Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «A Country Girl»

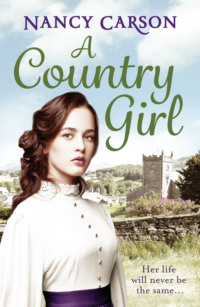

NANCY CARSON

A Country Girl

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by AVON 2017

Copyright © Nancy Carson 2017

Cover design © Debbie Clements 2017

Nancy Carson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008173548

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008134877

Version: 2018-01-09

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Author’s Note

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author:

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

‘Aye up, the Binghams are coming through the lock,’ Kate Stokes cried provocatively, knowing it would rouse Algernon, her brother, from his sun-induced reverie.

As soon as she’d heard the clip-clop of a horse’s hoofs and attendant voices, Kate had rushed to peer over the garden fence to see who was on the towpath of the canal which ran alongside. There was some personal motive in this, too – it could have been Reggie Hodgetts. Till that moment, she had been stooping down to tend their father’s vegetable patch, creating the illusion that she was a homely girl, which she patently was not. She was, however, extraordinarily pretty but with a tongue like a whip, and her relationship with Algernon was, at best, thorny.

Algernon had seemed unflappable as he leant against the back door of the lock-keeper’s cottage where the siblings lived with their mother and father. His face was sedately and serenely turned upward to receive the warmth of the spring sun. But, on hearing the news that the Binghams were coming through the lock, his heart missed a beat and he was at once stirred into a renewed vigour. The Binghams, you see, had a particularly lovely daughter, and he duly rushed to the fence to join Kate to gain sight of her. Sure enough, he spotted Seth Bingham leading his strong little horse as it pulled their pair of narrowboats towards the lock gates.

Kate flashed a knowing look at her brother. ‘I thought that might get you going.’

‘Why should the Binghams get me going?’ he protested, feigning indifference. ‘You were pretty quick off the mark yourself … to see if it was the Hodgettses, I reckon.’

‘The Hodgettses ain’t due past here till Tuesday.’

‘No, but you sprang up quick enough, just in case it was that scruff Reggie,’ Algernon countered. ‘So you’ll just have to wait till Tuesday, won’t you, before you can go gallivanting off with him?’ He glanced at his sister disdainfully. ‘Reggie Hodgetts ain’t much of a catch, is he?’

‘Mind your own business,’ Kate replied, at once rallying. ‘You’re interested enough in Marigold Bingham, the daughter of a scruffy boatman. I’ve seen you. Every time she comes a-nigh you’re up, ogling after her. You can’t keep your eyes off her.’

Algernon – who answered more readily to Algie – replied calmly, ‘She’s different. She looks nice. She’s got something about her. I’d like to see her without her working clothes on.’

‘Pooh, I bet you would, you dirty sod—’

‘I didn’t mean that. I mean I’d like to see her in her Sunday best—’

‘Huh!’ Kate exclaimed suspiciously. ‘I know what you mean. And you’m already a-courting Harriet Meese … You ought to be ashamed.’

‘Ashamed?’ he protested defensively. ‘Why should I be ashamed? I ain’t promised to Harriet Meese.’

‘You could do worse.’

‘And you could do better,’ Algie replied, as he scanned the towpath opposite for sight of Marigold.

‘Oh, well,’ remarked Kate loftily, ‘We all know Harriet’s face ain’t up to much.’

‘Neither is yours,’ Algie responded with brotherly disparagement. He would never let Kate believe he considered her nice-looking.

Kate reacted by bobbing her tongue at Algie, but he ignored her and watched the progress of the Binghams. Hannah Bingham, Seth’s wife, was at the tiller, steering the horse boat, the leading one of the pair which they used for their work. Hannah, he perceived, was not like the usual boatwomen. For a start, he had an inkling that she was not narrowboat born and bred. She did not wear the traditional bonnet of the boatwomen, which fell in folds over their shoulders and back, like a ruched coal sack, and which was about as appealing. She had large, soulful dark eyes, and was blessed with high cheekbones; a handsome woman still, who must have been a rare beauty in her youth. The Binghams seemed a cut above many of the boat families. Their boats were spruce and shining, and always looked freshly painted with the colourful decorations that were traditional among their kind. They obviously took care. They stood out.

A child was crawling at Hannah’s feet, tethered with a piece of string to prevent him falling into the canal. Various other sons and daughters, all youngsters, watched the proceedings, scattered randomly aboard the second narrowboat which they towed, known as the butty. A lark hopped about in a bamboo cage, set between tubs of plants which stood like sentries on top of the cabin.

‘I can’t see Marigold,’ Algie complained. ‘Is she there?’

‘There …’ Kate pointed impatiently. ‘Opening the sluice. Hidden by the hoss …’

He shifted along the fence and caught sight of Marigold Bingham bending over the mechanism, a windlass in her hand as she deftly opened the sluice that let water into the lock. Her dark, shining hair was pinned up, giving an elegant set to her neck. Algie was glad she never seemed to wear those hideous bonnets either. He waited, his eyes never leaving her until he was blessed with a rewarding glimpse of her lovely face. She walked jauntily back towards the boat swinging her windlass, the breeze pressing her thin dress against her body, outlining her youthful figure and slender legs. She patted the horse as she went, and Algie basked in the sunshine of the smile that was intended for her father.

‘How do, Mr Bingham!’ Algie called amiably, rather to draw Marigold’s attention than Seth’s. ‘And you, Mrs Bingham.’ He touched the peak of an imaginary cap as a mark of respect.

Seth Bingham turned around and addressed himself to Algie, whose face was bearing a matey grin as he peered over the lock-keeper’s garden fence. ‘How do, young Algie. It’s a fine day for it and no mistake.’

‘Mooring up here for the night, Mr Bingham?’

‘Soon as we’m through the lock, if there’s e’er a mooring free,’ the boatman replied. ‘It is Sunday, lad, after all’s said and done.’

‘God’s day of rest, they say.’

Seth scoffed at the notion. ‘For some, mebbe.’

To Algie’s delight, Marigold flashed him a shy smile of acknowledgement. He saw a hint of her mother in her lovely face.

‘How do, Marigold.’

‘Hello, Algie.’ She answered coyly, avoiding his eyes further as she stepped onto the butty.

Their strong little horse took the strain, stamping on the hard surface of the towpath to gain some purchase as it hauled the first narrowboat, the horse boat, slowly into the lock. Steadily, surely, the narrowboat, lying low in the water under the burden of its cargo, began to inch forward away from the side of the canal. Marigold had nimbly jumped aboard and was at the tiller of the butty now, waiting for her turn to enter the lock.

Algie watched, unable to take his eyes off her. She was as statuesque as the figurehead of some naval flagship, but infinitely more lovely. Her back was elegantly erect, her head, which he beheld in profile now, was held high, showing her exquisite nose to wonderful advantage. He reckoned Marigold was about eighteen, though he did not know it for certain. For years he’d kept an assessing, admiring eye on her, catching occasional glimpses as she passed the lock-keeper’s cottage. In the last three years he’d noticed how her looks and demeanour had really blossomed. It was as if he’d been patiently watching the petals of a slow-blooming rose unfurl into flawless beauty. She stood out from the other boatmen’s daughters; always had. In fact, she stood out from all the other daughters of men, boatmen’s or not. She was endowed with a natural grace where others seemed ungainly. If girls like Marigold, who lived and worked on the canals, hadn’t escaped to work in the factories by the time they were eighteen, it was generally because they were wed to a boatman, some by the time they were sixteen. Yet there was never anything or anybody to suggest that Marigold was spoken for. Maybe Seth was too protective of her, realising her worth, saving her for somebody with finer prospects. It would not surprise him.

‘You look a picture today, Marigold,’ Algie called, giving her a wink. ‘In your Sunday best, are you?’

She smiled shyly and shook her head as the butty slid forward. ‘Just me ornery working clothes, Algie,’ she answered in a small but very appealing voice.

‘Then I’d like to see you in your Sunday best. I was just saying to our Kate—’

‘Algie! Kate!’ Clara Stokes, their mother, was calling from the back door. ‘Your dinners are on the table. Come on, afore they get cold.’

Algie rolled his eyes in frustration that his attempt to get acquainted with the girl, his intention to flatter her a little, was being thwarted at such a critical moment. ‘I gotta go, Marigold. Me dinner’s ready. See you soon, eh?’

‘I expect so.’

He hesitated, aware that Kate was already making her way across the garden to the cottage. ‘Are you due down this cut next Sunday, Marigold?’ he asked when Kate was out of earshot, endeavouring to sound casual.

‘Most likely Tuesday, on the way back from Kidderminster.’

‘That’s a pity. I’ll be at work Tuesday. I shan’t see you.’

Marigold smiled dismissively. It was hardly of grave concern to her. Yet she wondered if his questioning her thus meant he was interested in her. The thought at once ignited her interest in him and she looked at him with increasing curiosity through large blue eyes, hooded by long dark lashes.

‘So when shall you pass this way again on the way to Kiddy?’ he persisted.

‘Dunno,’ she replied, and he noticed that she blushed. ‘We might not be going to Kiddy for a while. We might be going up again’ Nantwich or Coventry. It depends what work me dad picks up.’

‘Course …’ He sighed resignedly. Yet her blush somehow uplifted him, and he wallowed in the wondrous thought that he might appeal to her too. But he had to go. His dinner was on the table. ‘Ta-ra, then, Marigold. See you sometime, eh?’

She smiled modestly and nodded, and Algie strolled indoors for his Sunday dinner, disappointed.

‘Our Algernon’s keen on that Marigold Bingham, our Mom,’ Kate said over the dinner table.

‘You mean Hannah Bingham’s eldest?’

Kate nodded, unable to speak further yet because of a mouthful of cabbage. She chewed vigorously and swallowed. ‘Fancies her, he does.’

‘He’d be best advised to keep away from boat girls,’ Clara commented with a warning glance at her only son. ‘Anyroad, what’s up with Harriet Meese?’

‘Nothing’s up with Harriet Meese as I know of,’ Algie protested. ‘I just think as Marigold Bingham’s got more about her than the usual boat girls.’

‘Fancies her rotten, he does,’ Kate repeated, with her typical sisterly mischief.

‘So what?’ he said, irritated by her meaningless judgement of him and of his taste in girls. ‘There’s nothing up with fancying a girl, is there, Dad? It ain’t as if I’m about to do anything wrong.’

‘Just so long as you don’t.’

‘Chance would be a fine thing,’ Algie muttered inaudibly under his breath.

Will Stokes was, for the moment, more concerned with cutting a tough piece of gristle off his meat than heeding the goading remarks of his daughter. ‘Oh, she’s comely enough, I grant yer,’ Will remarked, looking up from his plate, the gristle duly severed. ‘But looks ain’t everything. Tek my advice and stick with young Harriet. Harriet’s a fine, respectable lass. She’ll do for thee. Her father’s in the money an’ all, just remember that.’

‘Money that’ll never amount to much if she’s got to share it with six sisters, come the day,’ Clara commented, as a downside.

‘Well, our Kate can talk, going on about me and Marigold Bingham,’ Algie said, aiming to turn attention from himself. ‘She often wanders off with that Reggie Hodgetts off the narrowboats …’

Kate gasped with indignation and blushed vividly at what her brother was tactlessly revealing. She gave Algie a kick in the shins under the table.

Noticing her blushes, Will eyed his daughter with suspicion. ‘’Tis to be hoped you behave yourself, young lady, else there’ll be hell to pay – for the pair o’ yer.’

‘Course I behave meself,’ she protested, glancing indignantly at Algie. ‘You don’t think as I’d do anything amiss, do you, Dad?’

‘I should hope as you got more sense.’ He wagged his knife at her across the table in admonishment. ‘Else I’ll be having a word with young Reggie Hodgetts. You’ve been brought up decent and respectable, our Kate. Tek a leaf out o’ your mother’s book, that’s my advice. There was never a more untarnished woman anywhere than your mother. That’s true, ain’t it, Clara?’

‘I had to be,’ Clara replied, conscientiously trimming the rim of fat off the only slice of roast pork she’d allowed herself. ‘Else me father would’ve killed me.’

Algie pondered his mother, trying to imagine her as a young woman being courted by his father. She had been a fine-looking young girl then, he knew it for a fact. For a woman of forty-two, she still held on to her looks and figure remarkably well. It was obvious from whom Kate had inherited her looks and figure, which the local lads found so beguiling.

He finished his dinner quietly, deeming it politic to add nothing more to that mealtime conversation. His thoughts were still focused on young Marigold Bingham. He’d noticed her blushes as she’d spoken to him and he wondered … Algie was in no way conceited, and he rejoiced in the thought that maybe he had aroused her interest. If so, it was the greatest event of his life so far. Damn his dinner being ready at exactly the moment when he was about to get to know her a little better. Right now she and the rest of the Binghams would be moored in the basin outside. So frustratingly close …

So conveniently close …

There was a knock on the door. One of Seth Bingham’s younger children had come to pay the toll for passing through the locks. Algie waited. His mother moved to clear away the gravy-smeared plates, cutlery, pots and pans, which she stacked in an enamelled bowl. When she and Kate were in the scullery washing them, and his father was sitting contentedly in front of the parlour fire with his feet up and his eyes shut, attempting his Sunday afternoon nap, Algie silently and surreptitiously made his exit …

Although Algernon Stokes was twenty-two and a man, yet still he was a boy. Or, more correctly, a lad. His view of the world had not yet been tainted by its artificiality and pretence, so he lived life, and looked forward to what it offered, with a naïve enthusiasm that emanates only from youth. He was largely content. His upbringing had been conscientiously accomplished by a strict yet fair father’s influence, endorsed and abetted by his mother, although she still followed him around the house dutifully tidying up behind him. His sister Kate was tiresome, though, a bit of an enigma to Algie, and a nuisance to boot. Algie was utterly fascinated with girls in general, yet absolutely not with Kate in particular.

He had drifted into a sort of half-hearted courtship with a girl called Harriet Meese, only because she had shown an interest in him in the first place, an interest which flattered him enormously. She was not his ideal, however, hence his half-heartedness. His ideal girl was beautiful of face and figure, utterly desirable and unresisting, even prepared to risk ruin by submitting to his sexual endeavours; qualities he believed he might find in Marigold Bingham. Many young men his own age were married, some had even fathered children already, and Algie envied their access to the sensual pleasures they must all enjoy in their marital beds, for such pleasures had always been denied Algie. The thought of spending the rest of his life in celibacy horrified him, but from his point of view, it looked as if he was destined to, unless he could nurture some girl who appealed to him physically, and who would be unreservedly willing. Thus, he had become preoccupied with finding a solution. It boiled down to this: he was twenty-two already, but he hadn’t lived. Therefore, he might as well still be seven.

Marriage would have offered a solution, but not marriage to Harriet. Oh, most certainly not to Harriet. He would not rule marriage out completely, though, if the right girl came along. On the other hand, why not simply bypass the institution of marriage altogether? The world offered too many pretty girls to have to settle for just one, especially one whose face was particularly uninspiring, as Harriet’s was. He knew from hearsay that there were plenty of girls willing enough to partake of those delectable stolen pleasures for which he yearned, if only such girls were not so damned elusive. He was thus inclined to believe they all inhabited another planet. They never seemed to pass his way at any rate. Even if they did, he would hardly be able to recognise such qualities in them as he was seeking, and why would they look at him twice anyway? He was nothing special, or so he thought. He did not like his own face, he did not like his dark, curly hair, nor his tallness, nor the shape of his nose either. How could he possibly appeal to women? Especially the sort of women that would interest him, who just had to be pretty, with appealing, youthful figures. Otherwise there was no point to it.

That same spring Sunday afternoon in 1890 was one of those delightful, lengthening days which herald the approach of summer. Soft sunlight caressed distant hills, and already the air, bearing the sweet smell of greenness, had a mollifying summer mildness about it. A warm breeze gently flurried the fresh crop of young leaves that bedecked the trees after their long winter nakedness. A flock of pigeons flapped in unison overhead, wheeling gleefully across the blue sky in celebration of their Sunday release into glorious sunshine.

The lock-keeper’s cottage was situated alongside the Stourbridge Canal at an area called Buckpool, set between the township of Brierley Hill and the village of Wordsley, yet no great distance from either. The warmth of the spring day cosseted Algie as he stepped out into it. He stopped to appreciate it, closing his eyes, wallowing in the sensual touch of sunlight, a touch too long denied him. For a fleeting moment, he allowed himself the luxury of a sensual thought; that of spooning in the long grass of some secluded meadow with Marigold Bingham. He’d had his eye on her for so much longer than he would care to admit.

Hannah, Marigold’s mother, saw him and waved amiably.

‘Still having your dinners?’ Algie called, disappointed that he’d mistimed his appearance and they hadn’t finished.

‘You gotta eat sometime,’ Hannah called back. ‘Even on this job.’

‘I’m just on me way to the public.’ He felt it necessary to explain his presence, even though the explanation was an instantly conjured lie, in case Marigold, who could be listening, might rightly presume that he was seeking her and decide to avoid him. ‘I just fancy a pint after me dinner.’

‘You’ll very likely see Seth in there.’

‘That’s what I was wondering,’ he fibbed.

‘He always likes a pint or two afore he has his Sunday dinner.’ She said the word afore as if she considered it strange that Algie should want to drink beer after his dinner. ‘I don’t mind keeping it warm in the stove till he gets back. He likes the beer at the Bottle and Glass, you know. It’s why we moor up here when we’m this way.’

‘I might see him inside then.’ Algie smiled openly, hiding the disappointment at his inability to speak to Marigold without making his intentions obvious to her mother, and continued on the route to which he’d unthinkingly committed himself.

He walked the few yards to the next lock, which lay beneath the road bridge. There, he left the canal, crossed the road to the public house and entered the public bar. Inside, he leaned against the varnished wooden counter and greeted the publican, Thomas Simpson, familiarly. He ordered a tankard of India pale, peering for a sight of Seth Bingham through the haze of tobacco smoke. Seth was sitting on a wooden settle that echoed the shape of the bowed window, in conversation with two other men whom Algie recognised as boatmen also. They acknowledged him, but he thought better of getting drawn into their company, for it was likely to cost him the price of three extra tankards. He decided to give himself fifteen minutes to finish his beer, by which time he imagined Marigold would have finished her dinner. Then he would try again to catch her while her father was still supping and, perhaps, her mother’s back might be turned.

The huge clock that adorned one wall had a tick that sounded more like a clunk, even above the buzz of conversation, and Algie watched its hands slowly traverse its discoloured face. He drank his beer, trying to appear casual and unhurried, as if he was really enjoying it. He dropped the occasional greeting to various men who approached the bar for their refills, and took a casual, benign interest in a game of bagatelle other men were playing.

Eventually, he stepped outside once more into the unseasonably warm sunshine of the late April afternoon. At the bridge he hesitated and, for a brief second, watched the sun-flecked sparkle of the water as it lapped softly against the walls of the canal, plucking up the courage to approach Marigold again. He looked for the Sultan – the name given to Seth Bingham’s horse boat – and saw Marigold conscientiously wiping down the vivid paintwork of its cabin with a cloth. It was now or never, he thought as he rushed onto the towpath and approached.

‘Busy?’ he asked, beaming when he reached her.

She looked up, momentarily startled, evidently not expecting to see him, and smiled when she realised it was Algie Stokes again. ‘It has to be done regular, this cleaning,’ she replied pleasantly.

Up close – and this was as close as he’d ever been to Marigold – she was even more lovely. Her skin was as smooth and translucent as finest bone china. Her eyes seemed bluer, clearer, and wider; her dark eyelashes so unbelievably long. Her lips were upturned at the corners into a deliciously friendly smile, and he longed to kiss her. The very thought set his heart pounding.

‘Your two boats always look sparkling,’ he remarked with complete sincerity. ‘I’ve noticed that many a time.’

Marigold smiled proudly. ‘It’s ’cause me mom’s so fussy. She don’t want us to be mistook for one o’ them rodneys what keep their boats all scruffy. And I agree with her.’

‘Oh, I agree with her, as well. Where’s the sense in keeping your boat all scruffy when you have to live in it?’

‘And while we’m moored up, what better time to clean the outside?’ she said with all the practicality of a seasoned boatwoman. ‘We’m carrying coal this trip and the dust gets everywhere.’ She rolled her eyes, so appealingly. ‘You can taste it in your mouth and feel it in your tubes. It gets in your pores and in your clothes. It’s the devil’s own game trying to keep anything clean when you’m a-carrying coal.’

‘I can only begin to imagine,’ he replied earnestly, truly sympathetic to the problem. ‘I know what it’s like in our coal cellar. It must be ten times worse on a narrowboat. So you’re bound for Kidderminster, you reckon?’

‘Tomorrow. We’ll be on our way at first light.’

‘What time d’you expect to get there?’

Marigold shrugged. ‘It’s about dinner time as a rule. Then it depends if we can get offloaded quick. Some o’ them carpet factories am a bit half-soaked when it comes to offloading the boats, ’specially if you catch ’em at dinner time. Me dad likes to wind round and get back. He gets paid by the load, see? Me, I don’t mind if we get stuck there till night time. We do as a rule.’

‘Got much more cleaning to do?’

‘Only a bit. We’ve all got our jobs, but I’ve nearly finished mine for today.’

‘Fancy a walk then?’ Algie enquired boldly, seizing the moment.

‘A walk?’

He nodded. ‘I could take you a walk over the fields or up the lanes, if you like. You must be sick o’ looking at the cut all the time.’

She instantly flushed. ‘I’ll have to ask me mom.’

‘Ask her then.’ Algie’s heart skipped a beat. Marigold had agreed in principle. This was significant progress. All that stood in the way now was perhaps her mother.

Marigold smiled with blushing pleasure, and nipped inside the cabin.

Algie could no more help flirting with a pretty girl than some people can help stammering, but he had not the least intention of breaking anybody’s heart. For a start, he did not take himself seriously enough, he was not good-looking enough to succeed. The desire to elicit a smile from a pretty face was strong within him, however.

Hannah Bingham nipped out, holding a limp dishcloth. ‘You want to take our Marigold a walk?’ she asked, not unpleasantly.

‘If you’ve got no objection, Mrs Bingham,’ he answered with an apologetic but appealing smile. ‘She says she’s finished her jobs.’

‘I got no objection, young Algie, as long as she’s back well afore sundown.’

‘Oh, she’ll be back well before then, Mrs Bingham, I promise.’

‘Then you’ll have to give her a minute to spruce herself up if she’s going a walk.’ She turned and spoke to her daughter in the cabin. ‘Our Marigold, change into another frock if you’m going a walk with young Algie.’ She turned back to Algie and smiled. ‘Why don’t you come back in ten minutes when she’s ready, eh?’

Algie grinned with delight. ‘All right, I will, Mrs Bingham.’

He could hardly believe his luck. Marigold had agreed to accompany him on a walk, and her mother had sanctioned it. The prospect of getting the girl alone had, till that moment, seemed an improbable dream, but a dream he’d diligently clung to. He sauntered back to the lock-keeper’s cottage, thrilled. Maybe he had a way with women after all. Maybe he did possess some fascination or irresistible power over girls, despite his doubts. For so long he’d thought it unlikely. There was a suspicion meandering through his head – he knew not from where it came – that, in any case, a handsome face was not the be-all and end-all for women, but he just didn’t have the experience to know if it was true. For the time being, it was enough that some young women blushed when he spoke or smiled at them; and he made a point of smiling at all those girls who were pretty, whatever their station in life, rich or poor. If they thought he was ugly or uninteresting they could always turn their heads and ignore him. Yet they seldom did. Only the very stuck-up ones, and stuck-up girls he could not be doing with anyway.

He returned home to wait. Over the fireplace in the parlour was a mirror. He stood in front of it and looked at himself, but was not impressed. He straightened his necktie and tried unsuccessfully to smooth his unruly curls with the flat of his hand.