Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Red Address Book»

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Sofia Lundberg 2017

English Translation © Alice Menzies 2017

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket illustration © Shutterstock.com

Sofia Lundberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Alice Menzies asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this translation

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008277925

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2019 ISBN: 9780008277949

Version: 2021-03-30

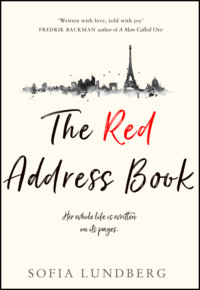

Praise for The Red Address Book:

‘Written with love, told with joy. Very easy to enjoy’

Fredrik Backman, New York Times bestselling author of A Man Called Ove

‘[A] Swedish romance steeped in memory and regret … The Red Address Book is just the sort of easy-reading tale that will inspire readers to pull up a comfy chair to the fire, grab a mug of cocoa and a box of tissues and get hygge with it’

New York Times Book Review

‘Wise and captivating, Lundberg’s novel offers clear-eyed insights into old age and the solace of memory’

People Magazine

‘With an ingenious hook and a glorious heroine, this book is a delicate balance of heartwarming and heartbreaking and a timely reminder to hold on to those you love in case they get away. Enchanting’

Veronica Henry

‘In this tender and heartfelt story, Sofia Lundberg offers a reminder that those we too easily dismiss, such as the elderly, have rich histories and lives that we can learn from … Completely engrossing from start to finish, The Red Address Book is a poignant tale of memory and how those things we carry in our heart work together to create our own life stories’

New York Journal of Books

‘In a reader’s lifetime, there are a few books that will be companions forever. For me, The Red Address Book is one of them. It will comfort you, and remind you of all the moments when you grabbed life with both hands. It is also an homage to the wisdom of women who have lived longer than most of us. One is never too old to learn that love is the only meaning of life – let’s listen to these women’

Nina George, author of The Little Paris Bookshop

‘Doris’s life story is magnetic, and it’s her strong personality and pearls of wisdom … that drive the book … Fans of Fredrik Backman will find much to like here’

Publishers Weekly

‘A warm and tender story about life, memories, and the power of love and friendship. A novel with heart and humor!’

Katarina Bivald, author of The Readers of Broken Wheel Recommend

‘The relationships [Doris] forms along the way, from the tortured gay artist who becomes a lifelong friend to the charismatic young man whose love drives Doris to battle enormous odds in an attempt to find him during WWII, are beautifully brought to life in this sweetly elegiac novel’

Booklist

‘Romantic … fabulous’

Lucy Dillon, author of Lost Dogs and Lonely Hearts

‘The Red Address Book is a love letter to the human heart. Full of tenderness and empathy, Lundberg has created more than just a novel – she has created a window into the soul’

Alyson Richman, author of The Lost Wife and The Velvet Hours

‘A charming, fragile romance’

Kirkus Reviews

‘Readers who enjoyed Eleanor Brown’s The Light of Paris or Nina George’s The Little French Bistro will delight in seeing Doris’s life unfold in this charming, tender tale’

Library Journal

Dedication

For Doris, heaven’s most beautiful angel You gave me air to breathe and wings to fly.

And for Oskar, my most precious treasure.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for The Red Address Book

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Epilogue

Keep Reading …

About the Author

About the Publisher

1

The saltshaker. The pillbox. The bowl of lozenges. The blood-pressure monitor in its oval plastic case. The magnifying glass and its red-bobbin-lace strap, taken from a Christmas curtain, tied in three fat knots. The phone with the extra-large numbers. The old red-leather address book, its bent corners revealing the yellowed paper within. She arranges everything carefully, in the middle of the kitchen table. They have to be lined up just so. No creases on the neatly ironed baby-blue linen tablecloth.

A moment of calm as she looks out at the street and the dreary weather. People rushing by, with and without umbrellas. The bare trees. The gravelly slush on the asphalt, water trickling through it.

A squirrel darts along a branch, and a flash of happiness twinkles in her eyes. She leans forward, following the blurry little creature’s movements carefully. Its bushy tail swings from side to side as it moves lithely between branches. Then it jumps down to the road and quickly disappears, heading off to new adventures.

It must almost be time to eat, she thinks, stroking her stomach. She picks up the magnifying glass and with a shaking hand raises it to her gold wristwatch. The numbers are still too small, and she has no choice but to give up. She clasps her hands calmly in her lap and closes her eyes for a moment, awaiting the familiar sound at the front door.

“Did you nod off, Doris?”

An excessively loud voice abruptly wakes her. She feels a hand on her shoulder, and sleepily tries to smile and nod at the young caregiver who is bending over her.

“I must have.” The words stick, and she clears her throat.

“Here, have some water.” The caregiver is quick to hold out a glass, and Doris takes a few sips.

“Thank you … Sorry, but I’ve forgotten your name.” It’s a new girl again. The old one left; she was going back to her studies.

“It’s me, Doris. Ulrika. How are you today?” she asks, but she doesn’t stop to listen to the answer.

Not that Doris gives one.

She quietly watches Ulrika’s hurried movements in the kitchen. Sees her take out the pepper and put the saltshaker back in the pantry. In her wake she leaves creases in the tablecloth.

“No extra salt, I’ve told you,” Ulrika says, with the tub of food in her hand. She gives Doris a stern look. Doris nods and sighs as Ulrika peels back the plastic wrap. Sauce, potatoes, fish, and peas, all mixed together, are tipped out onto a brown ceramic plate. Ulrika puts the plate in the microwave and turns the dial to two minutes. The machine starts up with a faint whirr, and the scent of fish slowly begins to drift through the apartment. While she waits, Ulrika starts to move Doris’s things: she stacks the newspapers and mail in a messy pile, takes the dishes out of the dishwasher.

“Is it cold out?” Doris turns back to the heavy drizzle. She can’t remember when she last set foot outside her door. It was summer. Or maybe spring.

“Yeah, ugh, winter’ll soon be here. The raindrops almost felt like tiny lumps of ice today. I’m glad I’ve got the car so I don’t have to walk. I found a space on your street, right outside the door. The parking’s actually much better in the suburbs, where I live. It’s hopeless here in town, but sometimes you get lucky.” The words stream from Ulrika’s mouth, then her voice becomes a faint hum. A pop song; Doris recognises it from the radio. Ulrika whirls away. Dusts the bedroom. Doris can hear her clattering around and hopes she doesn’t knock over the vase, the hand-painted one she’s so fond of.

When Ulrika returns, she is carrying a dress over one arm. It’s burgundy, wool, the one with bobbled arms and a thread hanging from the hem. Doris had tried to pull it loose the last time she wore the dress, but the pain in her back made it impossible to reach below her knees. She holds out a hand to catch it now, but grasps at thin air when Ulrika suddenly turns and drapes the dress over a chair. The caregiver comes back and starts to loosen Doris’s dressing gown. She gently pulls the arms free and Doris whimpers quietly, her bad back sending a wave of pain into her shoulders. It’s always there, day and night. A reminder of her age.

“I need you to stand up now. I’ll lift you on the count of three, OK?” Ulrika places an arm around her, helps her to her feet, and pulls the dressing gown away. Doris is left standing there, in the kitchen, in the cold light of day, naked but for her underwear. That needs changing too. She covers herself with one arm as her bra is unhooked. Her breasts fall loosely towards her stomach.

“Oh, you poor thing, you’re freezing! Come on, let’s get you to the bathroom.”

Ulrika takes her hand and Doris follows her with cautious, hesitant steps. She feels her breasts swing, clasps one arm tight against them. The bathroom is warmer, thanks to the under-floor heating beneath the tiles, and she kicks off her slippers and enjoys the warmth beneath the soles of her feet.

“Right, let’s get this dress on you. Lift your arms.”

She does as she is told, but she can raise her arms only to chest height. Ulrika struggles with the fabric and manages to pull the dress over Doris’s head. When Doris glances up at her, Ulrika smiles.

“Peekaboo! What a nice colour, it suits you. Would you like some lipstick as well? Maybe a bit of blusher on your cheeks?”

The makeup is set out on a little table by the sink. Ulrika holds up the lipstick, but Doris shakes her head and turns away.

“How long will the food be?” she asks on her way back to the kitchen.

“The food! Ah! What an idiot I am, I forgot all about it. I’ll have to heat it up again.”

Ulrika hurries to the microwave, opens the door and slams it shut again, turns the dial to one minute, and presses start. She pours some lingonberry juice into a glass and places the plate on the table. Doris wrinkles her nose when she sees the sludge, but hunger makes her lift the fork to her mouth.

Ulrika sits down across from her, with a cup in her hand. The hand-painted one, with the pink roses. The one Doris herself never uses, for fear of breaking it.

“Coffee, it’s liquid gold, it is,” Ulrika remarks. “Right?”

Doris nods, her eyes fixed on the cup.

Don’t drop it.

“Are you full?” Ulrika asks after they have been sitting in silence for some time. Doris nods and Ulrika gets up to clear away the plate. She comes back with steaming coffee in yet another cup. A dark blue one, from Höganäs.

“There you go. Now we can catch our breath for a moment, hmm?”

Ulrika smiles and sits down again.

“This weather, nothing but rain, rain, rain. It feels like it’s never ending.”

Doris is just about to reply, but Ulrika continues:

“I wonder if I sent any extra socks to the nursery. The little ones will probably get soaked today. Oh well, there must be spares they can borrow. Otherwise I’ll be picking up a grumpy sockless kid. Always this worrying about the kids. But I suppose you know what it’s like. How many children do you have?”

Doris shakes her head.

“Oh, none at all? You poor thing, so you never get any visitors? Have you never been married?”

The caregiver’s pushiness surprises Doris. These young women don’t usually ask this kind of question, at least not so bluntly, anyway.

“But you must have friends? Who come over occasionally? That looks thick enough, anyway.” She points to the address book on the table.

Doris doesn’t answer. She glances at the photo of Jenny. It’s in the hallway, but the caregiver has never even noticed it. Jenny, who is so far away and yet always so close in her thoughts.

“Well, listen,” Ulrika continues. “I’ve got to rush off. We can talk more next time.”

Ulrika loads the cups into the dishwasher, even the hand-painted one. Then she turns the machine on, gives the counter one last wipe with the dishcloth, and before Doris knows it, she’s out the door. Through the window, she watches Ulrika pull on her coat as she walks, and then climb into a little red car with the agency’s logo on the door. With shuffling steps, Doris makes her way to the dishwasher and pauses the wash. She pulls out the hand-painted cup, carefully rinses it, and then hides it at the very back of the cupboard, behind the deep dessert bowls. She checks from every angle. It’s no longer visible. Pleased, she sits back down at the kitchen table and smooths the tablecloth with her hands. Arranges everything carefully. The pillbox, the lozenges, the plastic case, the magnifying glass, and the phone are all back in their rightful places. When she reaches for the address book, her hand pauses, and she allows it to rest there. She hasn’t opened it in a long time, but now she lifts the cover and is met by a list of names on the first page. Most have been crossed out. In the margin, she has written it several times. One word. Dead.

The Red Address Book

A. ALM, ERIC

So many names pass by us in a lifetime. Have you ever thought about that, Jenny? All the names that come and go. That rip our hearts to pieces and make us shed tears. That become lovers or enemies. I leaf through my address book sometimes. It has become something like a map of my life, and I want to tell you a bit about it. So that you, who’ll be the only one who remembers me, will also remember my life. A kind of testament. I’ll give you my memories. They’re the most beautiful thing I have.

It was 1928. It was my birthday, and I had just turned ten. The minute I saw the parcel, I knew it contained something special. I could tell from the twinkle in Pappa’s eyes. Those dark eyes of his, usually so preoccupied, were eagerly awaiting my reaction. The present was wrapped in thin, beautiful tissue paper. I followed its texture with my fingertips. The delicate surface, the fibres coming together in a jumble of patterns. And then the ribbon: a thick red-silk ribbon. It was the most beautiful parcel I had ever seen.

“Open, open!” Agnes, my two-year-old sister, leaned eagerly over the dining table with both arms on the tablecloth, and received a mild scolding from our mother.

“Yes, open it now!” Even my father seemed impatient.

I stroked the ribbon with my thumb before pulling both ends and untying the bow. Inside was an address book, bound in shiny red leather, which smelled sharply of dye.

“You can collect all your friends in it.” Pappa smiled. “Everyone you meet during your life. In all the exciting places you’ll visit. So you don’t forget.”

He took the book from my hand and opened it. Beneath A, he had already written his own name. Eric Alm. Plus the address and phone number for his workshop. The number, which had recently been connected, the one he was so proud of. We still didn’t have a telephone at home.

He was a big man, my father. I don’t mean physically. Not at all. But at home there never seemed to be enough room for his thoughts. He seemed to be constantly floating out over the wider world, to unknown places. I often had the feeling that he didn’t really want to be at home with us. He didn’t enjoy the small things of everyday life. He was thirsty for knowledge, and he filled our home with books. I don’t remember him talking much, not even with my mother. He just sat there with his books. Sometimes I would crawl into his lap in the armchair. He never protested, just pushed me to the side so I didn’t get in the way of the letters and images that had caught his interest. He smelled sweet, like wood, and his hair was always covered with a thin layer of sawdust, which made it look grey. His hands were rough and cracked. Every night, he would smear them with Vaseline and wear thin cotton gloves as he slept.

My hands. I held them around his neck in a cautious embrace. We sat there in our own little world. I followed his mental journey as he turned the page. He read about different countries and cultures, stuck pins into a huge map of the world that he had nailed on the wall. As though they were places he had visited. One day, he said, one day he would head out into the world. And then he added numbers to the pins. Ones, twos, and threes. He was ordering the various locations, prioritising them. Maybe he was suited to life as an explorer?

If it hadn’t been for his father’s workshop. An inheritance to look after. A duty to fulfil. He obediently went to the workshop every morning, even after Grandpa died, to stand next to an apprentice in that drab space, with stacks of boards along each wall, surrounded by the sharp scent of turpentine and mineral spirits. My sister and I were usually allowed to watch only from the doorway. Outside, white roses climbed the dark-brown wooden walls. As their petals fell to the ground, we and the neighbourhood children would collect them and place them in bowls of water; we made our own perfume to splash on our necks.

I remember stacks of half-finished tables and chairs, sawdust and wood chippings everywhere. Tools on hooks on the wall; chisels, jigsaws, carpentry knives, hammers. Everything had its rightful place. And from his position behind the woodworking bench, my father, with a pencil tucked behind one ear and a thick apron of cracked brown leather, had a view over it all. He always worked until dark, whether it was summer or winter. Then he came home. Home to his armchair.

Pappa. His soul is still here, inside me, beside me. Beneath the pile of newspapers on the chair he made, with the rush seat my mother wove. All he wanted was to venture out into the world. And all he did was leave an impression within the four walls of his home. The highly crafted statuettes, the rocking chair he made for Mamma, with its elegantly ornate details. The wooden decorations he painstakingly carved by hand. The bookshelf where some of his books still stand. My father.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.