Czytaj książkę: «I Remember - Ich denke an ...»

I Remember –

Ich denke an …

Tanya Josefowitz

Edited and annotated with an afterword by

Herausgegeben, ins Deutsche übersetzt, mit Anmerkungen

und einem Nachwort versehen von

Jörg W. Rademacher

Table of contents / Inhaltsverzeichnis

Worms, where I was born and where we lived,

Once on the moving train, it was like turning a page of my life

On our way to Le Havre we spent 24 hours in Paris.

On the day of arrival Mother again was simulating emotion rather than illness.

In Germany I don’t recall ever having been allowed alone on the street,

In 1933/34 Vladi and I went to a Kindergarten run by nuns, where we were very happy.

When Mother had fully recovered,

I feel I had to write this true story …

I wish also to remember those 30 members …

I want to thank …

Photographs/Photographien

Worms, wo ich geboren wurde und wo wir lebten,

Als wir im fahrenden Zug saßen, schien es mir, als sei in meinem Leben eine neue Seite aufgeschlagen.

Auf unserem Weg nach Le Havre verbrachten wir 24 Stunden in Paris.

Am Ankunftstag simulierte Mutter erneut Gefühle, statt Krankheit.

Ich entsinne mich nicht, in Deutschland je allein auf die Straße oder in einen Park gedurft zu haben …

1933/34 gingen Vladi und ich in einen von Nonnen geleiteten Kindergarten, wo wir sehr glücklich waren.

Nach Mutters völliger Genesung …

Mich drängte ein Gefühl zur Niederschrift meiner eigenen Geschichte

Denken möchte ich auch an jene 30 Mitglieder …

Danken möchte ich …

Editor’s afterword

Nachwort des Herausgebers

Acknowledgments / Danksagungen

Picture credits / Abbildungsnachweise

Editor’s notes / Anmerkungen des Herausgebers

Index of names and places / Namens- und Ortsregister

I REMEMBER

Tanya Josefowitz

Edited and annotated with an afterword by Jörg W. Rademacher

This is the second book authored by Tanya Josefowitz, while the first, entitled Capinero. A Bird, was privately published in Switzerland in 1992. Discovered in May 2019, it is in the process of being edited and translated, and it will appear in due course.

Editor’s note, January 2021

Ilya Kagan arrived in Worms as a Russian Prisoner of War in 1914. Interned, he created a carpenter’s workshop, producing furniture and training people, thus doing useful work and gaining friends. Once well-integrated, he decided to stay on in Worms.

J. W. R., editor

I dedicate this book to all the generous people who have the courage to vanquish their fears in the face of unquestionable danger, in order to help others in imminent oppression.

T. J., London, June 1999

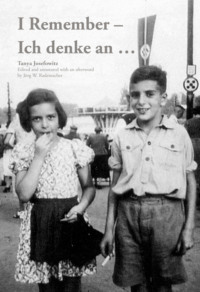

Tanya Kagan at age 12.

Worms, where I was born and where we lived, was a small but beautiful old town1. My parents were quite well known there and everybody seemed to like them, including the officials of the city who would close an eye to the warm relationships they had with Christian friends. Many of my parents’ friends were not Jewish, and after Hitler’s rise to power they were not permitted to mingle with Jews. In spite of it, as food for Jewish people was rationed, my parents’ friends would secretly come at night with baskets full of eggs, cheese, meat, butter, etc. concealed under some cloth.

I remember the one particular crucial night when we had such visitors. It was around 9.30 in the evening in March 1938.2 My brother Vladimir and I were already in bed. He was nine and a half and I was eight years old. In the next room we heard the guests and parents laugh and talk in hushed voices. They seemed quite animated and full of fun. Outside, as usual, there was the click and clack of booted feet marching in unison along the cobblestone pavement under our nursery window.

The Gestapo always marched in groups, wearing high boots with metal tips and heels whose rhythmic sound could be heard all over town. Vladimir and I had gotten used to these sounds. But that night, when the loud steps came to a sudden halt outside our house and when the door bell hit us like a bolt, we sat up in bed, all ears, frozen and paralysed with fear.

The intimate, cheerful conversation in the sitting room had also come to a stop. I heard my parents open the front door and close it after a moment. Then the click clack in the street resumed its course and faded into the night. We peeked through the slit of our door and saw the friends gathered around my parents. They were all frantically busy, reading the letter that had just been delivered. Then everybody began to speak at the same time, and the ominous sound of their frightened voices made me fearful, as I strained to hear what was being said.

Mother realized our door was open and saw our little faces peeking through. She reassured us and tucked us into bed. But for a long time I couldn’t sleep, trying to understand what was going on, and feeling that a terrible message must have been in that letter. In the morning Mother explained to us that we had to leave Germany very quickly. There was great hustle and bustle in the house. Many friends came to help pack. There were phone calls all day long, and we were told to keep out of the way and to stay in our rooms. We felt totally confused and isolated, particularly when it turned out that Father had to depart in a great hurry, and that he was going far away.

The hand-delivered document was an official notice informing us that we, the whole family Kagan, being Russian Jews, were ordered to leave Germany within exactly ten days. If we did not comply and stayed even one additional day, we would be deported and put into a concentration camp.

During the First World War, Father had been taken a Russian prisoner in Germany. After the war he did not wish to return to Communist Russia. Though he kept his Russian citizenship, he was more than happy to remain in Germany where he had made many good friends. Thus he stayed on to work and to enjoy his freedom. When he met Hildi Wallach3, my beautiful mother, it was love at first sight.

They got married, had two children, and as he had retained his Russian citizenship, my German born mother and her children automatically had to become Russians as well. Ironically, this was now one of our saving graces. As Russian Jews we were forced to leave Germany and thus had a chance to save our lives.

At that time, I understood very little of what was happening. But I was terrified and full of apprehension even before the fatal night of our expulsion. Our gentle, cozy home had suddenly become a fearful place, and everything seemed to fall apart.

Two days after receiving the expulsion letter, my father left for Bremen where he was to catch the “Manhattan”, the very next boat for New York. In Bremen he was lodged by a Catholic friend, a silversmith, who escorted him to the boat, wished him well and sent him off with a bottle of brandy.

Father traveled on a visitor’s visa sent to him by his sister Mary who lived in New York. He had had it for several years and kept renewing it, as he could never tear himself away from his family. Now he was only too happy to use it, for he was convinced that once in the USA, he would be able to acquire visas for us all and to have us follow him. His departure left us feeling completely lost and in a total turmoil. All we were allowed to ship to our next destination was a large box – called a container – with some furniture and whatever we could squeeze into it. Friends, neighbors, Jews and non-Jews, all came to help us and so did my mother’s father who later on, with the assistance of friends in the Vatican, managed to escape to the United States with my step-grandmother.

We left Worms, our home, our friends, our past for a completely unknown future, and our first stop was in Munich to say good-bye to my grandmother. Vladimir and I stayed with our beloved granny Emma. It was the very last time we saw her. She was later deported and died in Theresienstadt.

We still needed visas for any country that would harbor us on our way to the United States. There were many disappointments. My grandfather, a prominent Munich citizen and former War Veteran, was very well to do with many connections in the outside world.

His efforts to get us visas were of no avail. Nor could my mother’s sister in Denmark or her brother in Spain be of any help. She was married to a Protestant and relative of a famous Danish writer and her brother’s wife was a Spanish Catholic. But all this did not open any doors.4

After all our possibilities seemed exhausted, my mother suddenly remembered some Jewish friends who with their family, a few years ago, had emigrated to France. She contacted them in Metz where they were living and luckily! – they were able to get us a two months’ visa to stay in France. This, however, was finalized on the very last and dreaded tenth day of our residence permit in Germany. If by then we had not left the country, we were to be deported to some concentration camp. We therefore had to leave immediately.

The container5 had been shipped to the USA, and all we had with us were three small suitcases and the equivalent of $200,00, the only money we were permitted to take out. With warm, hopeful send-offs and tears, yet much relieved, we finally took off after emotionally loaded good-byes at the station.

It was a cold, gray day in the middle of March 1938. Mother was 32 [in fact, 34] years old and though her heart was trembling, she showed great courage and put on a cheerful air for the sake of her two children. We left on the train to Saarbrücken, a border town6, where we were to catch our connecting train at 7.00 p.m. to Metz in France.

Once on the moving train, it was like turning a page of my life. After the painful separation from all that was secure and dear to me I felt almost elated, as if we were on our way to a new phase of freedom and maybe to a life without fear. The train was chugging along. There was a smell of burnt coals as smoke slid past our windows. We were alone in our compartment.

Suddenly I looked up and saw my mother’s face turned pale. She produced a document out of her handbag and with a trembling voice she read out to us the frightening words of our “Ausweis”7 with its official stamp and date: our German permit had expired the previous day. We should have been out of Germany today. Mother was panic stricken. She felt that this document could cause us problems at the border and that she had to get rid of it. Against Vladi’s advice, while I was crying bitterly, frightened and confused, she tore it up into bits and pieces which she threw out of the window of the moving train, like flurries of snow flying in the wind. She closed the window and we huddled together, waiting silently for our arrival in Saarbrücken scheduled for 6.00 p.m.

When we reached our destination, few people got off the train and the platform was almost empty. We stood there with our few belongings, trying to decide what next, until my big brother Vladi, bright and attentive, spotted the “Zollamt”8, the Customs Office. We slowly crossed the silent station, and after a moment’s hesitation we went to it. We were met by a Gestapo man with ice blue eyes and a face cut in steel. He was dressed in Gestapo uniform, all in black: the tightfitting belt around his slim waist, the shiny boots and the typical casket with its Nazi insignia on his hat and on his jacket.8a

He motioned us into his office and ordered Mother to show her papers. With trembling hands she handed them over. He skimmed through them and then insisted that an important document was missing with an official stamp and a permission to leave Germany and to enter France. Without it he categorically refused to let us catch our 7 o’clock train to France. Our hearts sank. … Mother tried to explain how and why she tore up the missing document and that she had been afraid it would detain us, and cause problems. But he said: “No, madam, it is now that you have a problem. There is no way I can let you leave Germany. You must wait for tomorrow. …” Until then we would not be allowed to leave the station. We had to spend the night in the “Bahnhof Buffet”9. He took us there and left us – in this bleak, empty, cold, so-called “restaurant”.

I remember the one light bulb hanging down on a wire over our heads, the table bare, made of cheap wood full of greasy stains. The benches we sat on had no backing, and were too narrow to recline or to rest on. Vladimir had to go to the toilet, which was just outside the “Buffet”. He returned quickly rather upset. The toilet “lady” asked him for money for the use of the toilet. He had none. So she refused him. Mother had already changed all our money into French francs. Instead, she gave Vladimir an apple for the lady who took it and let him use the toilet.

Reunited in the “Buffet”, we nibbled on our picnic. Vladimir tried to cheer us up and played some German melodies for us on his accordion. It did make us forget for a moment where we were and we even laughed a bit.10 Soon we were alone in the “Buffet” as it closed down for the night. We tried to rest, or even to catch a wink of sleep. It was cold and bleak outside, but it was very cold inside as well, with bad light and horrid gray walls. Alone and frightened, we rested our heads on the table and cuddled together. But we could not sleep. I stopped crying but from time to time a tremor went through me.

We waited for the night to pass, not knowing what horror would befall us in the morning. In the silence of the night, the station seemed totally deserted, no more trains arriving or leaving. Sometimes we heard a distant whistle, or voices. But suddenly there were footsteps and the door was opened. In came a man in the same uniform as the one worn by the officer with icy eyes. This man, however, had a kinder face. At first glance we were startled by him, but not terrified. He said in a gentle voice, “Woman, what are you doing here in the middle of the night with two little children?” Mother explained how and why we had been detained and forced to spend the night in this waiting room. The man looked at us, obviously distressed. Then he said: “No, you cannot spend the night in this place.” He told us to take all our belongings, and in the cold of the night, on the empty station, he urged us to follow him back to this office where we had previously been. He insisted that we sit down, and as I was crying, he reassured me not to be afraid. Then he made a series of phone calls, trying unsuccessfully to find a place for us to spend the night. Even the “Jewish Community House” had no room and offered to put us up in a hotel. For some reason he didn’t accept their offer, said he would take care of us himself, and whisked us off to a hotel, across from the station.

We arrived in an empty, dreary lobby with a prominent picture of Hitler above the concierge’s desk. Our Gestapo man paid for a single room for the night, and reminded Mother to be back in his office at the station at 7.00 a.m. on the dot. Once together in the little room, we were in heaven. Vladimir and I were tucked in the single bed – sardine fashion – and Hildi, my exhausted mother, sat up in an armchair facing us. On the dreary beige, flowered, papered wall there was another picture of Hitler. We were too shaken and scared to get a real sleep. But at least we dozed off a bit in the quiet, heated room and had a little rest, regardless of the occasional eerie click clack of roaming Nazi officers patrolling the streets.

By 6.00 a.m. we were up sharing half of the single breakfast allotted to us. With the other half mother made “Butterbrot”11 sandwiches, as we didn’t know when we would eat again. At 7.00 a.m. we were in the Nazi Customs Office. Our friend and guardian angel, traitor to his cause, was there to greet us. We so much wanted to show him our gratitude. Yet we were too afraid of his uniform and all that it stood for to really trust him and to show our feelings.

He took us to the bleak “Bahnhof Buffet” and treated us to hot chocolate. Then he told me and Vladimir to watch our luggage and sit tight while he and Mother were going to get the necessary permission for us to leave Germany. They promised to be back in no time. But again I burst into tears and started screaming. People were looking at us, and again Vladimir began to play his accordion to cheer me; but I continued to cry, sure that we would never see our mother again.

Later, Mother told us how they ran to catch the tram and how our new friend virtually pushed her into it. When they got off, he said to her: “Now, please, keep your mouth shut! I’ll do the talking.”

They went to an official building with a big Nazi flag blowing in the wind. Many people were queuing up outside, but he pushed Mother past all of them and ran with her upstairs. They entered an office where a stern-looking bureaucratic official was sitting behind a big desk. Once more our man pushed Mummy forward and said: “I have here a fine Jewish lady who needs help in a hurry. Her children are alone at the station.” He then shoved onto his desk a paper that he had already filled out, and said that he just needed an “authorized” stamp from him that would be the passport for our departure to France. With great reluctance the Nazi stamped the paper, and off they fled, down the stairs, past the long queues, onto the tram and back to the station. “I wish I too could leave with my family,” he had told Mother whispering. But Hildi was still terrified and afraid to trust this man – even to cast him a smile. She was too traumatized, and almost to the last moment she suspected that this kind man might be fooling her.

Without delay our guardian angel rushed us onto the platform to catch the 9 o’clock train to France. He helped us to collect our belongings and pushed us onto the train. As Mother was about to board it, the dreaded officer of the day before appeared. Stern, and with angry eyes, he shouted: “This woman must be examined.” “Our” Gestapo officer then explained to Hildi that she must hurry to the little tent-like house on the platform, where a woman would examine her. Vladimir and I had to remain on the train. We watched Mummy run off and again I started to scream. She, too, turned back to us with saddened, frightened eyes while she was running.

Ushered into the tent-like hut, Mother was met by a tall, tough-looking, angry woman dressed in white like a nurse. She made her undress and examined every hole and crevice of her body. But outside, our good friend was waiting for her and rushed her off, yelling: “Hurry, hurry! Don’t dress, but just come as you are!” She barely man-aged to cover herself with the coat, then she rushed off to her children on the train, holding on to her clothes and shoes, while the long laces of her corset were sweeping the floor. Breathless and flushed, she grabbed the railing as “he” pushed her onto the slowly moving train. He stood there waving to us until we were out of sight and we too waved back, finally convinced that he really was our Friend and Saviour. We did not even know his name, and would probably never see him again. This was good-bye for ever! Next to him stood the other Nazi officer, observing the scene with cold eyes and an angry face. The train was almost empty. We sat in silence, each with his own thoughts, and I remember saying a hushed prayer for this man who, I was convinced, had saved our lives. We watched the bleak countryside slide past our window, and before we knew it, the conductor announced our arrival in Metz – our next home for a while.

Of course, no one was there to meet us at the station. Our friends had given up all hope of ever seeing us again. When we had not arrived at the announced date, they were sure we had been deported. What a relief and joy, when we three bedraggled and tired people walked into their simple but kind and welcoming home. We only stayed a few weeks, but to me the days and nights were like one, and they seemed endless. I had taken ill with a very bad and constant belly ache, and the doctor foresaw the worst. He thought that I needed an appendectomy.

In the meantime my father, by then in New York, had been able to get us immigration visas for the United States, with the help of Aunt Mary, Uncle Max12 and their children. It was a great dilemma for my mother: should she travel with a very [sick] child13, or miss the next boat, on which they had managed with great difficulty to obtain a cabin for the three of us. It was to leave from Le Havre in a few days.

Mother made the right decision and we were going to sail, in spite of my terrible belly pain. We left our friends in Metz with warm goodbyes and thanks. When the war was over, we found out that they had been deported and killed by the Nazis.14

Darmowy fragment się skończył.