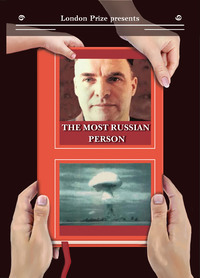

Czytaj książkę: «The Most Russian Person»

© V Shatakishvili, 2020

© International Union of Writers, 2020

Vladimir Shatakishvili began to write books when his beloved wife got seriously ill. He had to do something just to stay in this world. The longing and bitterness overshadowed the whole world when the blue eyes of Lyudmila closed forever, but the fourteen-year-old Sandro (Alex), with a desperate hope, was looking at Vladimir with the same blue eyes. He had to live! So, he wrote dozens of notebooks with confessions of “resurrected” toastmaster, whose good friends never ceased to invite him to feasts, where he said lovely words wishing them eternal health, love, happiness and wealth… Having found out about his diaries, the son persuaded his father to publish these stories, and soon his books came out: “The Casket of Colourful Contemporaries” (2004), “Ball Wanted” (2005), “The Most Russian Person” (2007), “Companion at the Feast” (2012), “How Well We Lived Badly” (2014).

Word of the editor

For every person, the ability to control oneself and one’s emotions is the primary, necessary duty. This is more than once emphasized by the author of the book, Vladimir Shatakishvili. He writes about what he knows personally, what he himself has experienced. That’s why he is so interesting. Reading his stories, novels, memoirs, you fall in love with his heroes: Russians, Georgians, Armenians, Ukrainians, Greeks, French, Germans, Americans, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Ossetians, British, Jews, Spaniards… And I really want to be among them (decent people), make toasts, enjoy life, be beautiful spiritually and physically, as they are. And mistakes, and mistakes? And who does not have them? Everybody does. As well the betrayal of loved ones, indifference of colleagues, buddies, and you want to howl like a wolf when you are left alone with your problems. Communication cleans the soul, enriches the person. Ill-wishers promised him and his friends defeat in life. And they’ve got a knockout. A living river, no matter what stones are in its path, must flow! Vladimir Shatakishvili stepped over the 60-year-old frontier, hasn't stumbled, fallen, and his heroes are alive: they create, raise children and grandchildren, overcome great difficulties with honor and are demanded by time and society.

After reading the book by Vladimir Shatakishvili, you understand, that the fate was generous to him, it presented tens, hundreds of friends around the world. Communicating with them is a priceless gift. Meeting everyone, he worries every time if others will be better after talking to him. Having read his stories about Shota Gabritchidze, Bitchiko Davlianidze, Ivan Medyanik, Andrey Gedikyants, Gennadiy Novakhov, Amiran Hurtsiya, Sergo Mgaloblishvili, Maysuradze, Vyacheslav Shulzhenko, Boris Arustamov, David Topuria, Gela Lobzhanidze, Boris Rosenfeld, there is a feeling that you are exchanging your thoughts and feelings with his characters.

In the first row, who Vladimir Shatakishvili describes, is the man of tremendous fate, a veteran of the nuclear industry, a strong-willed, demanding leader, Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik. The author had frank conversations with him for several years, not trying to declassify a highly secret industry – the production of atomic weapons, which he was involved in, but offered his collocutor a sort of know-how: to talk only about feasts in his eventful life, when meeting iconic figures of the 20th century. If we apply the Lermontov formula “the hero of our time” to him, then in the twentieth century, of course, it will be Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik. Without any misgivings (he gave a non-disclosure subscription) he spoke about the most prominent scientists: Kurchatov, Korolev, Marshals Budyonny, Zhukov, Voroshilov, Minister Slavsky, director of the “Mayak” plant Muzrukov. He remembered Beria, Kobulov, Shvernik… The man of legend is exactly about him! He did not live a year to his century.

Nikolay Pavlovich Lobzhanidze – a man of legend. Thanks to his incessant talent cafes, bars and restaurants of the level of civilized Europe appeared in Yessentuki and Kislovodsk. He defended, and, in fact, saved Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev during the struggle for power in the Kremlin. We read in the book: “What a wonderful and wise man was Lobzhanidze! A professional, kindhearted, friendly, hospitable, and, of course, decent – a worthy son of the Georgian people.” “And if everyone improves oneself, his home, his country, not looking for enemies from the outside, but was aware of his advantages and disadvantages, the society would have been perfect. Maybe there would have been no wars”, Vladimir Shatakishvili writes bitterly. “My father, Akakiy Mikhailovich, is the first victim of the war. Seriously wounded in a battle near Poltava, a percussion bullet hit the face, tore off his cheek and nose. While the war was going on, for several years he moved around hospitals, and even when the war was over, he was still lying on hospital beds for a long time, mouth breathing for a year and a half. He underwent twenty-eight plastic surgeries without anesthesia! What kind of courage and willpower you need to have in order to consciously go through such anguish!” Awesome pages, the best in the book.

The US Deputy Secretary of State arrived in Tbilisi. He was greeted according to high status: with honor and respect. After a fascinating tour of the city the solemn dinner was held. One of the invited Merab Bochorishvili, an artist, began to talk to the American in familiar way. Animation arose in the hall; the guests laughed and joked. Guys from the guard asked the artist to behave more modestly. To which Bochorishvili declared, “Everyone sitting at the Georgian table is equal, regardless of the positions and titles, only one person is listened to – tamada”. So toastmaster tries to explain to people, who drink, how to behave well at a feast, to listen to him, who is responsible for everyone. The person having been chosen as the tamada is the most competent and responsible, otherwise who will listen to him. He always knows when and to whom it is necessary to “hit the brakes”, to stop at the right moment, before he does any foolishness. “Not to let down human dignity of the one, who drank in your presence and under your table leadership, is one of the main tasks of an experienced toastmaster,” the writer concludes. And adds, “There is help to the state, too. Explanatory work with people is obligatory: cultural, respectful behavior of a guest at the table allows you to observe discipline, activate self-control, make you think about the consequences that await you round the corner”. It's hard not to agree.

Vladimir Shatakishvili is in good shape. Thanks to the sport he has been going in for since his school years, and this gives hope for long years and the continuation of our meetings with him. Kind, sympathetic, he attracts talented, extraordinary people, knows how to talk to them, to open up, to remember something significant in life and in the life of their friends, acquaintances. He has got followers: philologists Georgiy Lobzhanidze, Rafael Avedisov, Jorge Alfonso Moran.

He was born in the twentieth century, but as a writer in the twenty-first. I can safely say this because I was side by side with him, I have edited all his books. And he has written and published six in 15 years from 2004 to 2019: “The Casket of Colourful Contemporaries”, “Ball Wanted”, “The Most Russian Person”, “Companion at the Feast”, “How Well We Lived Badly” and “The Toastmaster's Confession”. They have their own lives, their readers, their fans. I dare think: cheerful persons, like his heroes.

Alexander IVANENKO,

Chief Editor

North Caucasian Publishing house MIL

Vladimir Shatakishvili

The Most Russian Person

Time makes a man.

Russian proverb

A STORY ABOUT A MAN FROM “MAYAK” – IN INTERVIEW, EPISODES, LYRICAL DIGRESSIONS

NORTH CAUCASIAN

MIL PUBLISHING HOUSE

PYATIGORSK / 2007

The share of a generation that had matured in the thirties of the last century had unprecedented ups and downs. They all passed through the heart of Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik. New cities are connected with his name: Ozersk in the Urals and Lermontov in the Caucasus. Whoever he was not in his life: a blacksmith, a tinker, a driver, a tractor driver, a tankman, a pilot, a battalion commander, and a prominent leader who carried out important government assignments. When many documents have been declassified today, it became known that I. N. Medyanik was involved in those who created the country's nuclear shield.

V. A. Shatakishvili. “The Most Russian Person.” Documentary story, 2007

North Caucasian publishing house MIL, 2007

Meet: Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik

Year of birth: 1912

Place of birth: the most Russian river – the Volga, more precisely, a small village with a very Russian name – Rodnikovka

Name: the most Russian in the world – Ivan

Height: 194

Weight: 110 (before retirement)

First sat behind the car wheel in 1927

Still drives it today, in 2008

Member of the CPSU – since 1935

Employment record – since 1925

It all started with cabbage

I first heard about it in the year of 1984. The father of my school friend Volodya Avetisov – Georgiy Alexandrovich – told us a curious story about the benefits of consuming cabbage. We went with a buddy to the Yessentuki Hotel buffet to have a snack, and there were only boiled eggs and fresh cabbage salad, and, of course, tea. At this small meal I was told the story I have remembered many years.

The essence of the story was the following. One distinguished person ate cabbage daily for many years: in the morning, at lunch and in the evening. He ate cabbage habitual for each: fresh, sauerkraut, pickled, stewed, stuffed cabbage, pies with the appropriate filling, in addition to the borsch, cabbage soup, etc. On the one hand, there is nothing surprising in gastronomic passions of a man to like popular and beloved by people vegetable, of course not, but cabbage saved his life long ago.

This conversation took place two years before the Chernobyl disaster, and the world still has not known the horrors suffered by our country. All the facts were urgently classified about previous similar accidents. People who had information or were affected by this accident gave a subscription not to disclose state secrets and this is serious. According to Georgiy Alexandrovitch we found out that his good friend Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik, in the early postwar years, worked as the head of a major undercover unit engaged in the production of atomic bombs. There were tens of thousands of people under his command, among which, besides, were volunteers, prisoners and even German prisoners of war. The trouble happened suddenly, many got almost fatal dose of radiation. People were tested daily, taken blood tests, but the results were disappointing. Frankly speaking, it should be noted that at that time nobody knew that this was the disease with possible fatal consequences.

One day a German prisoner of war came to the receiption to Ivan Nikiforovich and said he was well aware of the seriousness of the situation and being a medical doctor was willing to share with a known way of treatment by cabbage.

He said to let Chief try this method himself first, and, if blood tests improve, then this experiment can be applied on all affected. The Chief agreed and ate almost tons of cabbage in different forms for a few months. Soon he was invited to the lab and offered one more analysis because the previous had failed to conform to the established indicators. They did the second, third, 10th time… Everything spoke of a stable tendency towards improvement. And echelons with cabbage went to the Urals. Radiation receded.

Spring of 2003. I’m sitting in the office of the General Director of JSC “Gorjachevodsk” A. P. Sahtaridi. It was the time when the project for the construction of ice palaces was started in Mineralnye Vody. I and Alexander Petrovich were going to Moscow by evening flight for talks with Vice President of the Professional Hockey League of Russia V. T. Shalaev.

Before departure it was necessary to discuss and take some important organizational decisions. The secretary was asked not to let anyone come in the cabinet although there were a lot of people in the reception. Despite the warning she let in a tall old man decorated with orders and medals. I must say that the head office was located in the car service station No. 1, and the newcomer, familiar with the current owner of the cabinet, was introduced as its first director who had built it from scratch. The guest had been the friend of Pyotr Pavlovich, father of Alexander Sahtaridi, for many years. The veteran asked to help to repair his old Moskvich-2141. The foreman was invited and told to carry out a complete maintenance of the vehicle at the expense of the enterprise. Then tea with honey was brought, and the conversation about the problems of transport started.

I only joined the conversation when the guest said, that, by the way, he was going to be 91 in a month. I think you will agree that it is a considerable age for a driver. As my head was clogged with hockey and a possible solution, simple men's conversation seemed not to be interesting at all for me. But suddenly, I heard the name, which was in my head, Medyanik, plus his involvement in the testing of the first atomic bomb in the USSR. One should be complete ignorant (and I don’t consider myself to be such), so as not to realize that the very same man-legend was sitting in front of me, whose life was saved by cabbage. I had known this fact for two decades. Of course, I dreamed of meeting him, but I could not even assume that he was still alive and good (forgive me, Ivan Nikiforovich), and fate would give me a magnificent gift. Soon we became not only familiar, but friends.

I was very much excited and confessed to my new acquaintance that I knew about his miraculous healing. It turned out that not everything in the legend corresponded to reality: something had been changed taking into account the requirements of the post-war time, something was embellished, but in general this fact really took place in the biography of my hero. Printing of the book “Without guarantees of the century”, dedicated to the brilliant biography of Ivan Nikiforovich, written by a well-known in the Caucasus and a member of the Writers' Union of Russia and respected by me Alexander Fyodorovich Mosintsev, was being completed. After reading the book, I was convinced that there were still a lot of facts left for me. And I also thought of writing a book about Medyanik. His fate is amazing. Awesome. Fiery fate! So I will try to interview this Fate. The Fate of a wonderful person.

On June 2, 2006, Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik turned 94, and this little story is about him. I hope it will be my gift for his jubilee, the 95th anniversary, in appreciation for what he had done for millions of people.

I'm on friendly terms with my memory…

WHEN Ivan Nikiforovich goes through the memory of past days and years, it takes me aback. Top secret ideas, classified towns, objects, names in his stories acquire the coloring of such frank commonness, the taste of the ordinary servitude that at the beginning of our acquaintance (I confess!), somewhere deep down doubt arises if it was in reality. Has his memory changed? Isn’t there a natural desire to attach your name to the significant and fateful events of the Fatherland? After all, human vanity is a mysterious and incomprehensible category.

No, no and no! His memory didn’t betray him, he was, in fact, a witness and direct participant of those bygone events. And he does not boast, does not expect the thunder of copper pipes of glory – this tall, grayhaired man with a piercing glance of intelligent eyes and a faint grin, that seems to forgive my disbelief, speaks calmly and confidently.

Yes, he is not a nuclear physicist, not a professor, not a doctor of science. He did not take part in “capturing” the evasive neutrino, did not invent the electron brain, did not split the atom, did not “weigh” the star from Andromeda or Cassiopea's, did not beat his head against the wall seeking the right solution in clever projects.

He introduced himself as an experienced motorist, builder, transport worker. He has got a lot more professions that he had mastered, complying to the most severe life circumstances. Later I will tell about it, too.

Now, at ninety-five, he continues to drive. He himself drives. The driver's license of the new sample is valid until 2009. The traffic police GAI (I use the old, familiar to the ear abbreviation of the team of law enforcement officers) do not stop him to verify the identification or for violation of the medical, precisely, age restrictions. Yes, they know, they know our grand-dad, they know Ivan Nikiforovich in Stavropol region, and Mineralnye Vody, in Moscow, in the Urals, he is remembered in all classified “Chelyabinsk” ones, and on the once super classified “Mayak”.

He is neither a professor, nor a doctor of science, nor an academician. But he has the title “Veteran of Nuclear Energy and Industry”. And he is proud of it by right. He was directly involved in the preparation of the testing of the first Soviet atomic bomb which our brilliant nuclear scientists, the finest scientific minds in the world, created “to fear the enemies and world imperialism”.

The first received radioactive plutonium – this monstrous deadly “stuffing” for the first Soviet atomic bomb – was delivered to its destination in February 1949 by Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik. It was dangerous. It was extremely dangerous! Both for the driver himself, and for his obligatory escort from the department of Lavrentiy Beria – colonel N. M. Ryzhov, and for classified cities, not-marked on any map, in which the bomb was grown from the idea to the real incarnation. Dangerous eventually for hundreds of thousands of people, for the earth, and the sky, and for the whole of Urals with its innumerable natural resources.

Winter, frozen roads, hard and remote, where every unexpected bump could turn a disaster – everything is remembered by Ivan Nikiforovich as if he had just brushed off cold sweat from the forehead from tension, natural excitement, and involuntary fear for a possible unforeseen error.

The car with a deadly cargo was sent in its dangerous trip by a well-known physicist Yuliy Borisovich Khariton, having “blessed” it in his “scientist way”.

Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov met it at the destination point, openly pleased. He shook Ivan Nikiforovich Medyanik's hand “like a nuclear scientist to a nuclear scientist” and smiled slyly.

Everything worked out. Plutonium, without which the bomb was just an empty shell, was delivered to the laboratory. The last months came before the test. The rest, just lazy or too young, do not know: On August 29, 1949, the first Soviet atomic bomb was tested at a nuclear test site near Semipalatinsk.

The USSR nuclear shield – as opposed to the United States – declared itself in full voice!

“And do you yourself, Ivan Nikiforovich, remember those famous scientists with whom you had to communicate or at least see on the famous “Mayak” (Chelyabinsk-40)?”

“Will you give me a piece of paper,” Ivan Nikiforovich gets excited, “I will write the names of those you probably have no idea about, no offense.”

And he took the pen.

I here give names and surnames written by Ivan Nikiforovich. This is an incomplete list of people, involved in the production of the atomic bomb at “Mayak”:

I. V. Kurchatov

A. N. Nesmeyanov

L. P. Beria

L. D. Landau

Y. B. Khariton

P. L. Kapitsa

B. L. Vannikov

I. E. Tamm

A. P. Alexandrov

L. V. Kantorovich

A. D. Sakharov

A. M. Prokhorov

S. P. Korolev

N. G. Basov

B. G. Muzrukov

A. F. Joffe

A. I. Alikhanov

M. G. Pervukhin

A. S. Nikiforov

P. A. Cherenkov

N. I. Bochvar

V. G. Khlopin

N. A. Dollezhal

V. S. Emelyanov

I. M. Frank

A. I. Alikhanyan

N. N. Semyonov

S. L. Sobolev

V. I. Alferov

I. F. Tevosyan

M. M. Tsarevsky

I. E. Starik

V. S. Fursov

I. I. Gurevich

M. V. Keldysh

I. Y. Pomeranchuk

D. F. Ustinov

N. L. Dukhov

A. P. Zavenyagin

E. I. Zababakhin

G. N. Flerov

K. I. Shchelkin

I. K. Kikoin

V. I. Vexler

V. A. Malyshev

A. K. Kruglov

E. P. Slavsky

N. V. Melnikov

Y. B. Zeldovich

A. P. Vinogradov

“Here you go! And this, of course, is not all. The list can be continued. But you, Volodya, aren’t going to compile a personalized encyclopedia of nuclear scientists?” Ivan Nikiforovich smiled. “The first one I put is Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov. He was the chief scientific officer of the atomic project. Unusual man. The fire. Himself like a nuclear reactor. No wonder his nickname was “atomic boiler” – for the incredible efficiency. The man was just boiling! Everyone loved him. Respected by men, loved by women. They gave a gently nickname – Prince Igor, and his subordinates addressed in their own way – Beard. He wore a special beard, of unusual shape, cut off at the end “under the line”, with a gray at the chin. The forehead is tall and strong, and eyes sparkle cheerfully. Cheerful when not busy. Well, what about the “man”… I got excited. Although I said in a good way. On the contrary, he was a nobleman,” Ivan Nikiforovich laughs. “And, in general, a real man! Russian hero. It’s a pity he passed away early, well, what is this age – 57? He did not live up only a year before the flight of Gagarin, died in 1960 in February after the second stroke.”

“I know that you and Kurchatov often met and talked. How was it?”

“I remember the first meeting. I took up my duties at the very beginning of 1948. Somewhere in March Kurchatov appeared at the construction site. He was informed about a new head of the motor vehicle fleet at the plant. Besides, one of the drivers (there were several of them) spoke well of the “new broomstick”. They say I began to put things in order from the very first day. The academician conveyed through the head of the personal security Vasiliy Vasilyevich Kulikov for me to show up. I came at the appointed time and was immediately received. A young, tall, handsome man, he impressed me. As it should be in such cases, I wanted to introduce myself, tell about myself, but Kurchatov decidedly stopped me, “I know everything about you. I had a meeting with the secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Mikhail Andreevich Suslov. He said that he had sent me two reliable guys he as a member of the Military Council of the North Caucasus had known since the war and vouched for them. He said about Trovchenko, the representative of the Council of the Ministers, and you, Ivan Nikiforovich. Suslov also added that they are military people, they will bring order.” Of course, I was flattered that I was presented to the world-famous scientist on the positive side and really wanted to justify his trust. Then we switched to urgent matters. A serious and important conversation took place. The main production – the creation of a bomb – consumed all the finances, and we understood that. But the transport was desperately needed, as well as good reliable roads. It’s a shame – impassable mud, even in sunny weather, not to mention especially in rain or sleet.

After all, when a new home is being built, and even more a city, they can’t avoid the thing that the earth resists, soaks to a slurry, sticks to shoes, clothes. To go two or three times, you spend a lot of time for washing shoes. And Igor Vasilyevich, despite being the “master” and “Prince Igor”, loved to go in the galoshes (rubbers). It was comfortable and the shoes were clean! Looking at him, soon everyone in “Mayak” put on galoshes. But it was not an option. I said that in Germany, before construction, they, first of all, build roads, asphalt them so that building materials could arrive on time, the garbage is taken out, and people are comfortable. This is a standard of work! And are we worse? Though the year we talked about was hard – the 48th, we didn’t still recover from the war, and the anger against the Germans was still hot – they were enemies after all. But I believe that it is possible to learn reasonable economic management from the enemy.

Igor Vasilyevich looked at me sharply (with understanding, it means) and asked for some patience. He said he knew how important transport was in our business. “In every sense, you are our “ambulance”. We are sure to help, I promise,” he said and kept his word. He always said simply, with jokes, which, of course, were relevant. He was always the center of attention. When we went fishing, he was busy with our kids and also with jokes. Through a joke, the boys were crammed with serious things about science, serious study, for example. That way he made his son Zhenka fall in love with these same sciences, so that when he grew up, he became submarine designer. He is now seventy-two years old, Honored Submariner of Russia, lives in Severodvinsk. Here is what else Igor Vasilyevich asked me about during that first meeting: “You, Ivan Nikiforovich, should be as military strict with subordinates. People from all over the country will soon come here, you need to continuously deliver them to the plant – from Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk. In addition, a huge amount of cargo will also go and they should not suffer. This is a responsible matter, but I hope you can handle it.”

“Sure I will cope, Igor Vasilyevich!”

Academician rose from the table, came close and firmly shook my hand. Our eyes met, he carefully began to examine me, from close range. We turned out to be the same height and it is when I was almost two meters tall! On “Mayak” people of this height are rare.

“And now about the main thing. All the country's science, famous academics, started moving to us. They need to be placed in three cottages specially built for them,” Kurchatov paused. “But remember that the academicians are the same children, they wear hats in summer and winter. Please meet each in person, do not reassign to anyone. And change hats to caps!”

From this day on, I met and placed “domestic science” personally. People were different: more silent, thoughtful, and there were capricious, and such as Yuliy Borisovich Khariton – cheerful, good-humoured. I went hunting and fishing with them. I got the most important thing: every academician was a secret person, the country would learn many of their names later after their discoveries, and in the case of Sergey Pavlovich Korolev only after his death.

For especially important guests I warmed two cars in stock. I made out sheepskin coats, felt boots, fur hats and, whatever happens, a few bottles of Armenian brandy.

Such a case soon came up. Boris Glebovich Muzrukov, director of the plant, calls me and says, “There hasn’t been any news from the people meeting Korolev for a long time. You are at control”. It was almost the only time when someone else instead of me went to meet, and no one knew who Korolev was. I called the driver of one of the already equipped cars, and we rushed. Somewhere after ten kilometers we saw a car that had slid to the side of the road. The driver was busy under the hood, and two passengers and a welcomer were standing nearby. In order not to waste time, I gave the command to the drivers to take the stalled car in tow, and made the guests put on sheepskin coats, hats and boots, practically making them change clothes in the cold. Then I poured cognac into glasses, offered cheese, sausages, something else and soon brought the latecomers to the place. I ran to Muzrukov, reported that everything was in order (it was night, and our cottages were nearby), but he laughed, “Korolev has already called, said that some huge “chief”, as the chauffeurs call him, arrived and forced him change clothes and even made him drink brandy.” After that, I met Sergey Pavlovich more than once. He was a charming and modest person. Although neither a hunter nor a fisherman, he never refused to go to the country.”

“Ivan Nikiforovich! My interview with you has stretched out for long four years. An entire story was written, handed over to the editor, and on January 12, 2007, there came the centenary of Sergey Pavlovich Korolev. Let's go back and talk about what you have remembered from your meetings with him.”

“There were several such meetings. Where do we start?”

“Tell everything that you remember, and then put the episodes in chronological order.”

“To begin with, over the years of my work at “Mayak”, I met Sergey Pavlovich every time, except for the episode already described. His arrivals were associated with the development and supply of fuel for future space missions. Train sets of tanks went constantly from us to Baikonur. He made closest friendly relations, I would even say, with Slavsky, Muzrukov, Kurchatov.”

“Did close communication with him happen after your eight-year work at “Mayak”?”

“Yes, the first such meeting took place in 1957. By that time I had moved to Mineralnye Vody and worked in Lermontov as the head of the motor transport at a classified unit. Once in the director’s receiption I was informed that they had called from Kislovodsk and asked to get in touch. It turned out that on Korolev’s instructions, his assistant was looking for me and sent me an invitation to come to Ordzhonikidze Sanatorium. After work I started my new Volga and headed for Kislovodsk. The meeting turned out to be warm and friendly. While walking in the park for a couple of hours, we remembered mutual friends, acquaintances, some episodes from our life in the Urals. We planned a trip to Elbrus region. Vladimir Semyonovich Khomutov, chief medical officer, was the initiator of it. I took over the organization of shashlyk, pickled meat and picked up a set of stainless steel skewers brought from the Urals. All other problems were laid on the management of the sanatorium. The next morning we met on the highway Pyatigorsk – Nalchik, and three cars drove into the mountains. Elbrus region today still remains one of the largest centers of mountaineering and skiing in the country.