Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Wish List»

Praise for Sophia Money-Coutts

‘So funny. And the sex is amazing!’

Jilly Cooper

‘Hilariously funny – I couldn’t put it down’

Beth O’Leary

‘As fun and fizzy as a chilled glass of Prosecco’

Daily Express

‘Fast and furious, funny and fresh’

Daily Mail

‘Howlingly funny’

The Sunday Times

‘I started reading this book on the 3.48 from Waterloo and by 4.15 I was crying with laughter. Brilliant’

Sarah Morgan

‘Wonderfully rude’

Red

‘Fizzy, fun and some seriously saucy shenanigans’

Mail on Sunday

‘Perfect for fans of Jilly Cooper and Bridget Jones’

HELLO!

‘Fizzes with joy’

Metro

‘Surprisingly saucy and distractingly funny’

Grazia

‘Hilarious and uplifting’

Woman & Home

‘Does it earn its place in your beach bag? Absolutely’

Evening Standard

‘Cheerful, saucy and fun’

Sunday Mirror

‘Sexy and funny’

Closer

‘A hilariously funny debut’

Woman

‘Fans of Bridget Jones will love this romcom’

Sunday Express S Magazine

‘A thoroughly modern love story’

Woman’s Weekly

‘This saucy read is great sun-lounger fodder’

Heat

‘The perfect book to escape with’

The Sun

‘Bridget Jones’s Diary as interpreted by Julian Fellowes…a classy read’

Observer

‘Marvellous…a juicy read to romp through’

i

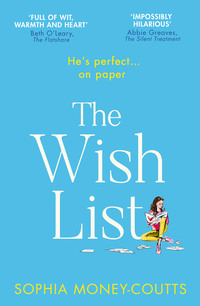

SOPHIA MONEY-COUTTS is a journalist and author who spent five years studying the British aristocracy while working as Features Director at Tatler. Prior to that she worked as a writer and an editor for the Evening Standard and the Daily Mail in London, and The National in Abu Dhabi. She’s a columnist for the Sunday Telegraph and the Evening Standard and often appears on radio and television channels talking about important topics such as Prince Harry’s wedding and the etiquette of the threesome. The Wish List is her third novel.

Also by Sophia Money-Coutts

The Plus One

What Happens Now?

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2020

Copyright © Sophia Money-Coutts 2020

Sophia Money-Coutts asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2020 ISBN: 9780008370558

Version 2020-07-15

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008370565

For Vix, my brave friend.

Contents

Cover

Praise

About the Author

Also by Sophia Money-Coutts

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Acknowledgements

Extract

Prologue

Chapter One

About the Publisher

‘Be careful what you wish for, you may receive it.’

THE SORT OF THING YOUR GRANDMOTHER SAID BUT, ACTUALLY, IT’S ANONYMOUS.

THE LIST

LIKES CATS.

INTERESTING JOB. NOT GOLF-PLAYING INSURANCE BORE LIKE HUGO.

BOTTOM AND SEXUAL ATHLETICISM OF JAMES BOND.

NICE MOTHER.

NO POINTY SHOES.

NO HAWAIIAN SHIRTS.

NO UMBRELLAS.

READS BOOKS. NOT JUST SPORTS BIOGRAPHIES.

NO REVOLTING BATHROOM HABITS. E.G. SKID MARKS.

AMBITIOUS.

ADVENTUROUS.

GOOD MANNERS. E.G. SAYS THANK YOU IF SOMEONE HOLDS THE DOOR OPEN FOR HIM.

ISN’T OBSESSED WITH INSTAGRAM OR HIS PHONE.

FUNNY.

ACTUALLY TEXTS ME BACK.

DOESN’T MIND ABOUT MY COUNTING.

Chapter One

‘TWO, FOUR, SIX, EIGHT, ten …’ I muttered, taking the steps two at a time. Shit. Eleven steps. An odd number meant that dinner was going to be bad.

That absurd evening at Claridge’s was where it started. That was how the list came about. As the quietest member of my loud, combative family, I often dreaded dinner with them. But I suspected this evening would be especially painful, which was why I counted the steps from the Hyde Park underpass into the evening sunlight. It was a game I called Consequences. If there’d been an even number of steps, the dinner would be all right. It would pass without drama and prove my family could behave normally. But no, eleven bastard steps. That dinner was always going to be tricky.

Technically, it was a celebratory evening because Mia had become engaged to Hugo. My half-sister had agreed to marry a man with all the intelligence and sensitivity of a spatula and everyone was meant to be excited. Patricia, my stepmother, had almost spontaneously combusted with joy at the idea of her daughter marrying a man who wore a signet ring, drove a Mercedes, belonged to a Surrey golf club and earned over £200,000 a year working for an insurance firm called Wolf & Partners.

I was less excited. I knew why Mia had said yes. Everyone seemed to say yes these days. They said yes in private, on a beach or up a mountain, then rushed to tell their 652 closest friends on Instagram that they’d said yes, sometimes with the hashtag #ISaidYes to underline the point. A lunatic hashtag since nobody was ever going to put up a photo above the hashtag #ISaidNo, were they?

Mia had posted her picture from the terrace of an expensive Italian restaurant a week ago. The shot was mostly of her left hand in front of her chest so we could all see the diamond as big as an eyeball on her finger. Her nails were fuchsia, her blonde bob was brushed and her face was smooth with make-up designed to look natural but had, in fact, taken Mia over an hour to put on that morning – she’d found the engagement ring a month earlier in Hugo’s boxer shorts’ drawer and realized he was about to propose.

You could just see Hugo behind Mia in this picture, as if he was trying to photobomb his own engagement shot. Underneath, Mia hadn’t just written #ISaidYes, but also #sparkly, #dreamscometrue, #heputaringonit, #shinebrightlikeadiamond, #happytears, #togetherforever and, finally, just #love. I’d spent a good deal of time scowling at this picture, trying to decide which hashtag was the worst. Was referencing both Beyoncé and Rihanna in a social-media post designed to alert the world to your engagement something you had to do now? I was thirty-two, but nonsense like this made me feel 900 years old.

I shook my head again at the thought of those hashtags. My half-sisters and I were different. I’d always known that. Mia and Ruby had confidence, hair that did what it was told and an intricate understanding of which Kardashian sister was which. I had none of those things. Still, we’d grown up together and remained living together in our narrow childhood house in south London. They were closer to one another than they were to me, almost their own separate little gang of two. I minded this some days, when I heard them laughing in one another’s bedroom, or when they draped their legs over one another on our sofa in front of the TV while I always sat in a separate armchair. On better days, I told myself this was just biology. They were full sisters, I couldn’t compete with that. But, while it might not have been fully reciprocated, I loved them as if they were my full sisters and figured it was better to co-exist with their bad habits (wiping mascara on the towels, never putting a mug in the dishwasher, eating my yoghurt) rather than move somewhere else and risk flatmates that were even worse.

I never thought one of them could be so different that she’d decide to marry the most boring man in Britain. And yet here we were, all off to Claridge’s to say ‘Cheers!’ because Mia had declared that was where she wanted the wedding in less than four months’ time. It seemed quick, as if she wanted to lock Hugo down as fast as possible, but Mia said winter weddings were more ‘chic’ than summer weddings. She would have berries in her flower arrangement and mulled wine at the reception. Her head was full of these intricate details. She’d also already decided that Ruby and I would be her bridesmaids so I gloomily anticipated wearing something the colour of sick.

All of us were going to Claridge’s that night, apart from my father, that is, since he was the British ambassador to Argentina and for the past six years had lived in an Edwardian mansion in Buenos Aires. He couldn’t fly home for the dinner, he’d apologetically emailed me to explain, because he had a meeting with one of Argentina’s biggest soybean exporters.

If Dad was back, I’d be rolling along the pavement with a bounce. Although we emailed every couple of weeks (I’d update him on new history books; he’d send me back brief updates, mostly about the weather), I missed his physical presence and wished he was closer, more in my life. However, the soybean magnate took precedence and so, gathered that night would be me, the happy couple, Patricia and Ruby. So long as she showed up. Ruby – blessed with the cheekbones of Kate Moss and breasts of a Barbie doll – was a model. Or trying to be a model. She’d been signed to an agent for a few years but had only been cast in magazine adverts for washing powder and toothpaste. Recently she’d been asked by Senokot, the constipation brand, to star in a series of posters for the Tube but turned them down. ‘You’d never catch Kylie Jenner doing that, Flo,’ she’d declared in the kitchen at home.

Still, she thought of herself as a ‘creative artist’, which meant she seemed to operate on a different timescale to the rest of us, as if time was a bourgeois construct she didn’t need to bother with.

One Christmas, Ruby didn’t come home until long after we’d finished the turkey, by which point Patricia was halfway down a bottle of Bailey’s and demanding that Dad use one of his government contacts to find out where she was. This far-fetched idea was forgotten when Ruby waltzed through the door sometime after five, claiming that her phone battery had died, the buses weren’t working and her credit card had been stopped which, in turn, meant that her Uber account was frozen. ‘Oh my poor darling,’ Patricia had slurred, clasping Ruby to her chest. ‘We must get you another credit card. Henry? HENRY! Can you order Ruby another card?’

I shook my head again. Patricia would almost certainly overdo it that night, ordering bottle after bottle of champagne, and the only topic of conversation would be the wedding. At home in Kennington, there’d been little discussion of anything else since Mia returned from Puglia, flicking her engagement ring about the kitchen like a knuckle-duster. It was ‘the wedding’ this and ‘the wedding’ that, as if there’d never been a wedding in history before, nor would be after it. Should Ruby or I ever choose to get married ourselves, I imagined that Mia’s wedding would still be referred to as ‘the wedding’ in our family. Not that this was likely, I reminded myself.

Because although I was thirty-two and had two arms, two legs and a face with its features in vaguely the right places (I hated my thin upper lip), I’d never had a boyfriend. Never been in love. True, there’d been a five-week fling at Edinburgh when I’d fallen for a second-year history student called Rich. But I’d ruined this by being too keen. I’d assumed after our first night together that he was my boyfriend, not realizing that Rich thought otherwise. He kept sneaking into my halls at 2, 3 and 4 a.m. during those brief first weeks when I’d found myself bewitched by a man for the first time, but there was a Thursday evening not long afterwards when my friend Sarah said she’d seen him snogging another girl in the Three Witches. I plucked up the courage to text him about it and Rich replied ‘What are you, my wife?’ The pain was so intense and sharp I felt like a small child who’d stuck their finger into a flame. That was the end of Rich.

I’d had precisely three very short flings since, one-night stands really, although I didn’t realize they were one-night stands at the time. You don’t, do you? I thought each one might be the start of something. Perhaps this one would finally be my boyfriend? Or the next one? Or the one after that? But they never morphed into boyfriends and I never fell in love because, after sleeping with me, they never texted or called me back. I’d tried to pretend I didn’t care after that.

No point in boyfriends, I told myself, when newspapers and magazines were full of women grumbling about relationships. ‘Dear Suzy, my boyfriend wants me to talk dirty every time we have sex and I’ve run out of vocabulary. What do you advise?’ Or ‘Dear Suzy, my husband always puts the empty milk carton back into the fridge instead of the bin. Should I divorce him?’ If I ever wrote a letter like this, I would ask ‘Dear Suzy, I’m thirty-two and I’ve never been in love but I’m pretty happy with life, although I still live with my sisters and I have a couple of weird habits. Sometimes I think not having a boyfriend by my age makes me strange, but can you ever tell in advance if someone’s going to hurt you?’

I stopped on the pavement and looked up at the façade of Claridge’s for a quick pep talk. Listen up, Florence Fairfax, this is going to be a cheerful evening and you will smile throughout. You will not look as sombre as if you’re at your own funeral because your sister is marrying a man who judges others by their golf handicap. You will sound convincing when everyone clinks glasses. You will not count every mouthful. Get it together.

I glanced at my feet and realized I’d forgotten the heels I’d carried into work that morning in a plastic Boots bag and I’d have to wear my work shoes instead. Black, with velcro straps and a thick rubber sole, they were the sort of shoes you see advertised for elderly men in the back of Sunday supplements. I wore them because I spent all day on my feet working in a Chelsea bookshop. Who cared if I looked like an escapee from a retirement home? I was mostly behind the till or a table piled with hardbacks. Except now I had to attend Mia’s celebratory dinner at Claridge’s looking like someone who’d had a recent bunion operation and been issued a pair of orthopaedic shoes.

Hopefully nobody would notice. I smiled at the doorman standing beside the hotel entrance in his top hat and pushed through the revolving door into the lobby.

‘Florence darling, what on earth have you got on your feet?’ Patricia asked, loudly enough for several other tables to hear. Mia and Hugo were already there.

‘Sorry,’ I muttered, leaning down to kiss my stepmother on the cheek. ‘Left my other shoes in the shop.’

‘Well sit down quickly and nobody will see them,’ Patricia carried on, nodding at an empty chair. ‘I’ve ordered some champagne.’ She was a woman with birdlike features – hooked nose, beady eyes – who minded about the wrong shoes and the right champagne very much. Twenty-five years earlier, she’d joined the civil service as a secretary called Pat and observed that those who progressed quickest seemed to be in a secret club. They wore the same suits and had the same accents. They talked about tennis as if it was a religion, not just a sport. She very much wanted to be part of that club, so she saved up to buy a suit from Caroline Charles, upgraded from ‘Pat’ to ‘Patricia’ and stopped saying toilet. She clocked my father as a target. He was a grieving widower whose wife had recently been killed in a car crash and was talked of as a rising star in the department. Patricia moved in quickly. Marrying someone from this club would guarantee entry into it.

Within a year, Dad had proposed and she was living in our Kennington house. I was three and seemed to have observed these changes in my life in bewildered silence. Mia came along another year on, which meant I was bumped from my first-floor bedroom up a flight into a new room which overlooked the street. Ruby was born the year after that, and I ascended into the attic.

‘Hi, guys,’ I said, standing over Mia and Hugo. Their heads were both bent to the table; Mia was reading a brochure, Hugo was tapping at his phone.

‘Oh, I don’t know. We could have it in the French saloon but it can only seat 120 people. Hi, Flo,’ said Mia, glancing up and waving a hand in the air as if swatting a fly before looking back to her brochure.

I’d never liked ‘Flo’. It made me think of Tampax. I’d been christened Florence after my maternal grandmother, a thin, energetic Frenchwoman who lived in an old farmhouse outside Bordeaux surrounded by village cats and apricot trees. I’d spent long stretches of my summer holidays there when I was younger, bribed to pick up fallen fruit. If I collected several baskets a day, Grandmère poured me a glass of watered-down wine that evening. It had been our secret and I adored her for it, for treating me like a grown-up when nobody else seemed to, when nobody else would talk to me about Mum and I was scared that I’d forget her. If anyone had dared called Grandmère ‘Flo’, she would have sworn at them in French. She’d died when I was fifteen and I’d clung to my proper name ever since, as if it still linked me to those summers, although I’d long since given up correcting my sisters.

‘Hugo, say hello to Flo,’ added Mia.

‘Hullo, Flo,’ said Hugo, raising his head from his phone and smiling weakly before lowering his gaze to his screen again. Honestly, I’d met more interesting skirting boards. If he was physically attractive I might have understood, but he looked like a pencil in a suit: tall and gangly, with an overly gelled hairline that had started receding, carving out the shape of a large ‘M’ on his forehead.

I looked from Hugo’s head to the table before sitting down. Five place settings, two candlesticks and one fishbowl of white roses equalled eight, which was fine because that was an even number.

‘Where’s Ruby?’ I asked as a waiter appeared with a bottle of champagne and held it in front of Patricia.

Patricia nodded at him. ‘Very good. On her way from a casting, didn’t you say, Mia?’

‘She said she might be late but we should go ahead.’ Mia held up her champagne flute and watched as the waiter poured, then held it up for a toast.

‘Everyone ready?’ she said. ‘Here’s to me. And Hugo,’ she added quickly. ‘Here’s to us, and to the best wedding ever.’ She squealed and scrunched her face as if on the verge of ecstasy at the thought of herself in a white dress.

‘Darling, I couldn’t be prouder,’ said Patricia.

‘So exciting!’ I lied as we clinked glasses.

Hugo winced and patted his chest – he had weirdly thin fingers too – as he put his glass down on the table. ‘Mia, have you brought any Rennie with you? You know champagne always gives me heartburn.’

Ruby arrived an hour later when we were halfway through the main courses. ‘Sorry, they kept us all waiting,’ she said, interrupting a debate which had been running for fifteen minutes about whether Mia and Hugo should have a wedding cake made of cheese or a Sicilian lemon sponge by the East End baker who’d designed Prince Harry and Meghan’s cake.

‘Hi, guys, hi, Flo, hi, Mum,’ she added, dutifully circling the table and kissing each of us on the head before throwing herself in the seat next to me. ‘I could murder a drink.’

‘We were just discussing my cake,’ said Mia, a forkful of fish paused in the air.

‘Our cake,’ corrected Hugo.

‘Catch me up, what have I missed?’

‘What was your casting for?’ asked Patricia, who dreamed of Ruby modelling on the cover of Vogue so she could boast to her friends at bridge club.

‘A new campaign for cold sore cream.’ Ruby glanced up at a hovering waiter. ‘Could I have a vodka and tonic please? Slimline tonic.’ She turned back to the table. ‘And it was crap. I’m not doing it even if they ask me.’

Ruby never seemed to mind missing out on jobs. Castings came and went every week and she shrugged them off, convinced that her big cover moment would come along one day. It helped that she was twenty-six and still had a credit card bankrolled by our father.

‘Oh well,’ said Patricia. ‘What do you want to eat?’

‘Er…’ Ruby looked at our plates. Hugo was chewing a rib-eye; after a debate of several minutes over whether the fish was cooked in butter or oil, Patricia and Mia had opted for the sea bass with the thyme cream on the side; I was having chicken but had swapped the truffled mash for chips because I thought truffle smelled like the crotch of my gym leggings and why anyone would want to eat that was beyond me. Plus, I could count the chips as I ate them. I couldn’t handle very small food like peas or grains of rice because they were too fiddly to count. Chips were fine.

‘Whatever Florence is having please,’ said Ruby. ‘I’m desperate for a fag but…’ She gazed around the room, as if anyone else would be smoking.

‘Can we get back to the wedding?’ demanded Mia.

Ruby sat back in her chair. ‘Yes, sorry. What’s the plan?’

‘We’re having it here but I’m worried about numbers. Are you bringing anyone?’ Mia narrowed her eyes. ‘Do you want to bring Jasper?’

Jasper Montgomery was Ruby’s latest boyfriend, a rakish playboy and the son of a duke who was to inherit a castle in Yorkshire and thousands of acres. Patricia was thrilled; Mia had become less pleased about our sister’s posh new relationship as the weeks wore on because Jasper kept turning up at home unannounced, late and pissed, leaning on the doorbell until someone answered it, usually Mia, whereupon Jasper would tumble into our hallway.

‘How on earth do I know?’ Ruby replied. ‘The wedding’s not until Christmas. That’s…’ she counted by tapping her fingers on the table, ‘four months from now. I can’t predict where we’ll be then.’ She was as relaxed about relationships as she was about timing. And this nonchalance, combined with her freckles and long, chestnut-coloured curls (she’d once been told she resembled a ‘young Julia Roberts’ in her headshots), meant that men fell about her like skittles.

‘Flo, what about you?’ said Mia.

‘What d’you mean?’

‘Are you bringing anyone?’

‘To your wedding?’

‘Yes, obviously to my wedding. What else would we be talking about?’

‘Our wedding,’ said Hugo.

The question made me defensive. ‘Well I mean, no… I didn’t… I don’t… I can’t imagine who that would be, so…’

‘Florence, sweetheart, I’ve been thinking about this,’ interrupted Patricia, and my jaw froze, mid-chew. Patricia’s tone had become wheedling, the widow spider seducing her prey before the kill. ‘I think it’s high time you considered your love life. You’re thirty-two, darling. You really should have had a boyfriend by now. What will people think otherwise? Time waits for no man. Or woman, in this case.’

I swallowed. ‘Perhaps they’ll think I’m a lesbian, Patricia.’

‘Gracious me. Are you a les…? Are you one of those?’

I picked up a chip and dunked it in the silver pot of ketchup beside my plate. ‘No, sadly.’

Even though I’d spent years pretending I didn’t care that I’d never had a boyfriend, years telling myself it wasn’t very feminist to worry about such things, privately I did mind. Was it my flat chest? My size eight feet? My pale colouring, or the mole on my forehead that I tried to hide with my hair? Could men tell that I was so inexperienced? Did I emit an off-putting, sexless smell?

Deep down, of course I wanted to fall in love. Doesn’t everyone? I’d spent my teenage years ripping through romantic novels and dreamed of being as alluring as Scarlett O’Hara, with the sassy intelligence of Jo March and the porcelain delicacy of Daisy Buchanan. In reality, I was starting to feel more like Miss Havisham. But although I allowed myself to brood about this on dark Sunday nights, I never admitted as much out loud and I didn’t want to discuss it with my family. Especially when my sisters’ allure was so much greater than my own.

We’d lived as a trio for years. Dad was posted to Pakistan when I was eighteen. Five years later, the Foreign Office moved him to Argentina. That was when Patricia moved into a flat in South Kensington. She’d never liked our house in Kennington because she didn’t think the postcode was fashionable enough, so she persuaded Dad to take out another mortgage and buy her one somewhere else. Patricia insisted it was to allow Ruby, Mia and me to remain living at home but the truth was Patricia felt she deserved to live in a posh flat with thick carpets, expensive floral wallpaper and an SW7 postcode. She was the wife of an ambassador, after all, even if she spent most of her time in London. She visited Buenos Aires every couple of months and Dad flew back for the odd meeting, but they spent such long stretches of time apart I used to wonder how their relationship was a success. Over the years, I’d realized it thrived precisely because of the long periods away. If they lived together full-time, one of them would have murdered the other. Patricia was the highly strung neurotic who made everyone take their shoes off when visiting her flat; Dad was the stable rudder. She wanted a husband who could afford her weekly haircuts and dinners in expensive restaurants; he needed a woman willing to be the diplomatic wife when she did visit. Patricia never minded cutting the ribbon at the opening of a new textile factory or chatting up the wife of the soybean magnate. The South Kensington flat was stuffed with official photographs taken at these events.

Anyway, ever since Patricia moved out, boyfriends had arrived at our house more often than the postman. They were mostly Ruby’s but, before Hugo, Mia’s hit rate had also been high and I’d often come downstairs in the morning to find men called Rupert or Jeremy hunting for tea bags in the kitchen. The only man who made it into my room was ginger, had four legs and was called Marmalade – my 17-year-old cat.

‘But we do worry about you,’ breezed on Patricia, ‘so what I’ve decided is that you should go and see this woman I read about in the hairdresser in Posh! magazine – she’s got a funny name. Gwendolyn something. A love coach. Or guru. Can’t remember which. But apparently she’s brilliant.’

I squinted across the table. ‘A love coach? What do you mean?’

‘There’s no need to be embarrassed, darling. Think of her like a therapist but for relationships. You go along, talk to her about your situation and what you’re looking for, and she helps you work out all your funny little issues.’

‘What. Do. You. Mean?’ I repeated slowly, enunciating each word.

‘I just think it must be a bit lonely at your age, still being on your own when your sisters are getting married. Sort of… unnatural.’

‘Mum, hang on,’ interjected Ruby. ‘I’m not getting marr—’

Patricia held a hand up in the air, signalling that she wasn’t finished. ‘Don’t you want to meet someone, darling?’ she said, leaning towards me. ‘Don’t you want to find a lovely chap like Hugo and settle down?’