Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Northanger Abbey»

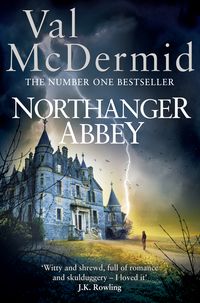

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Copyright © Val McDermid 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photographs © Sandra Cunningham/Arcangel Images (grass); Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Val McDermid asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN 9780007504299

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007504282

Version 2014-08-09

Dedication

To Joanna Steven, constant reader, constant friend, who is indirectly responsible for introducing me to the delights of the Piddle Valley.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

In conversation with Val McDermid

Val McDermid on Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Val McDermid

About the Publisher

1

It was a source of constant disappointment to Catherine Morland that her life did not more closely resemble her books. Or rather, that the books in which she found its likeness were so unexciting. Plenty of novels were set in small country villages and towns like the Dorset hamlet where she lived. Admittedly, they didn’t all have such ridiculous names as the ones in the Piddle Valley where her father’s group of parishes was centred. It would have been hard to make credible a romantic fiction set in Farleigh Piddle, Middle Piddle, Nether Piddle and Piddle Dummer. But in every other respect, books about country life were just like home, only duller, if that were possible. The books that made her heart beat faster were never set anywhere she had ever been.

Cat, as she preferred to be known – on the basis that nobody should emerge from their teens with the name their parents had chosen – had been disappointed by her life for as long as she could remember. Her family were, in her eyes, deeply average and desperately dull. Her father ministered to five Church of England parishes with good-natured charm and a gift for sermons that were not quite entertaining but not quite boring either. Her mother had given up primary school teaching for the unpaid job of vicar’s wife, which she accomplished with few complaints and enough imagination to leaven its potential for dreariness. If she’d had an annual performance review, it would have read, ‘Annie Morland is a cheerful and hard-working team member who treats problems as challenges. Her hens are, for the third year in a row, the best layers in the Piddle Valley.’ Her parents seldom argued, never fought. Between the two of them, there wasn’t a single dark secret.

Even their home was a disappointment to Cat. Ten years before her birth, the Church of England had sold the draughty Victorian Gothic vicarage to an advertising executive from London and built a modern executive home with all the aesthetic appeal of a cornflakes packet for the vicar and his family. In spite of its relatively recent construction it had developed just as many draughts as its predecessor with none of the charm. It was not a backdrop that fuelled her imagination one whit.

Cat’s tomboy childhood had been a product of her desire to be the heroine of her own adventure. The stories she had first heard and later read for herself had fired her imagination and given her a fantasy world to play with. Her delight at having siblings – older brother James and younger sisters Sarah and Emily – was largely due to the roles she was able to assign them in her elaborate scenarios of battling monsters, rescuing the beleaguered and conquering distant planets.

For most children blessed – or cursed – with so vivid an imagination, the natural outlet is school. But Annie Morland had experienced what she called ‘the education factories’ at first hand and it had left her with a firm conviction that her children would best thrive under her own instruction. And so Cat and her siblings were denied exposure to a classroom and playground society that might have subjected them to life’s harsher realities. No one ever stole their dinner money or humiliated them in front of a roomful of their peers. Instead, they came under the constant scrutiny of a mother and father who wanted only the best for them.

James, blessed with natural wit and intelligence, would have succeeded whatever educational system had been imposed on him. And Cat, who cared more for narrative than knowledge, would probably have done no better wherever she’d been taught. They would certainly have become wiser in the ways of the world if they’d escaped their mother’s apron strings, but had that been the case, their story would be too commonplace to hold much interest for an ardent reader.

Their only significant contact with their peers happened in the small park that had been created from a water meadow donated to the village on the occasion of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. The gift had been made by an international agribusiness keen to catch the eye of the Prince of Wales; and besides, the field had no significant agricultural potential since it lay within an oxbow of the Piddle and so could not be aggregated into one of the prairies so beloved by commercial farming. The park contained a football pitch, a tennis court, an adventure playground and, thanks to an American couple who had moved into the Old Schoolhouse, a rudimentary baseball diamond. Whenever school was out, the field acted as a child magnet. Little was formally organised, but there were always pick-up games of one sort or another into which the junior Morlands were readily absorbed. Cat particularly enjoyed any sort of ball game that included rolling or sliding in the dirt.

Cat progressed from tomboy to teenager without showing any academic or sporting distinction whatsoever. Her enthusiasm seldom lasted long enough to produce any solid results. Often her mother despaired of ever managing to shoehorn a French irregular verb or a simple algebraic equation into her daughter’s brain. After a nature walk, Cat would rather sit round the fire telling ghost stories than discussing the flora and fauna they’d seen in the woods and fields. She made notes when her mother insisted, then promptly mislaid them. Whenever she could drag their lesson off track, she did. In a history lesson, Annie would suddenly realise that instead of learning about Tudor foreign policy, her daughter was making the case for Henry VIII’s much-married state.

Faced with constant failure, Annie tried to find an explanation. Perhaps Cat was one of those individuals whose right brain dominated, making them creative, musical and imaginative. ‘Does that also include being utterly incapable of focusing on anything for more than two minutes at a time?’ her husband asked with mild exasperation when she outlined this theory to him one night as they retired to bed. ‘Who knows if she’s musical or creative? She says she loves music but she never practises the piano. She says she loves stories but she never finishes any of the ones she starts writing. She can’t be bothered earning pocket money because there’s nothing she wants to spend it on. All she wants are novels, and she can get as many of those as she wants from our bookshelves and the library bus. Honestly, Annie, as far as I can tell, she inhabits an entirely separate universe from the rest of us. She’s a completely dozy article.’

‘And what kind of future is she going to have?’ Annie tried not to admit pessimism into any area of her life, but where her eldest daughter was concerned, it was hard not to let it sneak in through the slightest crack in her defences.

‘One that requires no qualifications other than a good heart,’ Richard Morland said, rolling over and punching his pillow into submission. ‘Look how good she is with the little ones. Catherine will be fine,’ he added with more confidence than his wife thought he had any right to. That, she supposed, was where your faith came in.

Cat meanwhile was sleeping the sleep of the unconcerned, lost in happy dreams of adventure and romance. The details of her future never disturbed her interior life. She was serenely convinced that she would be a heroine. In her mind, all her life had been a preparation for that role. That wasn’t to say there wouldn’t be obstacles. Anybody who knew anything about adventures knew there would be stumbling blocks aplenty along the way to true love and happiness. Their families would be at war or her beloved would turn out to be a vampire or they would be separated by an ocean or an apparently terminal illness. But she would triumph and conquer every barrier to a satisfactory ending.

The only problem was how these exploits were going to get started. Years of ranging through the back gardens and living rooms of Piddle Wallop under cover of childish games and pastimes had convinced her she knew all there was to know of her neighbours. Of course, she was entirely mistaken in this assumption, but her blissful conviction was unlikely to be overturned while she paid more attention to the inside of her head than the secrets of those who surrounded her. As far as Cat was concerned, she knew nobody who was likely to provoke any sort of adventure. If she was going to embark on an escapade, she would first have to escape the narrow confines of the Piddle Valley. And she couldn’t see how she was ever going to manage that.

She was on the brink of despair when the impossible happened. In one brief moment, her prospects were transformed. Like Cinderella, it appeared that Cat was going to have her chance after all. If not at Prince Charming, then at least at the twenty-first century equivalent of the ball.

Their neighbours, Susie and Andrew Allen, were the culture vultures of the Piddle Valley. Andrew was the shrewdest of angels. His eye for theatrical gold had led him to a tidy fortune through investment in the West End commercial stage. He had no particular love of the performing arts but he possessed the knack of knowing what would please the popular taste.

For years, he had spent the summer in Edinburgh for the Festival, cramming every day to capacity with Fringe performances and Book Festival events that might conceivably inspire a musical. But a minor heart attack had felled him in the spring and Susie had insisted that this year must be different. This year, she would accompany him and he would be permitted to attend a maximum of two shows a day. ‘Because there are plenty of ways to have a good time in Edinburgh without having to sit through a one-woman show of King Lear, or a comedian doing Jane Austen’s Men,’ she’d said to Annie Morland. For although Susie Allen had herself been an actress, she had a surprisingly low threshold of attention when it came to attending the theatre.

But in order for Susie to enjoy those good times, she needed a companion for the awkward occasions when Andrew insisted on seeing a show whose description alone made her shudder. She had a very clear idea of the style of companionship she wanted. Someone whose youth would reflect positively on her; someone whose unformed opinions would have insufficient grounding to contradict hers; and someone who would attract interesting company without ever dominating it.

This was not how Susie expressed the matter either to herself or to the Morlands. And thus Cat was to be found one morning at the beginning of August packing her bag for a month in the Athens of the North, excited and delighted in equal measure.

2

No golden coach with white horses was laid on to transport Cat to Edinburgh. Instead, she faced the prospect of spending eight hours confined in the back seat of Susie and Andrew Allen’s Volvo estate. But Cat was convinced she’d be fine, even though she’d never been further than Bristol in the Morlands’ ancient people carrier. In the car, she’d be able to sleep and to read, those two essential components of her life.

There was no elaborate leave-taking of her parents. It was as if they had exhausted their potential for making a fuss of departing children when James had left four years before for Oxford. Cat had to admit to a twinge of disappointment at the apparent indifference of her family to her imminent absence. True, her mother gave her a smothering hug but it was followed by a brusque reminder to take her vitamins every morning. ‘And don’t forget you’re on a budget. Don’t blow the lot in the first few days. What you’ve got has to last you a month. You can’t turn to the bank of mum and dad if you run out of cash,’ she’d added sternly. Annie displayed not a sign of concern about what dangers might lurk on the streets of Edinburgh, in spite of having read the crime novels of both Ian Rankin and Kate Atkinson.

Hoping for something a little more affectionate or apprehensive, Cat turned to her sisters. ‘I’ll text you when I get there,’ she said. ‘And I’ll be on Facebook and Twitter big time.’

Sarah shrugged, either from envy or indifference. ‘Whatever,’ she mumbled.

‘I’ll post photos too.’

Emily looked away, apparently fascinated by the contrail left by a fighter jet. ‘If you like.’

Cat gave her father a look of appeal, hoping he at least would display some sign of dreading her departure. He slung a companionable arm round her shoulders and drew her away from the driveway towards the ramshackle garage where he indulged his woodworking hobby. ‘I’ve got a little something for you,’ he said.

Fearing another of his wooden trinket boxes, Cat let herself be led out of the sight of her mother and sisters. Instead, her father dug into the pocket of his jeans and produced a pair of crumpled twenty-pound notes. ‘Here’s a little extra spends for you.’ He put the money in her palm and folded her fingers over it.

‘Have you been robbing the collection plate?’ she teased him.

‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘There would have been more but the congregation’s been down this month. Listen, Cat. This is a great opportunity for you to see a bit of the world outside your window. Make the most of it.’

She threw her arms round his neck and kissed him. ‘Thanks, Dad. You always get it. This is the start of an amazing adventure. All these years, I’ve been reading about exciting exploits and wild escapades, and now I’m actually going to have one of my own.’

Richard’s smile held a touch of sadness. ‘I remember reading Swallows and Amazons and the Famous Five books and thinking that was how my life was going to be. But it didn’t turn out like that, Cat. Don’t be disappointed if your trip to Edinburgh doesn’t play out like a Harry Potter story.’

Cat snorted. ‘Harry Potter? Even little kids don’t believe Harry Potter’s for real. You can’t long for something you know is totally fantasy. It’s got to feel real before you can believe it could happen to you.’

Her father rumpled her long curly hair. ‘You’re talking to the wrong person. I believe in the Bible, remember?’

‘Yeah, but you’re not one of those crazies who think the Old Testament is history. What I mean is, all that magic and sorcery – nobody could believe that. But when I read about vampires, it could be true. It could be the way things are beneath the surface. Everything fits. It makes sense in a way that Quidditch and silly spells don’t.’

Richard laughed. ‘Well, I hope you can have an adventure in Edinburgh without being bitten by a vampire.’

Cat rolled her eyes. ‘Such a cliché, Dad. That’s so not what the undead are all about.’

Before he could respond, they were interrupted by a car horn. ‘Your carriage awaits,’ Richard said, gently pushing her out of the garage ahead of him.

The journey north was uneventful. In deference to Cat’s taste in literature, Susie had downloaded an abridged audio book of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. For Cat, schooled only in contemporary vampire romance, it was a curious and unsettling experience. It reminded her of the first time she’d tasted an olive. It was unlike everything that had crossed her palate before; strange and not quite pleasant, yet gilded with the promise of sophistication. This was what she would like when she knew enough of the world, it seemed to say. It was a guarantee that was more than enough to keep her focused on the conflict between the Transylvanian count and Professor Van Helsing.

The book ended and Cat drifted into consciousness of the outside world just as they reached the outskirts of the city centre. She squirmed out of her slouch on the back seat and eagerly scanned the neighbourhood, taking in the imposing symmetry of the grey stone buildings that lined the streets, interspersed with orderly tree-lined gardens enclosed by spiked railings. Although the light was barely fading into dusk, in her imagination it was a dark and foggy evening, when this would become a thrillingly ominous landscape. She had come to Edinburgh to be excited, and even at first sight, the city was living up to her expectations.

Mr Allen liked to live well, and he always took comfortable lodgings for his August pilgrimage. This year, he’d rented a three-bedroomed flat towards the West End of Queen Street which came with that contemporary Edinburgh equivalent of the Holy Grail – a parking permit. By the time they’d found a parking space that matched it, then lugged their bags up several flights of stairs, none of them had appetite or energy for anything more than a good night’s sleep.

Cat’s room was the smallest of the three bedrooms, but she didn’t care. It was painted in shades of yellow and lemon and there was plenty of room for a single bed, a dressing table, a wardrobe and a generous armchair that was perfect for curling up and reading. Best of all, it looked out over Queen Street Gardens. Cat had no difficulty in ignoring the constant traffic below and enjoying the broad canopy of trees. Now twilight had taken hold – and to her astonishment, it was already almost eleven o’clock, when it would be properly dark in Dorset – she could see bats flitting among the leaves. She gave a little shiver of pleasure before she closed the curtains and slipped into sleep.

Breakfast with the Allens was an even more casual affair than at the Morlands. When Cat emerged from the shower, she found Mr Allen in his dressing gown reading the Independent by the window, a cup of coffee at his elbow. He glanced up and said, ‘The supermarket delivery came. There’s fruit and juice and bacon and eggs in the fridge. Croissants in the bread bin and cereals in the cupboard. Help yourself to whatever you fancy.’

Spoiled for choice, Cat poured a glass of mango juice while she considered her options. ‘Is Susie still sleeping?’ she asked.

Mr Allen grunted. ‘Probably.’ He made a performance of closing his newspaper and draining his cup. ‘I’ve got a ticket for a show at half past ten at the Pleasance. A sketch comedy group from Birmingham doing a musical version of Middlemarch.’

‘That doesn’t sound very likely.’

He stood up and stretched. ‘And that, my dear Cat, is precisely why it might just work.’

Cat realised she still had a lot to learn about contemporary theatre. With luck, she’d know much more by the end of her four weeks in Edinburgh. ‘Are we coming with you?’

He chuckled. ‘God, no. Susie won’t venture anywhere near a cultural event until she’s kitted herself out in this season’s wardrobe. You two are destined for the shops this morning. I hope you’re feeling strong.’

At the time, she’d thought he was exaggerating, as she knew men are inclined to do on the subject of women and shopping. But by the fifth shop, the fifth pile of clothes, the fifth changing room, Cat was beginning to feel amazement at Mr Allen’s level of tolerance. Admittedly, she’d had little opportunity to observe married life at close quarters, apart from that of her parents. But although she didn’t like herself for the thought, Cat reckoned she had somehow previously missed the realisation that Susie Allen was the most empty-headed woman she’d ever spent time with. What was bewildering about this discovery was that Mr Allen was definitely neither empty-headed nor obsessed with how he looked. It was puzzling. All they seemed to share was curiosity. But while Mr Allen’s curiosity was aimed at finding new wonders to bring to the public’s attention, Susie Allen seemed interested only in spotting famous faces among the crowds that thronged the shops and the streets of Edinburgh.

‘Isn’t that the little Scottish woman who’s always on the News Quiz? Oh, and surely that’s Margaret Atwood over there, trying on hats? Oh look, it’s that rugby player with the big thighs.’ Such was the level of Susie’s discourse.

Her one saving grace, at least to a teenager, was her generosity. While she lavished a new wardrobe on herself, Susie was not slow to treat Cat to similar delights. Cat was not by nature greedy, but there was never much to spare in the Morland family budget for the vanity of fashion over practicality. Although Cat knew it was generosity enough to bring her on this trip and that her parents would disapprove of her accepting what they’d regard as unnecessary charity, she couldn’t help but be seduced by the stylish trifles Susie thought her due. Even so, by mid-afternoon, Cat was weary of retail therapy and longing to plunge into some cultural life.

Her prayers were answered when they returned to the flat to find Mr Allen sitting by the window with a cup of tea and his iPad. ‘I have tickets for you both for a comedy show this evening at the Assembly Rooms,’ he announced without stirring. ‘I’ve been invited to a whisky tasting, so I’ll meet you in the bar after the show.’

Cat retreated to her room, where she spread her new clothes on the bed and photographed each item with her phone. She posted her favourite shot – a camisole cunningly dyed in gradations of colour from fuchsia to pearly pink – on her Facebook page then sent the others to her sisters. She texted her parents to say she’d spent the day walking around with Susie and they’d be going out to see a show in the evening. Instinctively, she knew what not to tell her parents. Sarah and Emily wouldn’t give her away. Not because they were intent on keeping her confidences, but rather because their annoyance at what they were missing out on would manifest itself in blaming their parents.

The pavement under the triple-arched portico of the Assembly Rooms was busy with people milling around, eyes darting all over the place, eager to spot acquaintances or those they would like to become acquainted with. Posters plastered every surface, over-excited fonts trumpeting the attractions within. Everything clamoured for Cat’s attention and she clung nervously to Susie’s arm as they pushed through the crowds to get inside.

The scrum of people seemed to grow thicker the further they penetrated the building. Mr Allen had spoken of the grace and elegance of the interior, explaining how it had been restored to its eighteenth-century glory. ‘They’ve kept the perfect proportions and returned it to its original style of decoration, right down to the chandeliers and the gold leaf on the ceiling roses,’ he’d told them over their early dinner. Cat had been eager to see it for herself, but it was too crowded to form any sense of how it looked. In between the heads and the hoardings she could catch odd glimpses here and there, but it formed a bewildering kaleidoscope of images. The sole impression she had was of hundreds of people determined to see and be seen on their way to and from an assortment of performances.

‘I know where we’re going.’ Susie had to raise her voice to be heard in the throng. She half-led, half-dragged Cat through the crowd until they finally reached their destination. Susie handed over their tickets and they were admitted to the auditorium.

This was not Cat’s initiation into live performance. She’d regularly attended performances in the village hall and even, occasionally, at the Arts Centre in Dorchester. She knew what to expect. Rows of seats, a soft mumble of conversation, a curtained proscenium arch.

Instead, she was thrust into a hot humid mass of bodies that filled the space around a small raised dais at one end of the packed room. Through the gloom, she could see some chairs, but they were all taken. What remained was standing room only. Standing room so tightly packed that Cat was convinced if she passed out, nobody would know until they all began to file out and she crumpled to the floor.

‘It’s a bit hot,’ she protested.

‘You won’t notice when the show begins,’ Susie assured her.

Because Susie had taken so long to get ready, they were only just in time. A skinny young man with a jack-in-the-box spring in his step bounced on to the stage, his hair a wild shock of blond and blue that matched his T-shirt. He dived straight in with a barbed attack on his arrival in Edinburgh, his West Midlands delivery so fast and so heavily accented that Cat could barely make out one line in three.

The audience seemed to fare better, following the performance well enough to cheer, laugh and heckle in equal measure. It was a novel experience for Cat, and in spite of her discomfort, she found herself caught up in the atmosphere, clapping and laughing regardless of whether she’d got a particular joke.

Eventually the show came to an end, with whoops and cheers signalling that it had been more of a success than not. The one good thing about being so far back was that they were able to make a relatively quick getaway. It was almost dizzying to emerge into the relative airiness of the foyer after the closeness of the event. ‘The bar,’ Susie said, immediately dragging her away from the direction of the street and deeper into the bowels of the building. ‘I’m gagging for a drink.’

The bar was no less crowded. People stood three deep waiting to be served. Susie groaned and glanced at her watch. ‘Andrew will be here any minute; he can do the donkey work for us. Come on, let’s find a seat, my feet are killing me.’ Cat wasn’t surprised. Even a teenager would have had more sense than to go out for the evening in the ridiculous shoes Susie had bought that morning.

Finding a seat didn’t seem a likely prospect to Cat, but Susie was undaunted by the crowds. She spied a table occupied by a group of young people who were clearly together, bunched around wine bottles and glasses. Susie marched straight up to the table and plonked herself on the end of the banquette. ‘Squeeze up, darlings,’ she said, waving her hands in a shooing motion.

Despite their anarchic appearance, this was evidently a group of nicely brought-up students. They obediently squashed closer together, creating just enough space for Susie and a sliver of seat for Cat. But politeness didn’t extend to including the pair in their conversation. Cat felt invisible and unattractive. All at once it dawned on her that she had never been in a crowded place where she didn’t know most of the other people present. It was simultaneously thrilling and unnerving. The potential for romance or danger was all around her; it was time to embrace the unfamiliar, not shrink from it.

She turned to share her insight with Susie, who was scouring the room with a pout on her face. ‘Unbelievable. I emailed and Facebooked at least a dozen of my best friends to say we’d be here tonight and there’s not a single one of them to be seen. I wanted you to meet the Elliots, they’ve got a son around your age. And the Wintersons, their twin girls must be off to university at the end of the summer. But no. Not a soul in sight.’

Cat felt the bubble of excitement burst within her, pricked by Susie’s discontent. But before she could say anything, Mr Allen appeared, pushing his way through the press of bodies. ‘This is impossible,’ he said, breathing a cloud of whisky fumes over them both. ‘There’s no pleasure in this. Let’s just walk home and have a drink there.’

Darmowy fragment się skończył.