Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «A Darker Domain»

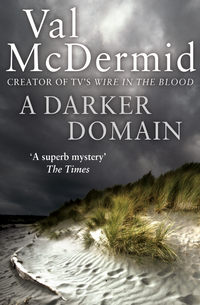

VAL McDERMID

A

Darker

Domain

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of Meg and Tom McCall, my maternal grandparents. They showed me love, they taught me about community, and they never forgot the shame of standing in line at a soup kitchen to feed their bairns. Thanks to them, I grew up loving the sea, the woods and the work of Agatha Christie. No small debt.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Tuesday 19th June 2007; Edinburgh

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Thursday 21st June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Monday 25th June 2007; Edinburgh

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

Thursday 28th June 2007; Edinburgh

Monday 18th June 2007; Campora, Tuscany, Italy.

Thursday 28th June 2007; Edinburgh

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Friday 14th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Friday 14th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Saturday 15th December 1984; Newton of Wemyss

Thursday 28th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Glenrothes

Rotheswell Castle

Wednesday 13th December 1978; Rotheswell Castle

Thursday 28th June 2007; Rotheswell Castle

Glenrothes

Kirkcaldy

Sunday 2nd December 1984; Wemyss Woods

Thursday 28th June 2007; Kirkcaldy

Friday 29th June 2007; Nottingham

Friday 14th December 1984

Friday 29th June 2007

Rotheswell Castle

Saturday 19th January 1985

Dysart, Fife

Friday 29th June 2007; Rotheswell Castle

Nottingham

Thursday 30th November 1984; Dysart

Friday 29th June 2007; Glenrothes

Saturday 30th June 2007; East Wemyss

Newton of Wemyss

Kirkcaldy

Rotheswell Castle

Monday 21st January 1985; Rotheswell Castle

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Friday 23rd January 1987; Eilean Dearg

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Rotheswell Castle

Saturday 30th June 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Sunday 1st July 2007; East Wemyss

Monday 2nd July 2007; Glenrothes

Campora, Tuscany

Peterhead, Scotland

Monday 21st January 1985; Kirkcaldy

Monday 2nd July 2007; Peterhead

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss

Monday 2nd July 2007; Peterhead

Campora, Tuscany

East Wemyss, Fife

Campora, Tuscany

Kirkcaldy

Boscolata

East Wemyss

Tuesday 3rd July 2007; Glenrothes

San Gimignano

Coaltown of Wemyss

San Gimignano

Edinburgh

Campora

Wednesday 4th July 2007; East Wemyss

Rotheswell Castle

Glenrothes

Hoxton, London

Dundee

Siena

Glenrothes

Edinburgh Airport to Rotheswell Castle

Thursday 5th July 2007; Kirkcaldy

Sunday 14th August 1983; Newton of Wemyss

Thursday, 5th July 2007

Glenrothes

Rotheswell Castle

Kirkcaldy

Celadoria, near Greve in Chianti

Thursday 26th April 2007; Villa Totti, Tuscany

Thursday 5th July 2007; Celadoria, near Greve in Chianti

Kirkcaldy

Boscolata, Tuscany

Friday 6th July 2007; Kirkcaldy

A1, Firenze-Milano

Rotheswell Castle

Friday 13th July 2007; Glenrothes

Wednesday 18th July 2007

Thursday 19th July 2007; Newton of Wemyss

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Copyright © Val McDermid 2008

Val McDermid asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007243297

Ebook edition © SEPTEMBER 2008 ISBN: 9780007287451

Version: 2018-11-05

Wednesday 23rd January 1985; Newton of Wemyss

The voice is soft, like the darkness that encloses them. ‘You ready?’

‘As ready as I’ll ever be.’

‘You’ve told her what to do?’ Words tumbling now, tripping over each other, a single stumble of sounds.

‘Don’t worry. She knows what’s what. She’s under no illusions about who’s going to carry the can if this goes wrong.’ Sharp words, sharp tone. ‘She’s not the one I’m worrying about.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing. It means nothing, all right? We’ve no choices. Not here. Not now. We just do what has to be done.’ The words have the hollow ring of bravado. It’s anybody’s guess what they’re hiding. ‘Come on, let’s get it done with.’

This is how it begins.

Wednesday 27th June 2007; Glenrothes

The young woman strode across the foyer, low heels striking a rhythmic tattoo on vinyl flooring dulled by the passage of thousands of feet. She looked like someone on a mission, the civilian clerk thought as she approached his desk. But then, most of them did. The crime prevention and public information posters that lined the walls were invariably wasted on them as they approached, lost in the slipstream of their determination.

She bore down on him, her mouth set in a firm line. Not bad looking, he thought. But like a lot of the women who pitched up here, she wasn’t exactly looking her best. She could have done with a bit more make-up, to make the most of those sparky blue eyes. And something more flattering than jeans and a hoodie. Dave Cruickshank assumed his fixed professional smile. ‘How can I help you?’ he said.

The woman tilted her head back slightly, as if readying herself for defence. ‘I want to report a missing person.’

Dave tried not to show his weary irritation. If it wasn’t neighbours from hell, it was so-called missing persons. This one was too calm for it to be a missing toddler, too young for it to be a runaway teenager. A row with the boyfriend, that’s what it would be. Or a senile granddad on the lam. The usual bloody waste of time. He dragged a pad of forms across the counter, squaring it in front of him and reaching for a pen. He kept the cap on; there was one key question he needed answered before he’d be taking down any details. ‘And how long has this person been missing?’

‘Twenty-two and a half years. Since Friday the fourteenth of December 1984, to be precise.’ Her chin came down and truculence clouded her features. ‘Is that long enough for you to take it seriously?’

Detective Sergeant Phil Parhatka watched the end of the video clip then closed the window. ‘I tell you,’ he said, ‘if ever there was a great time to be in cold cases, this is it.’

Detective Inspector Karen Pirie barely raised her eyes from the file she was updating. ‘How?’

‘Stands to reason. We’re in the middle of the war on terror. And I’ve just watched my local MP taking possession of 10 Downing Street with his missus.’ He jumped up and crossed to the mini-fridge perched on top of a filing cabinet. ‘What would you rather be doing? Solving cold cases and getting good publicity for it, or trying to make sure the muzzers dinnae blow a hole in the middle of our patch?’

‘You think Gordon Brown becoming Prime Minister makes Fife a target?’ Karen marked her place in the document with her index finger and gave Phil her full attention. It dawned on her that for too long she’d had her head too far in the past to weigh up present possibilities. ‘They never bothered with Tony Blair’s constituency when he was in charge.’

‘Very true.’ Phil peered into the fridge, deliberating between an Irn Bru and a Vimto. Thirty-four years old and still he couldn’t wean himself off the soft drinks that had been treats in childhood. ‘But these guys call themselves Islamic jihadists and Gordon’s a son of the manse. I wouldn’t want to be in the Chief Constable’s shoes if they decide to make a point by blowing up his dad’s old kirk.’ He chose the Vimto. Karen shuddered.

‘I don’t know how you can drink that stuff,’ she said. ‘Have you never noticed it’s an anagram of vomit?’

Phil took a long pull on his way back to his desk. ‘Puts hairs on your chest,’ he said.

‘Better make it two cans, then.’ There was an edge of envy in Karen’s voice. Phil seemed to live on sugary drinks and saturated fats but he was still as compact and wiry as he’d been when they were rookies together. She just had to look at a fully leaded Coke to feel herself gaining inches. It definitely wasn’t fair.

Phil narrowed his dark eyes and curled his lip in a good-natured sneer. ‘Whatever. The silver lining is that maybe the boss can screw some more money out of the government if he can persuade them there’s an increased threat.’

Karen shook her head, on solid ground now. ‘You think that famous moral compass would let Gordon steer his way towards anything that looked that self-serving?’ As she spoke, she reached for the phone that had just begun to ring. There were other, more junior officers in the big squad room that housed the Cold Case Review Team, but promotion hadn’t altered Karen’s ways. She’d never got out of the habit of answering any phone that rang in her vicinity. ‘CCRT, DI Pirie speaking,’ she said absently, still turning over what Phil had said, wondering if, deep down, he had a hankering to be where the live action was.

‘Dave Cruickshank on the front counter, Inspector. I’ve got somebody here, I think she needs to talk to you.’ Cruickshank sounded unsure of himself. That was unusual enough to grab Karen’s attention.

‘What’s it about?’

‘It’s a missing person,’ he said.

‘Is it one of ours?’

‘No, she wants to report a missing person.’

Karen suppressed an irritated exhalation. Cruickshank really should know better by now. He’d been on the front desk long enough. ‘So she needs to talk to CID, Dave.’

‘Well, yeah. Normally, that would be my first port of call. But see, this is a bit out of the usual run of things. Which is why I thought it would be better to run it past you, see?’

Get to the point. ‘We’re cold cases, Dave. We don’t process fresh inquiries.’ Karen rolled her eyes at Phil, smirking at her obvious frustration.

‘It’s not exactly fresh, Inspector. This guy went missing twenty-two years ago.’

Karen straightened up in her chair. ‘Twenty-two years ago? And they’ve only just got round to reporting it?’

‘That’s right. So does that make it cold, or what?’

Technically, Karen knew Cruickshank should refer the woman to CID. But she’d always been a sucker for anything that made people shake their heads in bemused disbelief. Long shots were what got her juices flowing. Following that instinct had brought her two promotions in three years, leapfrogging peers and making colleagues uneasy. ‘Send her up, Dave. I’ll have a word with her.’

She replaced the phone and pushed back from the desk. ‘Why the fuck would you wait twenty-two years to report a missing person?’ she said, more to herself than to Phil as she raided her desk for a fresh notebook and a pen.

Phil thrust his lips out like an expensive carp. ‘Maybe she’s been out of the country. Maybe she only just came back and found out this person isn’t where she thought they were.’

‘And maybe she needs us so she can get a declaration of death. Money, Phil. What it usually comes down to.’ Karen’s smile was wry. It seemed to hang in the air in her wake as if she were the Cheshire Cat. She bustled out of the squad room and headed for the lifts.

Her practised eye catalogued and classified the woman who emerged from the lift without a shred of diffidence visible. Jeans and fake-athletic hoodie from Gap. This season’s cut and colours. The shoes were leather, clean and free from scuffs, the same colour as the bag that swung from her shoulder over one hip. Her mid-brown hair was well cut in a long bob just starting to get a bit ragged along the edges. Not a doleite, then. Probably not a schemie. A nice, middle-class woman with something on her mind. Mid to late twenties, blue eyes with the pale sparkle of topaz. The barest skim of make-up. Either she wasn’t trying or she already had a husband. The skin round her eyes tightened as she caught Karen’s appraisal.

‘I’m Detective Inspector Pirie,’ she said, cutting through the potential stand-off of two women weighing each other up. ‘Karen Pirie.’ She wondered what the other woman made of her - a wee fat woman crammed into a Marks and Spencer suit, mid-brown hair needing a visit to the hairdresser, might be pretty if you could see the definition of her bones under the flesh. When Karen described herself thus to her mates, they would laugh, tell her she was gorgeous, make out she was suffering from low self-esteem. She didn’t think so. She had a reasonably good opinion of herself. But when she looked in the mirror, she couldn’t deny what she saw. Nice eyes, though. Blue with streaks of hazel. Unusual.

Whether it was what she saw or what she heard, the woman seemed reassured. ‘Thank goodness for that,’ she said. The Fife accent was clear, though the edges had been ground down either by education or absence.

‘I’m sorry?’

The woman smiled, revealing small, regular teeth like a child’s first set. ‘It means you’re taking me seriously. Not fobbing me off with the junior officer who makes the tea.’

‘I don’t let my junior officers waste their time making tea,’ Karen said drily. ‘I just happened to be the one who answered the phone.’ She half-turned, looked back and said, ‘If you’ll come with me?’

Karen led the way down a side corridor to a small room. A long window gave on to the car park and, in the distance, the artificially uniform green of the golf course. Four chairs upholstered in institutional grey tweed were drawn up to a round table, its cheerful cherry wood polished to a dull sheen. The only indicator of its function was the gallery of framed photographs on the wall, all shots of police officers in action. Every time she used this room, Karen wondered why the brass had chosen the sort of photos that generally appeared in the media after something very bad had happened.

The woman looked around her uncertainly as Karen pulled out a chair and gestured for her to sit down. ‘It’s not like this on the telly,’ she said.

‘Not much about Fife Constabulary is,’ Karen said, sitting down so that she was at ninety degrees to the woman rather than directly opposite her. The less confrontational position was usually the most productive for a witness interview.

‘Where’s the tape recorders?’ The woman sat down, not pulling her chair any closer to the table and hugging her bag in her lap.

Karen smiled. ‘You’re confusing a witness interview with a suspect interview. You’re here to report something, not to be questioned about a crime. So you get to sit on a comfy chair and look out the window.’ She flipped open her pad. ‘I believe you’re here to report a missing person?’

‘That’s right. His name’s -’

‘Just a minute. I need you to back up a wee bit. For starters, what’s your name?’

‘Michelle Gibson. That’s my married name. Prentice, that’s my own name. Everybody calls me Misha, though.’

‘Right you are, Misha. I also need your address and phone number.’

Misha rattled out details. ‘That’s my mum’s address. I’m sort of acting on her behalf, if you see what I mean?’

Karen recognized the village, though not the street. Started out as one of the hamlets built by the local laird for his coal miners when the workers were as much his as the mines themselves. Ended up as commuterville for strangers with no links to the place or the past. ‘All the same,’ she said, ‘I need your details too.’

Misha’s brows lowered momentarily, then she gave an address in Edinburgh. It meant nothing to Karen, whose knowledge of the social geography of the capital, a mere thirty miles away, was parochially scant. ‘And you want to report a missing person,’ she said.

Misha gave a sharp sniff and nodded. ‘My dad. Mick Prentice. Well, Michael, really, if you want to be precise.’

‘And when did your dad go missing?’ This, thought Karen, was where it would get interesting. If it was ever going to get interesting.

‘Like I told the guy downstairs, twenty-two and a half years ago. Friday 14th December 1984 was the last time we saw him.’ Misha Gibson’s brows drew down in a defiant scowl.

‘It’s kind of a long time to wait to report someone missing,’ Karen said.

Misha sighed and turned her head so she could look out of the window. ‘We didn’t think he was missing. Not as such.’

‘I’m not with you. What do you mean, “not as such”?’

Misha turned back and met Karen’s steady gaze. ‘You sound like you’re from round here.’

Wondering where this was going, Karen said. ‘I grew up in Methil.’

‘Right. So, no disrespect, but you’re old enough to remember what was going on in 1984.’

‘The miners’ strike?’

Misha nodded. Her chin stayed high, her stare defiant. ‘I grew up in Newton of Wemyss. My dad was a miner. Before the strike, he worked down the Lady Charlotte. You’ll mind what folk used to say round here - that nobody was more militant than the Lady Charlotte pitmen. Even so, there was one night in December, nine months into the strike, when half a dozen of them disappeared. Well, I say disappeared, but everybody knew the truth. That they’d gone to Nottingham to join the blacklegs.’ Her face bunched in a tight frown, as if she was struggling with some physical pain. ‘Five of them, nobody was too surprised that they went scabbing. But according to my mum, everybody was stunned that my dad had joined them. Including her.’ She gave Karen a look of pleading. ‘I was too wee to remember. But everybody says he was a union man through and through. The last guy you’d expect to turn blackleg.’ She shook her head. ‘Still, what else was she supposed to think?’

Karen understood only too well what such a defection must have meant to Misha and her mother. In the radical Fife coalfield, sympathy was reserved for those who toughed it out. Mick Prentice’s action would have granted his family instant pariah status. ‘It can’t have been easy for your mum,’ she said.

‘In one sense, it was dead easy,’ Misha said bitterly. ‘As far as she was concerned, that was it. He was dead to her. She wanted nothing more to do with him. He sent money, but she donated it to the hardship fund. Later, when the strike was over, she handed it over to the Miners’ Welfare. I grew up in a house where my father’s name was never spoken.’

Karen felt a lump in her chest, somewhere between sympathy and pity. ‘He never got in touch?’

‘Just the money. Always in used notes. Always with a Nottingham postmark.’

‘Misha, I don’t want to come across like a bitch here, but it doesn’t sound to me like your dad’s a missing person.’ Karen tried to make her voice as gentle as possible.

‘I didn’t think so either. Till I went looking for him. Take it from me, Inspector. He’s not where he’s supposed to be. He never was. And I need him found.’

The naked desperation in Misha’s voice caught Karen by surprise. To her, that was more interesting than Mick Prentice’s whereabouts. ‘How come?’ she said.