Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

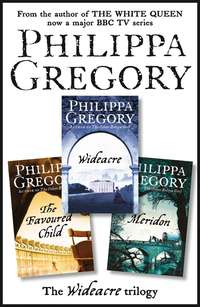

Czytaj książkę: «The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon»

PHILIPPA GREGORY

THE COMPLETE WIDEACRE TRILOGY:

WideacreThe Favoured ChildMeridon

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Wideacre

The Favoured Child

Meridon

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PHILIPPA GREGORY

Wideacre

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Epilogue

Map

1

1

Wideacre Hall faces due south and the sun shines all day on the yellow stone until it is warm and powdery to the touch. The sun travels from gable end to gable end so the front of the house is never in shadow. When I was a small child, collecting petals in the rose garden, or loitering at the back of the house in the stable yard, it seemed that Wideacre was the very centre of the world with the sun defining our boundaries in the east at dawn, until it sank over our hills in the west in the red and pink evening. The great arch it traced in the sky over Wideacre seemed to me a suitable boundary for our vertical influence. Behind the sun was God and the angels; beneath it, and far more significantly, ruled the Squire, my father.

I cannot remember a time before I loved him, the blond, red-faced, loud Englishman. I suppose there must have been a time when I was confined to a white-frilled crib in the nursery; I suppose I must have taken my first steps clinging tight to my mother’s hand. But I have no childish memories of my mother at all. Wideacre filled my consciousness, and the Squire of Wideacre dominated me as he ruled the world.

My first, my earliest childhood memory is of someone lifting me up to my father as he towered above me in the saddle of his chestnut hunter. My little legs dangled helplessly in space as I rose up the yawning void to the great chestnut shoulder – a hot, red rockface to my surprised eyes – and up to the hard, greasy saddle. Then my father’s arm was tight round my body and his hand tucked me securely before him. He let me grip the reins in one hand and the pommel in the other, and my gaze locked on the coarse russet mane and the shiny leather. Then the monster beneath me moved and I clutched in fright. His pace was erratic and rolling to me, and the long gap between each great stride caught me unawares. But my father’s arm held tight and I gradually raised my eyes from the muscled, steamy shoulder of the mountainous horse, up his long neck to his pointy signalling ears … and then the sweep of Wideacre burst upon me.

The horse was walking down the great avenue of beech and oak that leads to the house. The dappled shadows of the trees lay across the springing grass and the rutted mud tracks. In the banks glowed the pale yellow of spring primroses and the brighter sunshine yellow of celandine. The smell, the dark, damp smell of rain-wet earth filled the arch of the trees like birdsong.

A drainage ditch runs alongside the drive, its yellow stones and white sand rinsed clean by the trickle of water. From my rolling vantage point I could at last see a clear view of its length, even where the black leafmould at the banks carried the tiny, forked hoofprints of nighttime deer.

‘All right, Beatrice?’ My father’s voice behind me was a rumble I could feel in my tense, skinny little body as well as hear. I nodded. To see the trees of Wideacre, to smell the earth of it, to be out among the breath of wind of Wideacre, bonnetless, carriageless and motherless, was beyond words.

‘Like to try a trot?’ he asked.

I nodded again, tightening my small hands on the saddle and reins. At once the giant strides altered and all around me the trees lurched and jigged as the horizon moved in great sickening leaps. I bobbed like a cork in a spring-flood river, sliding painfully to one side, and then, perilously, correcting. Then I heard my father click to the horse and the stride lengthened. Wonderfully, the horizon steadied, but the trees sped past. I regained my balance and, though the ground flashed by under the thudding hoofs, I could breathe and look around again. Your first canter is the fastest speed you will ever go. I clung like a louse to the saddle and felt the spring wind in my face, and saw the shadows of the trees flash light and shade across me as the chestnut mane streamed, and I could feel a great burble of delighted laughter and scream of fear gather in my throat.

On our left the woods were thinning and the steep bank dropped away, so I could see through the trees to the fields beyond, already brightening with the spring growth. In one a hare, large as a hound puppy, stood on its hind legs to watch us go by, its black-tipped ears pointed to hear the thud of the hoofs and the jingle of the bit. In the next field a line of women, drab against the deep black of the ploughed field, bent double over the furrows, picking, picking, picking, like sparrows on the broad back of a black cow, clearing the earth of flints before sowing.

Then the sliding scenery slowed and slowed as the hunter dropped into a teeth-chattering trot again, and then pulled up at the closed gates. A woman erupted from the open back door of the lodge house and scuttled through a scatter of hens to swing open a tall iron gate.

‘A fine young lady you have to ride with you today,’ she said smiling. ‘Are you enjoying your ride, Miss Beatrice?’

My father’s chuckle vibrated down my spine, but I was on my dignity, high on the hunter, and I merely bowed. A perfect copy, had I known it, of my mother’s chill snobbery.

‘Say good day to Mrs Hodgett,’ my father said abruptly.

‘Nay!’ said Mrs Hodgett, chuckling. ‘She’s too grand for me today. I’ll have a smile on baking day though, I know.’

The deep chuckle shook me again, and I relented and beamed down on Mrs Hodgett. Then my father clicked to the hunter and the smooth walk bore me away.

We did not turn left down the lane that leads to Acre village as I had expected, but went straight ahead, up a bridle track where I had never been before. My excursions until now had been in the carriage with Mama or in the pony-cart with Nurse, but never on horseback along the narrow green ways where no wheels could go. This path led us past the open fields where each man of the village could farm his own strip in a ragged, pretty patchwork. My father tutted under his breath at the ill-dug ditch and the thriving thistles in one patch and the horse, eager for a signal to canter, broke forward again. His easy strides took us higher and higher up the winding path, past deep banks dotted with wild flowers and with exciting-looking small holes, crowned with hedges of budding hawthorn and dogroses.

Then the banks fell away, and the fields and hedges with them, and we were riding, silent on thick leafmould, through the beech coppice that crowds the lower slopes of our downs. Tall, straight, grey trunks rose high as a cathedral nave. The nutty, woody smell of beech tickled my nose, and the sunlight at the end of the wood looked like the bright mouth of a cave, miles and miles away. The hunter, blowing now, rushed upon it, and in seconds we were out in the brilliant sunlight at the very tipmost-topmost point, the highest peak in the entire world, the pinnacle of the South Downs.

We turned to look back over the way we had come and the shape and the setting of Wideacre opened up to me, like a magical page in a picture book, seen for the first time.

Closest to us, and extending far below us, were the green, sweet slopes of the downs, steep at the top, but easy as soft shoulders lower down. The gentle wind that always blows steady and strong along the top of the downs brought the smell of new grass and of ploughing. It flattened the grass in patches like seaweed tossing under currents of water, first one way, then another.

Where the ground grew steep and broken, the beech coppices had taken hold and now I could look down on them, like a lark, and see the thick tops of the trees. The leaves were in their first emerald growth and chestnuts showed fat, mouth-watering buds. The silver birches shivered like streams of green light.

To our right lay the dozen cottages of Acre village, whitewashed and snug. The vicarage, the church, the village green and the broad, spreading chestnut tree that dominates the heart of the village. Beyond them, in miniature size like crumpled boxes, were the shanties of the cottagers who claimed squatters’ rights on the common land. Their little hovels, sometimes thatched with turf, sometimes only a roofed-in cart, were an eyesore even from here. But to the west of Acre, like a yellow pearl on green velvet, amid tall, proud trees and moist, soft parkland, was Wideacre Hall.

My father slipped the reins from my fingers and the great head of his horse dipped suddenly to crop the short turf.

‘It’s a fine place,’ he said to himself. ‘I shouldn’t think there’s a finer in the whole of Sussex.’

‘There isn’t finer in the whole world,’ I said with the certainty of a four-year-old.

‘Mmm,’ he said softly, smiling at me. ‘You may be right.’

On the way home, he let me ride alone in glorious solitude on top of the swaying mountain. He walked at my side, a restraining hand gripping the frills and flounces of my petticoats. Past the lodge gates and up into the cool quietness of the drive, he loosened his grip and walked before me, looking back to bawl instructions.

‘Sit up! Chin up! Hands down! Heels in! Elbows in! Gentle with his mouth! You want to trot? Well, sit down, tighten the rein, and dig your heels in! Yes! Good!’ And his beaming face dissolved in the heaving blur as I clung with all my small might to the leaping saddle and bit back shrieks of fear.

I rode alone up the last stretch of the drive and triumphantly brought the gentle great animal to a standstill before the terrace. But no applause greeted me. My mama watched me, unimpressed, from the window of her parlour, then came out slowly to the terrace.

‘Get down at once, Beatrice,’ she said, waving Nurse forward. ‘You have been far too long. Nurse, take Miss Beatrice upstairs and change and bath her at once. All her clothes will have to be washed. She smells like a groom.’

They pulled me off my pinnacle and my father’s eyes met mine in rueful regret. Then Nurse paused in her flight towards the house.

‘Madam!’ she said, her voice shocked.

She and my mother peeled back the layers of petticoats and found my lacy flounces stained with blood at the knees. Deftly Nurse stripped them off so she could see my legs. The stitching and the stirrup-leather flaps had rubbed my knees and calves raw and they had bled.

‘Harold!’ said my mother. It was the only sign of reproach she ever permitted herself. Papa came forward and took me into his arms.

‘Why didn’t you tell me you were hurt?’ he asked, his blue eyes narrow with concern. ‘I would have carried you home in my arms, little Beatrice. Why didn’t you tell me?’

My knees burned as if stung by nettles but I managed a smile.

‘I wanted to ride, Papa,’ I said. ‘And I want to go riding again.’

His eyes sparkled and his deep, happy laugh shouted out.

‘That’s my girl!’ he said in delight. ‘Want to go riding again, eh? Well, you shall. Tomorrow I shall go to Chichester and buy you a pony and you shall learn to ride at once. Riding till her knees bled at four years old, eh? That’s my girl!’

Still laughing, he led his horse around to the stable yard at the rear of the house where we could hear him shouting for a stable lad. I was left alone with Mama.

‘Miss Beatrice had better go straight to bed,’ she told Nurse, ignoring my wide-awake face. ‘She will be tired. She has done more than enough for one day. And she will not go riding again.’

Of course I went riding again. My mother was bound by all sorts of beliefs in vifely obedience and deference to the head of the household, and she never stood against my father for more than one self-forgetful second. A few days after my ride on the hunter and, alas, before the little scabs on the inside of my knees had healed, we heard a clatter of hoofs on the gravel and a ‘Holloa!’ from outside the front door.

On the gravel sweep outside the house stood my father’s hunter with Father astride. He was leaning down to lead the tiniest pony I had ever seen. One of the new Dartmoor breed, with a coat as dark and smooth as brown velvet and a sweep of black mane covering her small face. In a second my arms were round her neck and I was whispering into her ear.

Only one day later and Nurse had cobbled together a tiny version of a tailored riding habit for me to wear for my daily lesson with Papa in the paddock. Never having taught anyone to ride, he taught me as he had learned from his father. Round and round the water-meadows so my falls were cushioned by the soft earth. Tumble after tumble I took into the wet grass – and I did not always come up smiling. But Papa, my wonderful, godlike papa, was patient, and Minnie, dear little Minnie, was sweet natured and gentle. And I was a born fighter.

Only two weeks later, and I rode out daily with Papa. Minnie was on a leading rein and beside the hunter she looked like a plump minnow on the end of a very long line.

A few weeks after those first expeditions and Papa released me from the apprenticeship of the leading rein and let me ride alone. ‘I’d trust her anywhere,’ he said briefly to Mama’s murmured expostulations. ‘She can learn embroidery any time. She’d better learn to have a seat on a horse while she’s young.’

So Papa’s great hunter strode ahead and Minnie bobbed behind in a rapid trot to keep up. In the lanes and fields of Wideacre, the Squire and the little Mistress became a familiar sight as our rides lengthened from the original half an hour to the whole of the afternoon. Then it became part of the routine of the day that I should go out morning and afternoon with Papa. In the summer of 1760 – an especially dry hot summer – I was out every day with the Squire, and I was all of five.

These were the golden years of my childhood and even at that age I knew it. My brother Harry’s baby illnesses lingered on; they feared he had inherited Mama’s weak heart. But I was as fit as a flea and never missed a day out with Papa. Harry stayed indoors almost all winter with colds and rheums and fevers, while Mama and Nurse fussed over him. Then when spring was coming and the warm winds brought the evocative smells of warming land, he was convalescent. At haymaking, when I would be out with Papa to watch them scything down the tall rippling grass in great green sweeps, Harry would be indoors with his sneezing malady which started every year at haytime. His miserable ’atchoo, ’atchoo, would go on all through the hot days of summer, so he missed harvesting, too. At the turn of the year, when Papa promised I could go fox-cubbing, Harry would be back in the nursery or, at the best, sitting by the parlour fire with his winter ailments again.

A year older than me he was taller and plumper, but no match for me. If I succeeded in teasing him into a fight, I could easily trip him up and wrestle with him until he called for Mama or Nurse. But there was much good nature in Harry’s sweet placidity and he would never blame me for his bumps and bruises. He never earned me a beating.

But he would not romp with me, or wrestle with me, or even play a gentle game of hide-and-seek with me in the bedrooms and galleries of the Hall. He really enjoyed himself only when he was sitting with Mama in the parlour and reading with her. He liked to play little tunes on the pianoforte there, or read mournful poetry aloud to her. A few hours of Harry’s life made me unaccountably ill and tired all over. One day in the quiet company of Harry and Mama made me feel as weary as a long day in the saddle riding over the downs with Papa.

When the weather was too bad for me to be allowed out, I would beg Harry to play, but we had no games in common. As I moped round the dark library room, cheered only by finding the breeding record of Papa’s hunters, Harry would pile all the cushions he could find into the window seat and make himself a little nest like a plump wood pigeon. Book in one hand, box of comfits in the other, he was immovable. If the wind suddenly ripped a gap in the thunderclouds for the sun to pour through, he would look out at the dripping garden and say: ‘It is too wet to go out, Beatrice. You will get your stockings and shoes soaked and Mama will scold you.’

So Harry stayed indoors sucking sweets, and I ran out alone through the rose garden where every leaf, dark and shiny as holly, extended a drop of rain on its luscious point for me to lick. Every dense, clustered flower had a drop like a diamond nestling among the petals and when you sniffed the sweetness, rainwater got up your nose and made it tickle. If it rained while I was roaming, I could dive for shelter in the little white latticed summerhouse in the centre of the rose garden and watch the rain splashing on the gravel paths. But more often I would take no notice at all and walk on, on and out through the streaming paddock, past the wet ponies, along the footpath through the sheltered beech wood down to the River Fenny which lay like a silver snake in the coppice at the end of the paddock.

So although we were so near in age, we were strangers for all of our childhood. And though a house with two children in it – and one of them a romp – can never be completely still, I think we were a quiet, isolated household. Papa’s marriage to Mama had been arranged with a view to wealth rather than suitability and it was obvious to us, to the servants and even to the village, that they grated on each other. She found Papa loud and vulgar. And Papa would, too often, offend her sense of propriety by donning his Sussex drawl in her parlour, by his loud, easy laugh, and by his back-slapping chumminess with every man on our land from the poorest cottager to the plumpest tenant farmer.

Mama thought her town-bred airs and graces were an example to the county but they were despised in the village. Her disdainful, mincing walk down the aisle of the parish church every Sunday was parodied and mimicked in the taproom of the Bush by every lad who fancied himself a wit.

Our procession down the aisle, with Mama’s disdainful saunter and Harry’s wide-eyed waddle, made me blush with embarrassment for my family. Only inside our high-backed pew could I relax. While Mama and Harry stuck their heads in their hands and fervently prayed, I would sit up by Papa and slip one cold hand in his pocket.

Mama would recite prayers in a toneless murmur, but my little fingers would seek and find the private magic of my papa’s pocket. His clasp knife, his handkerchief, a head of wheat or a special pebble I had given him – more potent than the bread and wine, more real than the catechism.

And after the service, when Papa and I lingered in the churchyard to learn the village news, Mama and Harry would hurry on to the carriage, impatient of the slow, drawling jokes and fearful of infections.

She tried to belong to the village, but she had no knack of free and easy speech with our people. When she asked them how they did, or when a baby was due, she sounded as if she did not really care (which was true) or as if she found their whole lives sordid and tedious (which was also true). So they mumbled like idiots, and the women twisted their aprons in their hands as they spoke, and kept their mob caps dipped low.

‘I really fail to see what you see in them,’ Mama complained languidly after one of these abortive attempts at conversation. ‘They really are positively natural.’

They were natural. Oh, not in the sense she meant: that they were half-witted. They were natural in that they did as they felt and said what they thought. Of course they became tongue-tied and awkward in her chilly presence. What could you say to a lady who sat in a carriage high above you and asked you with every appearance of boredom what you were giving your husband for dinner that night? She might ask, but she did not care. And even more amazing to them, who believed the life of Wideacre was well known throughout the length and breadth of England, was that the Squire’s lady clearly did not know she was speaking to the wife of one of Acre’s most successful poachers, and so a true answer to the question would have been: ‘One of your pheasants, ma’am.’

Papa and I knew, of course. But there are some things that cannot be told, cannot be taught. Mama and Harry lived in a world that dealt in words. They read huge boxfuls of books delivered from London booksellers and libraries. Mama wrote long criss-crossed letters that went all over England: to her sisters and brothers in Cambridge and London, and to her aunt in Bristol. Always words, words, words. Chatter, gossip, books, plays, poetry and even songs with words that had to be memorized.

Papa and I lived in a world where words were very few. We felt our necks prickle when thunder threatened haymaking and it only needed a nod between us for me to ride to one corner of the field and Papa to ride away over to the other acres to tell the men to stack what they could and be ready for the rain. We smelled rain on the air at the start of harvesting and, without speaking, would wheel our horses round to stop the sickle gangs from cutting the standing corn with the storm coming. The important things I knew were never taught. The important things I was born knowing, because I was Wideacre born and Wideacre bred.

As for the wider world, it hardly existed. Mama would hold up a letter to Papa and say: ‘Fancy …’ And Papa would merely nod and repeat: ‘Fancy.’ Unless it affected the price of corn or wool, he had no interest.

We visited some county families, of course. Papa and Mama would attend evening parties in winter, and now and then Mama would take Harry and me to visit the children of neighbouring families: the Haverings at Havering Hall, ten miles to the west, and the de Courcey family in Chichester. But the roots of our lives were deep, deep into the Wideacre earth and our lives were lived in isolation behind the Wideacre park walls.

And after a day in the saddle, or a long afternoon watching the labourers ploughing, Papa liked nothing so much as a cigar in the rose garden while the stars came out in the pearly sky and the bats swooped and twittered overhead. Then Mama would turn from the windows of the parlour with a short sigh and write long letters to London. Even my childish eyes saw her unhappiness. But the power of the Squire, and the power of the land, kept her silent.

Her loneliness showed itself only in her continual letters, and in the way her disagreements with Papa were never won nor lost, but dragged on in indecisive pain.

The riding quarrel rumbled on throughout my childhood. My mama was bound to conventional obedience to the Master’s word, but utterly free of any moral standard. Behind her respectability and her worship of the conventions she had the morality of the gutter. Without power, she had spent all her life seeking minuscule advantages in perpetual quest for the satisfaction of getting her own way in something, anything, however small.

Poor woman! She had no control of the housekeeping monies, which were submitted by butler and cook directly to Papa and paid for out of the estate accounts. She had no control over her dress allowance, which was paid direct to the Chichester dressmaker and milliner. Once a quarter she received a few pounds and shillings for spending money: for her church collection, for her charities and for the dizzy indulgence of buying a posy of flowers or a box of sweetmeats. And even that little purse was discreetly regulated by her behaviour. After a moment’s lapse when she had spoken out to Papa shortly after my birth, the allowance had magically stopped – a seven-year-old secret that still rankled enough for Mama to whisper it to me in her enduring resentment.

I listened not at all and cared less. I was for the Squire. I was Papa’s little girl, and I understood well enough that disloyal, resentful whispers like that were part of the same attack on me and my papa as her opposition to my riding. Mama was always in search of family life as it was depicted in her quarterly journals. That was the secret reason for her hatred of my father’s uncompromising loudness, his bawdiness, his untamed joy. That was why she gloried in the quiet prettiness of her fair-haired boy. And that was why she would have done anything to get me off horseback and into the parlour where young girls, all young girls, whatever their talents and dispositions, belonged.

‘Why don’t you stay at home today, Beatrice?’ she asked in her sweet plaintive voice one morning at breakfast. Papa had already eaten and gone, and my mama turned her eyes from his plate with the great knuckle bone of ham chewed clean and the scatter of crumbs from a crusty Wideacre loaf.

‘I am riding with Papa,’ I said, my words muffled by my own hearty portion of bread and ham.

‘I know that is what you planned,’ she corrected me sharply. ‘But I am asking you to stay at home today. To stay at home with me. This morning I should like to pick some flowers and you could help me to arrange them in the blue vases. This afternoon we could go for a drive. We could even visit the Haverings. You would like that. You could chatter with Celia.’

‘I am sorry, Mama,’ I said with all the finality of an indulged seven-year-old, ‘but I promised Papa I would check the sheep on the downs and I will need all day. I shall go to the west side this morning and then ride home for dinner. This afternoon I shall go to the east side and not be back till tea-time.’

Mama compressed her lips and looked down at the table. I barely noticed her rising irritation and her tone of anger and pain was a surprise to me when she burst out: ‘Beatrice, I cannot think what is wrong with you! Time and time again I ask you to spend a day, or half a day with me, and every time you have something else you would rather do. It hurts me; it distresses me to be so rebuffed. You should not even be riding alone. It is outrageous, when I have specifically asked for your company indoors.’

I gazed blankly at her, a fork of ham halfway to my mouth.

‘You look surprised, Beatrice,’ she said crossly, ‘but in any ordinary household you would not even have learned how to ride. It is only because your father is horse-mad and you are Wideacre-mad that you have such licence. But I will not tolerate it in my daughter. I will not permit it!’

That made me afraid. Mama’s overt opposition to my daily rides could mean I was returned to the conventional pursuits of a young lady. A miserable enough fate for anyone, but if I was to be kept inside when the ploughing started, or when the reaping bands were out, or at harvest time, I should be in continual torment. Then I heard my papa’s clatter in the hall and the door banged open. Mama winced at the noise and my head jerked up like a gun dog at the sound of game, to see his bright eyes and merry smile.

‘Still feeding, little piglet?’ he bellowed. ‘Late to breakfast, late to leave and late in the fields. You have to be on the west slope and back in time for dinner, remember. You’ll have to hurry.’

I hesitated and glanced at Mama. She said nothing and her eyes were downcast. I saw the game she was playing in one swift, acute second. She had put me in a position where my defiance of her would be absolute if I went now with my papa. On the other hand, my obedience and devotion could be transferred wholesale to her if I insisted on staying indoors. I was not going to be managed by such paltry parlour games. I swallowed my mouthful and cast Mama’s secrets before my father.

‘Mama says I must stay at home today,’ I said innocently. ‘What am I to do?’

I glanced from one to the other, the picture of childish obedience. I looked as if I sought only guidance, but in my heart I had staked a large gamble on my papa.

‘Beatrice is needed out on the downs today,’ he said baldly. ‘She can stay at home tomorrow. I want her to look at the flocks today before we separate them for market and there is no one else free who can ride up there and whose judgement I can rely on.’

‘Young ladies do not generally spend all day in the saddle. I am afraid for Beatrice’s health,’ Mama said.

Papa grinned. ‘Oh stuff, ma’am,’ he said rousingly. ‘She’s as lean and as fit as a racehorse. She’s never had a day’s illness in her life. Why don’t you say what you mean?’

Mama bridled. Plain speaking is not the natural voice of ladies.

‘It’s not the proper upbringing for a girl,’ she said. ‘Spending all her time talking with such rough men. Knowing all the tenants and cottagers and galloping around the countryside without a chaperone.’