Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

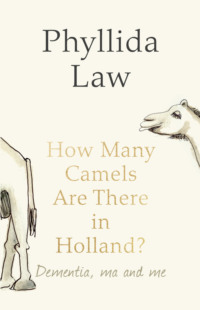

Czytaj książkę: «How Many Camels Are There in Holland?: Dementia, Ma and Me»

For my daughters and the Golden Girls

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

IN THE BEGINNING

DECLINE AND FALL

Copyright

About the Publisher

What is your full name?

How old are you?

When were you born?

What year is this?

What month is this?

What day of the week is this?

What date is this?

What is the name of this place?

What town/city are you in?

What is your mother’s maiden name?

Who is the current PM?

Who was the PM before him?

Without looking at the clock what time is it?

Are you right-handed or left-handed?

Say the names of the months forwards

(January to December). Now backwards.

Count backwards in 7s from 100.

Brief Cognitive Status Exam

IN THE BEGINNING

My mother, Meg, was the seventh of eight children and the youngest of five sisters born to a Presbyterian minister and his tiny indomitable wife, who lived to terrorise us all.

Mother remembered very little about her papa, except that he wore a velvet smoking jacket of an evening and kept a bar of nougat in his breast pocket for little fingers to find. They had sweets only on Sunday when they spent the day in church, eating lunch and tea in the vestry, after which sweets would be found on the church floor, dropped accidentally-on-purpose from velvet reticules by little old ladies.

Papa died young. Grannie went into mourning and took her eight children to Australia, where her brother was a professor at the University in Sydney. Mother was still wearing woollen hand-me-downs. When Grannie became ill the doctor advised a return to a cooler climate. The children were perfectly willing. Ripe mangoes were nice, but locusts were nasty. They took the boat home in 1913. Grannie said there were spies on board, and her beautiful Titian-haired daughters caused havoc among the crew. Aunt Mary got engaged to a sailor, who went down with Kitchener in 1916.

Back in Glasgow, in reduced circumstances, they squashed into a small ground-floor flat near the university and Aunt Lena (who married a millionaire and died on a luggage trolley in Glasgow Central Station) looked after them all. Mother told stories of beds in cupboards and wild nights by the kitchen fire, drinking hot water seasoned with pepper and salt.

The boys went to war and the girls became secretaries. Ma, the youngest, went to a cookery college affectionately known in Glasgow as the Dough School, where she started her career as an inspired cook and learnt to wash walls down before New Year with vinegar in the rinsing water. Then she joined her sisters at the Glasgow Herald offices where she met my father.

He must have been a stumbler for a girl. Handsome, gifted and wounded in the First World War, I think he had what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. I don’t know when Ma ripped her mournful wedding pictures out of the family album, but seven-year-olds are perfectly able to recognise unhappiness.

I only met Father properly years later, after he had eloped with his landlady’s daughter, but I was eighteen by then and it was too late for love.

I remember 3 September 1939 and the outbreak of war. We were to be evacuated. It sounded painful and some of it was. At school we were just ‘the evacuees’, ‘wee Glasgow keelies’, and they snapped the elastic on my hat till my eyes watered. I caught fleas and lost my gas-mask. James, my brother who was twelve, wet the bed, got whacked with a slipper and ran away back to the bombs. I was left behind. My mother and my brother were now half-term and holiday treats. Thinking about it now, I feel bereft. I missed such a lot of warmth. Mother was good at warmth. She always had a gift for dispelling gloom, a useful talent in 1940s Glasgow, which must have attracted Uncle Arthur who, though witty, had a dark side. He used to cheer himself up with the aunts – their brother John was his best friend – but they were all spoken for, so when Mother was divorced he came courting.

She had taken a job in a ladies’ boutique called Penelope’s, opposite Craig’s tea-rooms and next to the Beresford Hotel on Sauchiehall Street. Here she kept the accounts in a huge ledger in a very neat hand, wearing a very neat suit.

On Saturday, she served everybody in the back shop delicious savoury baps before she locked up. I loved the back shop, where Mother removed Utility labels from clothes and replaced them with others she had acquired. Now and again, if she came by a good piece of meat, she would sear it on a high flame on the single gas ring, wrap it in layers of greaseproof paper, a napkin and brown paper and send it by post to anyone she thought deserving at the time.

Arthur and Ma married when I was thirteen and away at boarding school in Bristol. They were very happy. Mother had discovered that men can be funny. If ever I was in a position to phone home, they were never being bombed. Instead they were playing riotous games of ‘Russian’ ping-pong.

One bomb did bring down all the ceilings in the close stairwell with such a rumbling crash that Joey the budgerigar flew up the chimney and never came down again.

Whatever was happening, Ma always travelled down to Bristol at half term wearing an embarrassing hat on loan from Penelope’s. If there was a patch of blue in the sky large enough to make a cat’s pyjamas, she would let out piercing yelps, ‘Pip-pip’, and sing in the street. She also got me seriously tipsy on scrumpy, which she thought sounded harmless.

She and Uncle Arthur moved from their flat to look after Grannie in Aunt Lena’s enormous house, where they grew vegetables and longed for their own plot. Every holiday we went for long drives into the country to find the cottage of their dreams. We never found it. Not till I’d married and had a baby.

My husband and I met at the London Old Vic when we ‘walked on’ in Romeo and Juliet. I was a Montague. He was a Capulet. We didn’t speak much. But later we all had a very good time at one of the early Edinburgh Festivals, and joined a company that toured the West Country in a bus that held our sets and costumes; we ended up at the Bristol Old Vic in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when we proposed to each other. I was Titania. He was Puck.

We got married on a matinée day. Mother bounced into my bedroom that morning, wearing a hat that looked like a chrysanthemum. ‘If you don’t want to do this, darling,’ she said, ‘we’ll just have a lovely party. It’ll be fine.’ I felt that explained her mournful wedding photos. No one had offered her an escape route.

It was May. The sun shone. Uncle Arthur gave me away and Mother blew kisses at the vicar. Then the family party, with assorted aunts, drove to France and we went to give a performance.

I wonder what it was like.

We found a flat in London where you filled the bath with a hosepipe from the kitchen tap. We were happy and in modest employment. My new husband took a job as a ‘day man’ backstage at Sadler’s Wells.

Two years later, we had our daughter Emma. It was April. Just in time for the holidays. We had a phone call from Ma. ‘I’ve taken a house on the Clyde,’ she announced, like an Edwardian matron. ‘I want the baby to start life in good fresh air.’

The weather was appalling. The sea and the sky merged in battleship grey, chucking water at the windows, and our landlady was an alcoholic, who hid our cheques and had regular visits from the police. We took our tin-can car along the purple ribbon of a road that led to the village of Arden-tinny, asking at every BandB if they had room for us. They did, but they were too expensive. Then the wind changed and the weather was sublime. We stopped at the Primrose tea-rooms in the village for an ice-cream, and I sat on the jetty with the baby, dangling my feet in the loch and nibbling a choc ice.

My husband wandered away down the village street to find the phone box, saying that Mrs Moffat in the tea-rooms had told him there were rooms to let in a cottage close by. I had barely finished my ice when he came thundering back down the road at uncharacteristic speed. ‘We’ve got it,’ he said. ‘It’s five pounds for a fortnight. Go and look. Give me Em.’ As I left he called, ‘It’s not the prettiest cottage. It’s the one next door.’

Well – The prettiest cottage was empty.

The prettiest cottage was for sale.

The prettiest cottage was exactly what Uncle Arthur and Ma had been searching for for more than a decade.

We pooled our resources and bought it.

The cottage has had nine lives already. Mother and Uncle Arthur outgrew it and moved to an old manse a short trot along the shore road, where they cultivated their vegetable patch and their soft-fruit cage.

In their eighties it became too much for them. Should they move back to the cottage?

Mother was excited.

Uncle Arthur was depressed.

Moving house didn’t help, I suppose. The idea to scale down and live in the cottage had been mooted, applauded and discarded at my every visit, year after year. The morning room became a dump for ‘stuff’. Old mattresses, an ancient TV, worn-out bedding and pillows, old saucepans and a toaster, a gramophone, gardening tools, two fishing rods and one galosh.

Mother’s confidence was gradually dented by falls on the stairs, with coffee in one hand and a portable wireless in the other. Uncle Arthur just fell down backwards. Then there was the discovery we made, while investigating a damp patch in Ma’s bedroom, that the roof void was full of bats. They would squeeze through a chink in the plaster round one kitchen pipe and very slowly move down, paw over paw, till Uncle Arthur caught them in a dishcloth and threw them out. Any remarks about protected species did not go down well.

He was ruthless with mice. He put stuff under the sink that looked like black treacle and the mice got stuck in it, like flies on fly-paper, whereupon he lifted them by the tail and flushed them down the outside loo. And that was another thing: no downstairs loo, except the one outside. Tricky.

Then there was the car and the undoubted skill needed to park it off the road and up the steep drive, then some very dodgy manoeuvres to get down again. And there was the time they were struck by lightning. Both phones blew off the wall, filling the house with acrid smoke, and four neat triangular flaps appeared on the lawn, as if someone had lifted the turf with a sharp blade. Spooky.

That New Year the Rayburn exploded. The kitchen walls and every surface were coated with black oil that took three days to lift, and Uncle Arthur, trying to be helpful, threw himself on to the fire in the sitting room along with a log. Sage discussions took place over arnica and quite a lot of whisky. They would move to the cottage in the spring, they agreed, but by the time I left for London, the kitchen was as good as new and they had changed their minds. There was no question of their ever leaving the old place.

That very week I signed a contract to appear in La Cage aux Folles at the London Palladium.

Exciting!

Mother rang that evening.

They had sold the house. It was a bad moment. I don’t sob a lot – well, I do now, perhaps, but I didn’t then. Too vain. My nose would swell to the size of a light bulb. It still does, but now I don’t care.

My agent must have been surprised to hear me on the phone after hours and inarticulate, hiccuping with shock.

‘This is not some flibbertigibbet actressy thing,’ I managed to yelp. ‘This is serious.’ She took it as such, tried to get me released and failed. The American producers said I would have to pay for all the printed publicity if I left, but I would be allowed to negotiate a week’s holiday to include Easter weekend, which extended it a little. My stand-in was alerted and I bet she was good. No one complained. They didn’t miss me at all. That’s always a worry.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.