Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The 1,000-year-old Boy»

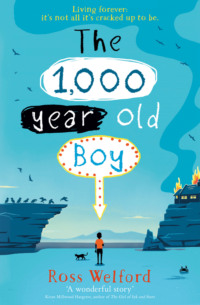

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2018

Published in this ebook edition in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Text copyright © Ross Welford 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover illustration © Tom Clohosy Cole

Ross Welford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008256944

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008256951

Version: 2017-12-13

Praise for The 1,000-year-old Boy:

‘Boasts all the ingredients of a great book: brave kids, bold storytelling and a blistering plot. Full of humour and heart’ Abi Elphinstone, author of The Dreamsnatcher

‘The 1000-year-old Boy is a breathtakingly epic story that you won’t be able to put down. In Alfie, Ross Welford has created an unusual and fascinating boy who you are rooting for right from the first word. An original, surprising, moving and compelling read – I loved it’ M. G. Leonard, author of Beetle Boy

‘A wonderful story told with Welford’s trademark warmth, wit and cleverness. Another great read from one of my favourite middle-grade writers’ Kiran Millwood Hargrave, author of The Girl of Ink and Stars

‘A cracking story about family and friendship that spans all ages’ Christopher Edge, author of The Many Worlds of Albie Bright

‘Delightful, charming and filled with humour. This is a unique and uplifting tale of a boy who lives a thousand years, yet still remains young at heart’ Peter Bunzl, author of the Cogheart Adventures

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for The 1,000-year-old-Boy

Part One

Alfie

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Aidan

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Part Two

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Part Three

Chapter Fifty-six

Chapter Fifty-seven

Chapter Fifty-eight

Chapter Fifty-nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-one

Chapter Sixty-two

Chapter Sixty-three

Chapter Sixty-four

Chapter Sixty-five

Chapter Sixty-six

Chapter Sixty-seven

Chapter Sixty-eight

Chapter Sixty-nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-one

Chapter Seventy-two

Chapter Seventy-three

Chapter Seventy-four

Chapter Seventy-five

Chapter Seventy-six

Chapter Seventy-seven

Chapter Seventy-eight

Chapter Seventy-nine

Chapter Eighty

Part Four

Chapter Eighty-one

Chapter Eighty-two

Chapter Eighty-three

Chapter Eighty-four

Chapter Eighty-five

Chapter Eighty-six

Chapter Eighty-seven

Chapter Eighty-eight

Chapter Eighty-nine

Chapter Ninety

Chapter Ninety-one

Chapter Ninety-two

Chapter Ninety-three

Chapter Ninety-four

Chapter Ninety-five

Chapter Ninety-six

Chapter Ninety-seven

Chapter Ninety-eight

Chapter Ninety-nine

Chapter One Hundred

Chapter One Hundred and One

Chapter One Hundred and Two

Chapter One Hundred and Three

Chapter One Hundred and Four

Chapter One Hundred and Five

Author’s Note

Keep Reading …

Books by Ross Welford

About the Publisher

Would you like to live forever? I am afraid I cannot recommend it. I am used to it now, and I do understand how special it is. Only I want to stop now. I want to grow up like you.

This is my story. My name is Alve Einarsson. I am a thousand years old. More, actually.

Are we friends? In that case, just call me Alfie. Alfie Monk.

South Shields, AD 1014

We sat on the low cliff, Mam and I, overlooking the river mouth, and watched the smoke from our village over on the other side pluming into the sky and mixing with the clouds.

Everyone calls the river the Tyne. Back then, we pronounced it ‘Teen’, but it was just our word for river.

As we sat, and Mam wept and cursed with fury, we heard screams from across the water. The smell of smoke from the burning wooden fort on the clifftop drifted towards us. People – our neighbours mostly – huddled on the opposite bank, but Dag the ferryman was not going to go back for them. Not now: he would be killed too. He had run away from us, stammering apologies, as soon as his raft had touched the shore.

Above the people cowering on the bank, the men who had come in boats appeared. They paused – arrogantly, fearlessly – then walked over to their prey, swords and axes at the ready. I saw some people entering the water to try to escape. They would not get far: a smaller boat waited mid-river to intercept them.

I lowered my head and buried it in Mam’s shawl, but she pulled it away and wiped her eyes. Her voice trembled with rage.

‘Sey, Alve. Sey!’ That is how we spoke then. ‘Old Norse’ it is called now, or a dialect of it. We didn’t call it anything. She meant, ‘Look! Look at what they are doing to us, those men who have come from the north in their boats.’

But I could not. Getting up, I walked in a kind of daze for some distance, but I could still hear the murder, still smell the smoke. I felt wretched for being alive. Behind me, Mam pulled the little wooden cart that was loaded with whatever stuff we’d managed to fit onto Dag’s, river ferry.

My cat Biffa walked beside us, darting into the grass on the side of the path in pursuit of a mouse or a grasshopper. Normally this made me smile, but I felt as empty as if I had been cut open.

A mile or two on, Mam and I found a cave in a deep, sheltered bay. The sun was strong enough to use the old fire-glass that had belonged to Da: a curved, polished crystal that focused the sunlight into a thin beam that would start a fire. I was scared the raiders would come after us, but Mam said they would not, and she was right. We had escaped.

Three days later, we saw their boats heading out to sea again and I made the biggest mistake of my life. A mistake that I waited a thousand years to put right.

If you want to ask me, ‘Why did you do it?’, go ahead: I do not mind. I have asked myself that many, many times. I still do not know the whole answer.

All I can say is that I was young, and very, very scared. I wanted to do something – anything – that would make me feel stronger, better able to help Mam, better able to protect us both.

And so I became a Neverdead, like Mam.

It began long ago, and when I say long ago I mean ages, literally. This is what happened.

My father had owned five of the small glass balls that were called livperler.

Life-pearls.

They were the most valuable things we possessed. Mam said that they might be the most valuable things in the world, ever.

People had killed to obtain them; Da had died trying to keep them. And so we told no one that we had them.

Now there were three left. One for Mam, and two for me when I was older.

I knew all that. Mam had told me enough times. ‘Not until you are grown, Alve. You must be patient.’

But I could not wait.

On the third evening in the cave, while Mam was out looking for fresh water, I opened the little clay pot and took out the livperler. Although they were old, the glass marbles shone in the half-twilight from outside, the thick liquid within seeming to glow amber when I held one near the fire.

Biffa sat up on a little rocky shelf on the opposite side of the fire, her yellow eyes shining like the glass balls. Did she know? She mewled: the little cat-growl that made us think she was talking to us. Biffa often seemed to know things.

Crouching on my hunkers, I took the knife, the little steel one that had belonged to Da, with the blade that hinged into the wooden handle, and held it to the flame. I glanced at the mouth of the cave to check I was alone, and swallowed hard.

When I drew the hot blade twice across my upper arm, the blood seeped out. Two short slashes, like the scars Mam had. Like Da had had. I do not know if doing it twice made any difference; probably not. It was just the way.

It did not hurt until I used my thumbs to pull the wounds apart. I bit down on the life-pearl and the glass cracked. The yellowish syrup oozed out like the blood from my cuts. I gathered it on my fingertips and rubbed it into the wounds. Then I did it again, and again, until there was none left. It stung, like a fresh nettle in the spring.

What happened next was an accident. I have played it over and over in my mind, like people play ‘videotapes’ today. Could I have done anything differently?

I do not know.

I think Biffa was just curious. She cannot have known – but, as I said, she was a very knowing cat. Suddenly she gave another little growl and leapt at me, right across the low flames of the fire. The knife was still in my hand and, without thinking, I raised it: a defensive reflex. It nicked her front paw slightly, but she did not mewl again. When she landed, I spun round and, in that action, my tunic dislodged another life-pearl from the low rock shelf where I had placed them. I was unbalanced, and my bare foot came down on it, hard, and it cracked open.

I stared at it, horrified, for a few seconds.

It was bad enough that I had disobeyed Mam’s orders. But I had now wasted another precious life-pearl.

The thick amber liquid began to drip out of the rock. Thinking only that it should not be wasted, I grasped Biffa by the long skin of her neck and rubbed the liquid into her cut paw.

(It was not mischief, as I said to Mam again and again over the years. I was just trying not to waste it.)

Then I wrapped up my arm with a long strip of clean cloth, and tied another round Biffa’s leg. She did not even seem to mind. She licked her whiskers, yawned and curled up again. I could see Mam’s shape against the blue twilight sky as she came back to the cave with a bucket of water, and I was overwhelmed with shame.

I sometimes think I still am.

By then, I had seen eleven winters.

I was to stay eleven years old for more than a thousand years.

All of that happened ages ago.

I have tried telling my story before, but I soon learnt that people do not want to know. I have to leave out crucial details like the life-pearls, and so people think I am teasing them (at best) or that I am dangerously mad (at worst).

So I stay schtum, as you say.

I sometimes wonder if people’s reactions would be different if I looked old? That is, if I were wrinkled and stooped and bald, with a quavery voice, and huge, veiny ears and badly fitting clothes. Then again, people would not bother with the ‘teasing’ bit, would they? They would immediately assume that age had sent me mad.

‘Bless ’im, old Alf,’ they would say. ‘He was on about the Vikings again today.’

‘Was ’e? Aww. It was Charles Dickens yesterday. Reckoned he’d met him!’

‘Really? Poor old soul. Mind, he’s harmless, in’t he? Away with the mixer, like, but harmless.’

As it is, I do not look old at all: I look about eleven.

At the point I stopped ageing, the Vikings had more or less completed their occupation of north-eastern England. It was the Scots that Mam and I were fleeing. It was to be another fifty or more years before the south of the country was invaded: 1066, by the Normans (who were basically Vikings who had learnt French, if you ask me, but nobody does. Nor-man, north-man – you can see the link).

And, in case you are interested, I did meet Charles Dickens, but not until many, many years later.

See? You do not believe me, do you? I cannot really blame you, seeing as I am the last remaining Neverdead on earth. And, now that Mam has gone, living forever is no life at all.

The trouble is, if you do not believe me, what chance do I have of convincing Aidan Linklater and Roxy Minto? I will need their help if I am to lift the curse of my endless life.

And if they do not believe me then I am, as you say these days, stuffed.

I should probably start by telling you why I’m hacked off. Get it out of the way. Then we can get onto how I came to meet Alfie, and my life changed forever.

Whitley Bay, present day

For a start, we’ve moved house. That’s bad enough. But get this:

1. It’s a smaller house. Much smaller, with hardly any back garden – just a scruffy yard that’s way too small to kick a ball in. Mum has reminded me (more than once) that I’m lucky to live in a house with any outside space at all and, when she says that, I feel guilty, and sorry that I even mentioned it because I know why we’ve moved. Thing is, my friend Mo, who lives in a flat, used to come round to our old house because he had no garden, but now there’s no point, is there?

2. If people come to stay, I will now have to share a room with Libby who’s a pain at the best of times. She’s seven and likes My Little Pony.

3. Inigo Delombra, who’s in my year at school, now lives in my old house. I think he even has my old room. He smirks at me every time I see him, as if to say, ‘You sad loser.’

At least I haven’t had to move school, but, with the way things are going with Spatch and Mo, I might as well have.

Another thing: Mum and Dad are arguing all the time. They’ve always argued – ‘bickering’ they call it – but lately it’s become louder, and they think I don’t notice. It’s money – always money. I don’t know the details. All I know is that they made a ‘bad investment’, and Mum says it was Dad’s fault. Mum now works in a call centre and hates it. I found Libby listening at the top of the stairs the other night.

She said, ‘Are they going to get divorced, Aidan?’

I had to say, ‘No, of course not.’ Her chin wobbled but she didn’t cry. Not in front of me, anyway, which is just as well because it would probably have set me off too.

So with that lot out of the way …

Be honest. If some kid that you’d just met told you he was a thousand years old, what would your reaction be?

You’d laugh, maybe, and say, ‘Yeah, right!’

Or you might ignore him – you know: don’t provoke the nutter, and all that.

You could, I suppose, come back with a zinger, like, ‘And I’m the Queen of Sheba.’

OK, so I’m not big on zingers, but you get the idea.

So when Alfie said to me, ‘Aidan, I am more than one thousand years old,’ obviously I didn’t believe him.

And then I had to because, although it was unbelievable, it was the truth.

But, for it to make sense, I’m going to have to rewind a bit.

We moved in – me, Mum, Dad, Libby – at the start of the Easter holidays, and everything was unpacked in three days. My Xbox was smashed in the move. I asked Mum if I could get another one, and she just gave this sad-sounding little laugh, which I suppose means no. She said we had ‘other priorities’ and that made me feel bad for asking.

I had the rest of the holidays stretching out before me.

‘Call up your friends, go down on the beach,’ said Mum every five minutes.

Problem with that was Spatch was away in Naples with his Italian grandparents, where he goes every Easter; worse – he’d invited Mo to go with him. And not me.

I pretended I wasn’t hurt when they told me, but I was. When I talked to Mum about it, she was all like, ‘Oh well – we couldn’t have afforded the air fare, anyway, so no harm done,’ but that’s not the point, is it? Spatch was a bit embarrassed, I think. He said it was because there wasn’t room at his grandparents’ farmhouse, but I’ve seen pictures and it’s huge, and besides I’d have been happy to sleep on the floor. I nearly said that, but I’m glad I didn’t.

To ‘put the tin hat on it’ as Dad says, Aunty Alice and Uncle Jasper came to visit. Aunty Alice is OK, but Jasper? Sheesh.

I know Dad wasn’t happy because I heard him moaning to Mum: ‘Can’t they stay in a hotel, for heaven’s sake? It’s not like we’ve got loads of space.’

‘She’s my sister, Ben.’

Dad just tutted and rolled his eyes.

So, day four of the holidays. Aunty Alice and Jasper had arrived that morning, and I had moved into Libby’s room, on an airbed. She was at Brownie camp for the next couple of days so at least I wasn’t actually sharing with her yet, but still …

We all sat in the kitchen among the boxes left by the removal firm. Dad’s not working at the moment, so he was at home and he made tea and asked about Jasper’s boat (it’s a ‘safe topic’, apparently). Mum fussed over Aunty Alice’s blouse. Aunty Alice is much older than Mum and Jasper is much younger than Aunty Alice, although – thanks to his beard – he looks older than both of them, if that makes sense.

After Aunty Alice had said how much I’d grown, just about the only thing directed at me was Jasper saying:

‘And what about you, son? Are you getting enough of the old fresh stuff? You look like a flamin’ ghost!’ and then he grinned, showing his long white teeth, as if he didn’t really mean it, but I could tell that he did.

Aunty Alice said, ‘Aw, Jasper, he looks lovely!’, and Mum said to him with the faintest edge to her voice:

‘He’s fine, Jasper. Aren’t you, Aidan?’

I nodded vigorously, as if by nodding I could show my uncle that I was – to borrow one of his phrases – ‘as fit as a lopp’.

He went hmphh, and added, ‘Sea air. A bit of the old ventum maris. That’s what you need, son,’ then took a noisy slurp of his tea (black, no sugar).

He talks like that a lot, does Jasper. So far as I can tell, he has no regional accent, and no foreign accent, either. At times, he sounds slightly American, and at others more Australian, when his voice goes up at the end of a sentence as if he’s asking a question? It’s hard to work out. He was born in Romania and has narrow dark eyes – almost black – behind tinted glasses, and he’s lived in lots of countries.

I asked him once where he was from. ‘Just call me a nomad,’ he said, baring his teeth. Between you and me, I’m terrified of him.

With my milk finished and having heard the words ‘prime minister’ come from under Jasper’s beard, I figured it was time to make myself scarce. Once anyone mentions the government, the conversation – so far as I’m involved in it – is not going to improve.

‘I’m going outside,’ I said, and I got a grunt of what might have been approval from Jasper.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.