Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

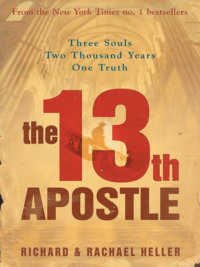

Czytaj książkę: «The 13th Apostle»

Richard Heller and Rachael Heller

The 13th Apostle

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are

the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual

persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

A Paperback Original 2007

THE 13TH APOSTLE. Copyright © Dr Richard Heller and Dr Rachael Heller 2007. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Richard and Rachael Heller assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 9781847560407

Ebook Edition © September 2008 ISBN: 9780007236909

Version: 2018-05-17

The 13th Apostle is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors’ imaginations or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, or organizations, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

As each character, organization, or institution is either fictional or portrayed in a purely fictional manner, the perceptions, beliefs, motivations, actions, beliefs, portrayals, and histories of each character, organization, or institution should be considered products of the authors’ imaginations and should not be construed as reflecting any aspect of reality. In the same way, character’s perceptions, motivations, actions, beliefs, and histories do not, in any way, reflect the perceptions, motivations, actions, beliefs, or histories of any organization or institution, nor do they reflect the perceptions, motivations, actions, beliefs, or histories, of any character’s religious, ethnic, racial background, affiliation, or national origin.

Dedication

To Charles D. Besford,

For his fine mind, caring heart,

and generosity of spirit.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three

Fifty-Four

Fifty-Five

Fifty-Six

Fifty-Seven

Fifty-Eight

Fifty-Nine

Sixty

Sixty-One

Sixty-Two

Sixty-Three

Sixty-Four

Sixty-Five

Sixty-Six

Sixty-Seven

Sixty-Eight

A Conversation With the Authors

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Among the most sacred of texts it is written:

In each generation there are born thirty-six

righteous souls who, by their very existence,

assure the continuation of the world.

According to Abraham’s Covenant, once each

millennium, God shall return to earth and count

among the many, those who remain righteous.

Were it not for these tzaddikim, the righteous ones,

who stand in God’s judgment, mankind’s fate would

be in grave and certain peril.

These tzaddikim have no knowledge of each other;

neither have they an understanding of their own

singular importance. As innocents, they remain

unaware of the critical consequences of their

thoughts, their faith, and their deeds.

Save for one.

To this tzaddik alone, is the granted knowledge

of his position, for to him is entrusted the

most sacred of tasks.

PROLOGUE

Six months ago, London

Professor Arnold Ludlow opened the ancient diary. The musty smell filled him with excitement. This was the manuscript that had eluded him for four decades, its existence supported by a few obscure references and unsubstantiated rumor. Still, he had not lost faith. Now he held it in his hands and translated, from the Latin, the words of one long dead.

The Courtyard of Weymouth Monastery

The First day of May 1097

There was no stake onto which the monks might secure the prisoner, so Father Abbot John gave orders that the heretic be tied to the great elm. The tree was half-dead, having been struck by lightning last spring. One half of the trunk had turned to dry, brittle wood and would provide a quick hot flame at the start. The other half had exploded with new green growth and would now ensure a constant renewal of the flames of salvation. With the application of enough oil to the dry wood, the fire would burn steadily enough to allow the prisoner to renounce his heresies and so, at the last moment, snatch his soul from the waiting hand of the devil.

With the conclusion of evening vespers, novice-master and three novitiates fetched the prisoner from his cell. The heretic walked among them, head held high, eyes forward. He did not protest as others had; neither did he beg for mercy.

Under the watchful eye of their instructor and the monastery’s full register of monks—more than a score in all—the three novitiates bound the heretic to the tree, hand and foot. Each took a turn, loosening the coarse jute, then pulling it taut. With every tightening, small pieces of flesh were torn from the prisoner’s wrists and ankles, leaving small rivulets of red in their wake.

The other monks drew closer and watched in silence. From time to time, each nodded his approval and, in solemn tones, expressed his hope for the heretic’s repentance. Yet, even, as they watched the novices secure ropes around the prisoner’s neck, waist, then across his groin, their breathing quickened. Although weighted down by heavy robes, Brother Jeremiah, the youngest of the monks, appeared to be greatly aroused.

At novice-master’s nod, each of the monks, in turn, made his way to the shed and returned with a large bundle of faggots so that each, by his contribution, might share in the glory of the redemption.

The parcels of sticks were placed carefully around the feet of the heretic, then piled high to his waist. The packing of the wood was critical. If faggots were too lightly mixed with straw, the fire might go out, requiring a second or third attempt; wood too densely packed would produce a fire so hot that it might bring too rapid a surcease of pain. Much practice and skill was required in order to produce the perfect flame with which to burn a man alive.

And still the prisoner stood motionless.

In silence, the monks prayed for the heretic’s soul. Only one among them did not.

I, alone, prayed for a miracle; some divine intervention that might spare the man whose soul needed no redemption; this brave knight who had fought so valiantly in the Holy Land and who now offered up his life, yet again, in service to God and his fellow man.

Head still bowed, I ventured one quick glance. Tears flowed from the prisoner’s eyes, yet he offered no protest. Though I stood well within his gaze, he did not look in my direction.

Guided by novice-master’s hand, the oldest of the novitiates ladled oil about the great pile of faggots, careful to spoon the greatest portion over the bottommost sticks, diminishing the application as he approached the top of the pile. The oil had been freshly rendered only that morning from the fat of the foulest of slaughtered livestock, a peasant’s old pig, diseased and pocked, that had gone to its death squealing in pain and terror, in full earshot of the prisoner’s cell.

Two rags soaked up the remainder of the oil. These novice-master used to anoint the heretic. As he smeared the foul-smelling viscous fluid over the prisoner’s bare shoulders and shaven head, he continued his instructions to his charges. The oil must be smeared evenly over the exposed flesh so as to encourage the start of a flame, then soaked into the jute to sustain the burning.

Amidst the instruction, the heretic continued in silence.

Novice-master signaled the novitiates to retreat, then stepped back to join the monks’ circle.

All waited, eyes cast toward the sky. In accordance with the Inquisitor’s Dictates for Redemption, the fire would be started at the moment when the light of the first star pierced the night. I beseeched God that, although the skies would grow dark, no star would appear. And for a time none did.

In the fading light, three birds flew across the horizon and disappeared into the heavens, one leading the two. They called loudly into the approaching night, one to the other, staying in perfect formation, flying as one. I knew this to be a sign that One far greater than we mortals waited to guide the prisoner into heaven.

A single star blinked and was gone. This was the signal for which all had been waiting. Father Abbot emerged from the shadows and approached the circle, an oil-soaked torch in one hand, a candle in the other, his eyes fixed upon me.

With sudden terror, it came to me that the Abbot John might command me to light the fire. Could even he require me to enact such a deed in order to prove my fidelity? If so, I could not comply. Though my sacred vows to the Church would be broken, though the repercussions of my rebellion might echo through eternity, this, Dear God, I could not do.

But Father Abbot John had other intentions. He lit the torch with the candle then passed it to one of the other monks, motioning me to remain by his side. It seemed to me that a smile crossed the Abbot’s lips but nothing more was said. Then, in the light of that sputtering candle, he turned so that his prisoner could not fail to witness the only act that might yet bring a cry of repentance. From beneath his robes, the Abbot withdrew the moldering wooden box still wrapped in tattered cloth.

The heretic’s gaze fixed on the bundle and then found me. Only then did I see fear spring to his eyes; fear not for himself but for something far greater, that which lay within the crumbling wooden box. As we had in our youth, I shared with the man they now called heretic a single terror, like none other before. Might the Abbot yet commit an atrocity far greater than the taking of a single innocent life? Might he yet commit a sacrilege against man and against God too terrible to imagine?

Professor Ludlow frowned. Hints, suggestions, intimations. Nothing more. He eyes fell on a small piece of parchment that had been wedged into the hand-sewn binding. It had been hastily written, it seemed, but the ink remained dark and clear.

With care, the Professor inched the hidden message from the binding. He read the words, smiled, sighed deeply, and closed the diary for which he would soon forfeit his life.

ONE

Present day

Day One, early evening

The New York City Grill

In the dim light of the restaurant, Gil Pearson strained to check his watch. He’d give the Professor and Sabbie ten more minutes to show. No more. He was tired and hungry and wanted to go home, grab something to eat, and crawl into bed. This was the last sales pitch dinner that George was going to get him to agree to.

What a way to start a weekend.

“Do this one as a favor to me,” George had cajoled. “You know you’re the reason they come to us. All any client wants is a chance to meet the man who helped rid the world of CyberStrep. You’re a celebrity, for God’s sake. You know they’ll pay triple just to be able to brag to their friends they have you watching over their systems,” George added, trying to appear as endearing as his three chins would permit.

Although Gil hated to admit it, George was right. Since graduating top of his class from Massachusetts Institute of Technology two decades ago, Gil’s anti-hacking discovery had changed the way virtually every major data protection company in the world approached the securing of high-risk and top secret information. For three years running, he had been named Man of the Year by the National Association of Artificial Intelligence, yet no client ever referred to these accomplishments. Only when the New York Times reported that Gil was the creator of the computer program that had eradicated the data-eating virus that held the Internet hostage for almost a month, did anyone take notice. The whole thing might have faded if People magazine hadn’t jumped on the story. They spent three-quarters of the article describing his “rugged good looks” and barely mentioned his work.

Lucy had teased him unmercifully. Within days of the article’s publication, an ever-hungry storm of reporters and paparazzi began to beat a path to his—or rather to CyberNet Forensics, Inc.’s—door.

The company’s worth had gone through the roof, Gil’s salary had more than quadrupled, and he had been dragged, kicking and screaming, from the privacy of his little computer room to the bright lights of celebrity.

That had been four years ago. It couldn’t have come at a worse time. Lucy had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and, though every minute away from her felt like the greatest betrayal he could imagine, Gil had convinced himself that he had to cash in on his fame so that he could pump up his salary while he could. It was the only way he could be sure that Lucy would get the best possible care in the hard times that lay ahead.

A sour taste of bile rose in his throat.

Son-of-a-bitch doctor.

Right from the beginning the bastard had known that Lucy didn’t have more than six weeks left. Had the quack told Gil the truth, he would have spent every precious minute with her. But, instead, the doctor had led him to believe that because of her youth and strength, Lucy’s decline would be unmercifully slow. Months—maybe a year—of painful deterioration were inevitable, the doctor had said; an unthinkable time in which Lucy’s pain could be eased by the best medical care that money could buy.

Instead, she was gone in less than a month, only two weeks before her thirty-fourth birthday. Gil had spent much of that time away from her, in endless interviews, answering asinine questions posed by one stupid reporter after another. Less than a week after it was over, one tabloid cover sported his photo, snapped at the cemetery. The inside copy reported that he was recently widowed and implied that after a suitable time of mourning, he would be an excellent catch.

Gil swallowed against the lump in his throat and forced himself to think about something else.

I’m out of here.

He rose and kicked his chair back hard. As he reached to keep it from falling, something caught his eye.

Gray hair flying, short fat legs waddling, and looking a great deal like the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, Dr. Arnold Ludlow, Professor of Antiquities and consultant on Early Christian Artifacts to the Israel Museum, arrived.

Breathless and dripping, he pealed off his wet raincoat and draped it on his seat back then settled into the chair.

“Sorry I’m late,” he began without introduction. “Your taxis, you know. You can never get one in the rain.”

Gil managed a nod before the Professor continued an account of the many difficulties he’d confronted in a city that seemed bent on preventing him from making this meeting.

“Sabbie didn’t show at the airport but no worries,” Ludlow added, “that’s not unusual for her.”

Gil surrendered to the mounting wave of disappointment. It didn’t really matter anyway. He would sit and wait while the old man prattled on and, when enough time had elapsed so that he could do so without seeming terribly impolite, Gil would reach for the menu.

But he never got the chance.

TWO

A few minutes later

Hotel Agincourt, New York City

Abdul Maluka stepped from the shower and stared at his reflection in the bathroom mirror. Black hair dripping, dark skin glistening in the bright light, he liked what he saw. He was short by Western standards, but every inch of his frame was pure muscle. He patted his flat stomach and surveyed his tan shoulders.

Not bad for an old man of forty.

The crescent-shaped scar across his right cheek was the perfect finishing touch. It made him look interesting. Even…sexy.

He had sustained the injury as a result of one of his father’s infamous thrashings, in this case as a direct result of Maluka’s refusal to stand silently by as his father announced to the family that his advanced age no longer permitted him to participate in the Fast of Ramadan.

“You are well enough to lay with your whore whenever she will tolerate you,” a twelve-year-old Maluka had sneered. “How can you say you cannot keep the Fast?”

His father had attempted to stare the boy down.

Maluka’s mother had been in easy earshot. The older man’s discomfort fueled Maluka’s outrage.

“Surely, you can forgo some pleasure in the name of Allah. Or can you not even wait until the sun sets to bury your face in the flesh of that pig,” the youth had added with a laugh.

His father had ripped the worn brown leather belt from the waist of his Western suit of clothes and had beaten the young Maluka with all the strength he could muster. Only when the boy fell to the floor under the torrent of blows, did his father’s fury subside.

“You are not my real father,” the young Maluka had declared. “My father is the spirit of Islam. The poorest devotee to Allah is more my father than you.”

His father added one final blow for good measure; one the boy would never forget. The sharp edge of the buckle caught Maluka across the cheek and left a gash from which blood poured. It was only then that his father smiled with satisfaction.

“Let your faith heal that for you, boy!” he had said triumphantly, then turned, left, and never spoke of the matter again.

Nearly three decades later, the token left by his father’s fury now declared to the world, proof of Maluka’s commitment to Islam. With age, the wound had transformed into a perfect crescent shape whenever he smiled. Not that he smiled all that often.

Maluka pulled on a pair of finely tailored slacks and selected a new silk shirt delivered fresh from his New York shirtmaker, then entered the living room.

Aijaz Bey looked up guiltily. His bulbous bald head, set on a thick neck and huge shoulders, would have made him look unintelligent even if he were bright—which he was not. At six foot six, weighing two hundred and eighty pounds, he was indeed as dangerous as he appeared—and as obedient; two essential attributes which made him the perfect assistant.

The remnants of torn plastic wrappings, wadded up linen napkins, and empty plates, littered the rolling dining cart. Maluka shook his head in resignation. Although Aijaz’s huge hands were skilled at carrying out whatever delicate act with a knife was required, and his skill with a gun was quite remarkable, the man seemed incapable of removing his dinner from a room-service tray without making a mess.

“Couldn’t wait,” Aijaz explained with a shrug and an obsequious smile.

“No problem.”

Aijaz breathed a sigh of relief.

At the sound of the knock at the hotel door, both men straightened.

Aijaz waited for instruction. Maluka raised his hand and silently signaled him to halt. At the second knock, Maluka nodded and Aijaz opened the door.

Clearly startled by Aijaz’s bulk, the man hesitated, then entered. Though no more than forty years of age, his bent back and the downward thrust of his head betrayed the attitude of a man who had been broken on the rack of life. Tall and gaunt, his gray hair slicked back from an overabundance of grease or sweat, their guest offered his right hand to Maluka in greeting. Seeing that no such gesture was about to be returned, he hesitated, then withdrew his hand.

“Sorry, I guess you chaps don’t shake hands,” he muttered with a nervous laugh. “My error.”

When no smile was forthcoming, he checked his watch.

“Look, I’m sorry if I’m a tad early. I just thought that with the weather being what it is, well, you know, better to be early than late. Of course, if I interrupted something…”

His gaze darted from Maluka to Aijaz and back again, desperate for any indication of how to proceed. Maluka was pleased. Robert Peterson, assistant to Professor Arnold Ludlow, was not going to offer any resistance. It wouldn’t take more than fifteen minutes for Maluka to get all of the information he needed. Twenty at most.