Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «If You Go Down to the Woods: The most powerful and emotional debut thriller of 2018!»

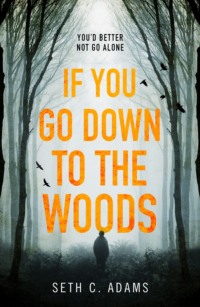

If You Go Down to the Woods

SETH C. ADAMS

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

Copyright

KillerReads

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Adam Contreras 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com

Adam Contreras asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008280246

Version: 2018-01-24

Dedication

This story is about family, friends, and a good dog (which qualifies as both!), and so it is to these I dedicate the novel.

To Mom and Dad, for allowing—and encouraging—their weird son to read whatever he wanted.

To my own group of Outsiders that enriched my life throughout the school years. We may have never fought off assassins and gangsters, but sometimes just surviving life is a fight all its own, made a bit easier with a good group of pals.

To Sheba, Rusty, Outlaw, and Banjo: great dogs, and even better friends.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: The Promise

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two: The Car and the Collector

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three: This is the Night

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

1.

This is the night. These are the times.

I heard these words for the first time from a killer the summer I met the Outsiders’ Club. Years passed before I finally understood them and, by then, everyone—my friends, my family, my dog—were long gone: some to the dirt that eventually claims us all, others to the remote reaches of time and memory.

The promise the Outsiders’ Club made to each other had a part to play in the way things went down. No doubt about it. But much of it was just life itself, and things beyond our control. Yet I still wonder how it all would have turned out had other choices been made, different roads taken. This is called regret, and it’s very important you listen to what it says.

In my case, the long trail of dead that summer demands it.

Sometimes life’s fucked up that way. Sometimes the darkness lingers.

Here’s what happened.

2.

My family moved to Payne, Arizona when I was thirteen. My dad, John Hayworth, got a job as the manager of a Barnes & Noble bookstore, and we moved there from Southern California. Mom, a college-educated woman, decided that being a mother was far more important than searching for meaning in the writing of centuries-dead English novelists, and wholeheartedly supported the move. For those prematurely crying sexism, this was a two-way street kind of respect: Dad supported her, offered to be the stay-at-home parent as she climbed the ranks of prestige in academia. But I think Mom saw more value in passing on her passion for the written word to her children, reading us stories snuggled in our beds or on the sofa, than lecturing youth enrolled in electives, packed like sardines in large lecture halls.

My sister and I had to leave our friends, and though I was sad about some of the people I left behind, I also saw it as something of an adventure. Sarah, on the other hand, sixteen going on retarded, acted like she was saying goodbye to her whole life and every shot at happiness. She had some greasy-haired boyfriend that she was leaving behind, some young stud who thought wearing a leather jacket and slicking his hair back with a few pounds of hair gel made him some sort of James Dean. I thought it made him look like he’d melted butter and greased his head with it.

I told him so once.

He flipped me off.

I laughed at him and gave the old jerk-me-off sign language.

Sarah didn’t talk to me for a week after that. That was fine by me. Likewise, I tolerated her like a bothersome rash: it was there, it caused discomfort, but there wasn’t much you could do except live through it.

Looking back, I realize she wasn’t all that bad. I might even go so far as to say she was a good older sister in some ways. But try telling that to a thirteen-year-old boy, just learning the mysteries of girls and the smaller head in his pants, living in a small house with an older sister who liked barging into his room at any hour to bestow upon him the gifts of noogies, wedgies, and wet willies.

Last, but most definitely not least, I can’t forget my dog, Bandit, a German shepherd mix, with some of that mix maybe being wolf. White and gray and silent like some sort of ghost dog from an Indian legend, Bandit was large and stoic and loyal, obedient but obstinate in his own way, and never left my side if I allowed it. He slept in my bed, his loose hairs finding their way up my nose and in my mouth, and my sinuses suffered for it for years. Dad invariably scolded me about keeping that dog in my bed, but there’s something about dogs and boys, how they’re meant to be, and the years that dog spent with me—warm friend, heartbeats lulling each other to sleep on cold nights—and I don’t regret a day.

I remember the long drive through the desert highways to our new home. Hills that seemed to roll to forever in every direction. Sparse trees like stubble on the earth. Mom and Dad took turns driving so the other could rest. Sarah dozed across the seat from me in the back or stared pathetically out the window, a hand under her chin in melodramatic melancholy. Bandit sat or stood on the seat between us, going from window to window, paws on my lap to try to get a good sniff of what was passing us by, and I’d let him, until a stray paw stepped on my nuts, then I’d push him away. I stared out the car windows as well, watched the fiery skies of morning give way to the bruise-blue of afternoon, and remember thinking that though things were changing it might not be all that bad.

I was a simple kid to please. All I needed for contentment and happiness were a good book, some comics, and horror movies, and with Dad a manager at a Barnes & Noble I’d have those things in spades. A whole summer of lazy afternoons, curled in my bed in my room or on a chair on the porch or sprawled on the grass of the lawn, seemed like the superfluous joys of heaven.

The new house didn’t let me down in that regard. I’d seen pictures of it my parents had taken on a trip they’d made earlier in the year to see the property, but the still images didn’t do the majesty of the place justice.

As Dad turned the station wagon off the highway and onto a country residential sprawl of a road, I found myself leaning forward in anticipation. When we turned the last bend, and I recognized the house from the pictures, I alternately gripped the seat and wiped my palms on my jeans.

It sat on two acres of well-manicured land, carpeted by grass the green of emerald dreams. The whole place was fenced by chain-link, which to some might have made it seem vaguely white-trashy in nature, but to my boy’s mind made it seem a secluded fort of a kind. The porch had an overhanging awning and was enclosed by a screen mesh that let you see out but made it hard for others to see in, so all they saw were dark shadows and silhouettes. There was a pool in the back, dry and mossy in places, the cement lining cracked in others, that Dad promised to have repaired and filled soon.

Apple trees dotted the yard, and in the summer the branches were in full bloom and heavy with their juicy burden. The lawn was speckled with the fallen fruit, and as soon as the car braked to a stop with a little cloud of dust, I leapt out, dashed across the grass, scooped up an apple and let it fly. Perhaps thinking I’d filched one of his tennis balls from the trunk without him seeing, Bandit darted out of the car behind me, and charged after the green sphere. Finding it among the litter of others, he spun around in a frenzy, confused and smiling and uncertain by the mass of apples. To his dog’s brain, they must have seemed the sweet, multitudinous edible balls of some canine paradise.

“Come on, Joey,” Dad called after us, stepping out from behind the wheel and stretching. “There’ll be time for that later. We got work to do.”

The moving trucks arrived well before us, and the sweat-drenched men had our boxes ready, piled high in totem-like stacks along the porch. Motioning for Bandit to follow, we bounded up the porch steps together. I found the growing stack of boxes with my name written on them in large Sharpie marker letters and began taking them to my new room.

The work went on for hours, and Dad had a cooler set out on the porch, along with plastic chairs, and we all took breaks when we felt like it. Pop open a soda, cram one of Mom’s sandwiches in my mouth, and for me it was relaxing. Work, yes, but also fun in a way as I looked out across the desert town in the distance. At times my gaze would drift over to the faraway woods bordering the township, and that dense, mysterious greenery seemed to call to me and Bandit.

Slowly, afternoon crawled into the first evening, purple-black over our new home. My bed set up, having unloaded several boxes of books with many more to go, I sat in bed, the window beside it open. The cool desert breeze drifted in and stirred things with a whisper. A volume of Ray Bradbury stories was open in my lap, propped up by a pillow. Bandit was at my feet, large and furry and kicking his feet occasionally with rabbit filled doggie dreams.

The act of reading usually soothing, I had trouble keeping my mind on the pages before me. My gaze kept drifting to the walls and contours of the room. Realizing I’d spent the last fifteen minutes or so on the same page, I finally gave up and set the book aside.

The room was painted an earthy brown and seemed spacious and snug at the same time. I had my own TV, a gift from last Christmas, and I knew exactly where I wanted it to go. Mom promised she’d call the cable company “tomorrow,” and I dreamt of late-night horror marathons. I had boxes of books and comic books yet to be unpacked, and imagined the bookshelves that would line the walls like sentinel soldiers.

There were the other magazines that I had also, buried among my books and filed secretly in between the comics. Magazines of a certain nature all boys must look through at some point, cracking the covers open ever so slightly, ever so slowly, as if lifting the lid to a treasure chest. Treasures they were, too, and I thought of being able to look at these at my leisure in the privacy of my new room.

Then the door to my room swung open and there she was, that rash that wouldn’t go away, a look of demented sisterly pleasure on her face.

“You know what I’m here for,” she said.

And I said: “Yeah, but I’m all out of Ugly-Be-Gone.”

When she charged across the room, I scooped up the book to try and defend myself, and the Queen of Noogies sent me to sleep with bruises and one bastard of a headache.

And the tired realization that some things would never change.

3.

I met Fat Bobby first. His real name was Bobby Templeton, but fat he was and knew it, seemed to despondently accept it, and so Fat Bobby he became.

Now I don’t know about God or anything like that. I guess I’ve asked myself the Big Questions like just about anyone else has in their life at some point or another, but I guess my brain is too small for the Big Answers. There isn’t much in this life that makes sense to me, but one thing I’m pretty sure of is that there isn’t any such thing as coincidence. It seems that how one thing leads to another and that to another, so that there’s a whole series of events that gain momentum and become inevitable, is a natural consequence of cause and effect, and there isn’t anything coincidental or accidental about it.

I think Fat Bobby was the first in just such a chain of events. I think on how it all ended, the pain and the loss and the misery, and wonder how it all would have been different if I had just passed on by that fat kid in the woods.

But then there wouldn’t have come the other things: the friendship, the trust, the laughter.

All things good in this haphazard mess we call life.

* * *

On Dad’s first day at the store, I woke up early, thinking I’d cut through the woods and walk into town, maybe check out the local comic book shop, perhaps pay Dad a visit. Lazily excited, I rolled out of bed and stumbled my way to the bathroom across the hall, Bandit following. Starting the water in the shower stall, I waited for it to warm, stripped, and climbed in. Bandit watched with a perplexed expression from the throw rug in the center of the bathroom’s tiled floor, as if he wondered why he was excluded from this splashy fun.

After throwing on jeans and a T-shirt, hair still wet from the shower, I raced downstairs. Mom was preparing breakfast, something sizzling tantalizingly in a pan atop the stove. She asked if I wanted some bacon and eggs, and though I was sorely tempted by the smells, I told her my plans and said I’d have Dad get me something from the bookstore cafe. A mild scowl told me what she thought of the nutritional value of a cafe breakfast, but Mom didn’t object.

“Just make sure if you’re going down to the woods,” she said, “don’t go alone. Take Bandit with you.”

I hardly needed her advice on this, and neither did Bandit, prancing so close behind me that if I stopped abruptly he’d end up nose first in my backside. Out on the porch, Bandit at my heels, Mom called after me and asked when I’d be back. Down the porch and into the yard, I yelled back an “I don’t know!” and continued down the road.

Our dirt road led to the highway, which in turn led into Payne proper, but as I walked my eyes drifted to the nearby woods. I remembered Dad telling me that a stream ran through the forest and eventually into town. I figured I’d head that way, find the stream, and maybe idle away some time there with Bandit, leisurely making my way to civilization.

The highway led north, while the woods and stream were somewhat westerly. I walked with the sun at my back, the heat coming down like fiery arrows. My hair dried pretty quick, but by the time I reached the edge of the forest I was wet again, this time with a sheen of sweat. Bandit’s tongue lolled out like a strip of unrolled carpet, yet he wasn’t panting, still moving silently at my side like that Indian ghost dog.

The path to the woods led up a steady incline. When there was still about a quarter mile left to go, I paused with Bandit to rest. From my new vantage point, I looked over the woodlands like a god upon his domain.

To the north I could see the town of Payne, rustic earthy adobe and brick buildings splayed out like an Old West settlement. I could see the roads crisscrossing the municipality from one end to the other, the entirety of the place laid out there below me like a toy model. I half expected to see buggies and wagons and men on horses kicking up dirt clouds, and maybe a blacksmith pounding red-hot metal with a huge hammer. Perhaps a gallows where outlaws and criminals were hanged, looped rope and maybe a corpse swaying in the summer breeze.

I turned back to the woods and, off in the trees a distance, I saw something catch the golden sun like a mirror, twinkling and casting back the light. A hand cupped over my eyes like a visor, I squinted, had to turn away as the sunlight flashed off the object again. I tried to pinpoint its location by some sort of landmark, maybe a tree larger than all the others, or a rock formation that broke the thick landscape around it. There were a couple craggy hills poking about through the surrounding tree coverage, but nothing remarkable.

Nothing I could check on the map in my mind as noteworthy, like a marker on a treasure map.

All the trees looked the same, and though I saw some outcroppings interspersed out among the green landscape, none were very close to that sparkling object. So, I set imaginary crosshairs in the direction of the reflecting light and walked straight as an arrow, hoping for a minimum of obstacles on my route that would make me stray.

“Come on, Bandit,” I said, and he trotted at my heels, big dog smile splitting his face as if this was all that he needed: his boy, a sunny day, and a long walk with no particular destination.

At best I judged the source of the bright light to be a couple hundred yards into the woods, and I came to the stream long before I’d trundled that far among the trees and bushes and fallen limbs. The stream was about two car lengths in width, clear water sparkling the sun in a million daggers of light, and at its center I could only just see the bottom. Vague and distorted water-rippled rocks peppered the riverbed. Fish like silvery lasers darted beneath the surface. The sound of the stream moving and rushing along its course was soft music, and a fine spray—wet and cool—carried the current’s song in the air.

Bandit had seen the fish as well, or smelled them, and he slipped into the water as silently as he walked, a phantasm entering the flow of the Styx. I settled down on a rock that seemed to be formed just for that purpose. I took off my shoes and socks, thinking I’d dip into the water also, its sharp clarity and cleanness inviting me.

Wiping sweat from my forehead, I wished I’d brought a bottle of water. I thought about leaning over to drink from the stream, but seemed to remember hearing something about fish shit in stream and river water, and it making people sick and giving them the shits. Spending the first week of summer squirting diarrhea until my ass was raw didn’t seem such a hot idea. So I didn’t drink the water, tried swallowing some spit in my parched throat instead.

Reckoning I’d have to settle for just dipping my feet in, maybe splashing about with Bandit a little to cool off, I started to do so. A shout and a loud splash from further downstream brought me to a stop with one foot in the water, the other still on the bank. Leaning in the direction of the sound, head cocked to hear better, I watched the flow of the water to where it ran around a bend in the streambed and out of sight.

Bandit’s ears pricked up at the sound also, and he started that way, forgetting the darting fish for the moment. Keeping my voice low, I called for him to wait. We moved along in the water together, boy and dog, one trying to be as stealthy as a ninja, the other naturally so.

A second cry traveled through the air around the bend and, in it this time, I distinctly heard the words “Please! Stop!” and more splashing. Despite the high-pitched whine of the voice, and a decidedly embarrassing nasally sound on the verge of being full-blown crying, I could tell it was a boy’s voice. A kid probably around my age by the sound of it.

Following the whining-almost-crying and the splashing, I heard laughter, at least two or three distinct voices, and I had a good idea of what was going on. As did Bandit, by the way his ears pressed back against his head and he lowered himself until his chest was touching the water. Ready to lunge, lips peeled back in a grimace, even I found him frightening and had to remind myself this was my dog and it wasn’t me that had to be worried.

Around the bend a twisted tree stretched out a gnarly limb as if in greeting. The stream widened here, almost becoming a proper river. The shoreline was rocky and strewn with pebbles and sticks. Three boys, taller and bigger than me, maybe sixteen or seventeen, high school kids definitely, stood among the pebbles and sticks, bending to pick some up from time to time and chucking them into the water. Their target was a fat kid in the water, stripped to his underwear, trying to fend off the incoming missiles with his forearms.

A rock hit him on the breast, a tit larger than most girls’, and he staggered. A stick sailed through the air and struck him on the shoulder. Another rock struck him squarely in his massive belly, making the flesh there ripple like a shockwave. This last impact made him stagger again, then topple, and he fell in what seemed like slow motion, hitting the water and sending a splash and wake like a tanker sinking offshore of the Pacific.

“What’s wrong, Bobby Templeton!” one of the older kids called out, a guy with greased-back hair that made me instantly think of Sarah’s boyfriend back in California. The guy wore tight jeans and a white T-shirt that showed his fairly muscled arms. The guy obviously thought he was some sort of biker or something, maybe thinking greased hair and a muscle shirt balanced out the explosion of acne that pocked his face. “Have a nice trip?”

The other two guys hooted and hollered at this, as if they’d never heard anything funnier. High fives were exchanged all around. The fat boy tried getting up, his legs and arms like dough, and he slipped again and sent up another large splash. I thought to myself that this might be kind of funny if it wasn’t so fucking sad.

“Bobby Templeton!” one of the other guys called out, slimmer than the first, wearing jeans and a suede jacket. He was also shaking with laughter, but more in control of himself as he did so, hands casually at hip pockets. He watched the whole thing with a crooked smirk that made me think of serial killers in movies. “Maybe we ought to call you Chubby Twinkie-by-the-ton!”

The third guy, ironically, not so thin himself but not nearly as fat as the kid in the stream (Bobby Templeton, I told myself), laughed and threw another rock. This one struck the fat boy on the forehead, and I watched him sort of totter there for a moment or two, a hand going to his forehead, finding blood, and then he toppled over into the water again.

As not numbering among the largest kids ever birthed, I’d been in my fair share of fistfights in school and, like then at the stream in the woods, out of school. I wish I could say I gave more than I got, but I don’t honestly know if I’d kept a win and loss scorecard of all my scraps as a kid which side would have the most marks. But Dad had taught me how to throw a punch, much to Mom’s chagrin, and also a few sneaky maneuvers with my legs that used my center of gravity and my opponent’s momentum against them and in my favor. I’d taken punches before, hard ones, and though I didn’t much like them I wasn’t scared of getting hit either.

I looked at the older, bigger kids, and knew my chances with all three of them weren’t that great: as in no chance in hell. I’d fought bigger guys before, and older guys, so I wasn’t really scared about that. It was just a practical matter. I knew I wasn’t some superhero, and held no delusions that if I took them all on I wouldn’t be leaving there with bruises or worse.

But I had Bandit, and figured that evened things out pretty squarely.

Apparently so did he, because he let out a growl so low and deep and vicious that for a moment I was again afraid of being so near him. He sounded like a wolf then, something primal and ferocious, something wild, and I thought that maybe there wasn’t any German shepherd in him at all.

The three high school kids hadn’t seen me yet. They’d squatted to choose again among the smorgasbord of missiles about their feet. Targeting the fat kid in the water once more, taking aim.

Then they heard the growl, and froze. Even the guy in the suede jacket with the Charles Manson face. It was as if a monster had just passed by, a thing from nightmares and dark places, and the primitive man in them all took note.

The three of them turned in my direction, saw me, saw my dog. Their gazes seemed more directed at Bandit than me, but eventually the Manson kid turned his eyes my way.

“Hey, kid,” he said, nodding in my direction like we were acquaintances. He tried to keep that not-so-concerned smirk on his face, like nothing really bothered him. Like he was somehow separate from the rest of the world. But I noted the bead of sweat on his forehead, watched it start to roll down his face. “Call off your dog.”

I’d known his kind before. However this ended up, he wouldn’t let it be. I’d interrupted his fun, his amusement, and he didn’t like it. It was all there in his smirk and eyes. He’d remember me. He’d marked me.

This pretty much meant I had nothing to lose.

“I have an idea,” I said, my voice far sturdier than I felt inside. “How about I take a shit and you eat it?”

What remained of the smiles and good humor of the greasy guy with the head like a planet populated by pimples and the chubby guy was gone in an instant. The lean Manson guy tried to hang on to his smirk, but even that twitched and missed a beat.

“That’s pretty brave for a kid with a big ass dog with him,” said Mr. Smirk. His thumbs were still in his hip pockets as he tried to remain cool and distant from it all.

“That would almost be funny if it wasn’t so fucking retarded,” I said. “Talking about being brave, and you there, three against one, and him smaller than you.”

I hooked a thumb in the fat kid’s direction.

He’d sat up in the stream, blood still trickling from his forehead, watching the whole thing unfolding with an expression short of amazement on his face. He was looking at me and Bandit, and then looking at the three older guys on the shore, back and forth, like he was watching some alien spectacle. I had the urge to check to see if I had tentacles coming out my backside or something.

“He’s hardly smaller than us,” the chubby guy said, and I almost laughed. It was as if in his tight jeans and black shirt he didn’t realize he wasn’t exactly Mr. Universe either. Or maybe he did, I thought with something akin to revelation, and that’s why he said it.

“The lard-ass pot calling the kettle black,” I said, and the fat boy (Bobby) barked a quick laugh before stifling it with a hand to his mouth. The three high school guys gave him a brief hateful look before turning back to me.

“Look,” Mr. Smirk said. One hand finally unhooked from his jeans pocket and went palm up in front of him, in a friendly where-is-this-getting-us gesture. “I don’t think you realize what you’re getting yourself into. Just take your dog and walk away and I’ll forget I ever saw you here.”

He’d forget me as soon as he forgot how to breathe, and that wasn’t anything I was going to hold my breath for. So I decided to roll with it and keep on going.

“Look,” I said, giving him the same friendly, conversational palm-up gesture. “I don’t think you realize you’re a dickweed.”

“You fucking asshole,” Mr. Pudge said, and took a step forward. Perhaps emboldened by his friend’s initiative, Mr. Planet Pimple Head stepped forward too.

Bandit’s growl, having continued to rumble through this exchange, rose a notch, from bestial to demonic. Mr. Smirk stopped his friends with either arm outstretched to block them.

“Look,” Mr. Smirk started again, “let’s make a deal. This is a small town. You’re obviously new here. You’re not going to have your dog with you every minute of every day. You leave now, instead of killing you, I just kick your ass one time, someday, and then we call it even.”

“Look,” I said, mocking his nonchalant tone, “I have a deal for you. A counteroffer, if you dumbshits know what that means. My dog rips one of your guys’ nutsacks off, and I find the largest rock I can and beat the living shit out of one of you other two. That’s two-thirds chance of any of the three of you getting messed up real bad. Either nutsack chewed off,” I held one hand up, “or head bashed in,” and then the other. Lifting them up and down, my hands weighed something invisible like they were scales.

“Personally,” Bobby said, and we all turned to him, equally surprised that he’d found the guts to talk, “I’d like to keep my nuts.”