Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Full Steam Ahead: How the Railways Made Britain»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2016

© Lion Television Limited, 2016

Photographs © individual copyright holders

Design and layout © HarperCollins Publishers 2016

By arrangement with the BBC.

The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence.

BBC logo © BBC 1996

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Full Steam Ahead was produced by Lion Television (an All3 Media company) for the BBC in partnership with the Open University.

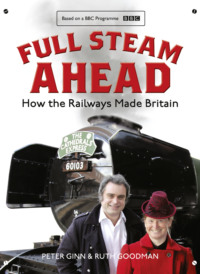

Cover photograph © Stuart Elliot/Lion TV with permission from the National Railway Museum.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008194314

eBook Edition © July 2016 ISBN: 9780008194321

Version: 2016-07-26

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all the men, women and children who have given life, limb or time to the creation and preservation of Britain’s railways.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter One: INDUSTRY

Chapter Two: MOVING PEOPLE

Chapter Three: AGRICULTURE

Chapter Four: COMMUNICATION

Chapter Five: TRADE

Chapter Six: LEISURE

Index

Picture Credits

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

About the Publisher

The Victorian era was a period of immense change in Britain. It saw both the flowering and culmination of the agricultural and industrial revolutions, huge social reforms and massive technological advancements. The greatest of these was almost certainly the steam railway.

The railways changed the world. This is a bold statement, but it is unquestionably true. How scientific advancement comes about and the impact it has upon society is a complex issue. We often view our history in segments that are allocated according to the lifespans of rulers – for example, ‘the Victorian era’. However, the simple fact is that we are all part of a human race that ebbs and flows as it develops and changes over an indeterminate period of time – and this process is impossible to comprehend completely as it is happening. To divide history up into segments is one step towards trying to understand it. The timeframe of the birth of the steam railways, and their subsequent development and decline, is akin to the lifespan of a human being. Therefore, the age of the steam railways is a good lens through which we can study the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Unlike most rulers whom periods of time are named after, the steam railways dramatically changed our lives and the lives of our ancestors. The world was already becoming a smaller place. To paraphrase Roald Dahl, at the time of the advent of the railways, there were only a couple of pages in the atlas left to fill in. The idea of using steam power was not new, but the creation of an effective engine that could convert energy into work was most certainly a massive innovation. The first steam engines had a major impact. They were big and heavy, but within reason they could be situated anywhere. Once in place, the steam engines provided power, thus reducing the need for labour. They found their calling in some factories, in agriculture and in mining.

Furthermore, railways were not a new concept. Throughout history, there has been archaeological evidence that indicates the use of trackways in various parts of the world. Also, the concept of wheels running on steel rails is not too dissimilar to that of boats travelling on canal water, when it is broken down to a basic mathematical level. Both methods of transportation reduce friction, allowing heavier loads to be pulled using less force. Just like the steam engines that pumped water out of mines, horse-drawn railways moved material from the very same mines down to the ports. However, it was the successful marriage of these two concepts that changed the world.

The Victorians were unstoppable innovators, and their era was marked by massive industrial and technological development. This is the giant waterwheel at Laxey, Isle of Man, constructed by the Casement firm in 1854.

The presenters of Full Steam Ahead, historians Peter Ginn, Ruth Goodman and Alex Langlands, about to board the preserved steam engine, 60103 The Cathedrals Express.

FULL STEAM AHEAD

In the nineteenth century, the term ‘locomotive engine’ was first used to distinguish a steam-powered engine that could move forwards and backwards from a completely static engine that merely provided power. Once the idea of a moving engine was proven to be viable, it led to a frantic creation of railways that spread across the globe. The nineteenth century saw an exponential amount of scientific development and social change, and so much of that is tied into the development of the network of railways, in both Britain and around the world.

This book has been produced to accompany the BBC 2 series Full Steam Ahead. In order to help ourselves examine the many and varied everyday stories from the steam railways, we divided the television programmes loosely into six themes: industry; moving people; agriculture; communication; trade; and leisure. Obviously, there is a huge overlap between each of these themes and sometimes the distinction between the programmes leaned more towards a geographical or a chronological separation. However, the themes are a good way for us to be able to focus the television programmes. It was also through dividing the various stories between each of these loose themes that we realized just how much the railways impacted on every aspect of life.

Many of the projects we have undertaken before, both for the purposes of television and for research, and have been concerned with rediscovering lost skills. Having now embarked upon a project studying the railways, we have had the chance to contextualize our work by studying the industrial side of a society that was experiencing a growing population shift from the agricultural to the urban.

Why did railways have such an impact on society? It is chiefly because of the speed of travel that they facilitated and the extent of the network that was built to support them. Not a single British railway mainline track was constructed in the twentieth century: all were created in the nineteenth century. The railways linked tiny villages and even hamlets with towns, cities and ports. Suddenly, people could pay some money for a ticket, get on a train and be in the centre of a growing metropolis or in the middle of nowhere within a matter of hours or minutes. The roads had previously linked settlements together, but they were very poorly constructed and journey times were long. Relatively speaking, the railways allowed people to travel great distances in no time at all.

“ONCE THE IDEA OF A MOVING ENGINE WAS PROVEN TO BE VIABLE, IT LED TO A FRANTIC CREATION OF RAILWAYS ACROSS THE GLOBE.”

Presenter Peter Ginn pictured together with the Strathspey whisky distillery team, in front of the preserved railway that serves the factory.

Wylam Dilly, sister locomotive of Puffing Billy, photographed in 1862. Suddenly, what had once been only static engines could move, opening up a whole new era in the transportation of both goods and people.

“THE WAY THAT VICTORIAN PEOPLE VIEWED SOCIETY AND INTERACTED WITH ONE ANOTHER CHANGED FOR GOOD.”

Much of nineteenth century industry involved the movement of great weight and bulk – huge amounts of what is collectively known as ‘tonnage’. Lumps of iron, piles of coal, gallons of beer for the workers – they all needed transporting. For the first time ever, the railways enabled heavy materials to be moved quickly and on time. Yet, as much as industry built the railways, the railways built industry. This speed of movement also allowed ideas to travel quickly. Vast quantities of newspapers thundered up and down the country on trains as circulations increased and the telegraph network that accompanied the railways permitted information to be relayed at the speed of light. Something could happen in the Highlands of Scotland, be reported to a newspaper office in London, be printed and then be on sale in a shop in Aviemore, back in the Highlands, before the dust had settled. Suddenly, the whole world was moving at a pace not seen before in human history, and communications would never be the same again.

Consequently, the world became a much smaller place. Developments in the railways in Britain occurred alongside economic, social and political changes and advancements being made in America, Europe and beyond. Lessons were learned and thoughts were shared. A product designed in a small village in Wales could have a major influence on peoples’ lives in northern Russia. As much as railways were pioneered in Britain, their evolution was a worldwide affair.

The way that Victorian people viewed society and interacted with one another changed for good. For a start, if it was ten o’clock in Swansea, then for the first time ever it was also ten o’clock in Newcastle. The introduction of what was known as ‘railway time’ saw to that (see here). The island became unified in a way that it had never been before. The speed of the new transport system also meant that no longer did people have to seek employment close to where they lived. Trains allowed people to commute to work, for the first time ever. The railways also removed the social and economic constraint of having to grow enough food to support a local community. Food imports were nothing new, but until the railways were built, food that spoiled easily – such as fish, milk or vegetables – had to be sourced close to where a population lived. The railways could import these commodities quickly, in some instances faster than it is possible to do so today using an existing courier network. This allowed the countryside to concentrate on the cultivation of perishables and the cities no longer needed to be in easy reach of green fields or had to keep milking cows in an urban environment. Suddenly, the cities could expand and focus on industry instead of agricultural concerns.

Presenters Peter Ginn and Alex Langlands giving a preserved steam engine a thorough cleaning in the time-honoured – and very necessary – fashion.

Trains cut through impoverished urban environments and gave many their first taste of how the other half lived. This new, widespread awareness of the proliferation of urban slums in Victorian Britain prompted much of the social reform that began in the nineteenth century. Trains also offered travel that was affordable to all but the very poorest, altering the way that the economic classes interacted and changing the natural barriers in Victorian British society.

As a general rule, historians find it difficult to isolate events in history and argue their impact upon society, when they are so well woven into the continuous tapestry of life. However, it is perhaps because of how embedded steam railways are in the development of the modern world that allows us to say they changed the world. Our lives right now are a direct result of the innovators, visionaries, designers, workers and daily users that created and advanced the steam railways. Had that development not have happened as it did, we would be living in a very different society today. Arguably, many of the problems we face today are an indirect consequence of economic, social and political developments in the nineteenth century, but so too are the solutions. Thanks to the introduction of the railways, we may have lost some sense of British regionality, but we can offset that against a sense of British unity.

“TRAINS CUT THROUGH IMPOVERISHED URBAN ENVIRONMENTS AND GAVE MANY THEIR FIRST TASTE OF HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVED.”

It is impossible to contain the entire story of the railways in only one volume. There are countless little anecdotes and backstories that deserve coverage but which would fill many hundreds of pages beyond those contained in this book. For example, did you know that when the Flying Scotsman was running low on supplies or had an onboard emergency, the crew would write a note, insert it into a potato and throw it at a signal box as the train passed by? They did this because, at the time, there was no other way to contact or alert the outside world. However, once the signalman had received the flying potato with its important missive, he could telegraph ahead to ensure that the speeding train’s problem could be addressed further down the line.

The railways gave many people an insight into the horror of urban slum dwellings for the first time. This is Wentworth Street, Whitechapel, in Victorian London, as depicted in an engraving by Gustave Doré, 1872.

Peter, Alex and Ruth welcome you to this book accompanying their television series and hope you will enjoy reading about the establishment of Britain’s steam railways.

Stories like this one and the many nuances of historic railway travel are infinite and most of them lost in time. However, this book is our attempt to go a little deeper than we can on a television screen, to examine a little more closely the detailed history of the railways. To the best of our knowledge the contents are accurate, but we apologise for any mistakes. We hope you enjoy reading about how the railways of Britain changed our lives forever.

It was heavy industry that spawned the railways and the railways that were then to drive the expansion of heavy industry. The two went hand-in-hand, mutually supportive and entirely co-dependent throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Ffestiniog railway in the heart of Wales is the world’s oldest surviving narrow gauge railway, dating back to 1832. It is thirteen and a half miles long and runs between Ffestiniog and Porthmadog, through some of the most dramatic and beautiful of Britain’s countryside. The railway was built in order to transport slate from the quarry to the docks, bypassing a long overland route by packhorse, cart and river boat. Small manageable wagons could thence be loaded right at the quarry mouth and moved smoothly, without any slate-damaging jolts and knocks down to the harbour quayside, within a couple of hours. It was a vast improvement over the old system. Even a narrow gauge wagon could carry a much bigger load than a packhorse, and it cut out entirely the need to then unload the slate from those horses and reload it into small, flat-bottomed riverboats. These then had to be sailed downstream with the tide along the somewhat energetic but shallow river Dwryrd, only to need unloading again before the slate was transferred to the sea-going vessels. Just one year earlier, the tax upon the coastal transport of slate had been lifted – and the overland routes and imports had been significantly unburdened by this financial control – so the moment was ripe for the Welsh slate quarries to increase their production and share of the market. The owners of the Ffestiniog quarry, Samuel Holland and Henry Archer – the first a quarryman and the latter a Dublin businessman – decided that this was the moment to invest. What they decided to construct was a railway line of a type that they were familiar with, a tried and tested technology that had enhanced and expanded the businesses of several of their quarrying neighbours. Because, despite its status as the oldest surviving narrow gauge line, the Ffestiniog railway was by no means the first, even in the mountains of Wales, and it was entirely lacking in locomotives.

THE EARLIEST RAILWAYS

Railways existed long before steam locomotives and even before static steam engines. Indeed, the first recorded mention of a railed way for wagons in Britain can be dated to the very start of the seventeenth century – in 1603, the same year that Elizabeth I died. Over the next two centuries, many remote sites from Northumberland to Snowdonia constructed flat or gently sloping track-ways with wooden guide rails, so that heavy loads could be moved easily around in a controlled manner using muscle power – either that of humans or horses. Mines and quarries were the major users of this transport system, as they were the businesses that had the heaviest and bulkiest of materials to move in volume. It was the weight of the loads that made a railed way so preferable to an open roadway. Rails provided a way of spreading the wagon’s heavy load across the ground, rather than it being concentrated upon the couple of inches where the wheel met the road surface. Where road vehicles quickly churned up the mud and became stuck, railed wagons glided across. Rails also helped control the direction in which a wagon moved and kept it within a series of set locations. Mines and quarries were busy places that often featured many narrow passageways and restricted spaces, so this element of control and organization was extremely valuable.

Still in operation to this day, the Ffestiniog railway’s origins lie in Welsh slate mining during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Presenters Peter Ginn, Alex Langlands and Ruth Goodman on one of the station platforms on the Ffestiniog railway.

As time went on, mine and quarry owners refined the systems that they used – improving wagon shapes, finding ways of making stable, well-drained trackways and, from around 1760, adding iron strips to the top of their wooden rails in order to prevent excessive wear. Fully iron rails arrived a generation later, cast in three- or four-foot long sections. It was this well-developed, muscle-powered railway that appeared upon the hills of Snowdonia in 1798, when the Ffestiniog’s neighbour, the Penrhyn quarry, built its railway. Railways then were the servants of industry; they were shaped by its needs and they existed in places wherever industry needed them – often far from centres of population. However, at this time the railways were still very much a junior partner in the complex networks of waterways, sea routes and roads that joined up the trade of the British Isles.

SLATE

When the Ffestiniog railway was first built, it was constructed so that the two rails were 23½ inches apart (this distance between the rails is what is referred to by the word ‘gauge’). Such a restricted gauge was chosen partly because a narrow gauge requires a much smaller path to be cut through tunnels and cuttings. It also uses less expensive, narrow bridges and fewer materials altogether. However, the narrow 23½-inch gauge was also chosen because this was the gauge of the rails that were already in use underground within the quarry.

The narrow gauge used for the Ffestiniog railway was inexpensive and designed to enable access to the darkest corners of mines and other inaccessible areas.

Some slate is quarried in an open-cast fashion, but the quarry at Ffestiniog is more akin to a conventional mine. The slate here is of a very high quality, allowing it to be split by hand into remarkably thin, consistent and structurally sound layers. In 1935, one Ffestiniog worker described how a single piece, only one inch thick, could be split into 26 layers, so that each slate would be a little less than a millimetre thick. Such thin layers were also fairly elastic and, crucially, they did not absorb water. This meant that slate from this deposit could be used to make superb roof tiles. They were very light due to their thinness, were able to cope with the slight warping of roof timbers and they did not become heavier when it rained. This meant that a roof covered in Welsh slate could be constructed from much lighter, thinner timbers than that of any other available material. The Ffestiniog slate shed water beautifully, too, meaning that roofs could be built with a far less steep pitch to them. Imagine the impact that all this had upon house building at the time. Indeed, you can see it around you to this day. The roofs of old cottages that were built to take thatch have a very steep pitch (around 70 per cent), even if the thatch itself is long gone. Think instead of the rows and rows of Victorian houses – the roofs are much shallower, rarely pitched at no more than a 45-degree angle, 30 degrees being much more common. The costs of building such a slate-roofed home with its smaller surface area and smaller, lighter timbers was substantially less than that of building a thatched home.

Ffestiniog slate was of the highest quality. It could be easily split and fashioned, was ideal for lightweight, supremely waterproof roofs and was also cheaper than most competing materials.

Due to an expanding population, the demand for cheap, yet properly watertight houses was high. The townscapes of Britain were utterly transformed as the slate industry blossomed. And it grew very largely because of the improved transport that the railways offered. While the output of the quarries had to be carried away by packhorse and small riverboat, there was little incentive to increase production – the quarry owners would simply not have been able to shift much more material. However, even without locomotive power, the railway could move exponentially more material, as well as moving it more quickly. Moreover, this new method of transport, whilst requiring an initially large capital outlay, was much cheaper to run. In many ways, the slate industry is simultaneously an example of an industry with a latent market waiting to be filled as well as one bursting with resources ready to be exploited. Transport was the bottleneck. The railway opened up the flow, and money and people poured in.

“THE SLATE HERE IS OF A VERY HIGH QUALITY, ALLOWING IT TO BE SPLIT BY HAND INTO THIN, CONSISTENT AND SOUND LAYERS.”

Victorian quarrymen were a hardy breed, who largely fashioned slate by hand, before the mechanistic advances of the mid- to late nineteenth century.

In 1808, the entire parish of Ffestiniog was home to 732 people; by 1880, that figure had risen to 11,274.

During the nineteenth century, the only real competition for slate as a roofing material was tiles. However, in the 1830s these were still heavier than slate and also expensively hand produced. Of course, slate also required a good deal of handwork, from extraction to shaping – but it was still cheaper to produce. The quarrymen worked in small gangs of between four and eight men and their wages were determined by the finished output of the gang. About half the members of the gang would be ‘rock men’, who cut the slate out of the ground. The others would be equally divided between ‘splitters’ and ‘dressers’, who shaped the rock into slates. Independently of these gangs, ‘bad rock men’ were employed to remove other rock that was impeding progress and ‘rubbish men’ to remove the waste rock. By 1860, sawing, planing and dressing machines assisted in dividing up the large rough blocks into more manageable pieces for the splitters to work with, and helped trim the edges into regular, standardized rectangles. Rather than reducing the amount of work as such, mechanization allowed for faster processing, which in turn brought costs and prices down. All these factors made slate even more competitive as a product compared with its main alternative, tile.

The Ffestiniog railway line is a remarkable feat of engineering. With no motive power, the loaded wagons were intended simply to run down to the quay under the force of gravity. That meant that the gradient of the line had to be a steady one-in-eighty. If the railway became steeper, the trucks might speed up and run themselves off the rails at the bends; if the line flattened out, there was the danger of the wagons slowing to a standstill. Only the very last portion of the line was level, where the momentum of the loaded wagons was enough to allow them to run on for a distance before gently stopping just before the quayside. The surveying and construction skills involved in the building of the line can still be seen and appreciated today, as the line snakes its way around the hillside over embankments and through cuttings, following the contours of the landscape. Such skills had been honed in building the canals, and by the mid-nineteenth century they were the stock in trade of a large body of professional men and skilled labourers.

These days the Ffestiniog railway no longer transports slate – only passengers. However, its proud heritage lives on.

Historian Ruth Goodman aboard the Ffestiniog railway steam train Prince.

SLATE MINING

Widely known as ‘blue gold’, the slate extracted from Welsh mines has been used to cover roofs across the globe. Welsh slate mining was an industry that expanded with the railways. It began with simple horse-drawn railways that took the slate from the mine to the ports and ended with an extensive rail network that could move vast quantities of heavy loads across the entire country.

Prior to descending into the mine, we looked at the exposed stratigraphy of the rocks around us. The band of slate was quite clear and went down into the ground at a 35-degree angle. We entered the mine, went down the trackway that would have once been used to haul up the slate, and found ourselves in a different world. The mine we were in was the second largest slate mine in Wales (the biggest was just across the road). Branching off a central circular passage were a number of caverns from which the slate was extracted. I was asked by our television sound engineer, ‘why are you whispering?, and the only answer I could give was that the mine reminded me of a cathedral.

Families which lived near the Welsh slate mines often worked together in gangs and were paid according to the amount of usable slate that they produced. Once you were assigned a plot, as a miner you had to see it through until the slate was exhausted. This could easily take up to 30 years. As a rule of thumb, of all the material extracted from the ground, only ten per cent was usable as roof tiles. The rest was cast onto giant heaps adjacent to the railway near the entrance of the mine. This has completely changed the surrounding landscape, effectively creating new hills.

Slate is a sedimentary rock formed in layers that are easily visible to the naked eye. To mine it, holes were drilled by hand, perpendicular to the grain. On a new face of slate, before a platform was created upon which the miners could work, the first holes had to be drilled. To do this the miners used a chain wrapped around one of their legs, which supported their weight.

Slate is a relatively soft rock, so the drill that makes a hole which can be filled with powder and a fuse to blast a new face is simply an iron rod with a bulbous section that is heavy near to one end. The short end of the rod is used to start the hole and the long end to finish it. The drill is simply moved up and down by hand and the weight pulverizes the rock below to dust.

We were in the mine with electric lights and modern access routes. When the mine was fully operational in the nineteenth century, each cavern may have been lit by just one candle. The miners covered their own expenses, so burning lots of candles would impact on profit. The work was repetitive, often dangerous – especially when blasting – and the men spent much of their time chained to rocks in the half-light. In some instances, it is easy to imagine these conditions breaking the spirits of the miners, but in Wales it was quite the opposite. Poetry, song and political ideology were all penned in the mines. Lunch was taken in a caban (Welsh for cabin) built out of discarded slate in the mine area that the men were working. It was here that many discussions took place – and they were often minuted, so some records of their contents still survive to this day. Competitions with miners from other caverns also took place, often based on song or poetry.

However, it was above on the surface where the real competition was arguably happening. The slate taken up there had to be cut down to size in order to make the roof tiles. Tiles ranged in sizes and had names such as ‘king’ (largest), ‘empress’, ‘princess’ or ‘lady’, according to their dimensions. The skill of the cutter and the speed at which he worked would directly impact upon the usable product produced. The rock had to be sawn, split and trimmed – and slate dust is not kind to the lungs....

STEAM

However, we must not forget steam. That, too, has a long and convoluted history. Claims that such and such was ‘the man who invented the steam engine’ tend to obscure the fact that all great people stand upon the shoulders of giants. Look closer, and what you see is a long journey of ideas, experiments, refinements and improvements, with the baton of progress moving from one hand to another, and advancements often dependent on other tangential developments. Amongst all the great visionaries and engineers involved in the story of steam engines, one of the greatest was James Watt. Using huge skill, he applied new scientific thinking from the academic world and combined it with what he discovered by analyzing the working model of another man’s engine. This statement, of course, does not take anything away from Watt’s genius or his astonishingly hard work. But steam engines did not simply pop into existence one night after somebody watched a kettle boiling…

Darmowy fragment się skończył.