Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

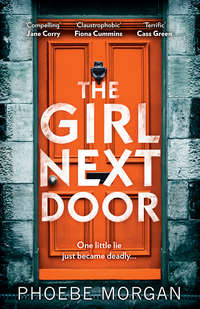

Czytaj książkę: «The Girl Next Door: a gripping and twisty psychological thriller you don’t want to miss!»

PHOEBE MORGAN is an author and editor. She studied English at Leeds University after growing up in the Suffolk countryside. She has previously worked as a journalist and now edits crime and women’s fiction for a publishing house during the day, and writes her own books in the evenings. She lives in London and you can follow her on Twitter @Phoebe_A_Morgan, or visit her website at www.phoebemorganauthor.com for tips on writing and publishing. Her debut novel, The Doll House, was a #1 ebook bestseller. The Girl Next Door is her second psychological thriller.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Phoebe Morgan 2019

Phoebe Morgan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008314859

Version: 2019-02-22

Praise for Phoebe Morgan

‘A real page-turner, I loved this story.’

B A Paris, bestselling author of Behind Closed Doors

‘Tense, suspenseful and unsettling!’

Lisa Hall, bestselling author of Between You and Me

‘Unsettling, insightful, evocative and poignant, Morgan’s writing is both delicate and devastating.’

Helen Fields, author of Perfect Remains

‘A brilliantly creepy and insightfully written debut. I tore through it.’

Gillian McAllister, Sunday Times bestselling author of Everything But the Truth

‘Totally engrossing from start to finish. A clever, clever book.’

Amanda Robson, author of Obsession

‘Morgan’s intense prose grips and thrills from the first page… a terrific debut.’

S. R. Masters, author of The Killer You Know

‘Atmospheric, dark and haunting, I could not put this book down.’

Caroline Mitchell, USA Today bestselling author

‘Deliciously creepy, genuinely unnerving and incredibly confident, The Doll House is the stellar first outing of a major new voice.’

Catherine Ryan Howard, author of Distress Signals

‘Unnerving and spine-chilling.’

Mel Sherratt, million-copy bestselling author

For my family, and for Alex.

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Acknowledgements

Extract

About the Publisher

Prologue

Clare

Monday 4th February, 7.00 a.m.

I’m not coming home tonight. The thought hits me as soon as I wake up, fizzing excitedly inside my brain, like one of those sherbets Mum used to buy me from miserable Ruby’s corner shop. I won’t be sleeping in this bed, I won’t be wearing these red and white pyjamas, I won’t be by myself.

It’s so cold outside; I can see misted condensation on the windows of our house and the room has a filmy, damp feel because Ian’s so bloody tight about the heating. Under the duvet, I wiggle my toes to warm up and reach an arm out for my iPhone, on charge by the side of the bed like it always is. Three new messages – two from Lauren, and one from him. The smile cracks open my face as I read it, and I feel a little shiver of anticipation run through me. Today’s the day. I have been keeping my secret to myself all weekend, but tonight, I’m going to tell him. He’s waited long enough.

‘Clare? Are you out of bed yet?’

Mum’s calling me from downstairs, I can hear Ian thudding around, making too much noise as he always does. Their bedroom is down the corridor from mine, but I never go in there. I hear the shower spray on, the sound of water hitting tiles, then his whistling begins – out of tune, like always. It’ll be like this until the front door slams and he goes to work; until then, the house is full of his loud voice and Mum’s anxious fussing. I’ve got an alarm, of course, but she insists on shouting for me every morning as though I’m six, not sixteen. Reluctantly, I swing my legs over the edge of the bed, wincing as the freezing floorboards touch my feet. My phone, still in my hand, vibrates again and I feel another bubble of excitement, deep in my stomach. Just the day to get through and then it’ll be time. I can’t wait to see his face.

Chapter One

Jane

Monday 4th February, 7.45 p.m.

I’m sitting in the window with a glass of cool white wine, watching as one by one, the lights in the house next door to ours flicker on. It’s dark outside, the February night giving nothing away, and the Edwards’ house glows against the gloom. Their walls are cream – not a colour I’d choose – and their front garden runs down to the road, parallel to ours. Inside, I imagine their house to be a mirror image of my own: four spacious bedrooms, a wide, gleaming kitchen, beams that date from the fifteenth century framing the stairway. I’ve never been inside, not properly, but everybody knows our properties are the most sought-after in the town – the biggest, the most expensive, the ones they all want.

There’s a creaking sound from upstairs – my husband Jack, moving around in our room, loosening his tie, the clunk of his shoes dropping onto the floor of the wardrobe. He’s been drinking tonight – the open bottle of whiskey sits on the counter, sticky drops spilling onto the surface.

Quietly, so as not to wake the children, I stand, move away from the window and begin clearing it up, putting the bottle back in the cupboard, wiping the little circle of stain off the marble countertop. Wiping away the evidence of the night, of the things he said to me that I want to forget. I’m good at forgetting. Blanking the slate. Practice makes perfect, after all.

The house is tidy and still. The bunch of lilies Jack bought me last week stand stiff on the windowsill, their large pink petals overseeing the room. Apology flowers. I could open up a florist, if it wasn’t such a tacky idea.

There’s a sound outside and, curious, I move to the front window, lift the thick, dove-grey curtain to one side so that I can see the Edwards’ front garden. Their porch light has come on, lighting up the gravel driveway, the edge of their garage on the far side, and the stone bird bath at the front, frozen over in the February chill. I’ve always thought a birdbath was a little too much, but each to their own. Rachel Edwards’ tastes have never quite aligned with mine.

We’ve never been close, Rachel and I. Not particularly. I tried, of course. When she and her first husband Mark moved in a few years ago, I went round with a bottle of wine – white, expensive. It was hot, July, and I imagined us sitting out in the back garden together, me filling her in about who’s who in the town, her nodding along admiringly when I showed her the wisteria that climbs up our back wall, the pretty garden furniture that sits around the chinenea on the large flagged patio. I thought we’d be friends as well as neighbours. I pictured her looking at me and Jack wistfully, envying us even – popping round for dinner, exclaiming at the shine of the kitchen, running a hand over the beautiful silver candlesticks when she thought I wasn’t looking. We’d laugh together about the goings-on at the school, the lascivious husbands in the town, the children. She’d join our book club, maybe even the PTA. We’d swap recipes, babysitter numbers; shoes, at a push.

But we didn’t do any of those things. She took the wine from me, naturally, but her expression was closed, cold even. My first thought was that she was very beautiful; the ice queen next door.

‘My husband’s inside,’ she’d said, ‘we’re just about to have dinner, so… Perhaps I can pop round another time?’

Behind her, I caught a glimpse of her daughter, Clare – she looked about the same age as my eldest son, Harry. I saw the flash of blonde hair, the long legs as she stood still on the stairs, watching her mother. She never did pop round, of course. For weeks afterwards I felt hurt by it, and then I felt irritated. Did she think she was too good for us? The other women told me not to worry, that we didn’t need her in our little mothers’ group anyway. ‘You can’t force it,’ my friend Sandra said. Over time, I let it go. Well, sort of.

When Mark died, I went round to see Rachel, tried again. I thought she must be terribly lonely, rattling around in that big house, just her and Clare. But even then, there remained a distance between us, a bridge I couldn’t quite cross. Something odd in her smile.

And then, of course, she met Ian. Husband number two. After that, I stopped trying altogether.

I see Clare every now and then, grown even prettier in the last few years. Jack thinks I don’t notice the way his eyes follow her as she walks by, but I do. I notice everything.

I hear footsteps on the gravel, and recoil from the window as a figure appears, striding purposely towards our front door. I open it before they can knock, thinking of my younger children, Finn and Sophie, tucked away upstairs, dreaming, oblivious.

Rachel is standing on our doorstep, but she doesn’t look like Rachel. Her eyes are wide, her hair all over her face, whipped by the wind.

‘Jane,’ she says, ‘I’m sorry to bother you, I just—’ She’s peering around me, her eyes darting into our porch, where our coats are hanging neatly on the ornate black pegs. My Barbour, Jack’s winter coat, Harry’s scruffy hoodie that I wish he’d get rid of. Finn and Sophie’s little duffels, red and blue with wooden toggles up the front. Our perfect little family. The thought makes me smile. It’s so far from the truth.

‘Have you seen Clare? Is she here?’

I stare at her, taken aback. Clare is sixteen, a pupil at Ashdon Secondary. The year below Harry, Year Eleven. I see her in the mornings, leaving for school, wearing one of those silky black rucksacks with impractically thin straps. She can’t possibly get all her books in there.

Like I said, we don’t mix with the Edwards much. I don’t know Clare well at all.

‘Jane?’ Rachel’s voice is desperate, panicked.

‘No!’ I say, ‘no, Rachel, I’m sorry, I haven’t. Why would she be here?’

She lets out a moan, almost animalistic. There are tears forming in her eyes, threatening to spill down her cheeks. For a moment, I almost feel a flicker of satisfaction at seeing the icy mask melt, then squash the thought down immediately. Just because she’s never been neighbourly doesn’t mean I have to be the same.

‘She’s not with Harry or something?’

I stare at her. My son is out, a post-match pizza night with the boys from his football team. He took Sophie and Finn to school today for me; the night out is his reward. If I’m honest, I’ve always thought he might have a bit of a crush on Clare, like father like son, but as far as I know she’s never given him the time of day. Not that he’d tell me if she had, I suppose. His main communication these days is through grunts.

‘No,’ I say, ‘no, she isn’t with Harry.’

Her breath comes fast, panting, panicked. ‘Do you want to come inside?’ I ask quickly. ‘I can get you a drink, you can tell me what’s happened.’

She shakes her head, and I feel momentarily put out. Most people in Ashdon would kill to see inside our house: the expensive furnishings, the artwork, the effortless sense of style that money makes so easy. Well, it’s not totally effortless, of course. Not without its sacrifices.

‘We can’t find her,’ she says, ‘she didn’t come home from school. Oh God, Jane, she’s disappeared. She’s gone.’

I stare at her, trying to comprehend what she’s saying. ‘What? I’m sure she’s just with a friend,’ I say, putting a hand on her arm as she stands at the door, feeling her shake beneath my fingers.

‘No,’ she says, ‘no. I’ve called them all. Ian’s been up and down the high street, looking for her. She’s normally home by four thirty, school gets out just after four. We can’t get hold of her on the mobile, we’ve tried and tried and it goes to voicemail. It’s almost eight o’clock.’ She’s clenching and unclenching her fists, blinking too much, trying to control the panic. I don’t know what to do.

‘Shall I come round?’ I ask. ‘The kids are asleep anyway, Harry’s not here, and Jack’s upstairs.’ If she thinks it odd that my husband hasn’t come down, she doesn’t say anything.

‘Rachel!’ There’s a shout – Ian, the aforementioned hubby number two. He appears in my doorway, a large, oversized iPhone in his hand. His face is red, he looks a bit out of breath. He’s a big man, ex-army, or so people say. Works in the City, takes the train to Liverpool Street most mornings. I know because I see him through the window. He runs his own business, engineering, something like that. Always a jovial tie. I’ve heard him shouting at Clare in the evenings; I can never make out what he’s saying. I suppose it must be hard, being second best. I know I wouldn’t like it.

‘The police are on their way,’ he says, and at this Rachel breaks down, her body curling into his, his arms reaching out to stroke her back.

‘If there’s anything I can do,’ I say, and he nods at me gratefully over his wife’s head. I can see the fear in his own eyes, and feel momentarily surprised. It takes a lot to unsettle a military man. Unless he knows more than he’s letting on. He never did get on well with Clare.

Chapter Two

DS Madeline Shaw

Monday 4th February, 7.45 p.m.

‘It’s my stepdaughter, Clare. She hasn’t come home from school.’

The call comes in to Chelmsford Police Station just after 7.45 p.m. on Monday night. The team are polishing off a tin of Quality Street left over from Christmas; DS Ben Moore is hoovering up the strawberry creams while DS Madeline Shaw targets the caramels. It’s the DCI who answers the phone, holds up a hand to silence the room.

When she sees the look on Rob Sturgeon’s face, Madeline picks up the handset, presses the pads to her ears. Ian Edwards’ voice is gruff, but she can hear the urgency in it that he’s trying to control. Immediately, she knows who he is – the Edwards family live in Ashdon, in one of the big detached houses off Ash Road. His wife Rachel works at the estate agency in Saffron Walden. She’s got one child from her first marriage: Clare. Madeline lives three streets away from her: they are practically neighbours.

‘She’s normally home long before now, school finishes at ten past four,’ Ian says, his words coming fast. ‘I’m afraid my wife is getting a bit worried.’ A pause. ‘We both are.’ DS Moore is making a face, delving back into the chocolate, but Madeline listens carefully. The DCI is asking questions, his voice calm – how old is Clare, when did you last see her, when did you last hear from her.

‘We’ve tried her phone, dozens of times now,’ Ian says. ‘It’s just going to voicemail. It’s not like her to do this—’ He breaks off.

Madeline is about to chip in, to tell Mr Edwards that she can come round – after all, she’ll be going home anyway – but the door to the MIT room swings open and Lorna Campbell pops her head round the door, her coat on even though she normally works until eleven.

‘Detective Shaw?’

Madeline slips off her headset. ‘Everything okay?’

Lorna raises her eyebrows at the team. ‘Report just in of a body found in Ashdon, in the field at the back that borders Acre Lane. Female victim. Guy called Nathan Warren phoned it in, says he was out walking, stumbled across her. You ready?’

The DCI’s face changes. Wordlessly, Madeline follows Lorna outside.

The girl is lying on her back in Sorrow’s Meadow. In the summer, despite its miserable name, the field is full of buttercups, bright yellow flowers shining in the sun, but in the winter it’s dark and barren. Clare Edwards’ golden hair is fanned out around her head like a halo, blood is soaking into the frosty grass around her skull. Madeline’s torch beam picks out the places where it’s already darkened, highlights the silvery trail of saliva that has frozen on the girl’s cheek. It’s freezing, minus two. She’s in her school uniform: jumper and skirt, a scarf and a little blue puffer coat over the top.

‘Call forensics,’ Madeline tells Lorna, her breath misting the air, little white ghosts forming above the body.

‘They’re on the way already,’ Lorna says, ‘the DCI too.’

‘Clare,’ Madeline says aloud, but it’s pointless; when she bends to touch the girl’s neck, her gloved fingers meet ice-cold skin, no hint of a pulse. For a moment, the policewoman looks away. She’s never had a case where she knew the victim before, even though her interaction with Clare Edwards has only been brief. A school assembly last December; Madeline had been called in by the head to do a routine safety chat. Clare had approached her afterwards, wanted to know more about her job, a career in the police. It had surprised her, at the time. Now, it makes her feel sick. Clare’s future is gone, over before it began.

The forensic team arrive and begin sealing off the area, their white suits bright in the darkness.

Gently, Madeline lifts the blonde hair, exposing the wound at the back of Clare’s head.

‘She looks so young,’ Lorna mutters quietly, and Madeline nods.

The torchlight lands on her rucksack, a black faux-leather bag, thin straps. Inside are a pile of school books; her name is all over everything, the neat blue handwriting re-emphasising Clare’s youth.

‘No mobile phone.’ Lorna hands her Clare’s wallet – a purple zip-up from Accessorize. Carefully, Madeline thumbs through her cards: her provisional driver’s licence, a Nando’s loyalty card, plus an old Waterstones receipt, long out of date.

‘Shaw. I’ve been on the phone to her mother. Fill me in.’

DCI Rob Sturgeon appears at her side; quickly, Madeline begins sliding the exercise books into evidence bags, turns to face him.

‘Have you told her yet?’

He shakes his head. ‘No, not until we’ve formally ID’d. Shit.’ He runs a hand through his hair. ‘Is Alex here?’

They both look around, and spot DS Alex Faulkner a few metres away, talking to one of the forensics team.

‘Faulkner!’

At the DCI’s shout, Alex heads over, the expression on his face grim.

‘Looks like someone’s repeatedly slammed her against the ground,’ he says, nodding to Madeline. ‘Back of her head’s not a pretty sight.’

There is a blue ink stain all over Clare’s left hand, and her unpainted fingernails are dirty, from where she’s presumably clawed at the ground.

‘You don’t think there was a weapon?’ the DCI says, and Alex shakes his head. ‘Doesn’t look like it to me.’

‘Suggests unplanned, then,’ Madeline adds, and he nods.

‘Quite possibly. Fit of anger, perhaps. Crime of passion.’ There’s a pause. ‘We’ll be testing for rape, of course.’ He swallows, spreads his hands in the semi-darkness. ‘Or else it was planned, and our killer just decided to cut out the middle man. Less evidence that way.’

‘Someone who trusts their own strength, in that case,’ Rob says. The guys are placing markers on the frosty ground, marking the places Clare’s blood has spilled. Trusts their own strength, Madeline thinks. Nine times out of ten it’s a man.

‘You said Nathan Warren phoned it in?’ she asks Lorna, frowning.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ Lorna says, and catching the expression on her colleague’s face, ‘d’you know him?’

‘Yes,’ Madeline says slowly, stepping to one side as they begin to erect a little white tent over her body, looking out to where the stile leads to the footpath down to the town centre, ‘I do know him. I know exactly who he is.’

Clare Edwards is pronounced dead at 8.45 p.m. Madeline closes her eyes, just briefly, remembering the day Clare spoke to her at the school, their conversation in one of the empty classrooms, the curiosity in her eyes as she asked Madeline what being a police officer was really like. How can that girl be lying here on the floor, pale and lifeless? The two images will not connect in her brain.

‘I want you with me, Shaw,’ the DCI says, breaking the memory. ‘Let’s get this over with, for God’s sake. Keep the tent up,’ he barks, his eyes scanning the meadow, ‘we don’t want anyone seeing this.’ Gloved hands are combing the ground for her phone, lights are picking out the spots of blood in amongst the leaves. The blood on her head is darker now, dry and blackening. Madeline’s mind is already on Mr and Mrs Edwards, knocking on their front door, ready to deliver them the worst news of their lives.

‘We can walk there,’ she says at last, ‘it’s only ten minutes.’

‘Right,’ Rob says, ‘Campbell, Faulkner – update me soon as you can. Send a car after us to the house, we’ll need a family liaison officer. I want everyone on this. Jesus, sixteen. The press’ll have a bloody field day.’

Madeline leads the way, back across Sorrow’s Meadow, out of the wooded area and down Acre Lane towards where Ashdon High Street meets the river. The small town is quiet; it’s a Monday night. Driving through, you’d have seen nothing, heard nothing. The Edwards house looms in front of them, one of a pair set back slightly from the road, and the DCI puts his hand on her arm at the edge of their drive: a gravel affair, primroses either side, stiff with the cold. There’s a bird bath to the left, frozen solid in the February air. Madeline looks to the house next door, separated from the Edwards’ by a thin grass strip. Lights off, except for one. The Goodwins’ place. Both houses are huge in comparison to Madeline’s; security systems glow in the darkness. Behind the garage doors lurk expensive, silent cars.

‘Just the basics for now,’ Rob says, ‘until we have the full picture.’

‘Are we mentioning Nathan Warren?’

Madeline’s question goes unanswered; the door opens before either of them can even knock and then there they are, framed before the police in the bright light of the house, Rachel Edwards and her husband Ian. Rachel looks like Clare – that same striking face, beautiful without needing to try. They recognise her from the town; she can see the flash of hope on their faces. Madeline steps forward.

‘Mr and Mrs Edwards. This is DCI Rob Sturgeon, my colleague at Chelmsford Police Force. We have news on your daughter. May we come in?’