Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Nice Big American Baby»

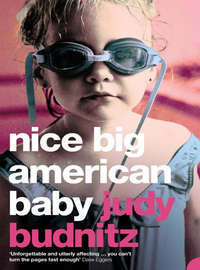

nice big american baby

judy budnitz

dedication

for amanda davis

contents

cover

title page

dedication

where we come from

flush

nadia

visitors

saving face

miracle

sales

elephant and boy

immersion

the kindest cut

preparedness

motherland

acknowledgments

about the author

praise

by the same author

copyright

about the publisher

where we come from

1. before

There was a woman who had seven sons and was happy. Then she had a daughter.

She loved her sons with a furious devotion. But she did not want the daughter, even before she knew it was a daughter. She could feel the baby sitting low in her belly and did not want it.

Another burden on my back, the woman thought, another mouth to feed.

From the moment the girl was born she was frail and sickly; she greeted the world with a sneeze. The mother heard the sneeze and felt a heaviness descend upon her heart. Even with the best coddling and foreign medicine, the girl would probably die within the month. Three years at the most. A waste. It would be better, she thought, if the girl died now and got it over with. There were many ways a baby could die. Infant death was common in that part of the world; no one would notice one baby more or less.

Then she looked at the tiny wrinkled face and felt ashamed. She resolved to love her daughter as she did her sons.

She named the girl Precious, to remind herself.

She made a promise to her daughter, but her seven sons were a delight and a distraction and if she did not break that promise she did bend it to its limits, like a young tree in a windstorm. Precious learned to make no demands on her mother. She took the food from the bottom of the bowl at meals and kept her feet clean so she would not leave footprints behind her.

The woman was happy. Her sons grew tall. People told her how lucky she was: eight children, all of them still living.

But I have seven children, she would say. And then: Oh. Yes.

One year the rains came doubly hard, the roads became rivers of mud, and the fruit rotted on the vine. The next year the rains did not come at all. Surely, people said, the third year will be a good year. But they were wrong.

It had never happened before—two years without rain. Even those people who considered themselves modern began to pray again and to hang charms at their doors.

The underground stream that fed the electric pump in the village dried up. The woman’s sons went searching for water. They were tall and thin and knew how to travel in the heat of day. They ran and rested, ran and rested. Each time they paused they arranged themselves in a descending line so that all but the oldest could rest in a brother’s shadow.

They had taken buckets and jars to carry water back to their mother. And to Precious. Precious: always remembered, but always as an afterthought.

They found a wire fence. The top of the fence was lined with prickly wire like a thornbush. They tore their hands on it, climbing over. Far in the distance they could see a dark smudge bleeding into the sky. They ran closer. It was the largest building they had ever seen, massive and gray and faceless, with three tall chimneys like fingers pointing to the sky. The black smoke that poured from them was like nothing they had ever seen before. It hung in the sky without dissipating, it was dense and heavy, like rain clouds about to burst.

The oldest said it was a rain factory. He said he remembered hearing people talk about it. He was sure.

Yes, said another, I heard that too. It’s true.

Beyond the building they saw a pool, almost a lake. It was perfectly shaped and perfectly still, and the water was the strangest color they had ever seen—bright, bright blue and iridescent, with pearly rainbows on its surface. They agreed that the color must mean it was very pure.

The first one to taste the water became very sick. His brothers watched him twisting and retching, his arms folded in on themselves like wings. A thick white gravy came out of his mouth and nose. They heard a roaring in the stillness and looked up to see two trucks speeding toward them trailing clouds of dust. They lifted their brother and ran.

They knew their brother could not climb the fence, so they hid among the rocks where they knew the trucks could not follow, and they waited for dark. They dug beneath the fence with their hands. It took them most of the night. They knotted their shirts into a sling and headed home, carrying their brother between them.

The woman was waiting on her doorstep for her sons to return. In the red light of dawn she saw their silhouettes approaching. She counted only six bobbing heads and began to keen in her throat.

Her son did not die. Eventually his hands uncoiled and he was able to walk again. But he was not the same as he was before. His face had hardened into a new expression that made him look like a suspicious stranger.

She knew that was not the end of it. The poisoned water was the beginning, a portent of what was to come. She was not surprised when, soon after, her sons began to disappear one by one.

The rains still did not fall. Everyone was hungry. The earth was cracked and barren. There was no work to be done, and anger and discontent began to ferment in the hearts of the people. Some complained against the government, though many had never seen the slightest evidence of any government and did not believe it existed. There was talk of electing leaders, building an army, an army for the people. The woman listened but did not understand how an army could bring the rains.

The woman’s eldest son came to her and said he was going to become a soldier.

But you’re just a child, she said.

The army has a whole division just for children, he said. I’m already too old for it. I will have to join the men.

She saw his thin chest surge with pride as he said this, and her heart ached.

So he left and she knew she would not see him again. Soon another son left to join his brother. It was the one who had drunk the tainted water; he waved as he walked up the dusty road and she could see he was trying to smile for her, but his facial muscles were frozen in a sneer.

One of the younger boys announced that he was going to join the children’s army. She forbade it. He ran away in the night.

She heard rumors of fighting, the people’s army fighting the government’s, factions of the people’s army fighting each other. There was an outbreak of fever in the village and many people died, including her youngest son.

So she had three sons left. Then two more went off to fight. They went together; that, at least, was a comfort.

Don’t become a soldier, she told her last remaining son.

I don’t want to, he said, but they will force me to if I stay.

She knew. She had seen boys being dragged down the street, people averting their eyes. But she did not want him to leave.

He told her he wanted to go to the capital. He asked for money to get there. She would not give it to him, but he stole it and left while she slept. He was a hundred miles from home when the bus skidded off the road and rolled over.

Now the daughter she didn’t want was all she had. The woman was not so much bitter as resigned to her fate; she suspected she was being punished for her thoughts at the girl’s birth. All the furious love the woman had lavished on her sons she now poured on her daughter, and for the first time Precious’s name seemed justified.

The daughter cowered under the assault, after the years in her brothers’ shadows. She had been accustomed to being invisible. Her mother’s attention now seemed like a burden; she missed the airy feeling of being disposable, inconsequential.

The woman did not speak of her sons at home. To the others in the village she bemoaned her losses. But you are lucky, people said. You still have a child. Still alive. Many of us have none left. You are one of the lucky ones.

Yes, she said, I suppose I am.

The woman who had never been afraid now began to fear that her one last child would be taken from her. She tried to hide her daughter, disguise her value, shield her from anyone who might take her away.

She stopped calling her daughter by her name and instead used “Sister.”

Precious did not mind. Her mother seemed determined to name her exactly what she was not.

The woman closed her doors and kept her happiness close and hidden, a miser with her hoard.

The soldier appeared at the door, and before Precious could say a word he cried out how he’d missed her and hugged her to him. He smelled like a week’s worth of sweat, and when he smiled his cheeks stretched into taut creases that looked like they might split at any moment. Don’t you remember me? he said. Of course she didn’t. She’d never seen him before.

He did the same to her mother, embracing her before she could resist. Precious saw her mother’s face, propped on the man’s shoulder, the eyes closed, and for just a moment her mother looked blissful. Then the eyes opened and her mother’s face hardened again.

It’s good to be home, he said.

He’s lying, Precious said sullenly.

Her mother knew it too. And yet she cooked him a meal and allowed him to stay the night. She kept closing her eyes for a few seconds at a time; Precious knew she was imagining that it was true, that one of her sons really had come home.

In the dark of early morning Precious heard a creak and felt a breath on her shoulder. A finger found its way beneath her blanket, it pointed and beckoned. She turned over. And then everything happened fast, before she could say a word, like a gourd cracked open and the pulp scooped out, to be replaced by something else.

In the morning the woman arose to find her imposter son gone and her daughter too. One of them had taken all the money she had.

This is the story the daughter tells to her unseen audience, the listener swaying in a travel hammock made of her own flesh. She tells the story over and over, the rhythm of her voice matching the rocking rhythm of her legs, hoping he will understand.

2. during

“If you’re an illegal,” the man says, “the only absolutely surefire way to get into America is to stow away inside a woman’s belly.”

She asks him what he means. He tells her that anyone born on American soil is automatically a citizen. “Doesn’t matter who or what the parents are.”

“But what happens to the baby’s mother? She’s the mother of a citizen now.”

“Doesn’t matter,” he says. “Anyone without papers, if they catch you they’ll deport you. And they will catch you. Probably take your baby away.”

Her hands slide down the front of her dress.

He narrows his eyes. “You seem determined.” She nods. “Do you know how to swim? Ever been chased by dogs? Can you run fast on those pretty legs?” She nods; she has never done the first two, but surely they are instinctive. Surely, under duress, her body will know what to do.

“Will you still be able to run fast in a month? Two?” he says and with a sudden brisk movement cups his hand against her stomach.

“Yes,” she says, trying not to flinch.

“I might just be able to help you,” he says. “How much money do you have?”

She wants to go to America. She’s heard they give you a free dishwasher the minute you cross the border. In American stores there is always a hundred of everything, food as far as the eye can see, more food than you could eat in a lifetime. There is plenty of work for anyone who wants it, because the Americans are the laziest people on earth and will do nothing they can pay someone else to do for them.

Once you get there, everyone agrees, the rest is easy. Soon you’ll be a lazy American yourself, having fat children and buying furniture. Furniture? Yes, a woman tells her, in America if you want furniture, a refrigerator, even a car, you can pay a tenth of the price and take the things home; the Americans will trust you to pay the rest later. They are as trusting and gullible as children.

The visions of abundance keep her up at night. It’s not for herself that she wants these things. It’s for her baby. She knows he is a son, riding high inside her; with every breath she feels his heels crowding against her lungs.

Months earlier, when she told her cousin she was pregnant, her cousin hugged her and said, “Don’t worry. We’ll take care of it. I know two good ways. One hurts less but takes longer. The other hurts a lot but is over quick. Which do you want?”

“No!” she cried. “Neither,” she said, pushing her cousin away.

She cannot even contemplate getting rid of the baby. She loves him already, has begun crooning to him and addressing conversations to her belly long before she starts to show. But as her son pushes out the front of her dress farther and farther, she begins to wonder. Does she want to raise her son in a country where half the babies die before they are a year old? A country where a woman could have eight children and consider herself lucky if one survives to adulthood?

She begins collecting stories of America. She builds a house in her mind, furnishes it, plants trees outside. She imagines her son, fat and white, playing on a vast expanse of immaculate carpet. She sees him as a boy, big and healthy and strong, wearing stiff brand-new clothes, pushing the other boys so they fall down. She pictures him when he’s her age—by American standards, still a child, he’ll be going to school, playing with his friends, whistling at girls, and trying to put his hand up their short American skirts.

For some reason, whenever she pictures her son he is bald, his head white and oversized and glowing slightly, like an enormous lightbulb. She puts a baseball cap on him. Better.

“You’re crazy,” her cousin says. “They’ll take your baby away and give him to some American parents. They’ll snatch him away the minute you get there and send you back. Americans love foreign babies.”

“Love to eat them,” the cousin’s friend says. “At least that’s what I’ve heard.”

“Do you want your baby taken away and raised by foreigners?” her cousin says.

Of course not, she says, and suddenly realizes she does.

She sees the strange man again and asks if he can help her.

“You want to cross over,” he says. She gives him half a nod.

“You’re in luck. It’s a side business of mine, arranging these things.”

She looks around to see if anyone is listening.

“Just remember,” he says, “there are no guarantees. If they catch you and deport you, I don’t give you your money back. If they catch you, I don’t know you. I’ve never seen you before in my life.”

She nods. The first time she met him he was wearing a flowered shirt and a baseball cap like the one her son wears in her daydreams. Today he is wearing a cowboy hat and a nice-looking suit. When he turns to go she sees that it is all crumpled in the back, riding up into his armpits.

She tries, and fails, to remember his eyes. She thinks he has a mustache.

They meet again so she can give him the money, and he asks for her name.

“Precious,” she says, and looks away. She does not like to reveal her name; she senses it is dangerous for anyone to know her true worth. Precious is the name of someone treasured, adored. It means there are people somewhere who would gladly pay ransom for her, rescue her from a tower, lay down their lives for her. This is not true, but it is what people assume. She’s afraid he’ll raise his price.

But he grins a wide face-creasing grin. He thinks they’re playing a game, giving themselves nicknames. “Then call me Hopper,” he says. “First name Border. And what about”—he nods at the front of her dress—“what about Junior there?”

She stares back at him stonily refusing to acknowledge anything.

“You know,” he says softly, “they don’t like it. They don’t like this kind of thing.”

“What thing?”

“What you’re trying to do. They see it as an abuse of the system. They’ll try to stop you.”

“I don’t care.”

“Good!” he says, breaking into a smile again. Today he is wearing grease-stained coveralls such as a car mechanic would wear and, beneath it, incongruously, a spotless white dress shirt. In a brisk businesslike voice, he says, “We here at Hopper and Associates have many options to offer the busy traveler. Would you prefer plane, train, boat, or automobile? Business class or coach? Smoking or nonsmoking?”

She turns the choices over in her mind. “I’ve never been on a boat.”

“I’m joking, sweetie.”

“Yes,” she says. “I knew that.”

She sees the border in her dreams: an orange stripe, wide as a road, dividing a desert from horizon to horizon. The border is hot; people run across it screaming in pain, their shoes smoking. The border guards are lined up in pairs on the other side, each pair with a swatch of black rubbery webbing stretched between them. The moment someone reaches their side of the border, two guards snag him and slingshot him back to the other side. The guards are neat and precise; nobody gets through. The people pick themselves up and try again, running across the scalding line. Again and again they are repulsed. Some are flung through the air; some are sent skidding across the border on their faces. The people tire, they are staggering, crawling, propping each other up. The guards continue their work mechanically, occasionally pausing to take a man’s wallet or fondle a woman’s breast before sending them back over. There is something about the guards’ alert, smooth movements that seems familiar, as if she’s seen all this before.

She must work out the timing of the crossing as precisely as possible. If she goes too soon, it will mean spending more time, pregnant and waiting, on the other side. The longer she’s there, the greater the chances the deportation people will catch her and send her back before her son is even born.

But if she waits too long he’ll be born outside the border, on un-American soil, and will never get his baseball cap, his citizenship.

She has told her son about America, told him about her plans. Told him the story of a woman and her seven stolen sons. That’s what you can look forward to, she told him, if we stay. She hopes she can count on his cooperation.

The man, Hopper, doesn’t care about her plans. “You’ll go when I tell you to go,” he says. “You can’t control these things. You have to seize opportunities as they arise.”

She waits and waits. Apparently the opportunities are slow to bubble up. She’s in her ninth month when the time comes. She rides a bus to a border town, arrives at the meeting place.

She and six others cram into a secret space behind a false panel in the back of a delivery truck. There are a few nail holes for air. They are afraid to talk; when one makes the slightest noise the others pinch him, roll their eyes. They are all strangers to one another. Their initial excessive courtesy dissipates with the rising heat. The metal walls are like an oven. One man insists on smoking. The two people on either side of Precious accuse her of taking up too much room.

There are delays; the truck stops and starts, the back door opens and closes. At first they all freeze expectantly every time this happens. But the stops continue. Precious begins to wonder if the driver has forgotten about them and is going about his usual deliveries.

Night falls, they know this when dots of light in the nail holes go out and they are in total blackness. No one lets them out.

The second day is more of the same. One man wants to bang on the walls; they’ve forgotten us, he says. The others restrain him. The heat rises and they squabble silently over the last plastic jug of water.

On the third day they all fall into a stupor, frozen in positions of cramped despair. The only one stirring is Precious’s son, kicking impatiently. On the evening of the third day they cross the border without knowing it.

It is dark again when the truck stops, footsteps approach, the metal door is wrenched back. They blink in the glare of a flashlight as the driver helps them out. He tries to make them hurry but they cannot unfold themselves. He carries them out one by one, like statues in tortured poses, and places them on the ground, where they lie unmoving for a long time and then begin to uncurl as slowly as new leaves unfurling.

They lie on hard earth surrounded by trees. The truck disappears down a dirt track leading back to the highway. They begin to groan and creak and stretch themselves—small things first, fingers and toes. Precious stands up and leans against a tree. She tries walking a few steps. The movement makes something shift within her, then shift again, sinking lower, like the tumblers of a lock falling into place. Good, she thinks. Right on time.

She heads down the track toward the highway. The others call after her, warnings, halfhearted offers of help. She knows they’re glad to be rid of her. She’s a burden, a liability.

She walks along the highway. So far America is a disappointment, bare and empty. It’ll get better, she tells herself. Americans, she knows, are optimistic. She thinks of big white gleaming American hospitals.

She waves at the occasional cars zooming past. She can’t see the drivers’ faces. If she were in their place she wouldn’t stop either, she thinks. Who wants a strange woman having a baby all over your nice clean American car?

But within minutes a car pulls over to the shoulder ahead of her. She clutches her son, tries to walk more quickly. Americans really are friendly after all.

The car is a dull gray, dirty, unremarkable, and she’s close before she notices the heavy wire mesh separating the backseat from the front. The driver has already stepped out of the car and has his hand on her arm before she can think of running.

He helps her into the backseat and drives on. He doesn’t seem surprised to see her, seems to know exactly who she is and what she’s doing. He’s driving in the same direction she’d been heading. At first she thinks he’s going to help her after all; then she realizes that they are heading back to the border, that she’d been pointed in the wrong direction.

She’s still hopeful. Everyone says even when you get caught, they make you stay in a detention center for weeks while they ask you questions and write words on pieces of paper. She’ll have her baby and then go home.

But that’s not allowed to happen. She’s rushed through a series of gates and hallways and waiting rooms, and people ask her questions and eye her belly and hustle her along. Before she knows it she’s sitting in a van with other defeated-looking people who don’t meet her eyes. She recognizes two of the people who shared her secret place in the delivery truck but pretends not to.

This time she can see the border as they cross it. It’s not how she pictured it. Just a fence, a checkpoint on the road. She holds her belly. Her son is shifting around. Not yet, she thinks fiercely. Not yet.

She looks for the Hopper man. She assumes he would have disappeared by now, but no, there he is. “Don’t be mad, little mama,” he says. “I told you there were no guarantees.”

She stamps her foot. The pressure inside her is unbelievable. But she wills her body to hold itself together.

“Tell you what,” he says. “How about I set up another trip for you? Free of charge? Because I’m such a nice guy?”

“Not the truck. The driver was bad. I think he told the border police where to find us.”

“That’s terrible,” the man says. “You just can’t trust anyone, can you? I won’t use him again.”

The second time is on a boat, a huge boat, a cargo ship. She doesn’t know what it’s carrying; the cargo could be anything; it’s packed into truck-sized metal rectangles, stacked up in anonymous piles.

She and twelve others hide in the hold. It’s dank, dark, cramped, but the gentle motion of the boat soothes her; this is what it must feel like for her son, she thinks.

Her son is very still. She worries that he is dead, but she tells herself that it’s only because he’s grown too big, has no room to move. Just a little longer, she thinks, and then you can come out and begin your new life. Some people told her America’s territory extends from its coastline, fifty miles into the ocean. Others have said five miles. She wants to wait for solid land to be absolutely sure.

But they’re stopped almost immediately. She and the others are sought out with flashlights, led up to the deck, and lowered into a smaller boat that speeds them back to the harbor. She would have tried to run, to hide, if not for her son. Any violent motion, she fears, will bring him tumbling out. If she jumped in the water, he might swim right out of her to play in the familiar element.

“My goodness,” the Hopper man says when he sees her. “Are you having twins?”

“Your boat people are bad,” she says furiously. “They told the border people we were there.”

“You don’t say! I certainly won’t be using their services anymore.”

“I think the border people pay them money to turn us in. A price for each person.”

“What makes you think that?”

She has heard people arguing, pointing at her and arguing over whether she should bring the price of one or two.

“We’ll get you over there,” the man says. “I give you my promise. Three’s the charm.”

The next time, she rides in a hiding place built between the backseat and trunk of a small car. They have trouble shutting her in; her belly gets in the way. It seems luxurious, after the first two trips. She has the space to herself. A man and woman sit in the front. On the backseat, inches from her, a baby coos in a car seat. She doesn’t know if it’s their baby or someone else’s, a borrowed prop. Her son shifts irritably, probably sensing the other baby, probably thinking, Now that’s the way to travel.

At the border they’re stopped, the trunk is opened. The panel is ripped away, and for the third time she’s blinking in bright light. She imagines her son beating his fists against the sides of her womb.

Not yet, she thinks, not yet, my son. Just a little longer.

She’s now nearing the end of her tenth month. Her belly is strained to the breaking point, her back aches, her knees buckle. But she’s more determined than ever. And her son seems to be as stubborn as she is.

“Now it looks like quadruplets,” Hopper says.

“He’s going to be an American baby,” she says, through gritted teeth. “Babies are bigger there. A nice big healthy American baby.”

“Is that what he told you?”

“He’s not going to come out until we get there,” she says.

“I’ll do what I can,” he says. “No guarantees.”

She’s been told there are places where you can climb over the fence. There are places where there is no fence, only guards in towers who sometimes look the other way. She’s going to take her chances on her own. Enough of his gambles.

“I wish you the best,” he says, tipping his fishing hat.

She can barely walk; she stumbles, lurching and weaving. Other people look at her and say, “There’s no way. It’s impossible.” She ignores them.

She walks, through scrub brush and rocks and burning sand and stagnant, stinking water. She walks and walks, thinking: American baby. Nice big American baby.

She hears a sound echoing from far away: dogs yelping, frenzied. She can almost hear them calling to one another: There she is, there she is, get her.

They burst over a rise and she can see them, a mob of dark insects growing rapidly bigger, a man with a gun trailing far behind. Has she crossed the border already? It’s impossible to tell.

The first dog runs straight at her. She stands still and waits. It seems nearly as big as she is, a small horse. At the last minute it veers away and circles. All the dogs swarm around her. But they do not touch her. They keep their heads lowered abjectly to the ground. They seem in awe of her big belly.

The fat sweating guard who comes puffing up behind them is not impressed. Soon she’s sitting in a familiar van, heading back.

She’s been carrying her son for over a year now, with no intention of letting him go.

“Now, that can’t possibly be good for him, little mama,” Hopper says. “You should let the little feller out.”

“He’s going to be an American baby,” she says, slowly, as if talking to a child.

“Let me help you,” he says. “I know a man—”

“No,” she says.

“We’ll try another way. I can get you a fake passport.”

“No,” she says. She hobbles back to the border, is stopped by a fence, and begins tunneling under it, clawing the dirt with her fingernails. She’s crawling through, nearly breaking the surface on the other side, when her son shifts, or perhaps instantaneously grows a fraction of an inch, and suddenly she’s stuck. Border guards come and drag her out by her heels. They don’t seem surprised, they seem as if they’ve been expecting her. They look bored, almost disappointed, as if they’d expected her to have a little more originality.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.