Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Complete Rob Bell: His Seven Bestselling Books, All in One Place»

THE COMPLETE ROB BELL

Velvet Elvis

Sex God

Jesus Wants to Save Christians

Drops Like Stars

Love Wins

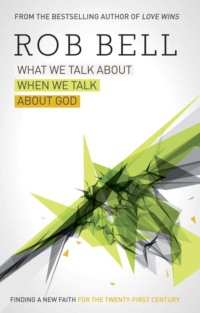

What We Talk About When We Talk About God

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

VELVET ELVIS

Repainting the Christian Faith

ROB BELL

Velvet Elvis

Cover

Title Page

Preface - Welcome to My Velvet Elvis

Movement One - Jump

Movement Two - Yoke

Movement Three - True

Movement Four - Tassels

Movement Five - Dust

Movement Six - New

Movement Seven - Good

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Endnotes

PREFACE Welcome to my Velvet Elvis

In my basement, behind some bikes and suitcases and boxes, sits a Velvet Elvis. A genuine, bought-by-the-side-of-the-road Velvet Elvis. And to say that this painting captures The King in all his glory would be an understatement. It’s not the young Elvis—the thin one with the slicked-back hair in those black-and-white concert photos in which he’s playing a guitar that’s not plugged in. And it’s not the old Elvis—the big one in the shiny cape singing to old women in Hawaii. My painting is the “Pre-doughnut Elvis.”

A touch of blue in the hair; the tall, white collar that suggests one of those polyester jumpsuits; and those lips . . . if you stare long enough, you might even see them quiver.

But I think the best part of my Velvet Elvis is the lower left-hand corner, where the artist simply wrote a capital R and then a period.

R.

Because when you’re this good, you don’t even have to write your whole name.

What if, when the artist was done with this masterpiece, R. had announced there was no more need for anyone to paint, because he or she had just painted the ultimate painting? What if R. had held a press conference, unveiled his painting, and then called on all painters everywhere to put down their brushes, insisting that since the ultimate painting had been painted, there was simply no need for any of them to continue their work?

We would say that R. had lost his mind. We say this because we instinctively understand that art has to, in some way, keep going. Keep exploring, keep arranging, keep shaping and forming and bringing in new perspectives.

For thousands of years followers of Jesus, like artists, have understood that we have to keep going, exploring what it means to live in harmony with God and each other. The Christian faith tradition is filled with change and growth and transformation. Jesus took part in this process by calling people to rethink faith and the Bible and hope and love and everything else, and by inviting them into the endless process of working out how to live as God created us to live.

The challenge for Christians then is to live with great passion and conviction, remaining open and flexible, aware that this life is not the last painting.

Times change. God doesn’t, but times do. We learn and grow, and the world around us shifts, and the Christian faith is alive only when it is listening, morphing, innovating, letting go of whatever has gotten in the way of Jesus and embracing whatever will help us be more and more the people God wants us to be.

There are endless examples of this ongoing process, so I’ll describe just one. Around 500 years ago, a man named Martin Luther raised a whole series of questions about the painting the church was presenting to the world. He insisted that God’s grace could not be purchased with money or good deeds. He wanted everyone to have their own copy of the Bible in a language they could read. He argued that everyone had a divine calling on their lives to serve God, not just priests who had jobs in churches. This concept was revolutionary for the world at that time. He was articulating earth-shattering ideas for his listeners. And they heard him. And something big, something historic, happened. Things changed. Thousands of people connected with God in ways they hadn’t before.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Luther was taking his place in a long line of people who never stopped rethinking and repainting the faith. Shedding unnecessary layers and at the same time rediscovering essentials that had been lost. Luther’s work was part of what came to be called the Reformation. Because of this movement, the churches he was speaking against went through their own process of rethinking and repainting, making significant changes as a result.

And this process hasn’t stopped.

It can’t.

In fact, Luther’s contemporaries used a very specific word for this endless, absolutely necessary process of change and growth. They didn’t use the word reformed; they used the word reforming. This distinction is crucial. They knew that they and others hadn’t gotten it perfect forever. They knew that the things they said and did and wrote and decided would need to be revisited. Rethought. Reworked.

I’m part of this tradition.

I’m part of this global, historic stream of people who believe that God has not left us alone but has been involved in human history from the beginning. People who believe that in Jesus, God came among us in a unique and powerful way, showing us a new kind of life. Giving each of us a new vision for our life together, for the world we live in.

And as a part of this tradition, I embrace the need to keep painting, to keep reforming.

By this I do not mean cosmetic, superficial changes like better lights and music, sharper graphics, and new methods with easy-to-follow steps. I mean theology: the beliefs about God, Jesus, the Bible, salvation, the future. We must keep reforming the way the Christian faith is defined, lived, and explained.

Jesus is more compelling than ever. More inviting, more true, more mysterious than ever. The problem isn’t Jesus; the problem is what comes with Jesus.

For many people the word Christian conjures up all sorts of images that have nothing to do with who Jesus is and how he taught us to live. This must change.

For others, the painting works for their parents, or it provided meaning when they were growing up, but it is no longer relevant. It doesn’t fit. It’s outdated. It doesn’t have anything to say to the world they live in every day. It’s not that there isn’t any truth in it or that all the people before them were misguided or missed the point. It’s just that every generation has to ask the difficult questions of what it means to be a Christian here and now, in this place, at this time.

And if this difficult work isn’t done, where does the painting end up?

In the basement.

Here’s what often happens: Somebody comes along who has a fresh perspective on the Christian faith. People are inspired. A movement starts. Faith that was stale and dying is now alive. But then the pioneer of the movement—the painter—dies and the followers stop exploring. They mistakenly assume that their leader’s words were the last ones on the subject, and they freeze their leader’s words. They forget that as that innovator was doing his or her part to move things along, that person was merely taking part in the discussion that will go on forever. And so in their commitment to what so-and-so said and did, they end up freezing the faith.

What gets lost is the truth that whoever painted that version was just like us, searching for God and experiencing God and trying to get a handle on what the Christian faith looks like. And then a new generation comes along living in a new day and a new world, and they have to keep the tradition going or the previous paintings are going to end up in the basement.

The tradition then is painting, not making copies of the same painting over and over. The challenge of the art is to take what was great about the previous paintings and incorporate that into new paintings.

And in the process, make something beautiful—for today.

For many Christians, the current paintings are enough. The churches, the books, the language, the methods, the beliefs—there is nothing wrong with it. It works for them and meets their needs, and they gladly invite others to join them in it. I thank God for that. I celebrate those who have had their lives transformed in these settings.

But this book is for those who need a fresh take on Jesus and what it means to live the kind of life he teaches us to live. I’m part of a community, a movement of people who have been living, exploring, discussing, sharing, and experiencing new understandings of Christian faith.

And we love it. We are alive in ways we never thought possible. We are caught up in something we gladly give our lives to. This is the place that I write from: a place of joy and freedom, as a member of a community wanting to invite others to come along on the journey. We are just getting started. I have as many questions as answers, and I’m convinced that we’re only scratching the surface. What I do know is that this pursuit of Jesus is leading us backward as much as forward.

If it is true, then it isn’t new.

I am learning that what seems brand new is often the discovery of something that’s been there all along—it just got lost somewhere and it needs to be picked up, dusted off, and reclaimed. I am learning that I come from a tradition that has wrestled with the deepest questions of human existence for thousands of years. I am learning that my tradition includes the rabbis and reformers and revolutionaries and monks and nuns and pastors and writers and philosophers and artists and every person everywhere who has asked big questions of a big God.

Welcome to my Velvet Elvis.

MOVEMENT ONE Jump

Several years ago my parents and in-laws gave our boys a trampoline. A fifteen-footer with netting around the outside so kids don’t end up headfirst in the flowers. Since then my boys and I have logged more hours on that trampoline than I could begin to count. When we first got it, my older son, who was five at the time, discovered that if he timed his bounce with mine, he could launch higher than if he was jumping on his own.

I remember the first time he called my wife, Kristen, out into the backyard to watch him jump off of my bounce. Now mind you, up until this point he was maybe getting a foot higher because of his new technique. But this one particular time, when my wife was watching for the first time, something freakish happened in the space-time continuum. When he jumped, there was this perfect convergence of his weight and my weight and his jump and my jump, and I’m sure barometric pressure and air temperature had something to do with it too, because he went really high.

I don’t mean a few feet off the mat. I mean he went over my head. Forty pounds of boy, clawing the air like a cat thrown from a second-story window, and a man making eye contact with his wife and thinking, This is not good.

She told us she didn’t think our new trick was very safe and we should be careful. Which we were.

Until she went inside the house.

It is on this trampoline that God has started to make more sense to me. Because when it comes to faith, everybody has it. People often tell me they could never have faith, that it is just too hard. The idea that some people have faith and others don’t is a popular one. But it is not a true one. Everybody has faith. Everybody is following somebody. What often happens is that people with specific beliefs about God end up backed into a corner, defending their faith against the calm, cool rationality of others. As if they have faith and beliefs and others don’t.

But that is not true. Let’s take an example: Some people believe we were made by a creator who has plans and purposes for his creation, while others believe there is no greater meaning to life, no grand design, and we exist not because of some divine intention but because of random chance. This is not a discussion between people of faith and people who don’t have faith. Both perspectives are faith perspectives, built on systems of belief. The person who says we are here by chance and there is no greater meaning has just as many beliefs as the person who says there’s a creator. Maybe even more.

Think about some of the words that are used in these kinds of discussions, one of the most common being the phrase “open-minded.” Often the person with spiritual convictions is seen as close-minded and others are seen as open-minded. What is fascinating to me is that at the center of the Christian faith is the assumption that this life isn’t all there is. That there is more to life than the material. That existence is not limited to what we can see, touch, measure, taste, hear, and observe. One of the central assertions of the Christian worldview is that there is “more.”1 Those who oppose this insist that this is all there is, that only what we can measure and observe and see with our eyes is real. There is nothing else. Which perspective is more “closed-minded”? Which perspective is more “open”?

An atheist is a person of tremendous faith. In our discussions about the things that matter most then, we aren’t talking about faith or no faith. Belief or no belief. We are talking about faith in what? Belief in what? The real question isn’t whether we have it or not, but what we have put it in.

Everybody follows somebody. All of us make decisions every day about what is important, how to treat people, and what to do with our lives. These decisions come from what we believe about every aspect of our existence. And we got our beliefs from somewhere. We have been formed, every one of us, by this complicated mix of people and places and things. Parents and teachers and artists and scientists and mentors—we are each taking all of these influences and living our lives according to which teachings we have made our own. Some insist that they aren’t influenced by any person or any religion, that they think for themselves. And that’s an honorable perspective. The problem is they got that perspective from . . . somebody. They’re following somebody even if they insist it is themselves they are following.

Everybody is following somebody. Everybody has faith in something and somebody.

We are all believers.

Way

As a Christian, I am simply trying to orient myself around living a particular kind of way, the kind of way that Jesus taught is possible. And I think that the way of Jesus is the best possible way to live.

This isn’t irrational or primitive or blind faith. It is merely being honest that we all are living a “way.”

I’m convinced being generous is a better way to live.

I’m convinced forgiving people and not carrying around bitterness is a better way to live.

I’m convinced having compassion is a better way to live.

I’m convinced pursuing peace in every situation is a better way to live.

I’m convinced listening to the wisdom of others is a better way to live.

I’m convinced being honest with people is a better way to live.

This way of thinking isn’t weird or strange; it is simply acknowledging that everybody follows somebody, and I’m trying to follow Jesus.

Over time when you purposefully try to live the way of Jesus, you start noticing something deeper going on. You begin realizing the reason this is the best way to live is that it is rooted in profound truths about how the world is. You find yourself living more and more in tune with ultimate reality. You are more and more in sync with how the universe is at its deepest levels.

Jesus’s intention was, and is, to call people to live in tune with reality. He said at one point that if you had seen him, you had “seen the Father.”2 He claimed to be showing us what God is like. In his compassion, peace, truth telling, and generosity, he was showing us God.

And God is the ultimate reality. There is nothing more beyond God.

Jesus at one point claimed to be “the way, the truth, and the life.” Jesus was not making claims about one religion being better than all other religions. That completely misses the point, the depth, and the truth. Rather, he was telling those who were following him that his way is the way to the depth of reality. This kind of life Jesus was living, perfectly and completely in connection and cooperation with God, is the best possible way for a person to live. It is how things are.

Jesus exposes us to reality at its rawest.

So the way of Jesus is not about religion; it’s about reality.

It’s about lining yourself up with how things are.3

Perhaps a better question than who’s right, is who’s living rightly?

Springs

This is where the springs on the trampoline come in. When we jump, we begin to see the need for springs. The springs help make sense of these deeper realities that drive how we live every day. The springs aren’t God. The springs aren’t Jesus. The springs are statements and beliefs about our faith that help give words to the depth that we are experiencing in our jumping. I would call these the doctrines of the Christian faith.

They aren’t the point.

They help us understand the point, but they are a means and not an end. We take them seriously, and at the same time we keep them in proper perspective.

Take, for example, the doctrine—the spring—called the Trinity. This doctrine is central to historic, orthodox Christian faith. While there is only one God, God is somehow present everywhere. People began to call this presence, this power of God, his “Spirit.” So there is God, and then there is God’s Spirit. And then Jesus comes among us and has this oneness with God that has people saying things like God has visited us in the flesh.4 So God is one, but God has also revealed himself to us as Spirit and then as Jesus. One and yet three. This three-in-oneness understanding of God emerged in the several hundred years after Jesus’s resurrection. People began to call this concept the Trinity. The word trinity is not found anywhere in the Bible. Jesus didn’t use the word, and the writers of the rest of the Bible didn’t use the word. But over time this belief, this understanding, this doctrine, has become central to how followers of Jesus have understood who God is. It is a spring, and people jumped for thousands of years without it.5 It was added later. We can take it out and examine it. Discuss it, probe it, question it. It flexes, and it stretches.

In fact, its stretch and flex are what make it so effective. It is firmly attached to the frame and the mat, yet it has room to move. And it has brought a fuller, deeper, richer understanding to the mysterious being who is God.

Once again, the springs aren’t God. They have emerged over time as people have discussed and studied and experienced and reflected on their growing understanding of who God is. Our words aren’t absolutes. Only God is absolute, and God has no intention of sharing this absoluteness with anything, especially words people have come up with to talk about him. This is something people have struggled with since the beginning: how to talk about God when God is bigger than our words, our brains, our worldviews, and our imaginations.

In the book of Deuteronomy, Moses reminds the people that when they encountered God, they “heard the sound of words but saw no form.”6

No form, no shape.

Nothing you could see.

In Moses’s day, the way you honored and respected whatever gods you followed was by making carvings or sculptures of them and then bowing down to what you had made. These were gods you could get your mind around. Moses is confronting people with an entirely new concept of what the true God is like. He is claiming that no statue or carving could ever capture this God, because this God has no shape or form.

This was a revolutionary idea in the history of religion.

You are holding a book in your hands. It has shape and volume and weight and all the stuff that makes it a thing.

It has thingness.

This book has edges and boundaries that define it as a finite thing. It is a book and nothing else.

But the writers of the Bible go to great lengths to describe God as a being with no edges or boundaries or limits. God has no thingness because there’s no end to God.

Or as the question goes in the book of Job: “Can you probe the limits of the Almighty?”7

It makes sense, then, in a strange sort of way, that when Moses asks God for his name, God replies, “I am.”8

Doesn’t really clear things up, does it?

Moses is looking for a being he can wrap his mind around. Is this the god of water or power or soil or fertility? All the other gods made sense; you could understand them—who they were and what they did and what they stood for. But this God is different. Mysterious. Unfathomable.

“I am.”

The name’s origins come from the verb to be, so some read it as “I will be who I will be.”

Others suggest it should be read like this: “I always have been, I am, and I always will be.”

Perhaps this is God’s way of saying, “If your goal is to figure me out and totally understand me, it’s not going to happen. Even my name is more than you can comprehend.”

Later Moses says to God, “Now show me your glory.”

Which is our way of saying, “I need more. I need something I can see. Something tangible.”

God’s response? He tells Moses to go stand on a rock, because he’s going to pass by. He explains to Moses that no one can see him and live, so he’ll cover Moses with his hand (God’s hand?) as he passes by, and then he says, “I will remove my hand and you will see my back.”9

The ancient rabbis had all sorts of things to say about this passage, but one of the most fascinating things they picked up on is the part about God’s back. They argued that in the original Hebrew language, the word back should be understood as a euphemism for “where I just was.”

It is as if God is saying, “The best you’re going to do, the most you are capable of, is seeing where I . . . just . . . was.”

That’s the closest you are going to get.

If there is a divine being who made everything, including us, what would our experiences with this being look like? The moment God is figured out with nice neat lines and definitions, we are no longer dealing with God. We are dealing with somebody we made up. And if we made him up, then we are in control. And so in passage after passage, we find God reminding people that he is beyond and bigger and more.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.