ The Times

‘Very dark, very sinister, very original’ Joanne Harris

‘Shocking, compelling, disturbing’ Michael Robotham, author of Say You’re Sorry

‘Taut, tense and terrific’ Sean Black, author of The Innocent

Dedication

for YOU

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Zoran Drvenkar

Dedication

Part One

I

The Traveler

Ragnar

Stink

Ruth

Nessi

Schnappi

Stink

Schnappi

II

The Traveler

Ragnar

Mirko

Taja

Nessi

Schnappi

Ruth

Stink

III

The Traveler

Ragnar

Mirko

Taja

Oskar

Stink

Ruth

Mirko

Darian

Ruth

Stink

Nessi

Schnappi

Oskar

Ragnar

Part Two

I

The Traveler

Neil

Ragnar

Oswald & Bruno

Neil

Darian

Neil

Ragnar

II

The Traveler

Nessi

Tanner

Stink

Marten

III

The Traveler

Darian

Marten

Ragnar

Schnappi

The Traveler

Part Three

The Traveler

Taja

Darian

Nessi

Darian

Schnappi

Ragnar

Stink

Taja

Darian

Schnappi

Darian

The Traveler

Taja

Stink

Darian

Schnappi

Taja

Nessi

Neil

Stink

Ragnar

The Traveler

My Thanks To

A Note About the Author

A Note About the Translator

Read on for an extended extract of Zoran Drvenkar’s chilling début thriller, Sorry

About the Publisher

PART ONE

I

did you ever know

there’s a light inside your bones

Ghinzu BLOW

THE TRAVELER

As much as we strive toward the light, we still want to be embraced by the shadow. The very same yearning that craves harmony, craves in a dark chamber of our heart chaos. We need that chaos in reasonable portions, because we don’t want to turn into barbarians. But barbarians are what we become as soon as our world falls apart. Chaos is only ever a blink away.

Never have thoughts made waves so fast. Stories are no longer passed on orally, they are transmitted to us at breakneck speed in kilobytes, so that we can’t turn our eyes away. And if it gets unbearable, we react as the barbarians did, and turn that chaos into myths.

One of those myths was created in the winter fourteen years ago, on the A4 between Bad Hersfeld and Eisenach. We won’t write down the exact date; anyone can do the research for themselves. And in any case, myths don’t stick to dates; they are timeless and become the Here and Now. We return to the past and make it Now.

It is November.

It is 1995.

It is night.

The traffic jam has been growing for an hour now, thinning into three lanes, then two, and finally one, before it comes to a standstill. The highway is blocked by snow for over twenty miles. You can only see a few yards ahead. The snowplows creep along the secondary roads toward the traffic jam, and get stuck themselves. The skies are raging. The headlights look like lights under water. It isn’t a night to be out and about. No one was prepared for this change in the weather.

People are stuck in their cars. At first they keep the engine running and search optimistically for a radio station to tell them that the traffic jam will soon be over. They search in vain. It’s one o’clock in the morning, there’s no sign for an exit, and if there was one it would be impassable anyway. Standstill. The headlights go out one after the other. Engines fall silent, the only sounds are the wind and the falling snow. Coats are pulled on, seats reclined. There is an inconsistent rhythm—the cars start up, the heating stays on for several minutes, before the engines fall silent once more.

You are one of many. You are alone and waiting. Your navigation system tells you you are an hour and fifty-seven minutes from your house. You can’t believe this is actually happening to you. That this can be happening to anyone in this country. A simple traffic jam and nothing goes.

You’re one of the few people letting their engines run uninterrupted. Not because you’re cold. You know that as soon as the silence envelops you, resignation will set in, and you’re not the kind of person to give up willingly. You even leave the satnav turned on and study the display, as if the distance from your destination might be reduced by some miracle. And the more you look at the screen, the more you wonder how something like this can happen to you.

One thousand one hundred and seventy-eight people are asking themselves the same question tonight. They’re sitting there uncomfortably and cursing their decision to set off so late. In the end they give up and come to terms with the situation. Not you. Your engine runs for two and a half hours before you turn the key and are engulfed in silence. Your gas is running low. The satnav turns off. No light, no radio. Every few minutes you turn on the windshield wiper to sweep away the snow. You want to see what’s going on out there.

And that’s why you see the first snowplow parting the snow on the opposite side of the road. It looks like a weary creature dragging the whole world slowly behind it. At the side of the road the snow makes waves that immediately freeze. If they’re clearing one side, then they’re bound to be working on ours too, you think, and study the snowplow in the side-view mirror until only the glimmer of the taillights can be seen. It’s only then that you close your eyes and take a deep breath.

Years ago, your sister gave you a yoga course as a present, and some of the exercises stayed with you. You go inside yourself and meditate. You become part of the silence and within a few minutes you fall asleep. An hour later your windows are white with snow, and a pale light fills the car, as if you were sitting inside an egg. The cold hurts your head. The windshield wipers have stopped moving. You rub your eyes and decide to get out. You want to free the windshield from snow and see if there’s any sign of a snowplow up ahead.

The disappointment is as keen as the cold. You stand next to your car, and in front of you there’s only darkness and behind you there’s only darkness. I’m a part of it, you think, and wait and hope for a gleam of light and suddenly you burst out laughing. Alone, I’m completely alone. Only the wind keeps you company. The wind, the snow, and the desperate peace of cars that are stuck. The laughter hurts your face; you should move, otherwise you’ll freeze.

You take your coat off the backseat. Needles of ice hammer down on you, snowflakes press against your lips. You put on gloves, take a deep breath, and feel surprisingly whole. As if your existence had been striving for that moment—you, getting out of the car; you, turning around and feeling the falling snow and smiling. It’s a good smile. It hurts less than laughing.

A truck creeps past in the opposite lane and flashes once as if to greet you. Its tailwind reaches you with full force seconds later. You don’t duck; you feel the wetness on your face, stumbling slightly and wondering why you can’t wipe this stupid grin off your face. The truck disappears, and you’re still there looking at the apparently endless snake of vehicles in front of you disappearing into the darkness. You turn around and look at the darkness behind you. Nineteen years, you think, it’s nineteen years since I felt like this. You wonder how so much time could pass, and decide not to wait another nineteen years before continuing your search.

I’m in the Here, and the Here is Now.

You can’t go forward, so you decide to go back.

In the months that follow, there were countless theories about what happened that night. Was it an argument? Was it drugs, revenge, or madness? Some people thought it had something to do with the moon, others quoted from the Bible—but there was no sign of the moon that night, and if there is a God, he was looking the other way. There were all kinds of conjectures, everyone had a theory, and that’s how the myth came about.

At first everyone agreed that several people must have been acting together. No human being could have done all that on his own. It was only over time that theories came to focus on an individual perpetrator, and the Traveler was born.

Some people thought it would never have come to an end if the snowfall hadn’t suddenly stopped. Others suspected there was a system behind it.

Many claimed the Traveler got tired.

Conjectures through and through.

You go to the car behind you and get in on the passenger side. The windows are covered with snow. You don’t have to look. You know what you’re doing and leave the car three minutes later.

You leave the second car after four minutes.

You skip the fourth and fifth cars because there’s more than one person in them. How can you tell when the passenger seat is empty? Perhaps it’s instinct, perhaps it’s luck. Two men are asleep in the fourth car, and in the fifth there’s a family with a dog. The dog is the only one awake, and sees you passing the window like a shadow. It starts whimpering and pees on the seat.

In car number ten you encounter your first problem.

A woman sits wrapped up at the steering wheel. She can’t sleep, she’s absolutely freezing because she’s too stingy to turn on the engine even for a moment. She’s wearing three pullovers and her coat over the top. Her car windows are damp on the inside, the drops of condensation are frozen. The woman’s face is sore with cold. Her hands are claws. She regrets not bringing any drugs along. A sleeping tablet or two and it would all be more bearable.

The woman gives a start when the passenger door opens. For a moment she thinks it’s the emergency services bringing her blankets and a thermos. She’s about to complain because it’s taken so long.

“Don’t panic,” you say and close the door behind you.

You smell her body, the fading deodorant. You smell her weariness and frustration, it is clammy and sour and leaves her mouth with every breath. She asks who you are. She tries to shrink away from you. Her eyes are wide. Her throat feels brittle under your hand. The inside light goes off. You press the woman against the driver’s door, you put your whole weight into the movement—your left arm stretched out as if to keep her at a distance. You don’t take your eyes off her for a second, feeling her blows against your arm, against your shoulder, watching her hands change from claws to panicked, fluttering birds. She gasps, she chokes, then her right hand finds the ignition key and starts the engine. You weren’t expecting that. In car number six the driver tried to climb onto the backseat. In car number eight the driver repeatedly banged his head against the window to draw attention. None of them tried to drive away.

The woman puts her foot on the accelerator; the car’s set to Park. The engine roars and nothing else happens. She hits the horn; the honking sounds like the bleating of a lost sheep. You clench your right hand and strike the woman in the face. Again and again. Her jaw breaks, her face slips to the left and she slumps in on herself. You lower your fist, but you keep the other hand on her throat. You feel her bones shifting under your strength. You feel the life escaping from her. That is the moment you let go of her and turn off the engine. It took less than four minutes.

The Traveler moves on.

In car number seventeen an old man is waiting for you. He’s belted in and sitting upright as if the journey is going to continue at any moment. There’s classical music on the radio.

“I was waiting,” the old man said.

You close the door behind you; the old man goes on talking.

“I saw you. A truck went past. The headlights shone through the windows of the car in front of me. I saw you through the snow. And now you’re here. And I’m not scared.”

“Thank you,” you tell him.

The old man unbuckles his seat belt. He shuts his eyes and lets his head fall onto the steering wheel as if he wants to go to sleep. The back of his neck is exposed. You see a gold chain cutting through his tensed skin like a thin thread. You put your hands around the old man’s head. A jerk, a rough crack, a sigh escapes from the old man. You leave your hands on his head for a while, as if you could catch his fleeing thoughts. It’s a perfect moment of peace.

The next day on the news they talk about an organization. The police were trying to make a connection between the twenty-six victims. The families were grieving, everywhere in the country flags were flown at half mast. They were talking about terrorists and the Russian mafia. They were thinking about a cult; the subject of sects was given prominence once again. Only the gun lobby didn’t get involved, because no guns had been used. Whatever was said, whatever people conjectured, no one dared to use the phrase “mass murder.” It never takes long. Eventually a tabloid newspaper put it in great big letters on the front page.

MASS MURDER ON THE A4.

It was a dark winter for Germany.

The big question on everyone’s mind was what made the Traveler get out of the twenty-sixth car and think, Enough’s enough. Did he really think that? Did he hear a voice, did demons speak to him, or did he get bored? Whatever the answer, it had nothing to do with the snowfall, because the snow went on falling till dawn. No, the truth isn’t complicated, it’s relatively simple.

You leave the twenty-sixth car and don’t think anything at all. You feel the wind and you feel the cold and you feel safe and you’re moving to the next car when you notice a glimmer on the horizon. Perhaps the snowfall is reflecting a light in the far distance. Whatever it is, it makes you turn around and set off back to your car. You follow your own overblown track and it is opening up like an old wound. At your car you wipe the windshield free of snow and sit down behind the steering wheel. You take a deep breath, put thumb and index finger around the ignition key, and wait. You wait for the right moment. When you start the engine, the cars in front of you come to life, and the headlights of over a hundred vehicles light the blocked motorway with a pale light. After exactly four hours the traffic jam gets moving again, because the Traveler was waiting for the right moment.

You put the car in gear and you’re very pleased with yourself. The pain and throbbing in your hands are insignificant. Later you will discover that you’ve broken two fingers on your right hand, and in spite of your gloves the knuckles on both hands are swollen and beaten bloody. Your shoulders ache from the uncomfortable posture you assumed in the cars, but none of that matters, because there’s this indescribable contentment within you. There’s also a sweet taste in your mouth that you can’t explain. The taste prompts a memory. The memory is nineteen years old. Glorious, dazzling, sweet. You know what it all means. You thought the search was over, but it had only taken a breather. It’s the start of a new era. Or in other words—the beginning of the end of civilization as you know it.

In retrospect you still like that thought best.

No beginning without an end. A man gets out of his car, a man gets back into his car, and the traffic jam in front of him slowly starts to move. The Traveler travels on.

RAGNAR

This isn’t the end, and a beginning looks different. This is the moment in between, when everything still looks possible. Retreat or attack. We’re in the present. It’s eight o’clock in the morning. The spotlights are turned on you, because this Friday morning you’re making a decision that will change all your lives, as you are standing at the edge of the pool unable to believe your eyes. The light gleams blue and cold up at you. What you are seeing is a soundless nightmare. Not one of you dares to break the silence.

You wish you were far, far away.

Leo has moved back a step; he is waiting for your reaction. His hands are deep in the pockets of his jacket and he’s struggling to stay still. David is standing on the other side of the pool, rubbing the back of his head. He’s only been working for you for three months, and you’re still not sure what to make of him. He’s young, he’s ambitious, and he’s one of Tanner’s many grandchildren. Family means nothing to you. You wanted to give the boy a chance, because Tanner is putting his hand in the fire for him. It’s the only kind of family bond that you respect.

You take a deep breath. The air is warm and clean, the air-conditioning system is working without a sound. Oskar had the arched basement dug out four years ago. Walls and ceiling are new and covered with terra-cotta tiles. They don’t just reflect the light; every breath is clearly audible and echoes in the silence like the panting of dogs. Your hands tingle. You want to hit something, a bag of sand or just the wall. Something.

How could she?

You rub your eyes before you look again. You still don’t believe it. Leo shifts uneasily from one leg to the other; he knows there’s going to be trouble soon. A whole lot of trouble.

“I don’t believe it,” you say.

“Maybe—”

You raise your hand, Leo falls silent, you turn to David.

“What do you think how much is it?”

“Thirty, maybe forty kilos, it’s hard to say.”

Footsteps can be heard from the floor above, none of you is looking up, you are standing motionlessly around the pool. On the surface of the water you can see your elongated reflections quiver slightly. Maybe there’s an underground line nearby, or else one of those massive great trucks is dragging itself along a side street and sending its vibrations far underground. Your faces look like the faces of ghosts that have seen everything and are tired of being ghosts. Tired is exactly the right word, you think, because you’re seriously tired of all this bullshit. You felt something dark coming your way, you should have been prepared, but who expects something like this?

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” says David.

“And you should never have seen anything like this,” you reply and hear Tanner coming downstairs. He stops some distance behind you. Tanner is your right hand; without him you’d only be worth half of what you are. He turns sixty next year and wants to retire slowly. You have no idea what you’ll do without him. He taught you everything you know, and it’s only when he’s no longer there that you’ll find out whether you can cope on your own. One of your customers once said that Tanner scared him because he didn’t emit anything at all. Tanner’s a transmitter who only transmits when he feels like it. Now, for example. He says, “Nothing. It’s gone. She’s taken all of it.”

You don’t react; what should you say to that? “Thanks” would be inappropriate. The quivering on the surface of the water vanishes. You look up from the pool. Your fury and frustration need an outlet. So far you’ve ignored Oskar. You didn’t want to talk to him, you couldn’t even look at him because the mere sight of him would have made you explode. This is all his fault. Correction. His and yours, if you’re honest. You should never have done business together.

Never.

Take a look at him, how peacefully he is sleeping there on that stupid leather armchair as if he hadn’t a care in the world. It’s eight o’clock in the morning, and you wouldn’t be surprised if he was drunk.

“Wake him up.”

Leo bends over Oskar and shakes him. No reaction. Leo slaps him in the face with the palm of his hand. Once, twice, then he steps back. It doesn’t suit him. When Leo takes a step back, it means there’s a problem. You react immediately. Your bodily functions are shutting down. The breathing, the heartbeat. Your blood is flowing slower, your thoughts move like molasses. Reptile, I’m turning into a fucking reptile, you think, when Leo confirms what you were thinking: “He’s gone.”

A few steps and you’re beside Oskar, crouching down in front of him. His skin is pale and shiny in places. It reminds you of dried sushi.

“What’s up with his skin?”

“That’s ice.”

Leo holds his hand out to you; his fingertips are damp.

“He must have frozen to death.”

You want to laugh. It’s over twenty degrees down here, and out there it’s early summer. No one just freezes in the summer, you want to say, but not a word comes out. David comes and stands next to you. You’d rather he kept his distance. It’s your own fault. David is anxious for your acknowledgment, and you aren’t making it easy for him.

“May I?”

You nod, David crouches beside you and taps Oskar’s forehead, there’s a dull tok. David looks for a pulse and then shakes his head.

“Leo’s right. Oskar’s gone.”

You feel Tanner’s and Leo’s eyes on your back, and David is looking at you too. There’s nothing to say, your mind is blank. Oskar deep-frozen on a chair, the vanished merchandise, and then this fucked-up swimming pool. When you can speak again, you say, “I want her to suffer.”

“I’ll see to it,” David replies.

The answer comes too quickly. David wasn’t thinking, even though an order like that doesn’t call for much thinking. He reacted automatically. You hate that. Your men should think and not react.

Both of you get up at the same time; you’re close to one another, so that you can smell his breath.

“David, what did I just say?”

“That she—that she should suffer?”

You grab him between the legs. He tries to move away, thinks better of it and stands still. Only his torso bends slightly forward, that’s all that happens. You press hard.

“What is that, David?”

Sweat appears on his forehead; his answer is a gasp.

“Suffering?”

“No. This isn’t suffering, David. Suffering is when I pull your balls off and let you dive after them in the pool, that would be suffering. Now do you understand what I meant when I said she should suffer?”

“I understand.”

You let go of him. His nostrils are flared, a tear runs down his cheek, his chin is trembling. David is twenty-four, you’re nineteen years older. You understand each other.

“Bring me the boy.”

“But where are we supposed to—”

“Ask Darian,” you interrupt. “He’ll know where you can find him. And David, this is serious. Leave no stone unturned and don’t even think about coming back here without the boy.”

You turn to Tanner.

“Go with him. Leo and I will wait here. You’ve got an hour.”

Tanner nods and leaves with David. You tell Leo to get two chairs. Leo disappears too. At last you’re alone with Oskar, and the tension leaves you and is replaced with a heavy weariness. It should never have come to this, you think, and although you are weary you still want to yell at Oskar and behave like an idiot. He’s gone. Leo couldn’t have put it more appropriately. Once you’re gone, it’s final. It has no beginning, it just has an end. You put your hand on Oskar’s head for a moment. His hair feels greasy; through his scalp you can feel the cold emanating from his body.

What on earth happened to you?

You lift one eyelid as if his gaze might tell you what’s happened here. Come on, talk to me. Nothing. The gaze of a dead man is the gaze of a dead man. It isn’t the first time you’ve seen it. When you let go of the lid again, it closes very slowly.

Leo comes down with the chairs and says, “Christ, it stinks up there.”

You sit down opposite Oskar. Leo’s bulk obscures the chair next to you. Eight years ago, he was still in the ring and it was shaming. As a young man Leo had been national champion twice in a row, then the fire went out, and everyone apart from Leo noticed it. He kept going. When a man turns forty, he can stand wherever he wants, just not in the ring. Leo was one of those stubborn guys whose brain can come trickling out of their ears and they just pull back their shoulders and go on boxing. His second passion almost cost him his life. His gambling debts were in six figures, and if it hadn’t been for Tanner, Leo would have had to go on tour—Thailand and Indonesia loved European flesh. Fights without rules, but the money was good. Tanner bought the aging boxer’s freedom and saved him. Since then Leo’s been working for you and he is at the same time Tanner’s shadow. You don’t know what kind of aftereffects boxing left him with. His face is scarred, most of his nerves don’t work, the hands are deformed paws. He is married to a former model. She treats him like a god. You know you can always rely on Leo. He’s loyal and he can take a beating like no one else. And he hardly misses a thing.

“There’s no TV.”

“So?”

Leo points at Oskar.

“If there’s no TV, then how come Oskar’s holding a TV remote?”

You’re surprised; you hadn’t noticed the remote control. It sticks out from his fingers like a black popsicle. Focus—how could you have overlooked something like that? You bend forward and take Oskar’s hand in yours. For his last birthday you gave him three watches and a watch winder. Oskar was allowed to choose the watches, the watch winder was your department. Its frame is covered with black piano lacquer, and as soon as you touch it, four little lights come on inside. You remember Oskar calling you up after his birthday party and telling you he’d spent an hour sitting in front of the box looking at the watches being rocked to sleep.

There were days when Oskar was like a ten-year-old. What he hadn’t been able to experience as a child, he’d more than made up for as a grown-up. And you were always by his side, like a proud uncle with an overflowing billfold.

The watch on Oskar’s wrist cost you ten grand, but it’s still not cold-resistant. The date tells you that Oskar was deep frozen on Saturday. The watch stopped at twenty to twelve.

Leo asks you if you have any idea what might have happened down here.