Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Ancient Wonderings: Journeys Into Prehistoric Britain»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Text © James Canton 2017

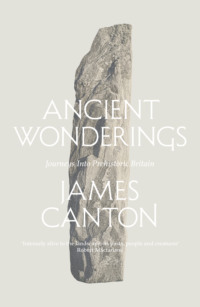

Cover photograph © Joe Gough / Shutterstock

All chapter opener photographs by the author.

Maps from ‘Ordnance Survey Maps – Six-inch

England and Wales, 1842-1952’

Excerpt from ‘At a Potato Digging’, Death of a Naturalist © Seamus Heaney, 1966, Faber & Faber Ltd.

Lyrics from ‘England’ by PJ Harvey reproduced by kind permission of Hot Head Music Ltd.

All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Prehistoric Stone Circles (3rd edn) © Aubrey Burl, 1994, Shire Publications, used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Excerpt from The Gathering Night © Margaret Elphinstone, 2009. Reprinted by permission of Canongate Books Ltd.

The author asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008175207

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008175214

Version: 2017-05-23

TO MY MOTHER

Wondering noun

rare an object of wonder, a marvel: OE

Oxford English Dictionary

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface

Stone

Doggerland

Roman Road

Mummies I

Mummies II

Peddars Way

Gold

Forging On

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

PREFACE

This book was born from a certain obsessive desire to understand the ancient world. I set out to venture across Britain seeking those prehistoric sites and phenomena that most intrigued me. Many of those travels were sentimental journeys, imaginative voyages. Inevitably, my interest in ancient Britain widened to encompass a need to know and to understand something of the ancient mindsets that created ways of living on these isles, ritual practices in these landscapes. And as I did so, my wonder took me ever deeper into time past.

I became a student of the ancient world. I learnt to step more carefully through the simplistic divisions between Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages. I learnt to recognise the magic of technological revolutions, such as that of metalworking with gold and copper brought by the Beaker people from continental Europe, and the alchemy of forging bronze from raw stone ore. Yet I also learnt to remember how even though those eras were defined by metals, stone was still very much in daily use. Flint especially remained an essential material. Agricultural revolutions burnt more slowly. The steady shift to farming – forging the first fields, sowing crops and keeping animals – that was practised by our distant ancestors took many generations to truly embed. The early agriculturalists still hunted and gathered to survive.

And then there were the Romans. Their arrival on these shores brought many changes. The arrival of the written word in Britain officially ended the era of prehistory in these isles. I knew that. But I learnt, too, that the fall of Roman feet on British soils brought no sudden shift in the ways and sensibilities of most British people.

In Ancient Wonderings, I perpetually sought to peer over the shoulders of those whose work filters our understanding of the ancient world. So I read the academic papers and books of leading archaeologists and scientists. I met them and listened to them as they spoke about their work. Their precision and patience has refined our vision of how British people lived and died and were buried and remembered in prehistoric times. I learnt by going to the places where the ancient past was still most visible and then tucking down away from the present world and digging down within, digging inside to realise what it is, what it has ever been, to be human. That process involved becoming immersed into a landscape, spending time in that world by day and by night – walking the terrain, getting to know the lie of the land: the geography, the geomorphology and the geology. To know a place you must start local – by reading its literatures and histories, listening to the voices of its peoples – steadily building an understanding and knowledge of a specific landscape, gradually unearthing a deeper topography. Then, and only really then, can you hope to venture back in time to try to see how that environment might once have looked. And only then can you begin to imagine the people and their ancient practices in that place so many years ago. It was at such times that I saw clearest – flowing through deepest time, seeking to see into the ways of past generations.

James Canton

March 2017

an illegible stone …

that is where we start.

T. S. Eliot, ‘Little Gidding’

Four Quartets

STONE

I had fallen under the spell of a stone. It was in May half-term that I found a window from teaching. To find that stone I would venture to the north-east of Scotland and so I headed north until I reached the town of Insch.

Yet I had no map. When I asked where I might find one, the two women in the chemist’s looked to each other. They could have been twins. Both had short grey hair and glasses. Their faces were round and friendly. Had I tried the DIY store? I had. What about the post office? I had tried that, too. They smiled.

‘Mmm,’ they both said.

Then one spoke.

‘What about the garden centre just down the road. They might have one.’

‘Ay, they might,’ echoed the other.

The day was grey. I walked to the edge of the town where a new housing estate was rising from the earth and then for two miles more along the B992, skipping from the tarmac of the road to the grassy bank each minute or so as a car whooshed past. A buzzard circled above. In a copse of spruce trees an incessant mewing told of young buzzard chicks. I continued to dodge the sporadic traffic and soon reached the A96 with the choice to walk north to Inverness or south, back to Aberdeen. Instead, I turned down the slip road to the Kellockbank Country Emporium. The ladies from the chemist were right. By the bars of chocolate and racks of magazines, lay just what I wanted: Ordnance Survey Explorer maps 420 and 421.

There I stood. I had travelled some five hundred miles to this windswept place in Northern Scotland, beside an A-road some twenty miles north-east of Aberdeen. I was there to see a stone – a standing stone; a stone that held a story. The only problem was that there was a locked gate between me and the stone and I didn’t have a key.

The tale of that stone had been lodged for years, tucked away. Every once in a while the knowledge would work its way to the surface of my thoughts. Then, I would find a way to tell the tale:

‘There is a stone in Scotland …’ the story would begin.

About a year ago, I had found myself in the Rare Books reading room of the British Library in London, sometime in the afternoon of a warm day in May, and rather drifting away from the research I was meant to be undertaking on an explorer of the Arabian desert. Thoughts of that stone had arrived unexpectedly in my mind. I had ordered up some books on what I remembered was called the Newton Stone.

The facts were simple: the Newton Stone was a block of granite, or rather blue gneiss, something over six feet from top to toe on which there are carved two inscriptions. One is in Ogham script – a Celtic writing system that appears as a series of scratch-like marks torn into the side of the stone. A second, more prominent, script is engraved into the face of the stone consisting of six roughly horizontal lines of writing. Each line consists of some form of exotic lettering from an ancient language: a series of swirls, curves and curlicues carved into the surface of this mass of granite. What those letters say remains a mystery. That text has yet to be deciphered.

It seemed unbelievable that there could be a piece of written script sat on British soil that no one in the world could understand. There, in that hub of all known knowledge – in London, in the British Library – I gazed incredulous that those simple lines of script before me held a message which all our centuries of collective study had been unable to fathom.

A week on, I sat at home in my study. The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland website simply stated that:

The ogam-inscribed stone (The ‘Newton Stone’) is of blue gneiss, 2.03 m x 0.5 m, and bears at the top six horizontal lines of characters and an ogam-inscription down the left angle and lower front of the stone.

No indication of mystery there. A second monument that sits alongside the Newton Stone was described as a Pictish symbol stone. The stones were in the garden of Newton House, some twenty miles north-west of Aberdeen. I rang Historic Scotland.

‘We can’t give out owner details,’ said the woman from the scheduling department.

She suggested I try calling the post office in the nearest village. I rang Old Rayne Post Office and elderly lady with a soft Scottish accent answered.

‘I’m afraid we’re not a post office any more,’ she said.

She suggested I rang the Old School House. I did. Another softly spoken voice told me to try Old Rayne Community Association.

‘They’ll know.’

I found their number and left a message on their answer machine. It wasn’t going well.

Then I received an email from Sally Foster. She was an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen who I had contacted asking for advice on the Newton Stone.

Dear James

I’m afraid that I don’t know how to contact the owners, other than to write to the occupiers of the house. Historic Scotland’s scheduling team will have full details because the monument is scheduled.

I’m dashing for a train now and will return to your question about best sources for latest thinking when I get back next week.

All the best for now.

Sally

She remained good to her word. A week later, a second email offered a list of reading and an intriguing lead:

My colleague Professor David Dumville has some new but unpublished ideas about one of the Newton stones, so I am copying him into this.

I emailed Professor Dumville immediately. Then I turned back to Newton House. Surely it was possible to find a phone number. I rang directory enquiries. A young Indian voice answered.

‘What is the name you are seeking, please?’

‘Newton House, please.’

‘Business or residential?’

‘Erm … residential.’

‘And the name?’

I hesitated; confessed I knew no more.

‘I need information to find the number,’ she stated.

She was fast, efficient: New World. I pictured her in a call centre in Bangalore. I was slow, blithering: Old World. I thanked her and hung up.

Two weeks on, there was still no reply from Professor Dumville. I emailed him again and then rang the archaeology department at Aberdeen.

‘He’ll be back next week,’ a voice informed me.

The following week I tried again. No answer. I tried a second email address. An online search had come up with a phone number for what seemed a fishery based at Newton House. The phone rang for an age. Finally, a woman answered. I said I was trying to visit the Newton Stone and wanted to speak to the owners of Newton House.

‘The big house,’ she said. ‘I don’t know the name of the people.’

She sounded nervous.

‘They’re not local,’ she added.

I asked how I might get to see the stone.

‘The house is just off the A96,’ she said. ‘Ask at the security gate for them to let you in.’

Now, I stood at the gate. Here was the moment of truth. I rang the buzzer and listened intently beneath the swoosh of cars on the main road a few feet away. There was no answer. I pressed another button on the keypad and there was a faint ringing tone like a distant telephone. It stopped.

There was a pause. A silence that lasted too long. Then nothing.

‘Hello?’ I asked.

I pressed the button again. The ringing tone started up again.

‘Hello,’ a voice said cheerfully.

‘Oh, hello,’ I said. ‘I spoke to a lady a while ago about coming to see the Newton Stone.’

There was another silence.

‘Hello?’ I said again.

A long tone rang out through the speaker. The gate shifted, squeaked rustily.

‘Come in,’ said the woman’s voice.

Magically, the gate began to slowly open before me. I stepped forward.

The gate opened on to a path, which wound down a soft incline into another world that seemed as though a kind of paradise. Birdsong rang out. A flycatcher flitted about in the still bare outer branches of a beech tree. The path led to the edge of a stream. On the far bank the skeletal remains of last year’s giant hogweed stood tall among this year’s wide young fronds – their broken frames fragile, delicate and leaning rather a-kilter. A beech hedge ran to my right. A line of broad-leafed limes ran beside the riverbank. I crossed a bridge over the river, pausing inevitably over the water before proceeding. An avenue opened before me, formed from the leaves, the branches of beech trees, which produced a distant focal point to which I slowly headed.

Newton House stood beautifully positioned before me. It was Georgian square, stately and solid beside a pea-shingle driveway. A small, rectangular sign stated ‘Newton Stones’ and pointed past the house to a smaller pathway of pale gravel, edged with sections of beech hedge that wove into woodland. Deep green rhododendron bushes bunched out into the spaces left by Douglas fir that reached high above – their bare lower trunks wonderfully sinewed. Over the ground lay a copper brush of last year’s beech leaves that soon transformed to a carpet of pink campion. The path ended.

There were two standing stones. Each stood two metres tall; each was topped with a wig of soft, green moss. Posies of yellow primrose had been planted about the stones. To the side, there was a white, metal-framed bench and a table in the form of a slab of slate resting on foot-high sections of beech trunk. For a moment I did not know quite what to do. Here before me was the Newton Stone. Here was the strange script.

I stepped closer, reached out a hand and touched the granite with my forefinger, stroked the edge of the stone as though it were some wild animal that needed greeting, gentle reassurance I was friend not foe. There was nothing of the coldness to the touch that I had anticipated.

I stepped away. The stone was the colour of cloud. In places, the surface of the stone was patched of whiter, paler shades formed by some long Latin-named lichen. The Ogham script was easily made out: a series of engraved lines, each two, three inches long; each close to horizontal and running parallel down the edge of the stone. The script appeared as a line of scars, a tribal marking that ran the length of one side of the stone. To the trained eye, these lines in the stone were far less controversial. They now made sense; they could be read. On the front of the stone was the undeciphered writing. I stared. There seemed a sinuous sense to much of the script. The letters looked as though they flowed together naturally enough and yet here before me were words that the greatest minds could not fathom, that not the wisest archaeologists or philologists, the most esteemed professors of linguistics, could make head nor tail of. There was the fylfot, the mark in the centre of the engraving: a swastika by any other name. Yet that symbol meant something so much more sinister to our modern eyes. To pre-twentieth-century eyes, the pattern was one formed by four Greek symbols: four capital Gamma signs placed together – a gammadion.

I peered at the first line of script. The initial letter looked like a lopsided C. Then an I. Then two Fs? I stopped. I had done all this before to photographs of the script. I leaned my head to the side a little. Did the script run from left to right or from right to left? I reached forward, traced each letter with my finger, then leaned my head closer, starring into the fissures of the carving.

Between the two stones, secured into the ground was a metal plaque. I brushed the bosky detritus of beech leaves and twigs away to reveal the following words:

The enigmatic carved stones are not in their original position. The symbol stone bearing a double-disc and a serpent and Z-rod is Pictish. The other stone bears Oghams – a Celtic alphabet along its side and an inscription in a different alphabet on its face. Readings of these two inscriptions are a subject of controversy.

This monument is protected as a monument of national importance under the AM Acts of 1913–53.

– Secretary of State for Scotland

On the second stone, far easier to make out, were two distinctive symbol markings: the snaking pattern of a serpent-figure, and above the double circles of a second, stranger sign.

I walked away and sat on the metal bench.

It was a beautiful setting. Mixed woodland. Beech, Douglas fir. Bluebells. Birdsong. Whitethroat and chaffinch calling. I sat and ate my lunch. There was something gloriously reassuring in that quotidian task of eating, of stepping away from the solemn presence of that standing stone a few feet before me and those illegible six lines carved across its chest. I listened to the birdsong, glanced about me at this picnic spot and then remembered: it was a folly; nothing more than an imagined site, a constructed landscape: a glade in the wood – the ancient stones framed by a beech hedge; the primula; the bench and the slate table. I laughed out loud at the ease with which a few accoutrements can create a sense of solemnity. I was sitting in a Victorian grotto.

For this was not the original site of the Newton Stone. The stone had been discovered by shepherds back in 1803 half a mile or so south on the side of a hill overlooking Shevock Burn. The stone had been brought here in 1837 and placed in the present position in 1873 as the perfect Victorian garden ornament – an ancient monument with unexplained inscriptions. Not that there weren’t learned antiquarian gentlemen already offering their theories. I had trawled the British Library. Only sixty years after the Newton Stone was unearthed there was already excited speculation. Writing in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Alexander Thomson of Banchory noted with a certain evident pride how:

It is provoking to have an inscription in our own country of unquestionable genuineness and antiquity, which up to this time, seems to have baffled all attempts to decipher it.

That was in 1863. Conjecture flourished. The eminent ‘Dr Mill of Cambridge, one of the most profound oriental scholars of the day’ saw the inscription as ‘in the old Phoenician character and language’.

I took a bite of my sandwich and looked back to those six lines of inscription then rose and returned to the stone, touched again the rough edges of that first letter, the lopsided C. The same questions swirled. Who had made these words? What did they say? Who were they carved for? Who was meant to read them?

Even to my ill-tutored eye there seemed something distinctly Oriental in the swirls and whirls of the lettering. The Phoenician theory was one that had held for a good while. L. A. Waddell was a Victorian antiquarian and linguist whose elaborately entitled work The Phoenician origin of Britons, Scots and Anglo-Saxons: Discovered by Phoenician and Sumerian Inscriptions in Britain, by pre-Roman Briton Coins and a mass of new History had first been published in 1924. Waddell claimed not only to have deciphered and translated the Newton Stone script – which he dated to 400 BC – but saw the monument as evidence of Phoenician colonists who were the ancestors of the ancient Britons.

I rather liked the notion of Phoenicians reaching the north of Scotland on one of their expeditionary trading missions and their decision to stay, to settle here. It was a fanciful one, of course. I mused a moment on Waddell’s theory, sat there beside the stone, and imagined a young Phoenician traveller who falls in love with a local lass. He will stay, he declares. He cannot leave. Time passes. He prospers, grows old. He has spent a lifetime here. He prepares for his final journey, the one to the undiscovered country. He commands a stonemason to carve a message into one of the vast standing stones. He remembers pieces, fragments of his native language.

It was time I moved on. I packed up the picnic and placed my hand on the stone. It was an odd gesture, I thought later, and yet I did so automatically all the same, as though touching the shoulder of a friend in farewell. The pale gravel pathway continued on through gladed woodland. The map had shown a track running down from the grounds of Newton House, from what were referred to as ‘Sculptured Stones’, away south through open fields to further woodland, running directly to the original site of the stone. Strangely, the map also indicated the track would pass a mausoleum within the grounds.

It was while on the trail of the Newton Stone, tucked away in the recesses of the British Library, that I had discovered John Buchan’s The Watcher by the Threshold. 1 The work was a collection of stories first published in 1902 and all set in Scotland. In a dedication to his friend Stair Agnew Gillon, Buchan stated:

It is of the back-world of Scotland that I write, the land behind the mist and over the seven bens, a place hard of access for the foot-passenger but easy for the maker of stories. Meantime, to you, who have chosen the better part, I wish many bright days by hill and loch in the summers to come.

J. B.

R.M.S. Briton, at sea

September 1901

It was the first of the stories – ‘No-Man’s Land’ – that most intrigued. Buchan’s tale tells the sad fate of a young Oxford academic, an archaeologist called Mr Graves, who is holidaying in his Scottish homeland. Graves is entranced by the Picts:

They had troubled me in all my studies, a sort of blank wall to put an end to speculation. We knew nothing of them save certain strange names which men called Pictish, the names of those hills in front of me – the Muneraw, the Yirnie, the Calmarton. They were the corpus vile for learned experiment; but heaven alone knew what dark abyss of savagery once yawned in the midst of this desert.

Graves tells of his own journey into the heart of this landscape. He meets an old shepherd and his wife who talk of lost lambs, of sheep found dead with a hole in their throats. Graves laughs at mention of the Brownie – those mythical, half-forgotten beings; shrunken, ancient men who were said to still live in the wildest spaces of the moors. He heads out for a place called the Scarts of the Muneraw:

… in the hollow trough of mist before me, where things could still be half discerned, there appeared a figure. It was little and squat and dark; naked, apparently, but so rough with hair that it wore the appearance of a skin-covered being.

Graves has met the Brownie – those remnants of the still-surviving Picts. He flees in terror but is chased, bundled to the ground and knocked unconscious.

I had paused my reading to check up on the Picts. They were a people of north and eastern Scotland dating from pre-Roman times until the eleventh century or so when they merged with the Gaels. These were Buchan’s Brownies. Then I had rung Professor Dumville’s phone number again.

‘The number you have dialled has not been recognised. Please check and try again.’

I had been expecting a Scottish voice to answer. Instead the recording was oddly clipped – the Standard English of an imperial English voice from a century ago – in fact, a voice rather well suited to a figure like Buchan’s Oxford academic Mr Graves. Professor Dumville seemed to have vanished from all possible communication. I rang the main university switchboard. The operator tried the number. The same imperial English voice answered.

‘Yeah, that’s very strange,’ she agreed in a Scottish tone. ‘I’ll report it to the engineers.’

In the meantime, she put me through to the Department of Archaeology’s general office. I left another message then returned to ‘No-Man’s Land’.

Graves wakes to find himself ‘in a great dark place with a glow of dull firelight in the middle’. He gathers his courage and speaks in dimly recalled Gaelic. A tribal elder from the back of the cave stumbles forward: ‘He was like some foul grey badger, his red eyes sightless, and his hands trembling on a stump of bog oak.’ The old man speaks. Graves is spellbound:

For a little an insatiable curiosity, the ardour of the scholar, prevailed. I forgot the horror of the place, and thought only of the fact that here before me was the greatest find that scholarship had ever made.

Graves hears of the survival of the Picts – of girls stolen from the lowlands, of ‘bestial murders in lonely cottages’. Then he escapes. He flies from the hill cavern and from Scotland, back to the cloisters of St Chad’s, Oxford where he burns all books, all references to the moorlands. But, of course, Graves is tortured by the knowledge he now holds. Reluctantly, he returns to the Muneraw and finds himself once more in that hidden hillside where now a young local woman is being prepared for sacrifice. Graves fires on these strange ancient relics of men and flees with their captive. A final struggle on the edge of a ravine sees one of the remaining Picts fall ‘headlong into the impenetrable darkness’. Graves is badly injured; dazed, but still alive.

There the narrative breaks. The last chapter of ‘No-Man’s Land’ is told by an unnamed editor. Graves’ words were written before he died of heart failure. An obituary notice in The Times is quoted which remembers the great potential Graves showed as an archaeologist, though tempered with the caveat that:

He was led into fantastic speculations; and when he found himself unable to convince his colleagues, he gradually retired into himself, and lived practically a hermit’s life till his death. His career, thus broken short, is a sad instance of the fascination which the recondite and the quack can exercise even over men of approved ability.

I stepped away from the stones yet was loathe to leave. In the woodland, the extraordinary song of a tree pipit reverberated bold and fluid as a Highland stream, rattling and ranting over the low cover of creeping ivy and floods of pink campion.

The track left the trees and followed the line of the River Kellock to a sheep field that had been fenced off. I stepped gingerly over, scattering sheep up the hillside towards the incongruous and faintly unnerving sounds of traffic coming from the nearby A96. I held close to the Kellock. A farm track carved by tractor wheels ran beside the riverbank, which was smothered with the triffid-like leaves of hogweed. I glanced at the map where the track marks ran straight to the original site of the stone. Before me was more barbed wire. Beyond, through a copse of trees, I could make out a building of some sort. I followed the farm track, down to the flood plain of the river. The stones had been described as being in a plantation near the Shevock toll-bar. This was the raised triangle of land I now stood before. I looked about. Three crows flew by. Sheep stared. I tried to picture the stones earthfast on the embankment above. South ran the valley of the River Shevock; north rose the dark Hill of Rothmaise. This was no place to linger. I felt it. Something was hurrying me away. I was standing on someone else’s land. The enclosed copse with the smallholding felt full of shadows. I looked back to the map and traced the snaking, red line of the A96. I had circled in pencil the stone circle on Candle Hill past Old Rayne. I turned back to the land. Barbed-wire fencing surrounded. I walked on heedless, away from the copse until the Shevock blocked my path, then lurched ungainly over a section of fencing and clambered up towards the road.

Past Pitmachie, I crossed the bridge over the Shevock and wove into the village of Old Rayne, up past the market cross where a line of schoolchildren snaked downhill as I went up, climbing the inclines to Candle Hill where a starling greeted my arrival from the rooftop of an abandoned farm shed. I sat on one of the fallen outliers of the stone circle. The clouds of earlier were clearing. A breeze blew. There was blue sky to the north over Gartly Moor and the Hill of Foudland. I gazed back and could make out that triangular embankment of raised land, the original site of the stone.

The belief that the Newton Stone had been carved in that strange script as some form of memorial was one that had held strong since the modern unearthing at the start of the nineteenth century. There was a logic in seeing a funereal nature to the engraving; that the stone had been a gravestone and the words an epitaph. Certainly, that was what I had assumed. In a paper published in 1882, the Earl of Southesk – the writer offered no other name – had noted that when ‘trenching’ of the Shevock area had taken place around 1,837 human bones had been found ‘a few yards’ from the original site of the Newton Stone. On the sleeper train up to Aberdeen, with notions of the Newton Stone and its enigmatic engraving playing along to the motion of the tracks, I had tucked down to sleep and begun to imagine that I was indeed one of the dead and was in fact lying in a sarcophagus of some sort, starting on that journey to the next world, the narrow bunk bed and the low roof helping to frame my fanciful thoughts. I placed my most valuable possessions about me, in the soft edges of the upper bunk, as though they were some form of modern grave goods – items that I would need in my next life: iPod, mobile phone, torch, glasses, and wallet.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.