Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Beechwood Airship Interviews»

COPYRIGHT

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by The Friday Project in 2015

Copyright © Dan Richards 2015

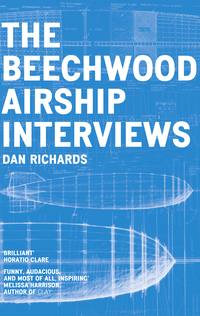

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover by Stanley Donwood

Dan Richards asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008105211

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780008105228

Version: 2015-09-11

For Jo

Many are prepared to suffer for their art. Few are prepared to learn to draw.

– Simon Munnery

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

INTRODUCTION/LIMINAL SPACE

BILL DRUMMOND

RICHARD LAWRENCE

STANLEY DONWOOD

JENNY SAVILLE

DAVID NASH

MANIC STREET PREACHERS

DAME JUDI DENCH

CALLY CALLOMON

SHERYL GARRATT

VAUGHAN OLIVER

JANE BOWN

STEVE GULLICK

STEWART LEE

THE BUTCHER OF COMMON SENSE

ROBERT MACFARLANE

EPILOGUE

Footnotes

The Butcher of Common Sense Footnotes

Thanks

Bibliography

Discography

List of Illustrations

About the Author

Also by Dan Richards

About the Publisher

LIMINAL SPACE

In the summer of 2006 I moved to Norwich from my family home in Bristol to begin a Creative Writing MA at the Art School.

It was a year since I’d graduated from an English Literature and Philosophy BA at the University of East Anglia. I had spent the intervening months working in a bookshop staffed entirely by graduates sheltering from an indifferent world, presided over by a weirdly ageless Brylcreemed man who, when he wasn’t smoking on the roof – arcing his dog-ends languidly into the yard of the adjacent church – would lock himself in his attic office or materialise at your elbow to relate how his father nursed the captive Rudolf Hess.

The shop had a very limited selection of Art books and an even meaner smattering of Photography and Transport.* There was no demand, we were told, and it was this message that we passed on to any customer who enquired, taking great pleasure in directing them up to the ‘better stocked, less expensive shop’ at the top of the road (‘where we would much prefer to work’).

I had no idea what I was doing at the shop but day after day I’d be there, going through the motions of retail. I’d reached an impasse. It was relatively easy work and brought in a small wage, which I’d eke out during the week so I could catch a train to the South Coast to see my girlfriend at weekends. Sometimes I’d get to Brighton and she’d be happy to see me. Sometimes not. Sometimes she’d say, ‘I’m not sure how I feel about you being here … turning up like this …’ and I’d freeze there on the doorstep; tired and punctured, foolish – as if I’d spoilt the most simple of tasks: just turn up and don’t be shit.

Life in Barcelona-on-Sea unravelled as a mess of well-meant gestures and hissed upset. I was sure we had it in us to be happy but we weren’t; we really weren’t.

This went on for months.

I’d think about us all the week while stickering 3 for 2s or directing people up the road, but in my head she smiled more and shouted less.

In retrospect I’d been sleepwalking through many things. She left fairly suddenly. She had indeed been unhappy for a long time. I received a postcard quoting Virginia Woolf’s suicide note as an unequivocal gesture of severance.

That was it.

I moved up to Norwich earlier than planned and drank a lot of gin on my own in a conservatory.

Then I got a cat.

Then I got a night job washing dishes in a pub.

I’d return home in the small hours covered in sink dross, drink more gin and complain to the cat about love.

It became clear that I needed direction, to begin something new, or I’d go mad, fill my sink-drossed smock with bricks and throw myself into a pond.

I threw myself into the art school instead.

• • • • •

In the weeks before term started, I began working in the Student Union bar – a large timber-beamed hall above the canteen – a building which put me in mind of St Pancras Station, all mustard brickwork, corkscrew chimneys and gothic arches; an eccentric building which seemed to embody the idea of an art school.

Accessed up a spiral staircase in a turret tucked away, the bar had a welcoming, secret feel and it was always great to see freshers double-take on first discovery, as I had – caught out by the size of the space, drawn in by the warmth towards the silhouetted people clustered around long tables and stood at the bar while candle shadows flickered the roof joists high above.

Like a massive womb … with Jägermeister.

Hulking cast-iron radiators hugged the walls and creaked, their heat rippling the curtains. The hall was always warm, even on the dark mornings as I swept and served coffee to the few brave souls awake – or yet to go to sleep.

On quiet evenings, the staff would play Scrabble or perch at the bar and talk, and it was on one of these slow nights that Rob, the manager, and I hit upon the idea of an airship.

We were staring into space, I remember; talking about the bar.

At this point the bar was one of the few places in the school where students could exhibit their work, and the walls, ledges and large windowsills were crammed with sculptures and paintings. A huge canvas by Bill Drummond hung on one side of the hall which said GET YOUR HAIR CUT, one of a series of works the artist had lent to Rob to display in the bar. I think Rob and I were talking about this as we stared up into the eaves, discussing GET YOUR HAIR CUT, the student art on show, the roof – our conversation spinning off at intervals but always arcing back to large student work and the roof space.

That morning I had been exploring Norwich and discovered the brass plaques on the doors of City Hall which depict the history and trades of the town. One showed an engineer working with a propeller – a reference to the firm Boulton & Paul Ltd, a general manufacturing firm which built aircraft and airships among other things.*

Talking to the art school caretakers about the doors later that week I was told how Boulton & Paul Ltd had won the contract to construct the frame of the fateful R101 airship in the 1920s, then the largest aircraft ever built.* One old boy recalled being held aloft as the ship flew over Norwich on a test flight.

‘The whole city stopped to watch it circle and pass. Everyone was out in the streets.’*

Maybe R101 was circling and passing through my mind that night because the conversation about GET YOUR HAIR CUT, student work, and the roof came to rest on me, suggesting the construction of a large-scale airship above the bar. That would be brilliant, we agreed; and then went back to staring into space.

• • • • •

A week passed. I knew Rob had probably forgotten about our conversation and I still had every opportunity to forget it too and walk away, but the seed was sown and the space was there, waiting. I couldn’t look up any more without seeing the negative space of a large, ominous airship hanging there, goading me.

• • • • •

A month into the winter term I had drawn and researched to a point where I’d some idea of the airship’s size. I wanted the balloon to loom in a big room and as such it would have to be large. Six metres long, perhaps; over a metre in diameter. Also, it would have to be light so as to hang from the trusses without causing damage and, most importantly, look right. If weighty and over-engineered it would look wrong, I knew – it had to appear to float. Wood and paper, then – flexible, strong woods covered in paper like a kite.

However, it became clear that there wasn’t the space for me to build it in the art school workshops. I remember I sought out a technician and we paced the airship out; too big. Not that there seemed a surfeit of students making massive wooden things; not that there seemed much being made at all – the wood workshops seemed principally employed to make canvas stretchers and the main wood of choice appeared to be ‘ply’.

My rough notes about the ‘springing/laminate potential of beech and birch’ were met with polite concern. I was pointed towards the birch ply and chipboard.

‘That’s not really wood, though, is it?’ I asked the technician.

I think he took that rather hard.

I decided to let it lie.

Within a week it wasn’t the woodwork which concerned me as much as the people coming out of it to ask why I, a student on a two-year part-time writing MA, wanted to build things at all.

• • • • •

I am writing this introduction a couple of years after the events I’m describing and it’s strange to think now but my idea of an art school can’t really exist any more. The new fee system introduced after my time in Norwich has brought an end to the idea of studying with an open mind ‘just to see what happens’. I don’t think you can really do that if you’re paying £30,000.

The notion of value has shifted and the vocational is king once more. To pay out so much ‘just to see what happens’ seems decadent; the fees will surely cost out those unsure of what they want to become, or looking for an adventure.

Jarvis Cocker expressed the idea well:

‘As much as I wanted to study something, I went to Saint Martin’s because I just wanted to get out of Sheffield. I just looked at the colleges and it said, “This one is on Charing Cross Road”, so I thought, “Great, three years in Soho. Summat’s going to happen.” And it did.’*

To arrive in a space and be inspired to make art by its fabric and atmosphere – if I’d been asked what my ideal of an art school was before I arrived in Norwich, that would have been close … but maybe we’ve moved into a post-impulsive airship epoch.

Today, all government funding cut, I note the school has closed down my course and moved towards a more logical, verifiably employable roster of subjects – the abstruse hinterlands of Fine Art and Sculpture squeezed in favour of the more honest fare of Fashion, Graphic Design and Animation; a white sea of Macs sweeping all before it.

But let’s return to the winter of 2006 and the wood workshop where I’m not going to work and look around. There are tools here. The ones on show are old and battered. The better ones are locked away, we’re told, because otherwise they’d walk. Security is a problem and the technician cannot be everywhere at once, so the available kit walks and the rest is kept hidden.

Paranoia permeates the space and I feel bad for the technician, who’s doubtless doing his best but he’s under pressure and having to take on responsibilities beyond his original remit. In this context it’s reasonable to suppose that writers on part-time MAs talking about ambitious zeppelin projects would be given short shrift. He has to be there. He’s put upon. He’s busy. I bet he had people in there ‘talking’ all the time. Time wasters, charlatans, and opportunists – out to nick the shiny G-clamps, light-fingered magpies with asymmetric haircuts. Bastards to a man!

Now, it’s all very well writing this down with hindsight and retrospect and all the other tools available after the event – indulging in a bit of the third person to suggest a distance between now and then, the school and me, the technician and me – but it’s important to say that I didn’t help my cause.

I don’t like confrontation. Hate it. I felt plywood wasn’t the way to go and should have stood my ground, but it was much easier to smile along and nod and agree we should order a load of it and then run away; it was the hiding for the next two years which proved tricky, especially since the wood workshop stood at the entrance to one of the main buildings at the school and I knew I’d upset a man with a large collection of hammers.*

• • • • •

In early 2007 I travelled down to Henley-on-Thames to ask a pair of boat builders how best to construct an airship.

En route to London, the previous week, I’d spoken to my father at length about the project and he’d suggested that to question received wisdom, to experiment, fail and learn, was the point of a degree. Better to fail on your own terms than be led astray and compromise:

‘You know, you’ll spend ages building it out of the wrong stuff to please someone else, it’ll go wrong and you’ll end up smashing it up with an axe, or something …’ he pronounced near Heston Services, adding, ‘You’ve made your bed now anyway.’ *

• • • • •

Colin Henwood and Richard Way know about wood and their knowledge is deep. At our first meeting we sat in the shed at the heart of their yard and talked around the airship – unpacking each possible solution, weighing the ways it could be done. This took quite some time since it turned out I had many options – different woods, fixings, joints, glues; each with their own character and peculiarities.

Their enthusiasm for the project, my doodled sketches and the mooted materials spilled out along tangents and into stories about craft.

At that first meeting, Richard spoke of his work with wood and boats, his tools and concerns, with a love and mesmeric intensity that affected me deeply and has subsequently shaped this book. He put the idea in motion that people who love what they do, are immersed and consumed by their work, are wont to speak about it with an engaging and infectious generosity. There was no cynicism when he spoke, just a simple clarity of thought, of process and labour, and this was to set a pattern for many subsequent exchanges I was to have; in fact it’s largely due to Richard’s enthusiasm and lucidity that I went out and sought those exchanges at all. I’d taken along a rudimentary Dictaphone to record our chat – and it was to be a chat, a casual meeting for which I’d made no notes other than rough drawings and annotations in my journal. I suppose I imagined I’d be there an hour or two. But two hours turned into four, and lunch, and as dusk fell we three were still talking. I didn’t want it to end, it was such a pleasure. When I got home I transcribed the tape and happily listened to the day over again.* Below is a little of our conversation, beginning with Richard describing his daily routine:

‘I start at half past seven during the week and finish at six o’clock. I used to work much longer. My first experience of boat building was working at a time when there was much too much work and not enough people so we used to work through till ten o’clock at night or one o’clock in the morning and that went on month after month so I got very used to terribly long hours. You can’t do that when you get to my age, it just becomes too exhausting.’

What age were you when you started?

‘I was twenty-one. It was tiring but at that age you can do enormous amounts of work and still get up the following morning and do it again. Young people are always half out of control anyway, aren’t they? (Laughs)

I discovered shortly after I started that I much preferred using tools that had been used before. It wasn’t a conscious decision to begin with but … I can feel a lot through my hands. I’ve got a very delicate sense of feeling and just felt that new tools were very sharp, all their edges were very sharp, and I much preferred buying old tools that were quite worn but still very usable.

You always buy some things new because you want the full length of a long paring chisel, for example, but gradually I’ve swapped over all the ones I bought new for older ones I’ve found. It didn’t become an obsession, thankfully, but I decided that I liked knowing about tools, so I read a lot of books and I used to buy tools when job-lots came up at local auctions, and sometimes I’d get them from people I knew, so that meant I’d tools that reminded me of the man who owned them before. I’ll pick a tool up and think, “Ah, that’s Pat Wheeler’s – the old boy who lived in the village.” It brings a picture up in my mind which is rather fine and it’s nice to know that your tools have done other work, you know; generations of work.

At home in my workshop, I’ve tools that are centuries old – Georgian chisels, things like that, and they’re absolutely magnificent. I’ve got Georgian wooden planes, braces, and drills, extraordinary things …’

At this point Colin pointed ruefully to Richard’s toolbox – a blanket box on caster wheels – a hefty laden chest:

‘As you can see, Dicky hasn’t brought very many tools with him today …’

And as we laughed I became aware that the scope of my project was opening out, alive in the room, after so many months of being closed down. I was engaged with people who knew what they were doing. The spectral airship flew here too – more than that – buoyed by enthusiasm, it lived.

For the next few months, every chance I got, I travelled home to Bristol to build the ship of my imagination – 200 miles from the art school bar as the crow flew.

The body of an airship is a collection of variously sized hoops fixed together with cross braces – dirigibles generally have a keel like a boat, their skeleton frame distinguishing them from blimps, which are essentially bags that use gas pressure to maintain their shape.

To start with I set about making twenty hoops of various sizes – each as thin and strong as possible, each formed of three or four layers of beechwood. Beech has a fine grain which lends it a strength and flexibility suited for shaping and moulding – for this reason it is used a great deal in furniture making. I built up a laminate sandwich of wood/glue/wood/glue/wood around circular template formers, each a slightly different diameter – clamping each complaining lath length tight until it set, before adding the next.* My first efforts were fairly awful but gradually I learnt what I was doing and the hoops began to take a more uniform, circular shape.

Successful rings were laid out on the floor like ripples; pear-shaped failures were taken outside and burnt.

While laminates dried in their jigs, I moved on to the nose and tail. Again, this was trial and error and the thought that it was all going to fall apart or bow (and then fall apart) was never far from my mind; but I was fathoming the beech and coming to respect its toughness. Once layered up and glued into shape it was steadfast. The material didn’t lie. When I botched I couldn’t blame the beech, which often called my bluff; refusing to be undone – wood and glue having become a sturdy third thing – hoop or half-uncoiled mess.

Four tailplanes were measured and marked on board, sawn up, sanded and slotted together – aerofoil ribs fixed at regular intervals looking beaky and svelte.

The dust was flying from the bandsaw blade, sketched revisions and tea stains filled my notebooks, and solvents daubed my boiler suit and stunk out my hair. At the end of each day, on the train journey home, I’d peel PVA from my hands.

The nose cone went together fairly quickly with a similarly slot-oriented approach to the fins – the profile of the front dome built up in segments to form a pointy jelly mould, a hollow cupola built around the smallest of my beech hoops; a card skinned nib.

An assembly frame was made on which to build the kit of bits. Thin stringer laths were cut to fix across the hoops and form the rigid frame – skeleton cigar … late nights listening to the radio, sugary tea and pencil shavings – ticking off the parts lists until early summer, when I packed up the airship like a pasta tangram into a Volvo Estate.*

My MA, meanwhile, was going well. I was writing strictly relevant pieces for my course and moonlighting with zeppelins the rest of the time.* As the first year finished and the long summer break between the first and second year stretched ahead, I was setting out my kit in the union bar, ready for the build.

Up went the frame with its central jig. On went the hoops, held by spars. Everything was clamped and cable-tied at this point since nothing was straight or square.

This part of the project was time-lapse filmed for posterity and the early footage shows me deploying tape measure and spirit level with enthusiasm. Lying on my back beneath the fuselage, head scratching, wandering off, wandering back with tea and a pencil, losing and hunting for the pencil, making notes, fiddling with string; like Buster Keaton … that was week one.

Week two saw the keels* glued into place and the tail cone taking shape.

Week three was a bit of a write-off since I spent much of it undoing laths stuck into place under the influence of Guinness Export. The wrong place. Wonkily.

The nose was fixed in week four and the rest of the stringers followed. Because of the ship’s size, lath strips had to be seamed together at intervals with scarf joints, the two lengths cut with a taper and joined to form a continuous span. The scarfs were positioned at intervals so as not to create weak spots in the frame.

Week five, the tail fins went on; the central spars were cut and removed. The ship was carried off the stage and hung from its top keel for the first time, swinging slightly on its new jib. The team of bar staff who’d helped me lift and relocate it stood back.

‘Bit big, isn’t it?’ said Rob, looking warily up at the beams, and it was true; away from the stage and out in the room the airship did look massive.

‘Don’t worry,’ I reassured him, ‘I’ve done some maths and it only weighs as much as your legs.’

This seemed to settle him down.*

• • • • •

All the time I was building the airship, especially in those final weeks, I was distracted. A couple of years later, Stewart Lee nailed the feeling:

‘You often don’t realise that you’re working on something in your head until it’s formed – you might have had something that you thought you were doing for fun or was just interesting to you but suddenly you realise that it’s all adding up into the shape of an idea.’

Now built – out of my head and over there, causing Rob to fret about the beams – I saw the airship as a manifest preoccupation.

It wasn’t just an airship built on a whim; it was a reaction – an elephant in the room – everything the art school seemed to be turning away from;* a large, ambitious, crafted wooden piece of work which mirrored and celebrated the building around it, inspired by the ghosts of the city. I believed in the fabric of the bar and school and wished to celebrate that. The building was benign, inspiring and positive; it was the people at the top who concerned me.

Looking down the beech laths at the scarf joints, I felt the calm assurance of the materials and saw the influence of Richard and Colin in Henley-on-Thames and my father back in Bristol. The airship had put me in touch with them and articulated their knowledge better than words. The process was a language, lucid and succinct. It had an integrity.

I had faith in the wood and glue.

On 15 August 2007 I made the following note in my diary:

Today the bar paid for a set of ropes and pulleys and hired a scaffold tower.

I keep finding notes I’ve written about ‘People who know what they’re doing.’

I work here, in this room. The airship is site-specific.

The room is the space I respond to.

Does this happen to other people?*

• • • • •

The scaffolding tower was assembled one weekend shortly before the start of the new school year. From the top it was clear that the eaves were a lot higher than they seemed from the bar far below. Three of us scaled the gantry to hang ropes and thread the pulleys and shortly afterwards the airship was winched into the air for the first time accompanied by a blast of ‘When the Levee Breaks’.*

It was up.

From beneath, its lines merged and intercut the wood of the roof, putting me in mind of Orozco’s Mobile Matrix, a suspended whale skeleton,* and as the concentric graphite circles drawn on those bones radiated out, overlapped and distorted, so the beams moved through the cage of beechwood above our heads now. The few of us there in the moments after it was raised walked up and down below as the airship swam.

Later I sat on the stage at the back of the hall and looked at it for an hour or two, watching it settle in the ropes. It was up; unpapered and naked for now but that could be addressed over time.

But the important thing, as Rob pointed out, was that the stage was now freed up for the pool table because, say what you like about arty kids in an arty bar, they loved their pool: ‘You know, given the choice between an arty airship and pool …’

Luckily such a nightmarish choice was never forced upon them.

The new term started and I went back to my MA, papering the airship on Sunday mornings with tissue paper donated by Habitat.* I was helped in this task by Virginie Mermet, a brilliant French girl.*

We’d arrive early and open all the windows to ventilate the stale ale air before making tea and lowering the airship down. Tissue was cut into strips and applied with aircraft dope – a varnish that tautened and strengthened the paper as it dried while giving us headaches and mild hallucinations.

During these mornings we’d talk about ideas of artists and space and listen to Klaus Nomi.* Virginie was of the opinion that all artists create and respond to a space, be it site-specific sculpture like the airship or an environment attuned to making work. We spoke about photographs we’d seen of Francis Bacon’s studio and Roald Dahl’s shed, concepts of theatre and atmosphere; the idea that a resonance of creativity can remain in a building long after the people have gone and the function altered.

Kitchens, boat yards, studios, halls, sheds, rehearsal rooms, cellars, theatres, roofs, gardens, landscapes, vehicles – inspiring and facilitating artistry.

Some spaces must bear witness to a process while others stimulate it – become steeped in it. While some buildings evolve over decades into a perfect working environment, others are built for that purpose from scratch, others will be a compromise; some permanent, some fleeting, some known about and public, some private, even hidden.

That night as an experiment, I wrote a few pages about the broadcaster John Peel. Under the heading ATMOSPHERE, I recalled my second-year house at university; Thursday night, a large cold bedroom where the living room should have been. A desk, a set of shelves, a dicey gas fire, a bed, a wardrobe.

I’m sat at the desk in a thick jumper, illuminated by a balanced-arm lamp and the flicker of a radio set handed down from my mother – bought during the three-day weeks of the seventies because it could take batteries.

I’m listening to John Peel.

Thursday was not a pub night, Thursday was the night John broadcast his programme direct from his Stowmarket home, Peel Acres. Thursdays were sacrosanct. I remember taping Mono, The Black Keys and Four Tet sessions, listening with my finger hovering over the red button on the deck.

My diary of 13 May 2004 records that John played four session tracks by The Izzys and I enjoyed them very much. He opened the show with the greeting ‘Hello, brothers and sisters, and welcome to Peel Acres’ – very much the spirit behind those Thursdays; he was welcoming the audience into his home, where he sat playing tracks he thought we might like to hear – something new. Something by Jazzfinger or The Fall, say; the jet-wash of Part Chimp or The Izzys in session covering Richard and Linda Thompson.

Amazing to think how intimate it all felt – a man in his house in conversation with the world but broadcasting to you. A public service.

I remember the quiet of my room then, the crackle of the radio and the feeling of connectivity.

John Peel died in October 2004.*

In 2008 I wrote to his wife, Sheila Ravenscroft:

‘Perhaps the most interesting spaces grow up and around the person working within them. The longer this project* goes on, the more I think of John’s programmes from Peel Acres and recall the way the atmosphere of his studio seemed to percolate out into my room; the wonderful conversational way he had of speaking, how it fostered a world and set of associations that continue to inform what I’m writing today.’

• • • • •

In his book Waterlog, Roger Deakin describes a seemingly impossible swan dive made by a market-worker in the 1920s from the copper turret of the Norwich art school, over Soane’s St George’s Street Bridge and into the River Wensum.

A friend lent me the book towards the end of my degree and I raced through it, drinking up the words on water, wild swimming and landscape. A few minutes after discovering the Norwich nosedive passage, I was stood on the same bridge, text in hand, eyes skyward, trying to join the dots – turret, bridge, river. Copper, sky, Wensum – but the orbit did not fit.