Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «A Random Act of Kindness»

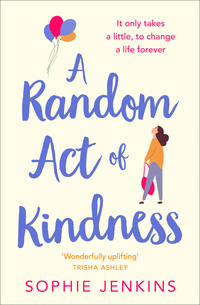

A RANDOM ACT OF KINDNESS

Sophie Jenkins

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2019

Copyright © Sophie Jenkins 2019

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com

Sophie Jenkins asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008281830

Ebook Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008281854

Version: 2019-05-20

Dedication

Dedicated to Rowena Jenkins

19.10.1931–3.12.2018

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Lot 1

Lot 2

Lot 3

Lot 4

Kim

Lot 5

Lot 6

Kim

Lot 7

Kim

Lot 8

Lot 9

Kim

Lot 10

Lot 11

Lot 12

Lot 13

Lot 14

Kim

Lot 15

Lot 16

Kim

Lot 17

Lot 18

Kim

Lot 19

Lot 20

Lot 21

Lot 22

Lot 23

Kim

Lot 24

Lot 25

Kim

Lot 26

Lot 27

Lot 28

Lot 29

Kim

Cato Hamilton Auctioneers & Fern Banks Vintage Auction Catalogue

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

Also by Sophie Jenkins

About the Publisher

LOT 1

A Chanel-style black-and-white cotton tweed suit with bracelet-length sleeves, double ‘C’ gilt buttons, chain-weighted hem and matching skirt.

Most stories start with action. This isn’t one of them. Mine starts with indecision. It’s a warm Sunday evening and I’m dragging my wheelie case over the cobbled stones of Camden Market, pondering the big issues of my life. Can I really make a living selling vintage dresses from one small stand? Should I call in at Cotton’s Rhum Shack to cheer myself up before going home?

The din of the case rattling on the cobbles is attracting some negative attention from passers-by in an annoyed ‘What the hell is that noise?’ kind of way. It’s a cheap black suitcase, with nothing going for it except that it’s big enough to carry my stock of frocks.

I come out through the imposing arch of Stables Market onto the busy Chalk Farm Road and I stand on the kerb, still undecided. Quick drink? Across the way, the lights in Cotton’s Rhum Shack are gleaming. It’s snug and inviting, located between a music shop and one selling white crockery. Right now, there’s a gap in the traffic and I’ve got the chance to dash across. Still, something makes me hesitate. It’s been a long day and I haven’t sold much so the case is heavy. If I turn right past the Lock and trundle my case along the towpath, I’ll be home. I can hang up the dresses, kick off my shoes, undo my fitted jacket and relax. Simple choice. Drink, or home?

Before I reach a decision, a woman coming along the pavement catches my eye. I see her now exactly as I did the first time we met, in a series of close-ups – the scarlet lips, the little Chanel suit, the black silk turban covering her dark hair, her sharp little face, faux pearls, a black patent handbag with intertwined Cs hanging from the crook of her elbow. She wears the outfit as naturally as if it’s her skin. It is the perfect fit. With the tick-tick-tick of her heels, she’s a combination of sound and vision – that confident, moneyed walk; chin tilted upwards, completely self-contained except for the way her eyes flick slyly towards me to gauge the effect she’s having.

I’ve imagined this moment for a long time.

I feel a surge of happiness and forget about the Rhum Shack. This is my chance to thank her, I decide, for the way she changed my life one day a few years ago.

I was very down at the time; stuck in a dark place. What turned me around was that she noticed me, a total stranger, when I thought I was invisible; she saw through my misery to the person I wanted to be; she told me in a few kind, well-chosen words how to be the person I could be.

I want her to see my transformation.

Transformation!

What a word.

It’s the best word in the English language.

She made me realise that we’re not fixed, rooted firmly in our inadequacies, but that we can change who we are whenever we choose; we can pick up the kaleidoscope, shake it and transform ourselves again and again. We can choose the way we face the world. We can choose the way the world sees us.

I’m smiling; I can’t help it. I wish I’d been the one who’d dressed her all up in black and white with those bright red lips.

As she gets closer she, in turn, is studying my outfit with equally blatant curiosity, from my shoes to my confidence-boosting slightly masculine Prince of Wales check jacket with shoulder pads and the nipped-in waist.

I lower my white sunglasses and my eyes meet hers.

She briefly raises one fine eyebrow and smiles at me approvingly.

I love that smile. It makes my day.

‘Darling, you startled me, you know!’ she says warmly. Dahlink, you stertled me! … Her accent is German or Austrian, strong and precise. ‘That suit! So chic! Suddenly, it’s 1949 again – I thought I was dead all of a sudden, bof! God knows, I’ve practised, but here?’ A train thunders over the bridge and she looks around, then winces and covers her ears at the trailing noise until it fades.

She folds her arms and looks at me again intently from head to foot, then works her way up once more – shoes, knees, skirt, jacket – and she nods her approval. ‘Perfect.’ She adds in a whisper from behind her slender hand, ‘Except for that suitcase, of course.’

This time around, she’s not looking at me with gentle compassion but with humour.

I look at my scruffy case and laugh. ‘Grim, isn’t it? But it’s practical.’

‘Oh, prektikel! Well then!’

Does she remember me? If she doesn’t, I’ll take that as a compliment because it’s a sign of how much I’ve changed.

Suddenly, her expression changes to one of alarm.

‘Oh! My bus is coming!’ she says. ‘Excuse me! Goodbye!’

The number twenty-four is coming up under the bridge and she spins around and hurries in her heels towards the bus stop, pearls jingling, her handbag swinging from the crook of her elbow. Waving at the driver, she reaches in her bag for her travel card. In her rush, she’s dropping her money. Coins are rolling over the pavement, spinning in all directions.

I crouch to gather them up for her. The number twenty-four bus comes alongside us, gusting warm fumes, and she hurries onto it.

‘Wait!’ I call, picking up as much of her cash as I can, but she doesn’t hear me, so I grab my case and step onto the bus just as the doors are closing. I’ve forgotten just how heavy my wheelie bag is. Before I can hoist it on board, the doors momentarily close on my arm.

As I yelp and let go, the driver opens the door again and a dark-haired, broad-shouldered guy in a pink floral shirt and jeans grabs the case by the handle before it falls to the ground. ‘It’s okay! I’ve got it!’ he says.

I sum him up at a glance. Not the fact that he’s good-looking and his eyes are deep blue; that’s just a quirk of nature and not a good indicator of character. What I notice is that his pink shirt is crisply ironed and he’s wearing tan leather shoes polished to a shine. For that reason, I immediately trust him.

‘Thank you!’ I say gratefully, then I hurry up the aisle to the woman in the Chanel suit and hand back her money.

She looks from me to her empty bag with great astonishment – what? Her cash has been trickling out of it? And I’ve been picking it up as it rolled away? ‘Ach, you are kindness itself!’ she says, kissing her fingers and scattering goodwill my way.

Good deed done, I go to get off the bus, when I suddenly realise that the man in the pink shirt hasn’t got on behind me. I wonder where he is and what he’s done with my suitcase.

And then I realise he’s taken it.

Not straight away – I’m a trusting sort of person and I have to double-check before it sinks in. First of all, I think wryly, ha ha, wouldn’t it be ironic if he’s run off with it when I’m here doing a good turn? And then I turn to the driver: ‘That man who had my bag, what did he do with it?’

The driver shrugs and puffs out his cheeks sympathetically then closes the doors.

‘Stop, I’m getting off,’ I say in a panic.

He opens the doors again, so I jump off the bus and look up and down the road with insane optimism as the bus pulls away.

The opportunistic thief has gone and stolen my case.

I lean against the high stone wall of Stables Market, taking deep breaths and pressing my heart back under my ribs.

This great, indescribable sense of loss comes over me, closing my throat with grief.

Gone. Stolen – my beautiful clothes; the clothes that are my livelihood and my dreams.

LOT 2

A Paul Smith gentleman’s pink slim-fit floral shirt, size medium.

Once the initial wave of shock passes, I straighten up and force myself to think about things rationally. I mean, that suitcase is so hideously noisy that no thief in his right mind would want to drag it for any distance. And who wants a load of old clothes, anyway? (Apart from me, obviously.)

First, because of the noise of my rickety case, I’m guessing the man wouldn’t have gone far. He’d probably nip down one of the residential side streets, out of sight, and find a quiet place to rummage through the contents of the bag, to see if there was anything in there worth keeping. And when he found that there wasn’t, I reassure myself, he’d dump it and walk away.

Guided by instinct and a bit of local knowledge, I head to Castlehaven Road, where there’s a large triangle of overgrown grass surrounded by wooden benches, known optimistically as The Gardens, which is usually deserted.

Today it’s busy. Circling each other on skateboards are three boys – for a hopeful but disappointing moment it sounds just like the wheels on my case. On one of the benches, two tanned and amiable drunks are making philosophical conversation through the medium of Carlsberg Special Brew lager.

The kids watch me suspiciously as I walk around the perimeter of the garden, eyes alert, holding firmly on to my handbag and visualising my scattered clothing fluttering in the long grass like injured birds (this is how sure I am I’ll find them).

But I don’t find them. On the path, the boys circle like sharks. I leave the gardens and walk slowly back to Chalk Farm Road, knowing I should keep on looking but also knowing in my heart how pointless it could be. The guy with my case could have headed straight for the towpath, or for the car park in the superstore, or down any of the other side streets, or he could have gone straight home. I think about my pathetic gratitude as he’d held my case for me while I triumphantly dashed onto the bus to hand the old lady her money back. That’s what you get for helping someone out, I reflect bitterly.

Back on Chalk Farm Road I look across towards the market. Miraculously, I suddenly see that pink shirt as he reappears right at the entrance to the Stables with my suitcase. ‘Hey!’ I yell. ‘Excuse me!’

‘Hey!’

We’re shouting across the traffic and waving our arms at each other.

‘Wait there!’ I’m dashing across in my pencil skirt, dodging cars – this is the way to cross a road in London: assertively. ‘My bag!’ I say warmly and with happy relief until I see he’s holding a small shaggy brown dog on a lead. I feel a familiar rush of fear and I keep a distance between us. I’ve got a thing about dogs.

‘Sorry,’ he explains. ‘I let go of the lead when I saw you struggling and my dog went back into the Stables to investigate the remains of someone’s burger. When I came back and I couldn’t see you, I kind of thought I’d better wait here, you know, as it was the last place we saw each other.’

I don’t know what it is about that sentence that melts my heart. It’s as if we’re old friends and that’s what we do, we come back to the last place we saw each other.

‘Thanks. Really. You don’t know what it means, to get my case back. It contains all of my best stock.’ My voice is wobbling with relief. He’s got a beautiful face. His nose is big and noble. He looks trustworthy and somehow sensitive, and his deep blue eyes never leave mine. The pink shirt sets off his tan. And he’s clearly kind. I grab the case, using it as a shield between the dog and me. ‘Thank you,’ I say to him again, because I’m still so relieved at getting it back.

‘My pleasure.’ He holds out his hand. ‘David Westwood.’

‘Really? Any relation to Vivienne?’ I ask, studying him with interest.

His blue eyes narrow as if he’s shortsighted and trying to focus. ‘Vivienne?’

‘She’s a fashion designer. Same surname.’

He laughs and shakes his head. ‘No, sorry. No relation.’

‘I’m Fern Banks.’ I jerk my head towards the entrance. ‘I work here.’

‘I guessed that when you talked about your stock.’ He looks interested. ‘So, how’s it working out for you?’

‘It’s early days,’ I reply; this is the reassuring fact that I hold on to in the quiet times.

‘I’ve got my name down for a stall.’

I give a shiver of serendipity. ‘Really? What are you selling?’

‘Light boxes.’ His gaze leaves mine for a moment. ‘I’m having a career change,’ he adds.

There’s something defensive about the way he says it that makes me glance up at him curiously, but I’m just happy that he’s not selling clothes; I’ve got enough competition as it is. And I’m still buzzing from getting my case back, so I say, ‘There’s a stall going next to mine. It’s small, though.’

‘Where exactly is it?’

‘It’s right next to the entrance to the covered market.’

He looks down at my case thoughtfully. ‘But there’s no storage, right?’

I shrug. ‘True.’ I feel a bit disappointed, even though it makes no difference to me whether he’s interested in the stall or not; I don’t know the guy and I’m just trying to be helpful. All the same, I really want him to take it. Nothing to do with his looks; anyway, I’m in a relationship. ‘My boyfriend thinks it’s a good spot because there’s plenty of through traffic,’ I hear myself say, just so we’re clear that my motives are entirely innocent. Then I inwardly cringe – first, because I sound like the kind of woman who needs reassurance from a man about her decisions and secondly, calling him ‘my boyfriend’ makes me sound adolescent.

Ideally, David Westwood would look devastated at the news I’m not single, but instead he nods and says seriously, ‘Through traffic is very important. Actually, I’m trying to get a place indoors, in the Market Hall.’

‘Oh, lovely!’ I say with deep insincerity.

‘My girlfriend, Gigi, says the atmosphere is really friendly in there. And of course it’s under cover.’

My girlfriend, Gigi. So here we are, two strangers making it absolutely clear that we’re all coupled up so that there can never be any misunderstanding about our motives.

I knew a Gigi at school and I’m just about to mention it, when I notice that the shaggy brown dog is getting restless. It gets to its feet and stretches before sniffing with great deliberation around his owner’s shoes. As if he can sense my gaze on him, he suddenly lifts his head and looks directly at me, his eyes alert under two blond eyebrows.

I look away quickly, feeling my heart rate rise. I try never to make eye contact with a dog, in case it sees it as a challenge and goes for me, so I wrap things up quickly, while I’ve still got the chance. ‘Well, David, thanks again for your good deed, minding my case,’ I say briskly. ‘I appreciate it.’

He looks bemused. ‘You’re welcome.’

The dog is tugging him towards Chalk Farm Tube, in the general direction of Cotton’s Rhum Shack. So that settles it. I’ll go the other way: straight home.

David Westwood raises his hand to wave goodbye; he walks away with his pink shirt flapping in the breeze.

I’m still looking at him, when he unexpectedly turns around.

‘Hey, Fern?’

‘What?’

‘I’d better watch myself, hadn’t I?’ he says, laughing. ‘You know what they say, right? No good deed ever goes unpunished.’

LOT 3

Black one-sleeved asymmetrical dress, rough stitching feature, labelled Comme des Garçons, Post Nuclear collection, 1980.

Home is along the Regent’s Canal towpath; a one-bedroom basement flat in Primrose Hill. The flat isn’t actually mine – my parents own it. It’s easy to get to, situated between the two Northern line stations of Camden Town and Chalk Farm. It’s a ten-minute walk along the canal from Camden Lock. It used to be my father’s pied-à-terre during the week and when he retired I moved in as a sort of tenant, to ‘look after the property’, as they put it, on a temporary basis until I save enough for a deposit for my own place. The emphasis is on the word temporary. However, I haven’t yet told them I’ve been fired from my dream job as personal stylist in a large department store, and that getting my own place has become an ever more distant and unlikely prospect.

In the meantime, I’m very grateful to live here.

The walk is beautiful in the early mornings; cyclists say hello, walkers smile, the air is fresh and the shadows of the bridges cast cool stripes across the towpath. The sky is filled with gulls shrieking like the sound of the harbour when the fishing boats come in. At night, though, it’s a different place – the smell of dope hangs in the air, empty lager tins bob on the glossy canal and the bridges are lit up with violet lights.

The decor in the flat is early 21st-century modern; this is my father’s taste: Barcelona chairs, glass console tables, a built-in glass wine rack and a flatscreen TV. The flat isn’t very big, but it has a brick-lined utility room that stretches under the pavement on the street, which I use as my walk-in wardrobe. The living area is divided between the kitchen at one end and the lounge at the other, with a hallway leading to the bathroom and bedroom. The bedroom is in an extension and looks out on a small L-shaped garden with raised decking and palm trees, which my father created in the new millennium when he heard on Gardeners’ Question Time that summer droughts would turn all gardens into deserts.

Since then it seems to have created its own microclimate. The hardy banana plants bear fruit, stubby little bananas that I’ve never been tempted to eat, then having thrown their energy into fruiting and fulfilling their mission, they give up and die and a new plant grows. All this happens without any help from me apart from a quick swaddle in the winter with gardening fleece.

The foliage is pretty to look out on and it’s fairly low maintenance. My father rings me up now and then to remind me to do the ‘brown-bitting’, as he calls it, which means cutting off the dead bits so that the palms look respectably green – it’s something I generally put off until just before my parents visit.

What else? I’ve got good neighbours. Above me lives Lucy Mills, an actor. The top floor is occasionally inhabited by a retired Welsh couple who travel a lot.

As well as my pitch in Camden Market, I sell clothes online. As a hobby it was fun, but as an actual source of income it’s not going that well, to be honest. The main problem is, I don’t like sending dresses out into a void. I like to know the person they’re going to; their shape, their colouring, their temperament.

The returns are a problem. Basically, women are now a different shape from what they used to be. And even though I write down the measurements of each garment along with a ‘will this fit you’ exact measurement guide, people really can’t be bothered to use a tape measure – does anyone even have a tape measure these days? I give the approximate equivalent dress size (this will roughly fit a size 10 or 12), but even if it does fit, that doesn’t mean it’ll necessarily suit a person. If shoppers like the look of something onscreen, they’ll give it a try and then send it back if it’s not suitable. This means that my income is worryingly unstable from day to day. It’s not a good feeling to be solvent at the beginning of the week and then over the next few days have to return the money and go back to square one.

And people aren’t always honest. Sometimes the clothes come back worn, or splashed with red wine, or smelling of cigarette smoke. And if I point this out in a phone call they’ll argue that I’ve ‘sold them as preowned so obviously … blah blah blah’. And that’s the reason for the one-star stroppy reviews that say if it had been possible to give less than one star they would have, because I was rude or reluctant to refund the money.

One of the main selling points of wearing vintage is that the piece is a one-off. It’s also one of the main drawbacks; the popular dresses are snapped up quickly and that’s another reason my ratings are low – it’s often down to disgruntled shoppers.

It’s hard work being self-employed, but since I lost my dream job as a personal stylist, this is my plan B. And that’s where I’m at now; trying to make it work. My long-term aim is to have a solid customer base of people to shop for. I love that feeling you get when you see a garment that brings to mind a person, when you find a dress that’s totally them, and all you want to do is reunite them.

In Camden Market at the weekends, it’s crazy. One month into my new venture, I’ve had a couple of really good days, which keep me going. A lot of gorgeous girls come through looking for something original to wear – model agency scouts find a lot of new faces in Camden – but the customers I like best are the ones who are shy and uncertain and who dress for comfort in safe colours: grey, beige, brown. They look warily at my stall as they hurry past, and then come back and try not to catch my eye. What keeps me going is when they find something and suddenly see themselves through new eyes. They are my dream customers.

Unfortunately, I don’t come across them very often.

I trundle the case up the horse ramp from the towpath and halfway along my street, I bump it down the steps to the basement.

The first thing I do is hang the dresses up in the utility room under the pavement. There’s no storage at my stall, which means I have to pack and unpack my stock every day.

While I’m getting on with this, vaguely thinking of my encounter with David Westwood, I hear myself saying ‘Any relation to Vivienne?’ in that cringy way and David Westwood laughing, ‘No. Sorry.’

And then my thoughts switch to the old woman wearing Chanel and red lipstick, model slim in her black-and-white Chanel suit, perfect in it, and that approving expression in her eyes when she saw me.

Unpacking a Comme des Garçons dress that still hasn’t sold on the stall after a month, I shake the creases out and put it on my mannequin, Dolly. With her moulded black hair and rosebud lips, Dolly seems particularly supercilious and unhelpful today. I bought her from Blustons in Kentish Town when it closed down. Blustons was famous for the Fifties-style showstopping red-and-white polka-dot halterneck dress in the window that Dolly modelled wonderfully for many years.

I move Dolly into the light and photograph her for the website. My phone rings and I pick up to my father, who tells me they are having dinner with the Bennetts and that they’ll be staying at the flat overnight. Oh joy!

First, this means I’ll be sleeping on the sofa. Secondly, I’ll have to tell them that I’ve lost my job – I’ve so far managed to put this off for a month by keeping our phone calls short.

There’s nothing wrong with my father; he’s a decent enough guy and he’d probably understand if I told him the whole story. But my mother’s a different matter. I’m always uncomfortable with her, never able to relax. She modelled in the Seventies, at the time when models dictated the popularity of women’s fashion, and my love of clothes has totally come from her. She never reached the worldwide popularity of models Jerry Hall and Christie Brinkley, but for a while she moved in the right circles, and the glitter and glamour of those times has never faded for her – she still has every copy of Elle, Cosmopolitan and Vogue magazines in which she featured.

When it became obvious in my teens that I was too short to be a fashion model – I overheard her tell a friend, regretfully, that I’d inherited my father’s looks and her brains – I thought it would please her if I studied fashion design. But at St Martin’s, the more I found out about the great designers, the more certain I was that I could never equal them. As a daughter, I’m an all-round disappointment and losing my job doesn’t help.

To take my mind off my worries, I call my boyfriend, Mick, who’s in Amsterdam with his band, just to say hello. It goes to voicemail, so I leave him a message to say hi.

Mick and I have been dating for nine months in a friends-with-benefits kind of way. We met at Bestival on the Isle of Wight. He’s got red hair and a beard that covers most of his very beautiful face. He’s a sound engineer and spends a lot of time travelling. Sometimes I meet up with him somewhere like Hamburg or Paris, and when he’s in London he stays over and we have fun together, but other than that, I don’t know where the relationship is heading, if anywhere. We both like it the way it is. He’s keen on the idea of free spirits; figuratively and literally – no commitment and drinks on the house. His job means that he’s not home a lot, but I don’t mind. Honestly, it suits me, too.

In a flurry of activity, I make up my bed for my parents with fresh linen, do a bit of desultory tidying, spray the place with Febreze, and then I go shopping for vodka, Worcestershire sauce, tomato juice and celery so I can make some Bloody Marys to welcome my parents with. It’s ‘their tipple’, as they put it, and because of the tomato juice element they knock it back as if it’s a health food, which is fine with me.

As a family we like each other a lot better after a drink.

I start watching television and around ten thirty, I give up on my welcoming committee duties and fall asleep.

I wake up as I hear them coming down the steps sometime later and listen to the key rattling in the lock. In my lowest moods I decide I’ll ask for that key back, ‘for a friend’, an excuse I’ve used before, but they seem to have a little stash of them in reserve in case I absentmindedly forget who owns the place.

With a wide smile of welcome, I jump to my feet and there’s my father in a Burberry trench coat, carrying an overnight bag and holding the door for my mother, who comes in with her cream hair blending with her fur-trimmed cream cape, fluttering, elegant and distant.

‘Hi! Hi! Come in!’ I say, even though they’re already very much inside.

I don’t recognise my mother at first. Without a shadow of a doubt, even despite my habit of scrutinising everyone, I would have passed her in the street.

My father has mentioned my mother’s ‘tweaks’, as he calls them, and I realise that one of them has involved filling the dimple in her chin. I have the very same dimple and now she’s got rid of hers … What does that mean? We both have the same wide mouth too, only hers is now poutier, even though she’d pouted perfectly adequately with the old one. And her eyes, which had been large and round, are smaller, as if her real face is sitting some distance behind the one she’s currently wearing. She has the eyeholes of Melania Trump.

She looks me up and down without a word, taking in my pencil skirt and white silk blouse. If she could have frowned, she would have. She recoils with a gasp when she sees Dolly. Overreacting is an affectation she’s developed.

‘You’ve still got that ugly old thing,’ she says.

I cover up Dolly’s ears. ‘Don’t offend her, she’ll come and get you in the night.’

My mother pretends not to hear.

‘Bloody Marys,’ I say cheerfully, sweeping my hand in the direction of the kitchen island as if I’m introducing them to each other.

‘Thank you, darling,’ my father says, putting his hands on my shoulders briefly in what passes as a hug.

‘It’s warm in here,’ my mother remarks in a troubled way. She looks around with the restlessness of discontent, fanning her strange and unfamiliar face. ‘Isn’t it warm?’

It isn’t, actually, because the heating went off at ten, but my mother’s menopausal, so I agree with her. ‘It’s been very sunny today and hot air sinks, doesn’t it?’