Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

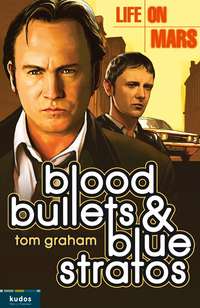

Czytaj książkę: «Life on Mars: Blood, Bullets and Blue Stratos»

TOM GRAHAM

Blood, Bullets and Blue Stratos

Table of Contents

Title Page

Chapter One: Out of the Ruins

Chapter Two: A Message in Red

Chapter Three: A Night at the Arms

Chapter Four: The Paddy Chain

Chapter Five: Handover

Chapter Six: An Audience with Gene Hunt

Chapter Seven: Letters of Blood

Chapter Eight: Test Card

Chapter Nine: Into the Lion’s Den

Chapter Ten: Captive

Chapter Eleven: Girl with a Gun

Chapter Twelve: Black & Decker

Chapter Thirteen: Empty Lair

Chapter Fourteen: Irish Eyes Aren’t Smiling

Chapter Fifteen: Interceptor

Chapter Sixteen: Sam Tyler, RIP

Chapter Seventeen: Together we Stand

Chapter Eighteen: Eat my Bullets

Chapter Nineteen: Showdown

Chapter Twenty: Mind Games

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

OUT OF THE RUINS

The man in the black leather jacket picked his way across a bleak terrain of broken buildings and burnt-out cars. Reaching the top of a low hill that was all smashed rubble and pulverized concrete, he glanced for a moment at the pale disc of the sun, then stumbled his way down into a dead valley where overturned lorries smoked and smouldered. Brick dust kicked up and clogged his nostrils. An acrid wind gusted along the valley, stinging his eyes. Half blind and choking, he sought shelter in the skeletal remains of a building that rose ominously from the wreckage.

He found himself inside a roofless ruin, all broken walls and empty, gaping windows. And yet, something in the layout of this place stirred up memories. This building had once been familiar to him. It had buzzed and thrived with life. He recalled uniforms, and desks, mountains of paperwork, banter, and bullying, and a rough camaraderie. Had it once been his school?

A sharp voice suddenly cut through the silence. ‘What you standing around like that for? This ain’t a bleedin’ bus stop.’

The man jumped and spun round. Behind a pile of stone and timber that may once have been a desk, a woman was staring sourly at him. That expression – unimpressed, implacable, not-in-the-mood-for-any-of-your-bloody-nonsense – was shockingly familiar.

‘I know you …’ the man muttered. ‘I know your name.’

‘Well bully for you, luv! Award yourself ten points.’

‘Phyllis. Your name’s Phyllis! We knew each other.’

‘In the biblical sense? In your dreams, sonny. Now shift your arse before I stick you in cell 3 with Dirty Dougie Corrigan. There’s a puddle of old sick in cell 3, and I’ve been told Dirty Dougie’s just dropped a shit in the middle of it, so unless you fancy getting handy with a mop and bucket then sling ya hook!’

Phyllis impatiently ushered him through a smashed doorway into the gutted remains of a large room. The ghostly echo of a clacking typewriter drifted through the dead building, a long-gone telephone rang, and the man in the leather jacket said out loud, ‘I worked here. I worked right here.’

He imagined his desk, his telephone, his chair – and then, unbidden, the image came into his mind’s eye of other desks ranged nearby, steel cabinets bulging with files, and police mugshots of wanted men pinned to the walls, jostling for space amid the photos of Page 3 girls and bygone footballers.

Without warning, a young man appeared, spectre-like, seated at his desk, his dark hair parted above his pale, not-quite-mature face. He studied something on his desk, some piece of paperwork, his eyes narrowing and his brow furrowing like a studious schoolboy hard at work.

‘What do you think?’ the young man said suddenly. ‘Looks a bit rough, this one. Reckon you could handle it, Ray?’

Another figure appeared behind him – older, stouter, with a blond moustache, sharp blue eyes and the hard edge of a man well used to showdowns and violence. He cracked his knuckles and leant over the younger man’s desk to examine the paperwork.

‘There’s nowt so rough it puts the frighteners on me, Chrissie-boy,’ he said. ‘Let’s have a close-up.’

He swept up the paper from the young man’s desk and scrutinized it. It was a dog-eared copy of Soapy Knockers magazine.

‘Not so rough as all that, Chris – not with the lights out an’ all. Yeah, I reckon I’d have a little go on this one, if she were drippin’ for it an’ that.’

‘I know you two,’ said the man in the black leather jacket. The two ethereal figures looked round at him. ‘Chris Skelton. Ray Carling. I know you … both of you …’

‘Both of us?’ asked Chris.

‘Or both of these?’ asked Ray, turning the magazine to reveal a massive pair of soapy breasts.

‘We worked together,’ the man in the jacket insisted. ‘In this room. Your desks were here – right here – and mine was here, and just over there was a … there was a woman … dark hair … her name was … her name was … oh, dammit, you boys remember. She was one of us and her desk was right there and she was called …’

His mind reeled, but the name would not come.

‘Why can’t I remember her name? Why can’t I remember?’

Ray exchanged a knowing look with Chris, then tapped the side of his head with his finger.

The man in the jacket saw the gesture and shouted, ‘There’s nothing wrong with my sanity. I know who I am.’

‘If you say so, boss.’

‘I know what’s real and what’s not. And I know that woman’s name. She sat right there and here name was … her name was …’

Furiously, the man grabbed a brick and hurled it against the remains of a wall.

‘Got a temper on ’im, this lad,’ winked Ray.

‘P’raps he should go up against big ’Enry,’ said Chris.

‘That’s what you said before.’ The man in the leather jacket jabbed his finger at Chris. ‘When I first came here, you said – you said I looked like I’d gone ten rounds with big Henry. It’s what you said when I first walked through that door.’

‘What door, boss?’ asked Chris.

Where the door had once been there was now only a ragged hole and heaps of rubble.

‘Ain’t no door here,’ said Ray, chewing his gum. ‘Ain’t nothing no more.’

‘All broken,’ said Chris.

‘All gone.’

‘Busted.’

‘Like you, boss. Broken, and busted.’

The man in the jacket looked from Chris to Ray and back again. ‘What do you mean by that?

‘There’s nothing here for you,’ said Ray, fishing out a cigarette from his breast pocket and sparking it up. ‘You could have gone back where you belong. You had your chance. But you threw it away. You threw yourself away. Don’t you remember?’

Chris turned his fingers into a pair of walking legs and mimed them running, jumping, plummeting. He made a long, descending whistle that ended with a splat.

The man in the jacket backed away, his hands clutching the sides of his head. His mind was reeling. Memories were swilling wildly about inside his skull: of standing atop a high roof with the city laid out all around him; of making a decision, and then starting to run. He remembered sprinting, leaping, falling, an expanse of hard concrete rushing up to meet him.

‘Topped yourself, boss,’ said Chris, taking back his copy of Soapy Knockers and leafing through it. ‘Smashed yourself to pieces.’

‘And everything else along with you,’ put in Ray, letting smoke trail from between his lips. ‘Just look around. See what you done.’

‘I remember …’ the man stammered, trying to piece together the jostling fragments in his mind. ‘The year was … It was 2006. There was an accident. I got … I got shot …’

‘Run over,’ Chris corrected him. ‘Very nasty.’

‘Run over … yes, yes,’ the man said, starting to see the pattern of events forming. ‘And I woke up … But it wasn’t 2006 any more … It was nineteen … It was nineteen-seventy … nineteen-seventy …’

‘… three,’ Chris and Ray intoned together.

‘Nineteen seventy-three. Yes, that was it,’ said the man. ‘I didn’t know if I was mad, or dead, or in a coma …’

‘Or a mad, dead bloke in a coma,’ piped up Chris. ‘Three for the price of one.’

‘But I did know I had to get back home, back to my own time, back to 2006. And I did it. I got there. But then, it was like … It felt like …’

‘Being dead?’ suggested Ray.

‘Being in a coma?’ added Chris. ‘Being a mad dead bloke in a coma all over again?’

‘Yes,’ said the man in the jacket. ‘It did feel like being a mad dead bloke in a coma. And I realized then I didn’t belong there after all. I belonged here, in 1973.’

‘But this ain’t 1973, boss,’ said Ray, staring flatly at him. ‘It ain’t nowhere.’

‘Hell, maybe,’ shrugged Chris.

‘Same thing,’ said Ray.

‘No,’ said the man. ‘No, that’s not true. I came back to 1973. I jumped off a rooftop in 2006, and I landed here – in ’73 – where I belong.’

‘You landed nowhere,’ said Ray. ‘Sorry, boss – you ballsed it up. You should’ve stayed in your own time. There’s nothing here for you – no life, no future. Still … Too late now. Too late.’

The man in the jacket seemed about to faint. He reached out to a desk for support, found it was as insubstantial as a wisp of smoke, stumbled, and fell against a broken wall.

‘He’s done his head in, Chris,’ said Ray, a grin just beginning to flicker beneath his moustache. ‘Must have been when he hit the ground.’

Chris nodded sadly. ‘Bumped his noodle. Concussion.’

‘And then some.’

‘Skull would have shattered like a vase.’

‘Brains all over the place.’

‘Scrambled eggs.’

‘Stewed tomatoes.’

Ray winced. ‘And his dear old mum called in to identify the scrapings.’

‘Bet that did her head in,’ Chris suggested.

Ray nodded, drawing deeply on his cigarette, narrowed eyes fixed on the man in the jacket. ‘Bet it did. Still – he reckons he did the right thing.’

‘I … I did the right thing,’ the man in the jacket said, straightening up and trying to sound as if he believed it. ‘I had to come back here … I had to.’

‘If you say so, boss,’ shrugged Chris.

‘It was important to come back. I – I know it was important …’

Ray laughed. ‘You know nowt. Not even your own name.’

‘I know who I am.’

‘Tell us then. Who are you? Eh? Go on.’

The man in the jacket opened his mouth, but was silent. Ray snorted with derision, and then Chris began laughing too. And, as they laughed, a cold wind moaned, and, like pillars of sand, the figures of Chris and Ray evaporated, along with the desks and filing cabinets.

‘Don’t you go!’ the man in the jacket cried out. ‘I know who I am!’

‘You ain’t no one, not any more,’ grinned Ray, and with that he and Chris were gone.

‘I know who I am!’ the man yelled into the empty room. ‘We were a team. There were you two, and me, and the woman over there … And a fella. A big fella. The boss. Our boss. The guv’nor. That’s it! He was our guv. And we were all coppers. You remember. You remember me. My name’s … Oh, for God’s sake, you remember my name, it’s … My bloody name is …’

He stuttered, stammered, then punched the air in fury. What the hell had happened to him? Why couldn’t he remember? Was his mind as smashed and broken as everything else round here?

Smashed … Broken …

As if reading his thoughts, the roofless walls about him groaned and shifted. Great cracks shot across the bare plaster like zigzags of lightning, filling the air with choking clouds of dust. Masonry began to topple and crash. Even the floor heaved and fractured.

Covering his mouth and nose with one hand, and wildly fending off the cascades of shattered brickwork coming down about him, the man in the leather jacket stumbled his way back into the bleak valley. Throwing himself clear, he turned and watched the shell of the police station crumple in on itself, like the brittle remains of an Egyptian mummy crumbling away on exposure to the air. In seconds, there was nothing standing – just another mound of rubble amid many, wreathed in an aura of concrete dust that began slowly to settle.

As the man in the leather jacket got back on his feet, there came an unearthly noise, very different from the crack and blast of collapsing masonry. It was a weird, scraping, groaning sound that instantly released a flood of memories in the man’s mind: teatime; waiting for the telly to warm up; a whirling tunnel of light; a terrifying theme tune that sounded like the scream of a killer robot; a sofa behind which he felt compelled to hide.

The man glanced anxiously about, then clambered frantically to the crest of a heap of twisted girders to get a wider view. A blue police box slowly materialized in the flat base of a valley amid the wreckage. The sound ceased, and for some moments the box sat silent and inert. Then the door opened, and a woman emerged – the woman, the woman whose face he could see in his mind’s eye but whose name had completely eluded him.

‘Annie …’ The man breathed, and his heart leapt at the sight of her. ‘Annie Cartwright …’

But she was not quite as he remembered her. Her dark hair had turned mousy blonde; she was dressed in a drab pinafore dress and dull, floral-pattern blouse the man was sure he had never seen her wear before. Why? Why had she made herself look like Jo Grant from some old episode of Doctor Who?

‘Where are we?’ she said, speaking to somebody behind her. ‘Doctor?’

Like Annie, Jon Pertwee had changed too. The grey bouffant was the same, as was the velvet smoking jacket, ruffled shirt and floppy bowtie; but the gut was stouter, the chest more barrel-like, the stance more confrontational, the aftershave more potent. The hair and costume were the Doctor’s, but the man inside them was an altogether different animal.

The man in the leather jacket felt a sickening lurch of recognition. That was him, that was the fella – it was the guv.

‘What is this place, Doctor?’ Annie asked.

‘A chuffing shite-hole, luv,’ Doctor Hunt replied, scowling about at the bleak landscape. ‘Looks like I’m going to have reprogram the TARDIS’s intergalactic coordinator circuits with the toe of my size-twelve boot.’

‘We’re not staying, then?’

‘Not unless you fancy taking a slash in the gravel like a white-arsed collie. C’mon, luv – bounce your clout back in the box and get us a brew on the go.’

He smacked Annie’s backside as she disappeared back into the TARDIS, then jammed a half-smoked panatella into his gob as he took one last, unimpressed look around.

‘Gene!’ the man in the leather jacket cried out, the name coming to him in flash. ‘Gene Hunt! Guv. Wait. Don’t go.’

Gene sucked on the cigar, oblivious of the man’s cries.

‘Gene! Please! Don’t leave me here!’

Gene disappeared inside the TARDIS and slammed the door. A heartbeat later, the police box began to dematerialize.

‘No! Wait, Guv! It’s me! Don’t leave me here! We’re a team! We’re a team, you rotten bastard!’

Just before the TARDIS disappeared entirely, the doors opened enough to reveal Gene’s hand, two fingers flicking a ‘V’, before they and the blue police box evaporated entirely.

‘Don’t leave me here. I want to go home!’

All at once he was struggling against something that smothered and suffocated him, and in the next moment he found himself caught up in tangled bed sheets, his face sunk deep into a sweat-soaked pillow. He sat up, getting his breath back, and glared about him, momentarily shocked to find that the wasteland of rubble had been replaced with the familiar surroundings of his flat: beige and brown wallpaper, flower-patterned lampshades, a huge black-and-white TV with clunky buttons, a hot-water boiler that took forever to warm up. Beyond his nicotine-coloured curtains, a cold grey day was dawning over Manchester. From some distant street came the wail of a panda car. Somebody in a nearby flat was playing ‘Whiskey in the Jar’ on a tinny transistor radio.

Home.

The man clambered slowly from the tangled sheets, padded across the rough nylon carpet, and confronted himself in the bathroom mirror. What he saw was a face just the right side of forty, with narrow, thoughtful features starting to bear the lines of too many worries, too many unresolved dilemmas, too many restless nights.

‘It was just another bad dream,’ the face told him. ‘Don’t let it rattle you.’

He ran his hand across his close-trimmed hair, ruffled the jagged fringe running across his high forehead.

‘You know exactly who you are. Your name is Sam Tyler.’

Above his narrow, thoughtful eyes, the brows knotted anxiously. He rubbed at them to smooth out the lines.

‘You are Detective Inspector Sam Tyler of CID, A-Division.’

Detective Inspector. The rank still irked him. Back in 2006, he had been a fully fledged DCI – a detective chief inspector. It had been DCI Tyler who had pulled his car over to the side of the road, David Bowie blaring out of the dashboard MP3 player. It had been DCI Tyler who had stepped out of the car, trying to clear the tumultuous whirlwind of his thoughts, too preoccupied with his worries to even notice the other vehicle bearing down on him. It had been DCI Tyler who had felt the sudden impact of that vehicle, followed at once by the equally sudden impact of the tarmac. It had been DCI Tyler who had lain there, eyes unfocused, his consciousness ebbing away, the voice of Bowie penetrating the blankness that seemed to be overtaking him.

And her friend is nowhere to be seen

As she walks through a sunken dream

‘You know who you are and where you are,’ Sam told himself, looking his reflection firmly in the eye. ‘You are where you belong. Right here. This is your home.’

His home. Nineteen seventy-three. How strange and alien it had felt when he had first crash-landed here, alone and disoriented like a man from Mars. He had hunted through his pockets for the familiar props of the twenty-first century – the mobile, the BlackBerry, the sheaf of plastic debit cards – and found nothing but ten-pence pieces the size of doubloons and an ID card informing him that he was no longer a DCI but a detective inspector transferred down to Manchester from Hyde. He had tugged at his winged shirt collars and the tops of the Chelsea boots that he found himself wearing, and blundered like a zombie through the once-familiar police station that should have been buzzing with PC terminals and air-conditioning units but was now heavy with the clacking of typewriters and the sparking-up of cigarette lighters.

‘This is my office – here!’ he had bellowed, surrounded by blank, uncomprehending faces. ‘This is my department! What have you done with it?’

The answer had not come from the men staring at him. It had come in the form of a deep, phlegmy rumble, and the sound of heavy feet scraping across the floor. The man had turned, and there, lurking like an ogre in the smoke-filled den of his office, had been his new DCI – Gene Hunt, the guv – the shaven stubble of his neck red and inflamed from the raw alcohol that passed as aftershave, his belly bulging at the buttons of his nylon shirt, his stained fingers forever reaching for the next packet of fags, or the next glass of Scotch, or the next villain’s windpipe. He had introduced Sam to his new department with a breathtaking blow to the stomach – ‘Don’t you ever waltz into my kingdom acting king of the jungle!’ – and oriented him in Time and Space with a little less technical detail than Einstein or Hawking. ‘It’s 1973. Almost dinnertime. I’m ’avin’ hoops.’ And Sam, slowly but surely, had come to realize that he could be happy here. This place had life – hot, stinking, roaring, filthy, balls-to-the-wall life.

It also had Annie.

Sam ran water into the basin and splashed it across his face, thinking of Annie Cartwright. From the very moment he’d first met her, he had felt a connection, a conviction that, of all the strange characters populating his new world, she was the one he could trust the most. And in time she had become the bright heart of his universe around which everything else orbited. It was her as much as anything else in this place that he had missed so bitterly when he had returned to 2006, and it was her face that had been foremost in his mind when he had leapt so joyfully from the rooftop and plunged back into 1973. The future – his future – was with her. No question of that. He had thrown away his own time and his old life to ensure that.

And yet, night after night, the dreams battered away at him, always telling him the same thing: that he had no future, least of all with Annie; that coming back here had been a terrible mistake, far more catastrophic than he could imagine; that what life he had here in 1973 was destined to end in ruin and pain and utter despair.

‘Just dreams,’ he told his reflection. ‘Meaningless.’

But something deep within him seemed to say, Ah, but you know that’s not the case.

‘I have a future.’

You know that’s not true.

‘And it’s with Annie. We’ll be together. And we’ll be happy.’

Sam, Sam, you can’t kid yourself for ever.

‘We’ll make it, me and Annie – no one, and nothing, is going to stop us.’

Bash! Bash! Bash!

A fist pounded massively at the door like gunfire.

‘Who the hell is it?’ Sam shouted.

An all-too-familiar voice bellowed through the keyhole back at him. ‘Sorry to interrupt any intimate encounters you might be enjoying with Madam Palm and her five daughters, Sammy, but I just thought you might find the time to nick a few villains.’

Sam sighed, padded over to the front door and opened it. Filling the doorway loomed a barrel-chested grizzly bear dressed in a camelhair coat and off-white tasselled loafers. The reek of stale Woodbines and Blue Stratos shimmered about him like a heat haze. His black, string-backed driving gloves creaked as his implacable hands flexed and clenched. Peering down at Sam as if unsure whether to ignore him completely or batter him into the ground like a tent peg, this rock-solid, monstrous, nylon-clad Viking narrowed his cold eyes and jutted out his unbreakable chin.

This was him. This was the man. This was the guv. This was DCI Gene Hunt. Up close to him like this, eclipsed by his massive shadow, Sam felt vulnerable and absurd dressed in nothing but a T-shirt and shorts.

‘Fetchin’ little outfit, Sambo,’ Hunt intoned. ‘Are you trying to seduce me?’

‘Actually, Guv, I was contemplating a metaphysical dilemma.’

‘I hope you flushed afterwards.’ He swept past Sam and planted himself in the middle of the flat. The room seemed too small to contain him. He glared around him, his brooding glance seeming almost powerful enough to shatter windows. He rolled his shoulders, stuck out his chest and tilted his head, making the vertebrae of his neck give off an audible crack. ‘Excuse the early-morning house call, Tyler, but duty is calling. We got a shout. A to-do. A right bleedin’ incident.’

‘What sort of incident?’ asked Sam, hopping into his trousers.

‘Terrorists.’

‘IRA?’

‘No – disgruntled Avon ladies. Of course it’s the bloody IRA, Sam. Now zip your knickers up and get yourself decent.’

‘Any chance of you giving me a few details about what’s happening, Guv?’ asked Sam, shrugging on his black leather jacket. ‘Or have we got another couple of hours of sarcasm to get through first?’

‘Don’t get shirty, Mildred,’ said Gene, turning on his heel and leading the way out through the door. ‘I’ll fill you in on the way. It’ll take your mind off my driving.’

Darmowy fragment się skończył.