Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Butterfly Winter»

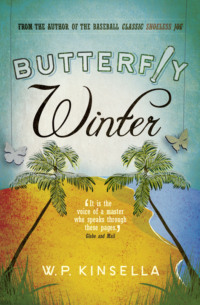

W.P. KINSELLA

Butterfly Winter

For Barbara Lynn Turner Kinsella

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: The Wizard

Chapter One: The Wizard

Chapter Two: The Wizard

Chapter Three: The Wizard

Chapter Four: The Wizard

Chapter Five: The Wizard

Chapter Six: The Wizard

Chapter Seven: The Wizard

Chapter Eight: The Wizard

Chapter Nine: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Ten: The Wizard

Chapter Eleven: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Twelve: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirteen: The Wizard

Chapter Fourteen: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Fifteen: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Sixteen: Esteban Pimental

Chapter Seventeen: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Eighteen: The Wizard

Chapter Nineteen: The Wizard

Chapter Twenty: The Wizard

Chapter Twenty-One: Hector Pimental

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Gringo Journalist

Part Two: Butterfly Winter

Chapter Twenty-Four: Ali

Chapter Twenty-Five: Fernandella Pimental

Chapter Twenty-Six: The Wizard

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty-One: The Wizard

Chapter Thirty-Two: Julio Pimental

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty-Four: The Wizard

Chapter Thirty-Five: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty-Six: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty-Seven: The Wizard

Chapter Thirty-Eight: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Thirty-Nine: The Wizard

Chapter Forty: The Wizard

Chapter Forty-One: The Wizard

Chapter Forty-Two: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Forty-Three: The Wizard

Chapter Forty-Four: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Forty-Five: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Forty-Six: The Wizard

Chapter Forty-Seven: The Gringo Journalist

Part Three: The Wound Factory

Chapter Forty-Eight: The Wizard

Chapter Forty-Nine: An excerpt from a chapter of a novel written by the Wizard

Chapter Fifty: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Fifty-One: Milan Garza

Chapter Fifty-Two: Quita Garza

Chapter Fifty-Three: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Fifty-Four: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Fifty-Five: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Fifty-Six: The Wizard

Chapter Fifty-Seven: The Wizard

Chapter Fifty-Eight: The Wizard

Chapter Fifty-Nine: Dr Lucius Noir

Chapter Sixty: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Sixty-One: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Sixty-Two: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Sixty-Three: Julio Pimental

Chapter Sixty-Four: The Wizard

Chapter Sixty-Five: The Wizard

Chapter Sixty-Six: The Wizard

Chapter Sixty-Seven: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Sixty-Eight: The Wizard

Chapter Sixty-Nine: The Wizard

Chapter Seventy: The Wizard

Chapter Seventy-One: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Two: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Three: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Four: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Five: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Six: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Seven: The Gringo Journalist

Chapter Seventy-Eight: The Wizard

Acknowledgements

Also by W. P. Kinsella

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE

The Wizard

‘… anything that can be imagined exists.’

—WHAT THE CROW SAID, ROBERT KROETSCH

‘The word chronological is not in the Courteguayan language, neither is sequence. Things happen. That is all there is to it. In most other places, time is like a long highway with you standing in the middle of a straightaway while the highway dissolves in the distance in both directions, past and future. In Courteguay, if you picture the same scene, time occasionally runs crossways so that something that will happen in the future might already be behind you, slowly receding, while something from the past may not yet have happened.’

—THE WIZARD

ONE

The Wizard

‘You appear to be a man in your late 60s,’ the Gringo Journalist says. ‘I have always been what I appear to be,’ replies the Wizard. ‘And,’ he adds, the words barely audible under his creaking breath, ‘I always tell people what they want to hear, whether it is truth or fiction.’

‘I am told that you move from place to place as if by magic,’ the Gringo Journalist continues.

‘There is no magic, there are no gods,’ says the Wizard.

‘You are currently referred to as a wizard, even by your enemies.’

‘It takes a wizard to know there are none,’ says the Wizard.

The Wizard lies in a high, white hospital bed. The room is banked with flowers, bouquets made up of various combinations of the eleven national flowers of Courteguay. The Wizard stares up at the Gringo Journalist, who is lean and blond, holding a sleek black tape recorder toward the Wizard as if he were offering a bite from a sandwich.

The Wizard, who has discarded his hospital garb, is wearing a midnight-blue caftan covered in mysterious silver symbols that look like what a comic strip artist might use to intimate curse words, and insists on being paid for the interview, not in Courteguayan guilermos, but in American dollars. He forces a smile for the Gringo Journalist, his gimlet eyes twinkling.

‘Interviews are so tiring. Even wizards die, did you know that?’

The morning air is cool and lustrous, rife with possibilities, silvered with deception, tasty as fresh lime.

‘Here I am. Cool pillows, a clean room, a ceiling fan. And I still have a listener, something terribly important to one who is a storyteller. An excellent way to die. I close my eyes and my long life slides by like a newsreel, like a canoe floating on placid water. The room is liquid with memories. Me, planting baseballs like seed corn, waiting for the stadiums to grow and flourish.

‘My enemies, and they are many, will deny it all. Without me there would have been no Julio or Esteban Pimental; their father was a gambler but I was a better one. It is not something I am exactly proud of. But it is all connected, as everything is. Knee bone connected to the thigh bone. Now hear the word …’

The Gringo Journalist asks another question, watches the Wizard’s eyes, waiting. He wants to know how to find a place, a place important to his research.

‘My friend, it is very difficult to give directions in Courteguay. Objects have minds of their own. In the night houses sometimes slip across a street, or change places with a house a few doors away. One might go to bed in a home on the south bank of a river and wake in that same house but on the north bank, and the basement not even damp.

‘So, you want to know about Julio Pimental? Perhaps the greatest pitcher ever to play in the Major Leagues, certainly the greatest pitcher ever to come out of Courteguay. That is somewhat easier than giving directions. The rumors you have heard are true. Twin boys playing catch in the womb. An unusual event in many parts of the world, but not in Courteguay. Here the unusual is the norm. The sky once rained silken handkerchiefs. There was a woman with three breasts … a man with a square penis.

‘Well, you have come to the right person. The horse’s mouth so to speak. Speaking of the horse’s mouth did you know that there is a jungle spirit called a Loa that rides men like a horse? If you are unlucky enough to have a Loa land on your back it will run you until you collapse, if you are truly unlucky the Loa will ride you until you die.

‘Of course Loas are Haitian. But spirits do not recognize arbitrary boundaries, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Courteguay, they are all the same to a Loa.’

The Wizard takes a deep breath.

‘I’ve seen it all. Not always through my own eyes, of course. I’ve spied on armies through the eyes of a predator, overheard the strategies of the Insurgents while lying comfortably in the undergrowth in the guise of a buzzard munching on a Government soldier. I can smell out conspiracy. Through the ears of an ivory-feathered cockatoo I have overheard young girls’ secrets, eavesdropped on many a whispered plot, changed myself into a dewdrop and cooled a lovers back in the steamy dawn.

‘You look skeptical. You question my veracity? An old fool on his death bed, you think, wizened to half his size. An old fool who has been President of the Republic of Courteguay, several times. I was there when that other El Presidente – it is a travesty that the words El Presidente should be uttered in the same breath as the name Dr Lucius Noir, murderer of Quita Garza’s father. Ah, I thought that would get your attention. But do not jump to rash conclusions. In Courteguay El Presidente is an all encompassing statement. You will, I’m sure want to hear about Quita Garza and Julio Pimental. But before we get too far into the interview, I must warn you that the boundaries here are different. Never forget that. Never be surprised.’

The Gringo Journalist eyes the Wizard suspiciously, trying to find a suitable place to set the tape recorder, a recorder which he had to pay a bribe of three times its value just to bring into Courteguay. He gets no help from the Wizard. He finally swings the brown arborite arm that holds the food tray into position, across the middle of the bed, and places the tape recorder on it. The Wizard smiles again, the wrinkles around his eyes crinkling like crumpled newspaper. The old man coughs wetly.

‘I crouched among the plumeria when the evil deed was done. Oh, yes, I’ve seen it all.

‘It all began with the Wizard. If it wasn’t for the Wizard there wouldn’t be a story. You might say Courteguay began with the Wizard, with the coming of the Wizard, and the coming of baseball.

‘Excuse me? Of course I am the Wizard, at least today. May I not speak of myself in the third person? Is there some new government regulation against speaking of oneself in the third person? My mind, the Wizard’s mind, shifts constantly, my mind is like a record with a scratch, a tape with a flaw. Have you ever heard the name Jorge Blanco? Don’t answer. Of course you have. All politicians have to reinvent themselves occasionally. Ah, for the simplicity of life when I was Jorge Blanco. Before the twins were born, before the dark shadow of Dr Noir passed over Courteguay.

‘But who’s to say what is truth. People tell tales, and as the tales emerge they become as good as truth. In Courteguay, anything that can be imagined exists. The telling is the thing. Truth is spun like silk; truth is manufactured. Unlike you, a journalist, when I need facts I invent them. Here in Courteguay, the world is as it was meant to be, as it used to be everywhere before magic was hunted down, driven to the hinterlands, made extinct, like dazzling birds hunted for their beaks or feathers, or feet. People change, but shadows of their pasts remain behind, often have lives of their own.

‘Yes. Yes. I do tend to ramble. But if you want the whole story, bear with me. You gringo newsmen are too impatient. You want the entire account presented in one minute flat, you want the tale in digest form suitable for Courteguay Today.

‘It is? An imitator? I didn’t know that. So long since I’ve been to America. Well, they say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Besides, Courteguay has no copyright laws. I once published a book by this American fellow Hemingway, under my own name of course. It was very well received. I tried Shakespeare, a play called Othello, but though it has a wonderful plot it didn’t sell at all. The language needed to be modernized. Too bad there are not more people in Courteguay who can read. I might not have had to go into politics.

‘In Courteguay, whoever calls himself El Presidente is the law. A banana republic is how Courteguay is referred to in the international press. An irony. We do not grow bananas in Courteguay. Mangos, guava, passion fruit … A passion fruit republic. You ever hear of such a thing?

‘Yes. Yes. I do tend to ramble. Are you afraid I will die before you finish this interview? You pay your money. You take your chances. Didn’t someone in baseball say that? Leo Durocher? Casey Stengel? Yogi Bear?

‘Berra, of course. You will encounter this rumor eventually, if not already, so it is better you hear it from me. The reason the Wizard lives so long, people will tell you, my enemies, and there are many, possibly also my friends, is that he takes the future of others and appropriates it. He is there when a government soldier breathes his last – maybe that soldier had only four months to live, but the Wizard, his hand on the dying soldier’s chest, adds four months on the end of his own life. The Wizard, some will say, is like an ambulance-chasing lawyer, always there within minutes of the crash, his wizened hands leaving a veronica on the chests of the dying. Wizards live forever some people believe. Not me. You should try being a wizard sometime. Perhaps I could persuade you. As you can tell by my demeanor, I am in the market for a successor.

‘Has anyone told you of Dr Noir’s method of population control? No? Yes, I am getting ahead of myself, but bear with me. The contraceptive was much too slow for Dr Noir.

‘There are more people than there are mangos,’ he is reported to have said. ‘We cannot increase the number of mangos, therefore we must decrease the number of people.’ Consequently, Dr Noir decreed that anyone with the first name Tomas, who lived within a forty-mile radius of San Barnabas, the capital, was to be executed.

‘On the day Dr Lucius Noir seized power in Courteguay for the first time, became El Presidente, he decreed that as long as he was dictator all the mirrors in Courteguay would reflect only his image.

‘Children screamed. Women fainted. Mirrors were thrown into the streets.

‘I’m sorry. Back to Milan Garza for a moment. Milan Garza, a baseball immortal, Quita Garza’s father.’

‘But I was asking about Julio Pimental,’ says the Gringo Journalist.

‘Pay closer attention, please! I was there, lurking in the ferns, like a lion in a Rousseau painting, when the deed was done. Milan Garza overestimated his own importance, felt that being named a Baseball Immortal actually made him immortal. Bad mistake.

‘Later, camouflaged by a thousand funeral wreathes made from the eleven national flowers of Courteguay: bougainvillea, hibiscus, red and white plumeria, bird of paradise, orchids, poinsettias, anthurium, lehua, vanda orchids and ginger – did you get them all down? I forgot that black biscuit absorbs my words like the earth does rainwater. I listened to the evil man who called himself El Presidente, as he eulogized Milan Garza, then had him interred in a crystal-domed coffin at the Hall of Baseball Immortals.

‘But, again I am ahead of myself, it is the Wizard you want to hear about, amigo.’

‘I was asking about Julio Pimental.’

‘Time begins with the Wizard. I am speaking now as El Presidente. The President of Courteguay who began one of his lives as Jorge Blanco. With me you get three interviews for the price of one. Only in Courteguay.

‘To know Julio Pimental, and his twin, Esteban, you must first know the Wizard. Courteguay began with the Wizard, the coming of the Wizard, the coming of baseball. I knew him well. There was nothing mysterious about him originally. His name was Sandor Boatly, the surname having been anglicized on the spot by an immigration official when the threadbare Boatly family arrived in America from Europe, the spot being Ellis Island, the time being 1885. Sandor Boatly was nine years old, spoke only Hungarian, and the word baseball was not in his vocabulary, in any language.’

TWO

The Wizard

Sandor Boatly saw his first baseball game in Providence, Rhode Island in 1887, when he was eleven, and his experience that day was more emotional, more magical, more prophetic, more of a grand call to service than that of other boys his age who claimed to have had religious experiences which inspired calls to the priesthood.

His father, Szabo Boatly, a glazer by trade, worked long hours in a crockery factory. Saturday afternoon was his only time off, except for Sunday, a day reserved for pious inactivity. On Sunday the Boatly children were not even allowed to play with their home-made toys.

On a spring afternoon in 1887, the father took Sandor and one of several sisters, Evita, for a walk. A few blocks from their home, outside the Eastern European ghetto, they were attracted by crowd noises, and the clear sharp thwack of bat on ball. The sounds reminded Sandor of his early childhood in Hungary. As he listened he recalled the crack of a woodsman’s ax biting into a strong tree.

Sandor Boatly pleaded with his father to take the little family into the baseball park, and the father, being in a jolly mood, agreed. A man wearing a straw boater with a beautiful red sash collected fifteen cents from the father; the children were admitted free. Once inside the park they made their way down the right field line to a spot where they could see most of what was happening on the field.

The elder Boatly was expecting a soccer game. He had played rather well in the old country, if his accounts could be believed.

‘What is this?’ he kept repeating in Hungarian.

By then Sandor knew the word baseball. He had been exposed to childish versions of the game played on the streets, playgrounds and school yards of Providence. He had seen American boys trouping off after school, tossing a small hard ball in the air, wooden staves perched on their shoulders like rifles. But he had never seen a professional contest, never dreamed that grown men engaged in the game, playing it with deadly seriousness.

Sandor Boatly had never guessed that, properly played, baseball consisted of mathematics, geometry, art, philosophy, ballet and carnival, all intertwined like the mystical ribbons of color in a rainbow.

It was years before Sandor Boatly encountered a magician, but the thrill of seeing an orange turned into an endless string of bright silken scarves was nothing compared to what he experienced that afternoon.

There was a river to the left, the outfield sloped gently upward. There was no outfield fence. The game was unenclosed, the foul lines forever diverging.

‘Bah!’ said Sandor’s father, settling on his haunches, chewing on a blade of grass. ‘A stick and a rock. What kind of game is this?’

But Sandor understood instantly. He intuited that baseball was somehow akin to the faded picture on the wall of the Boatly living room where two ballerinas twirled on toes as stiff as inverted fence pickets. It was only a semi-professional baseball game they were witnessing, two local athletic clubs, one sponsored by the Sons of Erin, the other by the Christopher Columbus Society.

Sandor, transfixed, studied the pitcher and catcher, connected inexplicably by the rope of leather they tossed back and forth. He watched the infielders scurrying after ground balls, leaping like cats to take a grounder on a high bounce and brace themselves in mid-motion to throw out the sprinting runner at first base.

Somehow, as if by divine revelation, Sandor Boatly was filled with baseball expertise; he understood the aesthetics of the game and explained each play to his father and sister, who after an inning or two had taken to cheering for the Sons of Erin, while, like the rest of the crowd, deriding the single umpire who wore a tall silk hat, and stood like an undertaker behind the pitcher, from where he made all decisions concerning the game.

In the space of a few moments, Sandor had not only become enchanted by the magic of baseball, but came to understand it instinctively. But, miracle of miracles, he was able to communicate his newfound love to his father and sister.

‘Look! Look!’ he kept saying. ‘The field is not enclosed. The possibilities are endless. There is no whistle to suspend play, there is no clock to signal an ending.’

‘Look! Look!’ he must have repeated the words a thousand times that fateful afternoon. And when the game ended, the little family drifted dreamily away from the ballpark, the odor of fresh cut grass still in their nostrils, gauzy memories of plays that were and plays that might have been mingling in their minds.

It was Sandor’s father who, as they walked toward home on the gritty streets of Providence, Rhode Island, articulated the essence of baseball.

‘When,’ he asked his son, ‘may we return to this land of dreamy dreams?’

While his father remained a lifelong fan, Sandor Boatly dedicated his life to baseball. Instead of becoming a priest, as many of his boyhood friends did, Sandor Boatly became an evangelist of baseball, a Johnny Appleseed, who instead of flinging apple seeds in rainbow-like arcs as he walked the fields and backwoods of America, carried a strange and wondrous canvas sack across his shoulders so that at times he looked as though he was bearing a cross. The sack was filled with baseball bats, hand-carved from hickory, crafted with love to last forever, by men who knew and appreciated the feel of a smooth and sleek weapon, which like a gun, became an extension of the holder. The sack also contained baseballs, horsehide, handstitched with catgut, hand-wound by people who knew what they were building.

The day he turned fourteen, Sandor Boatly refused his father’s offer (it was more of a command) to become an apprentice glazer and contribute to the family finances. Sandor set out on his mission, which was to introduce the magic of baseball to those who did not know of it, or if they did know about baseball, to teach them to regard it with the reverence it deserved.

On foot, Sandor moved across Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, and eventually made his way to the plains of Iowa and Nebraska, where like a true evangelist he spread the word of baseball to the scattered multitudes.

Along the way he abandoned his name, for he found it took too much time to explain his ancestry, his recent history, his roots, for people were forever wondering if his family might have traveled to America with their family, plumbing the depths of their memories for common ground.

‘Call me whatever you like,’ Sandor said to his multitudes, which, on the prairies, consisted often of a single farm family, dirt farmers living in soddies, some living in virtual caves built into the sides of hills. Sandor would thump at the gunnysack-reinforced door of a soddy. The pale face that answered would shade its eyes from the sudden glare of the prairie. He was often mistaken for a preacher, for he dressed in black broadcloth, wore a wide-brimmed hat and, as soon as he was able, grew a bushy black beard.

After introducing himself, though not always his mission, for the tough pioneer women tended to frown on sport of any kind as frivolity, Sandor would find his way to where the men were working. He would pitch in and work side by side with the farmer and his sons, picking roots, or pulling stumps, perhaps carrying rocks to a homemade stoneboat, or walking behind an ox as it pulled a plow.

At the end of the day, by the fading rays of a low sun, or as the plains horizon flamed like prairie fire, Sandor would open his magical sack and toss a ball to a burly farm boy in work pants too short and clodhopper boots awkward as wood blocks. The three or four or five of them would lay out a rough diamond, perhaps using a barn wall as a backstop, if the homesteaders were fortunate enough to have built a barn. Sometimes there would be stumps for bases, with stringy trees in the outfield.

Often the only clear land would take in a slough, full of frog grass and cattails, where inches of water lay hidden under seemingly innocent greenery. But no matter the obstacles, Sandor’s enthusiasm would shine through, and the big, lumbering boys would get word to their neighbors, and by the second evening of his visit there would be almost enough players for a side of baseball.

Then Sandor would spring the trap. He would mention the last area that he had visited, five, or ten, or fifteen miles away, and he would mention how they had taken to the game, and how they had formed a team and were waiting only for a challenge.

When he moved on he would leave behind a precious ball, after painstakingly demonstrating to his converts how to re-cover it. He might also leave behind a bat, or he might simply show them how to hew a bat from a sturdy piece of timber. On rare occasions he would actually see the competition through, choosing a site, scheduling the contest, acting as umpire.

He learned early on that the main objections to his mission would be on religious grounds. Sandor was quick to realize that pioneers, facing unbelievable hardships, often clinging to life and sanity by the thinnest of threads, needed not only to believe in the supernatural, but to believe the supernatural was on their side. Sandor realized too, that these primitive peoples lacked the sophistication to realize that there were many and various manifestations of the supernatural, Sandor Boatly himself being one.

Since he was often mistaken, on first contact, for a circuit rider, Sandor took to carrying a heavy, leather-bound bible. He learned to quote the passages that urged the listeners to make a joyful noise and celebrate life. He never claimed to be a minister, but if his dress and demeanor intimated such, he found no reason to deny it.

If requested, he could conduct a brief nondenominational service of a Sunday morning, after which he would bring out his baseball equipment and retire to the nearest meadow with the men and boys. Even the most pinched and pious farm women could find no fault with a hard-working pastor who regarded baseball as a sinless pastime for a sunny summer Sunday afternoon.

Occasionally, Sandor stumbled into a situation where a minister was clearly needed. He was known to pray with vigor over the terminally ill, preparing them for passage to the next world, easing that passage. When called upon he conducted funerals, baptisms, even an occasional marriage, though he loathed the intolerance of most Christians. ‘Christianity is the only army that shoots its own wounded,’ he said in one of his last letters to his sister, Evita.

As a boy he had heard or read that it matters not what qualifications one possesses, but only that one look the part, words that would have a profound effect on the many lives of Sandor Boatly. For instead of planting trees as a legacy, he planted the joy of baseball in several thousand hearts, and, as a seed grew into a sapling, then a tree, and eventually into a forest, so his own efforts multiplied over the years until baseball was everywhere in America, like the trees and the rain.

Sandor worked his way as far west as Wyoming, before heading south, touring Colorado, New Mexico and Texas, crossing several Southern states before finding himself in Florida – Miami to be specific.

Though he had never lived in a truly warm climate he always sensed deep in his bones that the natural state of the universe was endless summer, though he had only heard rumors of its existence. He had heard of places where the grass was eternally green, where snow was spoken of with nostalgia by people who had not endured it for years. But Miami, and Florida, that tropical green finger with the angelic aura of white sand, was so perfect, so magical, the possibilities of baseball so endless, that its mere existence almost caused Sandor to acknowledge the possibility of a God.

What he discovered, something that disappointed him to no end, was that in Florida he was not a pioneer, for baseball was well known, played in every park, school yard and vacant lot. Only in the furthest backwaters of the Everglades could he practice his calling, and then with only limited success, due to the lack of arable land.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.