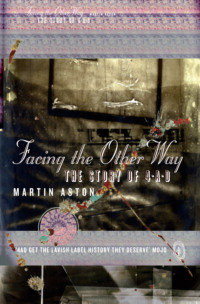

Czytaj książkę: «Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD»

Copyright

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

First published in Great Britain by The Friday Project 2013

Copyright © Martin Aston 2013

Martin Aston asserts the moral right to be

identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780007489619

Ebook Edition © September 2013 ISBN: 9780007522019

Version: 2015-12-03

ALSO BY MARTIN ASTON

Björkgraphy

Pulp

Acknowledgements

In the category of Indispensible, I have to start with Ivo Watts-Russell, for resisting his normal impulse to let the music alone do the talking, and for granting me so much time, commitment and unexpected copy-editing skills. And to Tate, Moke and Emmett, for their part in hosting me. To George, for his part too. Thanks also to Vaughan Oliver, for dedication and contributing extraordinary artwork. To Mat Clum, for his patience and endurance over the course. To the Mieren Neukers of Ladywell, for insight and encouragement. To my HarperCollins editor Scott Pack, for commissioning this book, and project editor Rachel Faulkner, editorial assistant Alice Tarbuck and copy editor Nicky Gyopari, for the finesse. To 4AD, especially Steve Webbon, Rich Walker, Annette Lee, Simon Halliday and Ed Horrox, for assistance/archive. To Madeleine Sheahan, for advice and Spanish translation, and Craig Roseberry, the one and only 4AD Whore – I know what this means to you. And finally, to three 4AD fan websites, Lars Magne Ingebrigtsen’s eyesore.no, Jeff Keibel’s fedge.net and Maximillian Mark Medina’s themysteryparade.com, for comprehensive listings.

Thanks to my two families – in London, Mum, David, Penny, Katie, Vicki and Christopher, Louis, Tess, and in Michigan, Mom Clum, Doug and family, Liz and family, Nate and Bruce, Mindy and Tom.

Many thanks to everyone I interviewed for the book, but especially Miki Berenyi, Mark Cox, Nigel Grierson, Robin Guthrie, Kristin Hersh, Robin Hurley, Matt Johnson, Brendan Perry, Simon Raymonde, Chris Staley and Anka Wolbert. Special thanks to John Grant and John-Mark Lapham, for sound and vision.

Thanks to my nearest-and-dearest: Brenda and Trish, Kurt, Mark, Pixie, Eloise and James, Sara, Will and Harriet, Merle and Gary, Joanna MLNOV, Laura, Yael, Meir and family, Duncan, Amanda, Madeleine, Mary Pat, Gordon, Catherine and Arvo, Nicole, Angela, Hop, Sarah and Foster, Cat my foxymoron, Dr John and Michael, Kat, Peter, Gabby and Trixie, Emma, Jessica and family, Clare and Antoine, Yas, Lauren and Sam, Jesper, Christine and Naomi, David, Yvette and family, Christina, Olivia and Bif, Patrick and Karl, Justin, Lisa and family, Cushla, Felicity, Dean and Britta, the Nervas, the Dutch, Jon and Patricia, Diana and Tim, cousin Jenny, Jim Fouratt, Steve, Mr Stroopy Mumblepants and Spencer, Bob and Jeff, Pat, John, Lynn, Siuin, Debbie, Jude, Sigrid, Amy, Laurence, Miriam and Viva, Jane, Richard, Huw and Dan, Edori and family, Susie and Mark, Lisa, and my Nunhead pals (Karolina, Lukasz, Hugo and Hannah, Claire, Andrew and Eva, John and Katrina, Carolyn, Jeremy and Max).

Thanks also to Tony Bacon, Ralf Henneking, James Nice, LightBrigade PR, José Enrique Plata Manjarrés and Andy Pearce, and to anyone I have inadvertently missed out, and also not credited for quotes, which I’ve done my upmost to do.

I finally want to thank Tim Carr, one of the insightful people I talked to for this book, and one of 4AD’s greatest supporters, in memoriam.

Dedication

This is dedicated to my father Basil, in memoriam, and to my mother Patricia. Thanks for not insisting I pursue a career in merchant banking.

To Moray, in memoriam. I hope you are grooving in your home disco, reading, writing and meditating, looking forward to tralaalaa o’clock.

Epigraph

Imagine a scene on a beach. A barbecue for friends and colleagues. Some of them like each other and some of them don’t. The man in charge, responsible for inviting them all, and responsible for feeding them, suddenly self-combusts. In his confused, mad dash to reach the water, to put out the flames, he ricochets into those closest to him and knocks them down, even starting minor fires over their bodies. Before he reaches the ocean, he passes through a pile of fireworks lying on the beach for use in a display later that night. All hell breaks loose, with everyone on the beach scattering, trying to save themselves. The man has now reached the water and finds he has gone out too far and has forgotten how to swim. He is drowning but unable to call for help. He is totally aware of the chaos on the beach that he is responsible for and has left behind but, because he’s drowning, can do nothing to prevent the destruction. He is puzzled as to why no one is coming to his rescue. Meanwhile, everyone to a man back on the beach is thinking, ‘You stupid cunt. What did you do that for, you’ve ruined everything’ and ‘For fuck’s sake, just swim’.

(George, 2013)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Also by Martin Aston

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

1 Did I Dream You Dreamed About Me?

2 Piper at the Gates of Oundle

3 1980 Forward

4 Art of Darkness

5 The Other Otherness

6 The Family That Plays Together

7 Dreams Made Flesh, but It’ll End in Tears

8 The Art Shit Tour and Other Stories

9 Le Mystère des Delicate Cutters

10 Chains Changed

11 To Suggest is to Create; to Describe is to Destroy

12 With Your Feet in the Air and Your Head on the Ground

13 An Ultra Vivid Beautiful Noise

14 Heaven, Las Vegas and Bust

15 Fool the World

16 A Tiny Little Speck in a Brobdingnag World

17 America Dreaming, on Such a Winter’s Day

18 All Virgos are Mad, Some More than Others

19 Fuck You Tiger, We’re Goin’ South

20 Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway

21 As Close as Two Coats of Paint on a Windswept Wall

22 Smile’s OK, a Last Gasp

23 Everything Must Go

24 Full of Dust and Guitars

25 Facing the Other Way

List of Illustrations

Illustrations Insert

About the Publisher

Introduction

When a fan of 4AD, and of the British independent label scene of the Eighties in general, heard I was writing this book, he asked me, ‘Is there much drama in the 4AD story?’

True, the story of 4AD doesn’t feature a TV presenter-cum-entrepreneur who starts a record label whose most iconic frontman commits suicide and initiates a Che Guevara-style cult; nor does it involve the decision to invest heavily in a nightclub that goes on to become an epicentre of the biggest dance music boom in UK history, rejuvenating both youth and drug culture, the combined legacy of which soon enough bankrupts said label.

That would be the suspenseful saga of Manchester’s Factory Records, 4AD’s principal peer in the world of pioneering, inventive and maverick independent labels. For both labels, the visual aesthetic was as crucial as the music, yet, in many ways, south London’s 4AD, formed in 1980, was the anti-Factory: its spearhead, Ivo Watts-Russell, was more of a recluse than a media-savvy self-promoter, and 4AD had no recognisable ties to the zeitgeist – nor to any cultural trend, in fact. All of that, Ivo felt, was irrelevant; only the artefact mattered – the music and its exquisite packaging. In the mid-Eighties there were constant references to ‘the 4AD sound’: a beautiful, dark, insular style. If the 2002 fictionalised film about Factory Records was called 24 Hour Party People, what might a film about 4AD be titled – Eight Hours Chilling, and Then Bed?

But whilst 4AD’s story may be less sensational and populist than Factory’s, it is equally gripping, the label’s A&R vision being that much greater, and its subsequent cast of characters even more fascinating and beguiling. Under Ivo, 4AD’s vision chimed with a rare era in British pop history when there was a sizeable market for innovation and experimentation. The artists he was drawn to were trailblazers, outsiders whose unique perspective invariably included a troubled, sometimes irreconcilable relationship with the mainstream (scoring the UK’s first independently released number 1 single was as much the beginning of the end for 4AD as it was the start of a new era), and with each other, like a dysfunctional family – and that includes the staff at the record label.

Like the motion of the swan’s legs beneath its ineffably elegant glide across water, below the surface of 4AD’s dazzling and enigmatic artwork and music the human drama unfolded. 4AD’s journey began as a shared discovery of a new world of sound and opportunity in the aftermath of the punk rock revolution. But its community was progressively fractured by splits, rivalries, writs, personal meltdowns, addiction, and depression – not least of the victims being 4AD’s most iconic artists Cocteau Twins, Pixies and The Breeders, and the label boss as well.

Though 4AD became increasingly popular in the first half of the Nineties, the shifts in the cultural climate and music business practise, as the major labels and the mainstream sought to exploit ‘alternative music’, was enough to shatter Ivo’s dream to the point that he sold up in 1999 and disappeared into the New Mexico desert, cutting all ties to the music industry.

Also unlike Factory, 4AD has survived – some even claim that in the twenty-first century, the label, under new stewardship, has reclaimed its former glory. However, it is the Eighties and Nineties, the years under Ivo’s tutelage, that are the real story. This is the period that Facing the Other Way concentrates on: a time in which the word ‘4AD’ became an adjective, when 4AD was the most fanatically appreciated and collected of record labels, whose legacy casts a long shadow over contemporary music, from dream-pop, goth, post-rock and industrial to Americana, ambient, nu-gaze and chillwave. Not forgetting Pixies’ indelible influence on Nirvana, whose impact pushed alternative rock into the mainstream, after which there was no return.

There was no return for Ivo either. His non-existent profile since the end of the twentieth century means that one of the great sagas of British-label history had not been told. That is, until I went looking for him in 2010.

I’d been a 4AD fan throughout the earlier years, from Bauhaus’ early singles to The Birthday Party and Cocteau Twins, and as soon as I started writing about music, in 1983, I’d had a close working relationship with Ivo. Over the years, I’ve covered numerous 4AD artists, and been beguiled and exhilarated by the procession of sounds and names: Dif Juz, This Mortal Coil, Dead Can Dance, Throwing Muses, Pixies, The Wolfgang Press, His Name Is Alive, Lush, Red House Painters, Tarnation … But, in the wake of Ivo’s retreat, our last correspondance was in 2002 (regarding some sleevenotes I was writing about one of Ivo’s favourite 4AD signings). Arguably, a book on 4AD could have been written then, but it makes more sense now, with the label’s reputation, and myth, increasing year on year. This is a testament to a label that existed purely on its own terms, out of time and place with the rest. Facing the other way. Sometimes it’s the quiet ones you have to look out for …

chapter 1

Did I Dream You Dreamed About Me?

Creativity is a product of a diseased mind.

(Dee Rutkowski, 2011)

I have the strangest dreams every night … been going on for months. Unlike my waking life, the dreams are full of strangers that I am forced to interact with. I’m not sure whether I experience greater feelings of alienation asleep or awake.

(Ivo, by email, 2012)

Yes: I am a dreamer. For a dreamer is one who can only find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he sees the dawn before the rest of the world.

(Oscar Wilde, sometime in the late nineteenth century)

May 1985. The phone rings at Ivo’s home on a Saturday afternoon. ‘It’s David Lynch’s assistant: are you free to talk to him?’

The American film director behind the startling, surreal Eraserhead and the dramatically different, but equally affecting, biopic The Elephant Man had a new film in pre-production, titled Blue Velvet, and he’d fallen for a song that he wanted to use for the opening sequence, set at a high-school prom.

The song was a cover of Tim Buckley’s ‘Song To The Siren’, a mercurial, exquisite ballad that described, in aching and elaborate homage to the ancient Greek poet Homer’s epic The Odyssey, the inevitable damage that love causes. Buckley’s original, which the Californian singer-songwriter had written and first recorded in 1968, wasn’t at all well known, even by 1985. Between 1966 and 1974, he’d recorded a startling array of music over the course of nine albums, from folk rock to jazz to avant-garde to funky soul and AOR. It all ended with a snort of heroin at an end-of-tour party. With rock and pop culture yet to turn nostalgic, Buckley’s reputation had died with him, and punk rock’s Stalinist purge of the past had ensured that Californian singer-songwriters of all pedigrees were discourteously dismissed.

But this new cover version of ‘Song To The Siren’, by a studio-based collective named This Mortal Coil, had sprung up in a very different climate. Punk had given way to its more experimental, artful offspring, post-punk, alongside the new electronic sound, and the synthesised pop called New Romantic. ‘Song To The Siren’ had spent more than a hundred weeks in the British independent music charts during 1983 and 1984, and its fame had reached America, as David Lynch’s interest illustrated. He regards TMC’s version as his all-time favourite piece of music: ‘That song does something to me, for sure,’ he told the Guardian newspaper in 2010.

In either version, ‘Song To The Siren’ was an easy track to be infatuated with, given its sorrowful, elegiac mood, and its lyrics haunted by images of the sea and of death. The singer of This Mortal Coil’s version was Elizabeth Fraser, whose performance – supported in spirit by the guitar of her musical and romantic partner Robin Guthrie – suggested that she was the siren of The Odyssey personified, luring sailors/lovers to a watery grave.

In their daily lives, Fraser and Guthrie were known as Cocteau Twins, recording artists for the independent music label 4AD. It was 4AD’s co-founder, and singular leader, Ivo Watts-Russell, that had taken Lynch’s call that afternoon. ‘As happens,’ Ivo recalls, ‘when the film went into production, my friend Patty worked as an assistant to the producer on Blue Velvet. She’d call me, whispering, “David and Isabella [Rossellini, the female lead] are in the corner again, listening to ‘Song To The Siren’,” before shooting a scene.’

The cover version, recorded in 1983, had been Ivo’s idea. The late Tim Buckley is his all-time favourite singer, and ‘Song To The Siren’ is still his all-time favourite song. ‘Not since Billie Holiday had recorded “Strange Fruit” was a song and lyric so suited to a voice as Tim Buckley’s was to “Song To The Siren”,’ he reckons.

By 1985, the inimitable Elizabeth Fraser had become his favourite living singer. And here was Lynch, requesting not just the music for Blue Velvet but Fraser and Guthrie to mime on stage in the prom scene. However, the lawyers for Buckley’s estate demanded $20,000 for the rights, scuppering Lynch’s plans (the film’s total budget was only $3 million). The director quickly turned to composer Angelo Badalamenti, who attempted to mirror the track’s displaced, eerie mood with a new song, ‘Mysteries Of Love’, sung by the American singer Julee Cruise with her own take on haunting, ethereal projection. Starting with Blue Velvet, and most famously on his TV series Twin Peaks, Lynch fashioned a world that appeared seamless, unruffled and presentable on the surface, but scarred and disturbed underneath, foaming with a barely controllable darkness. As Twin Peaks’ FBI Special Agent Cooper declared, ‘I’m seeing something that was always hidden.’

In 2006, Ivo pointed to a similarity between label and director. ‘I feel that 4AD is like David Lynch,’ he told the Santa Fe Reporter. ‘If you say to somebody, “It’s kind of like a David Lynch movie”, you kind of know what you’re getting. It was like that in the same way for a certain period at 4AD: “It’s kind of like a 4AD record”. Actually, that probably meant it had loads of reverb.’

By this, Ivo wasn’t referring to something hidden – more that it was a brand that could be identified, where the term 4AD had become an adjective of sound. Yet in the music that the label was producing, there was the same sense of beauty as a mask for the true emotions coursing beneath. By 1985, the so-called ‘classic’ 4AD sound was all about dark dreams and hidden depths, performed by supposed fragile characters on the verge of anguish and breakdown. Take Elizabeth Fraser. After the drooling reception for her performance in ‘Song To The Siren’, she didn’t grow in confidence, but began to sing in what resembled a made-up language, or simply by enunciation, making it impossible to be understood. With a voice like hers, she didn’t need words; it was all there in her delivery, a shiver of emotion from agony to ecstasy.

March 2012. It’s been thirteen years since Ivo stood down from running 4AD and sold his 50 per cent share of the label back to his business partner Martin Mills, the head of the Beggars Banquet group of companies. But his legacy clearly lives on. The weekend edition of the Guardian has just published a feature on 4AD. ‘What is it about a record label that makes it the sort of place you want to spend time in?’ asks writer Richard Vine. ‘When it first emerged in the 1980s, 4AD felt like one of the most enigmatic worlds, the sort of label that you wanted to collect, that brought a sense of “brand loyalty” way before it occurred to anyone to talk about music in such crass terms.’

Vine cites Ivo as the reason, adding, ‘But arguably just as important to the label’s cohesion was designer Vaughan Oliver and photographer Nigel Grierson whose covers gave 4AD its distinct, haunted, painterly quality. It felt like you were peeking into a carnival full of beautiful freaks who didn’t want to be seen.’

So much of the music released on 4AD during Ivo’s era had this same creative tension, beauty masking secrets, feelings buried, persisting in anxious dreams and suppressed fear, hope and anger; lyrics that don’t explain emotion as much as cloud the issue, penned by a carnival full of beautiful freaks who didn’t want to be seen. Isn’t that what music does best, express feelings that words can’t articulate? Emotion that can’t be attached to a view or opinion, to a time or a place, is often the most timeless and precious.

People have long attached an obsessive importance to 4AD, and cited its enduring influence. On its own, This Mortal Coil’s ‘Song To The Siren’ drew extravagant praise. At the time, vocalists Annie Lennox (Eurythmics) and Simon Le Bon (Duran Duran) voted it their favourite single of the year. Today, Antony Hegarty (Antony and the Johnsons) calls it, ‘the best recording of the Eighties’. The song was to make an indelible impression. ‘For years, I was spellbound by the Julee Cruise catalogue but I didn’t know why,’ says Hegarty. ‘It was so beautiful and yet so horribly cryptic; there seemed to be something terrible lurking beneath the breathy sheen. Years later, I understood when I discovered that Lynch had originally wanted to license “Song To The Siren”.’

Irish singer Sinead O’Connor was just seventeen when her mother was killed in a car crash. ‘It was the record that got me through her death. In a country like Ireland where there was no such thing as therapy, self-expression or emotion, music was the only place you had to put anything. I played “Song To The Siren” nearly all day, every day, lying on the floor curled up in a ball, just bawling. I couldn’t understand the words much, but [Fraser’s] way of singing was the feeling I didn’t how to make. I still can’t move a muscle when I hear her sing it.’

July 2012. Ivo is driving from his New Mexico home in Lamy towards Santa Fe to an appointment with a new therapist, with Emmett sitting pillion; his black Newfoundland-Chow mix is the most eager of Ivo’s three dogs to go along for the ride, and Ivo loves his company anyway. Clouded memories of former sessions, in the inevitably elusive pursuit of happiness and to understand the nature of depression, persist as he passes through the jagged, barren landscape, the sun playing shadow games on the mounds of burrograss, the rust-coloured earth framed 360 degrees by the mountains. So much beauty and light. But inside his head, sadness and darkness.

On arrival, Ivo is pleasantly surprised when the therapist agrees Emmett can stay. ‘That’s the way to do therapy,’ Ivo reckons. ‘And Emmett loves our time together.’ But Ivo is not here to discuss Emmett, except in relation to how dogs have taught him to love unconditionally. ‘Something I have struggled to do with people,’ he says.

The black dog at his feet during the session has a special significance for Ivo. Depression is often known as ‘the black dog’, as British politician Winston Churchill famously labelled it. In 1974, towards the end of his young life, the British folk singer Nick Drake wrote ‘Black-Eyed Dog’ about the same subject. ‘A black-eyed dog he called at my door/ A black-eyed dog he called for more/ A black-eyed dog he knew my name …’

Andrew Solomon’s book The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression summarised such depression: ‘You lose the ability to trust anyone, to be touched, to grieve. Eventually, you are simply absent from yourself.’

‘Try running a record company with two offices and over a dozen members of staff with countless artists looking to you for advice, guidance and financial support in that condition,’ says Ivo.

Up in the high desert of New Mexico, 7,000 feet above sea level and 18 miles outside of the state capital Santa Fe, the community of Lamy is comfortably off the beaten track. It was once a vital railroad junction: the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) line – colloquially known as the ‘Santa Fe’ – was to stop in Santa Fe but the surrounding hills meant that Lamy was a more practical destination. But few people disembark here now. The restaurant (in what was the plush El Ortiz hotel) and tiny museum are outnumbered by the rusting, abandoned rail carts, memories of a more prestigious past. Not many people live here either: the 2010 census gave a population count of 218.

By nightfall, a hush descends; it’s the kind of place where you come to get away, or hide away, from it all. To give an idea of its isolation, America’s first atomic bomb was tested just two hours away. It’s a landscape on to which you can put your own impression, and also disappear into. ‘I’ve moved to where I feel my most comfortable,’ Ivo confesses. ‘But people just think I’m eccentric.’

It’s here, on a ridge outside of Lamy, that Ivo built his house. On the roof, you can see 360 degrees to the surrounding mountains. To the left, the Manzanos; straight ahead towards Albuquerque, the Sandias; to the right above Los Alamos, the Jemez and the Sangre de Cristo ranges that host ski season. Trails lead through the rock and scrub, but generally only dog walkers follow them; the remoteness is both impressive and comforting. In his decidedly modernist house, which stands out among New Mexico’s predominantly pueblo architecture, Ivo lives with his three dogs, his art, his music and his privacy. It’s an idyll, a hideaway, a fortress, possibly even a prison. Sometimes the only sounds are the sighs, whines and occasional barks of his dogs. The sun bakes down for much of the year. The skies are huge, the silence deafening.

Among the albums is a box set of This Mortal Coil recordings that Ivo recorded back in the day with a revolving cast of musicians, some close friends and others mere acquaintances. Some remain friends; others he hasn’t seen, talked or corresponded with for many years. No expense was spared in the mastering of this music or the packaging of the collectors CD format known as ‘Japanese paper sleeve’, though the high-end quality is more like stiff card, like it’s a book or a piece of art. These miniature reproductions of the original vinyl album artwork, only reproduced by specialist manufacturers in Japan, is the antithesis of the intangible digital MP3 that now defines music consumption. ‘I’m fascinated by the quality of what the Japanese do, and the obscurity of some of the releases they archive and document,’ Ivo says. ‘Record companies say that no one buys finished product anymore. So why not give them something of beauty?’

Shelves and drawers in Ivo’s rooms contain thousands of these limited edition box sets, which he trades as a hobby, to turn a profit if he can, ordering early and then selling on once they have sold out. After a period of not even being able to listen to music, it has again become an obsession. The music industry, or rather 4AD’s place in it, used to be an obsession as well. Not anymore. Now it’s a foggy, jumbled-up memory of highs and lows, a black dog growling at the foot of his mind.

Much contemporary music has a similar effect. Edgy, glitchy electronic music, the currency of the present technological age, ‘is just wrong for my brain,’ Ivo shrugs. He also admits he very rarely sees any live music anymore; too many people, too much fuss. The concept of the latest sound, the latest trend, the hyped-up sensation, leaves him cold. It has to be music that exists for its own sake. Music that can provide what he describes as ‘solace and sense’. For the most part, Ivo explains, ‘it doesn’t involve the intellect, but evokes an emotional response. It draws one away from analysis, from the brain constantly questioning.’

This music often comes from his past, discovered in his youth or while he was building 4AD’s catalogue, when he experienced epiphanies, love affairs, drug trips, through a cassette demo or a live show, before there was even the awareness of a black dog or what it meant to run a business. Music from the worlds of American folk and country appear to provide the most solace and sense these days. But the uncanny world of progressive rock rooted in the Sixties and Seventies, fusing the techniques of classical and avant-garde music to play havoc with tempo, texture and access, has become a recent fascination. ‘Give me originality,’ he says. ‘Give me something challenging. I listen to music now and I’m always running an inventory in my head of what it reminds me of. I mean, if you’re going to copy, to mimic, without putting an ounce of yourself into it …’

Ivo hasn’t recorded any of his own music since 1997, when he assembled a series of cover versions under the name The Hope Blister. ‘There have been a couple of times where I’ve talked about it,’ he admits. ‘I sent tapes out for people to consider, but I couldn’t go through with it. In any case, I haven’t had an original idea for years. In fact, I have no idea how I was ever that imaginative.’

Yet despite his disappearance into the desert and retirement, Ivo’s opinion clearly still stands for something. Colleen Maloney, 4AD’s head of press through the Nineties and currently at fellow south London independent Domino, heard that Ivo had fallen for Diamond Mine, a collaborative album between Scottish vocalist King Creosote and British electronic specialist Jon Hopkins that Domino had released in 2011. Ivo’s name subsequently appeared on a press advertisement beside the quote: ‘the best vocal record of the last twenty years’.

‘It’s so full of atmosphere, so sharp and so sad,’ he says, nailing the very qualities that so often elevated the music released on 4AD to such sublime heights. But, as the cliché goes, the higher you climb, the harder you can fall. Beneath the beauty, lies a deeper ocean of emotion in which to drown.