Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

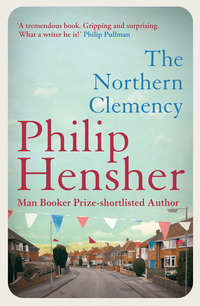

Czytaj książkę: «The Northern Clemency»

Philip Hensher

The Northern Clemency

Epigraph

what he would have done hoped to do for anyone else

E.M. FORSTER, Arctic Summer, principal fragment

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Book One

Mardy

Book Two

Nesh

Book Two-And-A-Half

In London

Book Three

Gi’ o’er

Book Four

The Giant Rat of Sumatra

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

BOOK ONE

‘So the garden of number eighty-four is nothing more than a sort of playground for all the kids of the neighbourhood?’

‘I wouldn’t say all,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘I would have said it was only the Glovers’ children.’

‘All of them?’ Mrs Warner – Karen, now – said. ‘The girl seems so quiet. It’s the elder boy, really.’

‘I’ve seen the girl going in there too,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘It’s during the day with her. She’s on her own generally. I grant you, it’s the older boy who goes in after dark, and he’s got people with him. Girls, one at a time. There’ll be trouble with both those boys.’

‘But, Mrs…’ Mr Warner said. He was slow to catch people’s names.

‘Call me Anthea,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘Now that we’ve finally met.’

‘I mean, Anthea,’ Mr Warner said, ‘why doesn’t anyone tell the parents? They surely can’t know.’

‘That I don’t understand,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. She was stately, forty-six, divorced, at number ninety-three, almost opposite the empty house. ‘This isn’t the best opportunity, I dare say.’

They were at the Glovers’. It was a party; the neighbourhood had been invited. Most had been puzzled by the invitation, knowing the couple and their three children only by sight. Mrs Arbuthnot and Mrs Warner had passed the time of day on occasion. They had arrived more or less at the same time; both had the habit, at a party, of moving swiftly to the back wall the better to watch arrivals. They had made common ground, and Mrs Warner’s husband had been introduced. He worked for the local council in a position of some authority.

It was a Friday night in August. The room was filling up, in a slightly bemused way; the neighbours, nervously boastful, were exchanging compliments about each other’s gardens; conversations about motor-cars were running their usual course.

‘It’s a nice thing for her to do,’ Mrs Warner said, who always prided herself on thinking the best of others. She had left her son, nineteen, a worry, at home; she thought the party might have been smarter than it was, not knowing the Glovers. Other people’s children had come.

‘She’s a nice woman, I believe,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said, who had her own private names for almost everyone in the room, the Warners, the Glovers included. ‘It’s a shame she couldn’t have waited a week or two, though.’

‘Yes?’ Mr Warner said, who believed that if a thing could be done today, it shouldn’t be put off until tomorrow.

‘There’s new people moving into number eighty-four,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘It might have been nice to introduce them to everyone. They’re moving in next week.’

‘Just opposite Anthea’s,’ Mrs Warner explained to her husband.

‘Perhaps it wasn’t ideal,’ Mr Warner said. ‘From the point of view of dates.’

‘People are busy in August, these days,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘They go away, don’t they?’

‘We were thinking about the Algarve,’ Mrs Warner said.

‘Oh, the Algarve,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said, encouraging and patronizing as a magazine.

It was a good party, like other parties. Mrs Glover was in a long dress: pale blue and high at the neck, it clung to her; on it were printed the names of capital cities. In vain, Mrs Warner ran her eyes over it, looking for the name of the Algarve, but it was not there.

‘Nibble?’ Mrs Glover said, frankly holding out a potato wrapped in foil, spiked with miniature assemblages of cheese and pineapple, wee cold sausages iced with fat. Her hair was swept up and pulled in, in a chignon and ringlets. They had all dressed, but she had made the most effort for her own party.

‘I so like your unit,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said.

‘We got fed up with the old sideboard,’ Mrs Glover said. ‘It was Malcolm’s mother’s, so he felt he had to take it when she went into a home. She couldn’t have all her things, naturally, so we took it, and then one day, I just looked at it and it just seemed so ugly I had to get rid of it. We got the unit from Cole’s, actually.’

‘You got it in Sheffield?’ Mrs Arbuthnot said.

‘I know,’ Mrs Glover said. ‘I saw it and I fell in love with it.’

‘It’s very nice,’ Mrs Warner said. ‘I like old things, too.’

‘I know what you mean,’ Katherine Glover said. ‘I love them, really. I just think they have so much more character than new furniture. I’d love to live in an old house.’

There was a pause.

‘But it’s original, isn’t it?’ Mr Warner said, helping her out; they seemed to be stuck on the white unit, windowed with brown smoked glass.

‘Yes,’ Katherine Glover said. She gestured around the room. ‘I think we’ve got it looking quite nice now. Finally!’

They all laughed.

‘We’ve lived here for ten years!’ she said vivaciously, as if hoping for another laugh. ‘But—’

Karen Warner remarked that it was strange how you didn’t get to meet your neighbours properly, these days.

‘This was a nice idea,’ Mr Warner said, ‘having a party like this.’ But he was wondering why, on this warm August night, the party was staying indoors and not moving out on to the patio.

There were five of them, the Glovers, in the room. Malcolm was in a suit, a borderline vivid blue, waisted and flaring about his skinny hips, flaring more modestly about the ankles, his tie a fat cushion at his neck. He carried a bottle from group to group, his smile illuminating as he moved on. ‘My wife’s idea,’ he was saying to a new couple about the party. ‘I work in the Huddersfield and Harrogate.’

‘You work in Harrogate?’ the man said. ‘That’s quite a drive every day.’

‘No,’ Malcolm said, after a heavy pause. ‘The Huddersfield and Harrogate.’

‘The building society?’ the woman said. She was a nursery nurse, pregnant herself.

‘Yes,’ Malcolm said, his puzzled voice rising. ‘Yes, the Huddersfield and Harrogate, our main offices, just off Fargate opposite the Roman Catholic cathedral. It’s women like parties, mostly. It was my wife’s idea.’

‘It was a nice idea,’ the husband said. ‘We’ve not met a lot of people in the street.’

‘We’ve admired your front garden,’ the wife said. She sneezed.

‘The idea was,’ Malcolm said, ‘that by now there’d be new people in number eighty-four. Just over there. They’d have been more than welcome.’

‘That’s a nice thought,’ the woman said, sneezing again.

‘But there must have been a hold-up,’ Malcolm said. ‘At any rate, it’s still empty.’

Elsewhere in the room, people were talking about the empty house, and about the new inhabitants.

‘Anthea Arbuthnot’s met them,’ a man was saying.

‘Oh, Anthea,’ a woman replied, and laughed. ‘What she doesn’t know isn’t worth knowing.’

‘We call her the Rayfield Avenue Clarion,’ someone’s teenage daughter said, and blushed.

‘I was saying,’ the man said, ‘Anthea Arbuthnot’s met them,’ as Mrs Arbuthnot came up, expertly balancing a pastry case filled with mushroom sauce.

‘Met who?’ Mrs Arbuthnot said.

‘The new people,’ he said. ‘Over the road.’

‘You don’t miss much,’ she said, in a not exactly unfriendly way. ‘Yes, I met them, quite by chance. The house, it’s being sold by Eadon Lockwood and Riddle, which sold me my house too, five years back. It was the same lady, which is quite a coincidence. Her name’s Mary, she breeds chocolate Labradors in her spare time, which was a little bond between us, a nice lady. I saw her coming out of the house one day with a couple as I was going down the road with Paddy, my dog, you know, and stopped to say hello. Naturally she introduced me to the people, they’d bought it by then, they were just having another look over. Measuring up for curtains and carpets, I dare say.’

The Glover girl, Jane, was at the edge of their circle, listening, her flowery print frock, her lank hair, the empty plate she had been carrying round the guests all drooping listlessly. The adults shifted politely, smiling. She was fourteen or so; just about old enough for this sort of thing. ‘Are they nice?’ she said.

Mrs Arbuthnot laughed, not at all kindly. Jane Glover just looked at her, waiting for the answer. ‘Are they nice?’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘I don’t know about that. They’re from London. He’s very London. She didn’t say anything much. They’ve got two children, nine, and a fourteen-year-old girl, I think she said.’

‘Were the children nice?’ Jane said, and now she was surely being deliberately childish.

‘They weren’t there,’ Mrs Arbuthnot said. ‘Their name – let me see – it’s on the tip of my tongue…they’re called – Mr and Mrs Sellers. That’s it.’

‘London children,’ a man said, shaking his head.

‘I hope they’re nice,’ Jane said, and then just walked away. She knew all about Mrs Arbuthnot. Under no circumstances would she tell any of these people that she, Jane, was writing a novel. Already she hated the girl, over the road, fourteen.

‘He’ll break some hearts,’ someone was saying, in another part of the room. It was Daniel Glover they were talking about. He was sixteen, lounging over the edge of the sofa, his long legs spread. His mouth hung slightly open, and from time to time he brushed away the soft fall of long black hair. Every twenty seconds the pregnant nursery nurse was sneezing, and it was Daniel she was sneezing at. His lush musk odour filled the room, making the air itch; it was the eau-de-toilette he’d lifted from Cole’s on Tuesday, and he’d practically bathed in the stuff.

Daniel looked at the party. He was thinking about sex, and he counted the women. Then he eliminated the unattractive ones, the ones over thirty-five, his mother and sister – no, he brought his sister back in just for the hell of it. Balanced it out, removed some of the men. Then – what they do, he’d read about it – the men throw their keys into a bowl, the women pick them out, then—

He lost himself in lewd speculation. Or – he started again – you could just have an orgy here. A sex orgy on the carpet. Because that happened all the time, he’d read about it. It just didn’t happen here, in this house. But he bet somewhere round here it happened all the time. Probably on this street.

Mrs Arbuthnot observed with some interest that the elder Glover boy had an erection. She enjoyed the sight: she had divorced six years ago, her long-held ambition to take part in a game of strip poker never having been fulfilled or, indeed, mentioned to anyone, least of all her ex-husband. She envisaged, like Daniel, scenes of satisfaction; for her, they were what Daniel had done, or might be doing, to the girls in the back garden of number eighty-four, watched soberly by its four dark empty windows.

‘Hay fever,’ the nursery nurse said politely, still sneezing, feeling with alarm a little dribble in her knickers.

‘They’re called Mr and Mrs Sellers,’ someone said. ‘They paid seventeen thousand for the house. Anthea Arbuthnot told me.’

Katherine Glover was relaxing, now that her party was being a success. They were eating the food; she’d made pastry cases with mushroom filling, and prawn, she’d made three different quiches, she’d made Coronation Chicken (a challenge to eat standing), she’d made assemblages of cheese-and-pineapple and cold sausages, she’d made open Danish sandwiches in tiny squares, a magazine idea, and they were eating it all. There were dishes of crisps, too, and Twiglets, but those didn’t count in the way of making an effort. They were drinking the wine, Malcolm’s choice – she’d had three glasses – and in the background, the music was exactly right, Mozart, Elvira Madigan. It was all being a great success.

The sexes were dividing now: the men were talking about their jobs, their cars, about the election, even; the women about their children’s schools, about the cost of living, and about each other.

‘Your hand’s never out of your pocket,’ one said, and another observed that her house had doubled in value in five years. One woman, worldly in manner, said that Sheffield would improve when Sainsbury’s got round to opening a branch, as she’d heard they were planning to.

‘Oh, we know Mrs Thurston,’ another said, referring to the headmistress of one of the local schools.

‘She teaches the piano, doesn’t she?’ the nursery nurse said hopefully. ‘On Charrington Road?’ She was set right, and the others started recommending piano teachers to each other, boasting about their children’s grades, merits and distinctions.

‘It’s all going to the dogs,’ a man said. ‘This’ll be a third-world country by 1980,’ and the others gravely agreed. Malcolm made his rounds again; for the last twenty minutes he had said nothing to anyone, only smiled and offered the bottle, and he was circling too soon. All the glasses were full, and the guests refused with a smile, wondering about their host, who they did not know. Absently, he offered the bottle to Daniel, who took the opportunity, his fourth, to refill his glass, still thinking of tits.

‘It would have been nice if they could have come,’ Katherine said again. ‘Sellers, they’re called.’

‘Your son’s getting to be a handsome young man,’ they said in reply.

‘I’ve got two,’ Katherine said, laughing.

‘Yes,’ they said, wondering where the other was, the one they wouldn’t have meant, since he was, what?, nine years old.

‘We invited Mrs Topsfield, too,’ she said. ‘The old lady who lives in the great big house, the old one, at the bottom of the road, the edge of the moor. But only to be polite – she wouldn’t be likely to come at her age.’

‘I’ve often wondered about her,’ someone said. ‘A gorgeous house.’

‘It’s just her in it, apparently,’ Katherine said.

‘I do think they’ve done their house beautifully,’ Karen Warner said to her husband; they had been marooned together at one side of the room. It was a handsome room; one wall had been covered with a bold paper in a bamboo print, jungle green with lemony highlights, and the others painted the palest beige. The fat suite, pushed back against the walls, and the carpet were rough oatmeal; instead of a fourth wall, a single picture window gave on to the garden.

‘It’s quite like our house, the way it’s arranged,’ Warner said.

‘Not quite, though,’ Karen said. The estate, a hundred and twenty houses, all built in one go ten years before, was elegantly varied; there were a dozen or more differently shaped houses, arranged irregularly. There was nothing municipal about the estate; but, of course, she had said this many times before. ‘Had you heard anything at work about a Sainsbury’s opening in Sheffield?’ Warner informed his wife that he had not, and that such information would not have come his way in the course of his work at the council. ‘I do like that unit,’ she said in a rush, because now she, too, had seen the elder Glover boy, sprawled about his erection.

‘I didn’t expect to be invited,’ the nursery nurse was saying, to someone she didn’t know, ‘but I’m glad I came.’ It had been ten days before; she had been resting in the afternoon, her feet, horribly swollen in this weather even at six months, up on a stool. Through the window she had seen a woman in a sleeveless summer dress stomping up the drive; a familiar figure, some sort of neighbour, with an air of imminent complaint about her walk. What now? she’d thought wearily. But the woman hadn’t rung: there was the clatter of something through the letterbox that proved, when her husband got home and picked it up, to be an invitation. ‘But who are they?’ he’d said. ‘I think we might as well go,’ she’d said, not answering his question.

But the Glovers had three children, surely: the youngest a boy, wasn’t he? Maybe he was in bed.

The youngest was behind the sofa: he had been there most of the evening, slipping behind it quite early on. Timothy had with him his favourite book in the whole world. He had been reading it steadily all evening, letting his eye run over the familiar entries. He had taken it out from the public library eleven months before; he had renewed it once, then stopped bothering. It was now ten months overdue, which caused him great terror whenever he thought of it. In happy moments, he decided that he could conceal the book where no one would find it, and his parents would never uncover the gigantic fine now building up. The fear of punishment was huge in him.

But the terror did not touch the book. It was as good now as ever. The pleasure he found in letting his eye ride over it, touching on category after category, overrode anything else. Whenever he could, he returned to its calm instructions. Even when it was not quite right of him to do so, he sensed, he found a way to be alone with it, as now burrowing behind the sofa at his parents’ party. It was so important to him that often in the last months he had found himself telling others – his best friends Simon and Ian, his sister Jane, his mother but for some reason not his brother Daniel, not his father – some facts about his subject. More oddly, he found himself asking them questions about it, as if they could instruct him, feigning ignorance, wanting to find out if they knew what he already did.

The book was about snakes. Timothy gazed at the photographs as if at a family album, committing the names he already knew to a further refreshment of memory.

He had been there for three hours, wedged between the sofa and the large picture window. If the party went outside, they would see him, and probably laugh. From time to time the back of the sofa, the porridgy tweed panels between the wood frames, bulged as someone sat down, swelling towards him, like some inchoate mass searching for him. There was a queer smell of dust down here, and the nasty smell of spilt alcohol. It was his favourite place when there was anyone in the house.

‘I don’t know where he’s got to,’ Katherine Glover said to a departing guest; it was too warm for anyone to have brought coats, but she made a helpful gesture. ‘He’s a little bit shy.’

The guest smiled; her husband made a honking noise, understanding that the woman was talking about her son, not knowing that there was any son apart from the great lout who had been lolling on the sofa, gawping at the ladies.

On the mat was an envelope, which, surely, had not been there earlier; it was addressed to Katherine, and she picked it up. In front of her, the remains of her party; the poor pregnant woman, harassed and tired, waiting for her husband to want to go. But the husband was drunk, his hair rumpled, making a hash of a joke to a group of husbands. Where was Malcolm? Sitting down, his host’s bottle in his hand, all refills at an end; and the Mozart had come to an end, too, leaving the patient silence to dismiss the guests.

‘You looked so nice,’ Jane said to her mother, coming up to her in the hall, munching a cheese straw, ‘in your posh frock and your hair like that.’

Katherine felt so terribly tired. ‘I don’t know why I bothered,’ she said crossly. ‘They didn’t appreciate it at all.’

Jane looked at her mother in astonishment. ‘It was a lovely party,’ she said. ‘You should always wear your hair like that.’

‘What, to work?’ Katherine said. ‘Don’t be daft.’

‘Thank you so much,’ the drunk man was saying, ‘for a lovely time, my dear. We’ve had a lovely, lovely time.’

He leant towards her, as if to kiss her, but did not; Katherine had him by the shoulders, a gesture that might have been affectionate, holding him at arm’s-length inspection.

‘We’ve had a very good time,’ the pregnant woman said. But it didn’t look it.

‘When is your baby due?’ Jane said abruptly.

‘In November,’ the woman said, not smiling. She took her husband by the arm, and they went.

‘Where’s your dad?’ Katherine said, but then Daniel was in the hall, up from the sofa for the first time all evening.

‘Just going out for a second,’ he muttered.

‘One second—’ Katherine said, but he was gone. ‘Oh, well.’

And then Daniel, who had answered all polite inquiries with a brief grunt and a shrug, who had not moved from his perch on the arm of the sofa, like a vast and lurid ornament, proved himself to have been all along the ringmaster of the festivities. Because with his departure the party was decisively over, and the few remaining guests moved towards the front door where Mrs Glover, her daughter at her side, was standing. In kindness, they bent and said a word to Malcolm, who said something in return, and then, with a chorus of thanks, they were out.

‘I do love your unit,’ Mrs Warner said over her shoulder, a final kindly thought disappearing into the lush August night. ‘As I was saying, I do love your…’

Goodbye, goodbye…and Katherine opened the envelope in her hand. It was an unfamiliar hand, elegant and swooping, in real ink, and the general gist of apology was clear before the signature was deciphered. She read it again, and smiled, her first genuine smile all evening.

‘Have they all gone?’ she heard Timothy saying, as he got up from behind the sofa, book in hand.

‘I think so,’ his father said, his voice muffled, regretful in the other room. ‘Where’s your brother?’

Daniel was in the street. It was half past nine. The road and the estate, in this summer twilight, had a lush warm glow; in the houses, up and down the avenue, single lights were coming on automatically, guiding the couples home from the party; husbands and wives, arm in arm and in the summer gloaming turned into lovers. The thin trees, planted ten years before, had lost their daylit lack of conviction and formed a delicate orchard, marking the edges of the quiet street. The night was perfumed, and Daniel, perfumed too, sniffed it all up.

Barbara was there, waiting for him. He had told her to wait on the wall outside number eighty-four. It was less suspicious to be casual like that rather than, as she was doing, cowering under the porch at the side of the house. Everyone knew it was empty; anyone could see her from the street. It was asking for trouble. Worse, it showed Barbara didn’t trust him, didn’t automatically think he was right. He decided to dump her after tonight, or maybe after the weekend.

‘I thought you weren’t coming,’ she said, in a burst.

‘Well, I’ve come now,’ he said, and dived for her mouth. She gave a small squeal, the beginning of a protest; but he knew to let his mouth just stay at the edge of a kiss, not forcing it, and in a second her hard teeth seemed to make way. They stayed like that for a minute; once or twice she made a pretty little noise, almost animal, and each time, not quite knowing whether he was mocking or encouraging her, he made something of the same noise back, but deeper, the sound vibrating through their twinned lips, making them buzz and ache, fulfilling the desire and stirring up more. Finally he pulled away. He looked at her critically; the little squeal, the blonde hair frizzing up in one, the pink roundness of her pinked-up face, lips and tits. Perhaps the boys had it right when they called her Crystal Tipps and laughed at him. Or maybe they were jealous. ‘I came as soon as I could,’ he said. ‘They were having a party.’

‘You said they were,’ Barbara said. ‘I don’t know why I couldn’t be allowed to come. I’d have behaved.’

‘It was boring,’ he said. ‘There was nothing but neighbours. They didn’t know each other, my mum didn’t know them. I don’t know why she asked them.’

‘We know all our neighbours,’ Barbara said with astonishment, ‘their birthdays, star signs, the lot. The telly programmes they watch, even.’

‘That’s because you live in a terraced house,’ Daniel said. ‘You could hear everything through the walls. When they fuck.’

‘Do you mind?’ Barbara said, objecting to the word rather than Daniel’s snobbery. But she drew close again, pulling him with her out of the light from the street towards the empty, overgrown garden.

‘They were all saying,’ Daniel murmured, his mouth against hers, running his tongue against her lips as they walked backwards into the lyric night, ‘they were all saying, who’s that gorgeous girl, goes into the neighbours’ gardens with Daniel Glover—’

‘They were not,’ Barbara said, her eyes bright, her hand running down Daniel’s side.

‘They were,’ Daniel said, his hand, his rippling fingers rising, weighing, cupping, down and under, beneath and within. ‘And I said—’

‘Oh, give over,’ Barbara said. But Daniel carried on, his hushed, exuberant voice now muted, and as they fell back against the lawn, which had grown into a thick meadow, she gave in to what he knew she felt. There was some indulgent amusement deep within him, and he never completely surrendered to the sensation, was never reduced to begging animal favours or further steps in the exploration of what she would grant him. His gratification, always, lay in seeing her so helpless; his pleasure in the expert and improving knack of bestowing pleasure. The noises she made were on some level comic, ‘Nnngg,’ she went, and an observation post in him kept alert over the expanding border territory between her propriety and her desire. They began when he chose to begin; they ended when he said he had to go, and when he knew that she would say disappointedly, ‘Do you have to?’

Barbara was in his maths set; he’d heard some of the things she’d been letting out about him. Flattering, really. He didn’t talk about her. Another couple of times, and that would be it; he’d seen the way Michael Cox’s sister looked at him, though she was eighteen next month. That would be something to talk about.

It was not clear to any of the Glovers what the purpose of the party had been. Not even to Katherine, whose idea it had been. He hadn’t come, after all. When the last of the guests had gone, the other two children went upstairs, Timothy holding a book. Malcolm sat down and, with his heels, dragged the armchair into a position facing the television. He did not get up to turn it.

Katherine put the letter on the shelf over the radiator, and began to go round the room, picking up glasses and plates. Malcolm had put the empty bottles in the kitchen as he had got through them. There were two open bottles left, one red and one white. The food had mostly been eaten, the tablecloth around the large oval dish of Coronation Chicken stained yellow where spoonfuls had been carelessly dropped. She began to talk as she collected the remains. She was wiping the thought that Nick, after all that effort, hadn’t come. He’d said he would.

‘They seemed to have a good time,’ she said. ‘I thought the food went well. I was worried they wouldn’t be able to eat it standing up, but people manage, don’t they?’

Malcolm said nothing. She sighed.

‘It’s a shame the new people over the road haven’t moved in yet,’ she said. ‘It would have been a good opportunity for them to meet the neighbours. Most people came, I think. There was a nice little letter from the lady in the big house, saying she was sorry she couldn’t come. She doesn’t like to go home after dark. Silly, really – it’s only a hundred yards, I don’t know what she thinks would happen to her, and it’s not really dark, even now. They get set in their ways, old people.’

Malcolm gave no sign of listening.

She couldn’t be sure what the reason for the party had been. But for her it had been defined by the people who hadn’t come rather than those who had. Not just one person; two of them. All evening she’d felt impatient with her guests who, by stooping to attend, had shown themselves to be not quite worth knowing. She projected her idea of the sort of friends she ought to have on to the new people – the Sellerses – and Mrs Topsfield, with the exquisite handwriting and supercilious reason for not attending. The Sellerses were going to be smart London people. That was absolutely clear.

‘Did you miss your battle re-creation society tonight?’ she said to Malcolm, to be kind.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t matter, once in a while.’

‘You could have invited some of them to come tonight,’ she said, although she’d rather not have to meet grown men who dressed up in Civil War uniforms and disported themselves over the moors, pretending to kill each other. It was bad enough being married to one.

‘I thought it was just for the neighbours,’ Malcolm said. ‘You said you weren’t going to invite anyone else.’

Upstairs, Jane shut her door. It was too early to go to bed, but it was accepted that she spent time in her room; homework, her mother said hopefully, but, really, Jane sat in her room reading. There were forty books on the two low shelves, and a blank notebook. She had read them all, apart from The Mayor of Casterbridge, a Christmas present from a disliked aunt; she had been told that Jane liked reading old books and that, with a life of Shelley, now lost, unread, had been the result. Jane’s books were of orphans, of love between equals, of illegitimate babies, treading round the mystery of sex and sometimes ending just before it began.

Her room was plain. Three years before she had been given the chance to choose its décor. Her mother had made the offer as the promise of a special treaty enacted between women, something to be conveyed only afterwards to the men. Jane had appreciated the tone of her mother’s confiding voice, but was baffled by the possibilities. It was that she had no real idea what role her bedroom’s décor was supposed to play in her mother’s half-angry plans for social improvement, and she was under no illusions that if she actually did choose wallpaper, curtains, paint, bedspread, carpet, even, that her choice would be measured against her mother’s unshared ideas and probably found disappointing. Would it be best to ask for an old-fashioned style, ‘with character’, as her mother said, a pink teenage girl’s bedroom? Or to opt for her own taste, whatever that might be?