Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Ready, Steady, Go!: Swinging London and the Invention of Cool»

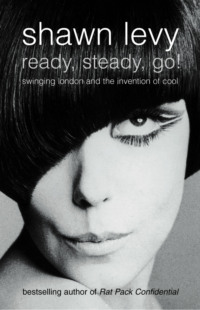

Ready, Steady, Go!

Swinging London and the Invention of Cool

Shawn Levy

For Mary, finally…

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

I

II

A Cloud of Pink Chiffon

The World Was Full of Chancers

Tugboat Terry

An Ordinary Person Couldn’t Do It

A Bit of Yankophilia

Strawberry Bob and the Mods

III

Nemperor

I Hadn’t Thought It Out Beyond That

The Box

Mick Doesn’t Like Women. He Never Has.

All the Young Stoned Harlequins

IV

We Are Not Worried About Petty Morals

The Road to Nowhere

‘This Ego I Had Nurtured Was Crushed’

‘Sort of Baudelaireish’

It’s Just Not Fun Anymore

V

Keep Reading

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

I

It happened to happen. All at the same time. Every day was a party. It was like a child who has been under the parents’ control, and all of a sudden on the eighteenth birthday, they say, ‘Here is the key to your Ferrari, here is the key to your house, here is your bank account, and now you can do whatever you like.’ It was enough to go mad! The new century started in 1960. After that, it’s only been perfecting what we started.

Alvaro Maccioni, restaurateur

Grey.

The air, the buildings, the clothing, the faces, the mood.

Britain in the mid-1950s was everything it had been for decades, even centuries: world power; sire of glorious intellectual, aesthetic and political traditions, gritty vanquisher of the Nazis, civilising docent to whippersnapper America, bastion of decency, decorum and the done thing.

But somehow, in sum, it was less.

Its colonies were demanding freedom and getting it; such unilateral forays into geopolitics as Suez were fiascos; its cuisine, architecture, popular entertainment, fashion and cinema succeeded only when mimicking continental or American models, as Matt Munro, Lonnie Donegan, Diana Dors and Norman Hartnell had done; it stood stubbornly outside a centralising Europe while shrinking alongside the US as standard bearer of Western values in a crystallising Cold War; it was a noncompetitor in the arms race, the space race and, more and more, the prestige race. Winston Churchill, hero of decades ago, sat in Parliament, and the spoor of antique manners lay thick in the air; it seemed a nation not so much in decline as left behind.

The States, France, Italy all felt modern. Rock music and the rise of the teenager as tastemaker made the American scene come on, naturally, loudest, while decadent, savvy, grown-up style made existential Paris and La Dolce Vita Rome meccas for both the international jet set and an emerging global bohemian underground. England by contrast was dowdy, rigid and, above all, unrelentingly grey, grey to its core.

In ‘53 – fully eight years after the war had ended – Britons were still eating rationed food, answering nature’s call in backyard privies, and making their daily way through cities that bore the deep scars of Luftwaffe bombing. Germany, Italy and Japan – the losers, mind you – were seeing their economies revitalise; France, which had been ravaged, was in recovery. But in Britain, the hard days still seemed alive. For many Britons, the mid-1950s were materially and psychologically a lot like the mid-1950s. It was, in the words of critic Kenneth Tynan, a ‘perpetual Dunkirk of the spirit’, made more bitter, perhaps, with the false glimpse of spring that was a young queen’s coronation.

Within a few years, however, that was to change. By 1956, the British economy had finally relaunched itself: key industries were denationalised by a conservative government; American multinationals were choosing Britain as the home base for their expansion into Europe; unemployment dipped, spiking the housing, automobile and durable goods markets; credit restrictions were eased, encouraging a boom in consumerism; and the value of property – particularly bombed-out inner-city sites – soared. In just three years, the English stock market more than doubled in value, and the pound rose sharply in currency markets.

Inevitably, as in America, prosperity led to complacency and nostalgia for a pre-war era that only in retrospect seemed golden. The mood, taken at large, was smug—or would have been, if smugness had been considered good form. The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, patting himself on the back in 1957, declared ‘You’ve never had it so good.’ And in many respects he was right—if you were of certain tastes and strains of breeding.

The common conception of big city excitement – women in long skirts, men in dinner jackets, dance band music, French cuisine, a Noël Coward play and a chauffeured Rolls – was just as it might have been in the 1920s. ‘London was kind of a grown-up town,’ remembered journalist Peter Evans. ‘It was an old man’s town. Nightclubs were where you went if you wanted to hear people playing the violin. There was nowhere to go. Even Soho closed early. There were drinking clubs, but they were private.’ There was nothing for young people,’ remembered fashion designer Mary Quant, ‘and no place to go and no sort of excitement.’

But as, again, in America, there were intimations of a burgeoning dissatisfaction with the status quo. And, perhaps because it had been beaten down for so long, or perhaps because its increasing marginalisation on the world stage liberated it from grave responsibilities, Britain seemed particularly fertile ground for this sort of seed.

At a pace that seemed wholly un-British, various strains of unofficial culture – defiant, anti-authoritarian, and hostile to such commonplaces of tradition as modesty, reserve, civility and politesse – were coalescing, not so much in unison as in parallel. Bohemians in Chelsea and Soho; radical leftists from the universities and in the media; teens with spending money, freedom and tastes of their own; these three groups would evolve and meld over the next few years to bring forth a dynamic that would centre in London and become a global standard. You could point to a few shops, pubs, coffee bars, theatres and dance halls where it all started; you could walk to all of them in a single fair day; and you would, in so doing, encompass an entire new world.

Ten years, maybe fifteen, maybe six.

London rose from a prim and fusty capital to the fashionable centre of the modern world and then retreated.

The ‘50s were Paris and Rome.

The ‘70s, California, Miami and New York.

But the ‘60s, that was Swinging London – the place where our modern world began.

Hardly any of the elements were unique: there had been bohemian revolutions and economic renaissances and new waves in the arts and popular culture and lifestyle before. There had even been other moments when youth dominated the scene: the Jazz Age of the ‘20s, the brief rock ‘n’ roll heyday of the ‘50s.

But in London for those few evanescent years it all came together: youth, pop music, fashion, celebrity, satire, crime, fine art, sexuality, scandal, theatre, cinema, drugs, media – the whole mad modern stew.

Decades later, the blend that was Swinging London has come to seem organic: whole empires would rise and fall on the mix, the bread and circuses and lifeblood of the contemporary mind; no one could imagine life without it or remember when things were different. Yet prior to the day when London hit full swing – some time, more or less, in August ‘63 – it hadn’t existed. Within three miles of Buckingham Palace in a few incredible years, we were all of us born.

It wasn’t youth culture that England invented – from James Dean to Levis to Elvis, that was America through and through – but where American official culture at the end of the ‘50s had effectively tamped down the expressive impulses of young people, England had embraced them as a way of emerging from decades, maybe centuries, of slumber. It let them grow, coalesce, strut. London was where youth culture finally cemented its hold on all forms of expression, and made itself loudly and exuberantly known. Youth, once something to endure, transformed in the span of a few years of British sensations into a valuable form of currency, the font of taste and fashion, the only age, seemingly, that mattered.

The Brits who created Swinging London were unique in their resilience, their ability to absorb and transform elements of American and continental culture, and the cocksureness with which they flaunted their invention of themselves. ‘Quite a tough bunch of kids made it through the war,’ reflected tailor Doug Hayward. And their toughness was one of their chief assets in their attack on tradition, as Barbara Hulanicki, who outfitted so many of the hip young girls at her Biba boutique, concurred: ‘The postwar babies had been deprived of nourishing protein in childhood and grew up into beautiful skinny people. A designer’s dream. It didn’t take much for them to look outstanding.’

It was as much a revolution in English society as any the island nation had ever experienced. ‘My generation,’ recalled the actor Sir Ian McKellen, ‘was brought up to think that you would peak in middle age. There was such a thing as the prime of life. And when you were secure financially and secure in what you believed in the world and what you could contribute to it, then your big years would come, and it would be in your 40s or your 50s. And suddenly it was all knocked on the head. Suddenly 40 was old.’

David Puttnam, then working in advertising, experienced it first-hand: ‘I had a little office that I had taken pains to make attractive, putting up the ads that I was responsible for. But I used to wear a white suit, and my hair was longish. And when they were showing a new client round the agency, invariably, they would kind of walk rather quickly past my room. Within a year, my room became a stopping-off point: “Look at this crazy young guy” – I looked about 12 – “and here’s his room with all his ads.” I moved literally within a year from being a liability to being an asset.’

Like all capital cities, London was used to hosting sensations, but this one wowed ‘em not only in the provinces, but everywhere on Earth. By the early ‘60s, the city positively overflowed with out-of-nowhere high energy. At night in London, anything could happen: you might attend a concert by a band of geniuses who would create music worth remembering for decades, or see a fortune come and go gambling at an elegant casino in Mayfair, or learn the Twist at a trendy discotheque near Piccadilly, or smoke pot at an after-hours Caribbean shebeen in Nörting Hill, or laugh out loud at the old fart prime minister being lampooned on a West End stage or at a nightclub in Soho.

And those were just the outward signs. If you looked harder you could find a bold, spirited and, crucially, employed generation of young people with education, access to birth control, freedom from mandatory military service – a new culture of morals and sensations being reinvented daily and no particular sense that the old ways were set in stone. These were English people who’d absorbed the sensibilities and attitudes of the French and the Italians and grafted them onto the materiality and energy of the Americans. They’d invented themselves as living works of art in a way no Britons had since Oscar Wilde.

More, too, than any free-thinkers in the history of England, this generation felt themselves unimpinged on by any of the caste conditioning that had divided them for centuries; their world would never truly be classless, as some of them liked to swear it was, but the illusion that it was was valuable, and there were specks of truth in it. If the American ‘60s were about breaking away from the establishment, England in the ‘60s was, at first at least, about joining in – finally. By mid-decade, a new aristocracy was in place: a popocracy, a hipoisie, a stratified pantheon of pop bands and actors and models and new-style entrepreneurs and a few tided and moneyed and privileged sorts who were hip enough to fit into the mix. It wasn’t a wide-open world, but it was perforated in ways it had never been before.

Streaming through the holes were foreigners eager to have a close-up look at things. London had suddenly become the hottest place in the world: New York and Paris and Los Angeles and Rome combined. Nowhere previously had such an agglomeration of globally notable talents combined at one time and with such a sense of common tenor – not to mention the inestimable advantage of tender age. For a few years, the most amazing thing in the world was to be British, creative and young.

‘The fashion and the art and everything was just exploding,’ said American hepcat Dennis Hopper, who made the trip over more than once to take part in the party. ‘Music. It was just amazing. The dance clubs and the jazz and these packed places, it was just incredible … I’ve never been anywhere that had that kind of impact on me, culturally. You can think of Haight-Ashbury and the hippie thing later, but this was more of a style and cultural explosion. It wasn’t the anti-, drop-out, tune-in whatever thing that we did. It was really about culture, painting, music, sculpture, fashion, clothes. I’d say for about five years, no one could touch them. They were dictating culture to the rest of the world.’

It changed, as it was bound to, as it was discovered and imitated and grew pleased with itself. By the middle of the decade, it wasn’t just a matter any longer of being talented and eager and lucky enough to be invited to sit at the adult table. The adult table itself was being shunned – along with everything that was eaten off it and what the diners wore and how they spoke to one another and what they smoked by the fire afterwards. The sharp, clean-shaven cool of the first phase of Swinging London was replaced by a defiant new mien – hairy and druggy and enamoured of strange fabrics and eccentricities acquired on foreign travels or in granny’s attic. By 1966 it was as if the young were so confident that they’d won that they didn’t need approval any longer. The most switched-on cat of 1963 could pass for straight; three years later, hip and square were different continents.

Things had become political – always a divisive step. And the cool new ways were being exported, too. The preferred new lifestyle of the young wasn’t quite built for London. Hippie may have looked swell in Hyde Park in July and August, but try it in January or November, making your way to some club through a downpour barefoot or in a peasant skirt. The aesthetic was far better suited to California or Majorca or the countryside. And, in fact, it was being practised and defined in such places, making the whole world seem hip when just a few years earlier only a handful of postal districts north of the Thames qualified. In 1963, a cool-looking person could only be from London; by 1969 standards, a person who looked with-it could be from anywhere.

Same with a pop record or a movie or a wild new outfit or haircut or art gallery or anything, really: London wasn’t alone any longer and it surely was no longer the centre or even the top. It was alongside New York and Los Angeles, Paris, and Rome and Berlin, and even Tokyo and Amsterdam and even, for a few minutes, Prague. The world had soaked up everything London could think up and was still thirsty, so it started brewing its own. In a real sense, London was losing because London had won. Its passing may have been inevitable – it had, ironically, helped cement the very notion of ephemerality in popular culture – but it was nevertheless a shame.

Yet for all the sweep of history and the pop artifacts and the indescribable meteorology of human taste, attitude and passion, Swinging London was built of individuals. People became icons because they did something first and uniquely. Everybody overlapped and partied together and slept and turned on and played at being geniuses together, but a few stood out and even symbolised the times – eminent Swinging Londoners, wearing their era like skin.

It would be possible, in fact, to explain the age by telling their stories.

David Bailey was one of the first on the scene, an East End stirrer and mixer and the most famous of the new breed of fashion photographers, who helped revolutionise the glossy magazines and popularise the new hairstyles, clothing and demeanour.

Vidal Sassoon, also from an East End background, but Jewish and, amazingly, a real warrior, who freed women from sitting under hairdryers and ascended into an unimaginable ether: flying to Hollywood to cut starlets’ hair and branding himself into an international trademark.

Mary Quant took a Peter Pan-ish impulse not to grow up and sicced her craft, inspiration and diligence on it, creating a new kind of women’s fashion that spoke to the rapidly expanding notions of what it meant to be cool, free and young.

Terence Stamp, another one from the stereotypical Cockney poverty, wound up winning acting prizes, with his face on magazine covers, the most beautiful women in the world on his arm and a home among peers and prime ministers in the most prestigious part of London – and then wandered out the back door of the decade into spiritual quest.

Brian Epstein failed miserably at everything until he helped create the greatest entertainment sensation of the century while warring internally against the self-doubts he’d borne his whole life.

Mick Jagger, a suburban boy with a bourgeois upbringing, could mimic whatever he wished: black American music, the stage manner of raunchy female performers, the go-go mentality of rising pop bands, the chic manners of slumming aristocrats, and the arcane sexual and narcotic practices of bohemians both native and exotic – a quiver of cannily selected arrows that let him survive the decade unscathed while the road behind him was littered with the corpses of friends.

Robert Fraser, who had every tool that traditional English life could offer a man – birth, schooling, military appointment, connections, polish, bearing – was cursed with a restless imagination and a decadent streak that led him into art-dealing and sensational living that brought him down.

Lay these lives alongside one another, bang them together, hold them up to the light, and you could open an entire time.

You could see how people lived and rose and changed and stumbled and faded or kept on rising until they disappeared into the sun.

You could see how people made a glory of their day or their days into a glorious apotheosis of themselves.

You could hear the music, feel the energy, see the Paisley and the op art and the melting, swirling colours.

You could go back to Swinging London.

II

A Cloud of Pink Chiffon

The story of David Bailey’s early life and career would come to sound a cliché: scruffy working-class boy aspires to a field normally reserved for the posh and sets the world on its ear without bending his personality to fit the long-established model. But like the jokes in Shakespeare or the Marx Brothers, it was only familiar because it was repeated so often from the original. All the pop stars, actors, dressmakers, haircutters, club owners, scenesters, satirists and boy tycoons who exploded on the London scene in the early ‘60s did so after Bailey, often in his mould and almost always in front of his camera.

Before Mod and the Beat Boom, before Carnaby Street and the swinging hotspots of Soho and Chelsea, before, indeed, sex and drugs and most of rock ‘n’ roll, there were the laddish young photographers from the East: Bailey, Brian Duffy and Terence Donovan – ‘The Terrible Three’, in the affectionate phrase of Cecil Beaton, an iconoclastic snapper of another age whose approval of the new lot made it that much easier for them to barge in on what had been a very exclusive and sedate party.

The trio – and a few others who came along in the rush – dressed and spoke and carried on as no important photographers ever had, not even in the putatively wide-open worlds of fashion magazines and photojournalism. They spoke like smart alecks and ruffians, they flaunted their high salaries and the Rolls-Royces they flashed around in, they slept with the beautiful women who modelled for them, they employed new cameras and technologies to break fertile ground in portraiture and fashion shoots. They were superstars from a world that had previously been invisible, perhaps with reason. ‘Before ‘60,’ Duffy famously said, ‘a fashion photographer was somebody tall, thin and camp. But we three are different: short, fat and heterosexual.’

Duffy could enjoy such self-deprecating boasts because, recalled Dick Fontaine, who tried to make a documentary about the trio, ‘He was really the kind of architect of the guerrilla warfare on those who control the fashion industry and the press.’

But it was Bailey who would bring the group their fame and glory. Bailey was the first bright shiny star of the ‘60s – a subject of jealous gossip, an inspiration in fashion, speech and behaviour, an exemplar of getting ahead in a glamorous world and, incidentally, the great, lasting chronicler of his day.

David Bailey was born on 2 January 1938 in Leytonstone, east of the East End, a block over, he always liked to brag, from the street where Alfred Hitchcock was born. When Bailey was three, the family home took a hit from a Nazi bomb, and they relocated to Heigham Road, East Ham, where Bailey and his younger sister, Thelma, were raised.

Their father, Herbert, was a tailor’s cutter and a flash character who dressed nattily, ran around on his wife and liked to have a roll of fivers to hand; his wife, Gladys, kept house but also worked as a machinist, especially after Bert finally left her. The family wasn’t rich, but they were comfortable – they were among the first people in their street to have a telephone and TV set, and Bailey was made to dress smartly, to his chagrin ('What chance have you got in a punch-up in East Ham wearing sandals?’ he later sighed). But they weren’t entirely free of money worries, and one of their ways of dealing with them was, to Bailey, a blessing: ‘In the winter,’ he recalled, the family ‘would take bread-and-jam sandwiches and go to the cinema every night because in those days it was cheaper to go to the cinema than to put on the gas fire. I’ll bet I saw seven or eight movies a week.’

Bailey fell, predictably enough, under the spell of rugged (and mainly American) actors at around the same time that his parents’ marriage was foundering. But Bert Bailey was nonetheless a little worried about his son’s fancy for birdwatching and natural history, which loves led the boy into vegetarianism. ‘My father thought I was fucking queer,’ Bailey said, ‘but queer didn’t mean homosexual. In those days it just meant a bit of an oddball.’

Part of Bailey’s ‘queerness’ was taking and developing photos of birds – he preferred the latter process, as it involved playing with chemicals. Even so he didn’t think of taking pictures as a career ambition – ‘photography was something you did once a year on Margate beach’—and he had enough on his hands at school, where his learning disabilities (undiagnosed at the time) made for a hellish routine. ‘I can’t read and write,’ Bailey said. ‘Dysgraphia, dyslexia – I’ve got them all. I went to the silly class – the school for idiots – and they used to cane me when I couldn’t spell. It was quite tough knowing that you’re smart and thinking you’re an idiot.’

At 15, he dropped out of school altogether and started a series of unpromising jobs: copy boy at the Fleet Street offices of the Yorkshire Post, carpet salesman, shoe salesman, window dresser, time-and-motion man at the tailoring firm where his father worked, and debt collector. He developed a taste for jazz and spent nights checking out the music and women at the handful of venues the East End offered someone his age. His musical interests were underscored in his oft-quoted quip about his roots: ‘You had two ways of getting out in the ‘50s – you were either a boxer or a jazz musician.’ So perhaps it was inevitable that he followed an artistic muse, especially as he quickly learned how ill-suited he was to make a living with his fists: ‘The Krays, the Barking Boys and the Canning Town Boys were the three gangs at the time,’ Bailey remembered. ‘They weren’t gangsters, they were just hooligans. They just went around beating people up if you looked at them wrong in a dance hall. I got beat up by the Barking Boys because I danced with one of their girlfriends. They left me in the doorway of Times Furnishing.’

Bailey’s aimlessness was finally punctured by the call-up: in the spring of 1956, he was ordered to report for a physical for the National Service. He tried to duck it – he stayed up two nights straight and consumed a huge quantity of nutmeg (‘Someone said it made your heart go faster’), but it didn’t work. He might have requested assignment to a photographic unit, but that meant a longer hitch than he was ready to sign for. In August, he reported for basic training in the Royal Air Force, and by December he was stationed in Singapore as a first-level aircraftman with duties such as helping to keep planes flight-ready and standing guard on funeral drill.

On the whole, Private Bailey found the situation pleasant enough. ‘I had a good time in the National Service,’ he confessed years later. ‘I hate to sound like a right-wing middle-aged man, but I think it was very good for me.’ There were, he admitted, drawbacks: 'The snobbery! They had a toilet for privates, a toilet for sergeants and a toilet for commissioned officers, as if all our arses were different. It made me angry, the way we were treated, almost like a slave. You were dirt compared with an officer.’

Indeed, it was a run-in with an officer that would prove pivotal in shaping Bailey’s future. He was still on his jazz kick – his ‘Chet Baker phase’, as he later deemed it – and trying to teach himself to play the trumpet. But when an officer borrowed his horn and failed to return it, he was forced to seek another creative outlet. Cameras could be gotten cheap in Singapore, so Bailey – who’d been as enamoured of the photos of Baker on the trumpeter’s album jackets as of the playing inside – bought a knock-off Rolleiflex. He was sufficiently hard up for money that he had to pawn the camera every time he wanted to pay for developing his film, but he had caught the bug.

The camera suited Bailey’s growing bohemianism. He had begun to read, and where his barracks mates had pin-up girls hung over their beds, he had a reproduction of a Picasso portrait of Dora Maar. His pretensions didn’t go unnoticed. ‘I did used to get into fights,’ he said. ‘But because I was from the East End I could look after myself. I also had the best-looking WAAF as my girlfriend, so they knew I wasn’t gay.’

When he was demobbed in August 1958, Bailey acquired a Canon rangefinger camera and the ambition to make a living with it. He applied to the London College of Printing but was rejected because he’d dropped out of school. Instead, he wound up working as a second assistant to photographer David Olins at his studio in Charlotte Mews in the West End. He became a glorified gofer (not even glorified, actually, at £3 10s a week) and was therefore delighted a few months later to be called to an interview at the studio of John French, a somewhat better-known name and a man who had a reputation for nurturing his assistants’ careers.

French, then in his early 50s, was the epitome of the fashion photographer and portraitist of the era: exquisitely attired, fastidious, posh, and gay (although, as it happened, married). ‘John French looked,’ Bailey remembered, ‘like Fred Astaire. “David,” he said, “do you know about incandescent light and strobe? Do you know how to load a 10×8 film pack?” I said yes to everything he asked and he gave me the job, but, at that time, I didn’t even known what a strobe was. We became friends and after six o’clock Mr French became John. One night I asked him why he gave me the job. “Well, you know, David,” he said, “I liked the way you dressed.” Six months later everyone thought we were having an affair, but in fact, although we were fond of each other, we never got it on.’

In fact, French – ‘a screaming queen who fancied East End boys’, according to documentarian Dick Fontaine – was the first person to really recognise something special in Bailey. Partly it was his bohemian style – Cuban-heeled boots, jeans, leather jacket and hair over the ears – all before the Beatles had been heard of; partly it was his aptitude for the craft. French liked to compare his young protégé to the unnamed hero of Colin Maclnnes’s cult novel about bohemian London, Absolute Beginners (a savvy insight) and he was perfectly willing, as he had with many previous disciples, to see Bailey get ahead in his own work.

‘He was an incredibly decent type of man,’ Bailey would say of his mentor after French died in 1966. ‘I don’t think he was very good as a photographer, but he had a good attitude. His photography sort of slowed me down a bit, because I had to break away from his way of doing things, but I benefited from his attitude.’