Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

Copyright © Paul Preston 2014

Paul Preston asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

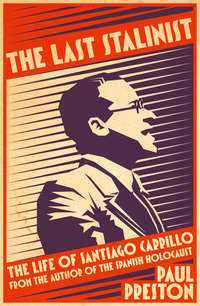

Cover by Jonathan Pelham based on a photograph © EFE/Lafototeca.com

Source ISBN: 9780007558407

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780007591824

Version: 2014-10-20

DEDICATION

In memory of Michael Jacobs

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface

Author’s Note

1 The Creation of a Revolutionary: 1915–1934

2 The Destruction of the PSOE: 1934–1939

3 A Fully Formed Stalinist: 1939–1950

4 The Elimination of the Old Guard: 1950–1960

5 The Solitary Hero: 1960–1970

6 From Public Enemy No. 1 to National Treasure: 1970–2012

Epilogue

Abbreviations

Notes

Picture Section

Illustration Credits

A Note on Primary Sources

Bibliography

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In a sense, the origins of this book date back to the 1970s when I first began to collect information about the anti-Francoist resistance. At the time and subsequently, I had long conversations with many of the protagonists of the book, including Santiago Carrillo himself. Many of those who shared their opinions and memories with me have since died. However, I would like to put on record my gratitude to them: Santiago Álvarez, Manuel Azcárate, Rafael Calvo Serer, Fernando Claudín, Tomasa Cuevas, Carlos Elvira, Irene Falcón, Ignacio Gallego, Jerónimo González Rubio, Carlos Gurméndez, Antonio Gutiérrez Díaz, K. S. Karol, Domingo Malagón, José Martinez Guerricabeitia, Miguel Núñez, Teresa Pàmies, Javier Pradera, Rossana Rossanda, Jorge Semprún, Enrique Tierno Galvan, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Francesc Vicens and Pepín Vidal Beneyto.

Over the years, I discussed the issues raised in the book with friends and colleagues who have worked on the subject, some of whom played a part in the events related therein. I am grateful for what I have learned from Beatriz Anson, Emilia Bolinches, Jordi Borja, Natalia Calamai, William Chislett, Iván Delicado, Roland Delicado, Carlos García-Alix, Dolores García Cantús, David Ginard i Féron, María Jesús González, Carmen Grimau, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Enrique Líster López, Esther López Sobrado, Aurelio Martín Nájera, Rosa Montero, Silvia Ribelles de la Vega, Michael Richards, Ana Romero, Nicolás Sartorius, Irène Tenèze, Miguel Verdú and Ángel Viñas Martín.

Finally, this book would not have been possible without the friends who helped with documentation and who read all or part of the text: Javier Alfaya, Nicolás Belmonte Martínez, Laura Díaz Herrera, Helen Graham, Susana Grau, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Michel Lefevbre, Teresa Miguel Martínez, Gregorio Morán, Linda Palfreeman, Sandra Souto Kustrin and Boris Volodarsky. I am immensely grateful to them all.

PREFACE

This is the complex story of a man of great importance. From 1939 to 1975, the Spanish Communist Party (the Partido Comunista de España, or PCE) was the most determined opponent of the Franco regime. As its effective leader for two decades, Santiago Carrillo was arguably the dictator’s most consistent left-wing enemy. Whether Franco was concerned about the left-wing opposition is another question. However, the lack of a comparable figure in either the anarchist or Socialist movements means that the title belongs indisputably to Carrillo.

Carrillo’s was a life of markedly different and apparently contradictory phases. In the first half of his political career, in Spain and in exile, from the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s, Santiago Carrillo was admired by many on the left as a revolutionary and a pillar of the anti-Franco struggle and hated by others as a Stalinist gravedigger of the revolution. For many on the right, he was a monster to be vilified as a mass murderer for his activities during the Civil War. He came to prominence as a hot-headed leader of the Socialist Youth whose incendiary rhetoric contributed in no small measure to the revolutionary events of October 1934. After sixteen months in prison, he abandoned, and betrayed, the Socialist Party by taking its youth movement into the Communist Party. This ‘dowry’ and his unquestioning loyalty to Moscow were rewarded during the Civil War by rapid promotion within the Communist ranks. Not yet twenty-two years old, he became public order chief in the besieged Spanish capital and acquired enduring notoriety for his alleged role in the episodes known collectively as Paracuellos, the elimination of right-wing prisoners. After the war, he was a faithful apparatchik, who by dint of skill and ruthless ambition rose to the leadership of the Communist Party.

Then, in the course of the second half of his political career, from the mid-1970s until his death in 2012, he came to be seen as a national treasure because of his contribution to the restoration of democracy. From his return to Spain in 1976 until 1981, his skills, honed in the internal power struggles of the PCE, were applied in the national political arena. During the early years of the transition, it appeared as if the interests of the PCE coincided with those of the population. He would be canonized as a crucial pillar of Spanish democracy as a result of his moderation then. He was particularly lauded for his bravery on the night of 23 February 1981 when the Spanish parliament was seized as part of a failed military coup. After that time, his role reverted to that of Party leader and he was undone by generational conflict. Between 1981 and 1985, he presided over the destruction of the Communist Party, which he had spent forty years shaping in his own image. Accordingly, in later life and on his death, he was the object of many tributes and accolades from members of the Spanish establishment ranging from the King to right-wing heavyweights.

The chequered nature of Carrillo’s political career poses the question of whether he was simply a cynical and clever chameleon. In 1974, denying the existence of a personality cult within the PCE, he proclaimed: ‘I will never permit propaganda being made about myself.’1 Then, in an interview given two years later, he announced: ‘I will never write my memoirs because a politician cannot tell the truth.’2 He had already contradicted the first of these denials by dint of speeches and internal Party reports in which he constructed the myth of a selfless fighter for democracy. Then, in his last four decades, he propagated numerous accounts of his life in countless interviews, in more than ten of the many books that he wrote himself and in two others that he dictated.3 In this regard, he shared with Franco a dedication to the constant rewriting and improving of his own life story.

Accordingly, this account of a fascinating life differs significantly from the many versions produced by the man himself which are contrasted here with copious documentation and the interpretations of friends and enemies. There can be little here about Carrillo’s personal life. From the time that he entered employment at the printing works of the Socialist Party aged thirteen until his retirement from active politics in 1991, he seems not to have had much of one. Certainly, his life was dominated by his political activity, but he surrounded accounts about his existence outside politics with a web of contradictory statements and downright untruth.4 Despite his apparent gregariousness and loquacity, this is the story of a solitary man. One by one he turned on those who helped him: Largo Caballero, his father Wenceslao Carrillo, Segundo Serrano Poncela, Francisco Antón, Fernando Claudín, Jorge Semprún, Pilar Brabo, Manuel Azcárate, Ignacio Gallego – the list is very long. In his anxiety for advancement, he was always ready to betray or denounce comrades. Such ruthlessness was another characteristic that he shared with Franco. What will become clear is that Carrillo had certain qualities in abundance – a capacity for hard work, stamina and endurance, writing and oratorical skills, intelligence and cunning. Unfortunately, what will become equally clear is that honesty and loyalty were not among them.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Although I hope the context always makes the meaning clear, I have used the word ‘guerrilla’ in its original Spanish meaning.

The Spanish word does not mean, as in English usage, ‘a guerrilla fighter’, but rather something closer to ‘campaign of guerrilla warfare’. See here: ‘On 20 September, Pasionaria herself had published a declaration hailing the guerrilla as the way to spark an uprising in Spain.’ For the guerrilla fighters themselves, I have used the singular guerrillero or the plural guerrilleros.

1

The Creation of a Revolutionary: 1915–1934

Santiago Carrillo was born on 18 January 1915 to a working-class family in Gijón on Spain’s northern coast. His grandfather, his father and his uncles all earned their living as metalworkers in the Orueta factory. Prior to her marriage, his mother, Rosalía Solares, was a seamstress. His father Wenceslao Carrillo was a prominent trade unionist and member of the Socialist Party who made every effort to help his son follow in his footsteps. As secretary of the Asturian metalworkers’ union, Wenceslao had been imprisoned after the revolutionary strike of August 1917. Indeed, Santiago claimed later that his most profound memory of his father was seeing him regularly being taken away by Civil Guards from the family home. It was there, and later in Madrid, that he grew up within a warm and affectionate extended family in an atmosphere soaked in a sense of the class struggle. Such a childhood would help account for the impregnable self-confidence that was always to underlie his career. He asserted in his memoirs that family was always tremendously important to him.1 That, however, would not account for the viciousness with which he renounced in father in 1939. Then, as throughout his life, at least until his withdrawal from the Communist Party in the mid-1980s, political loyalties and ambition would count for far more than family.

Santiago was one of seven children, two of whom died very young. His brother Roberto died during a smallpox epidemic in Gijón that Santiago managed to survive unscathed thanks to the efforts of his paternal grandmother, who slept in the same bed to stop him scratching his spots. A younger sister, Marguerita, died of meningitis only two months after being born. A brother born subsequently was also named Roberto. Coming from a left-wing family, Santiago was not short of rebellious tendencies and, perhaps inevitably, they were exacerbated when he attended Catholic primary school. By then the family had moved to Avilés, 12 miles west of Gijón. For an inadvertent blasphemy, he was obliged to spend an hour kneeling with his arms stretched out in the form of a cross while holding extremely heavy books in each hand. In reaction to the bigotry of his teachers, his parents took him out of the school. Shortly afterwards, the local workers’ centre opened, in the attic of its headquarters, a small school for the children of trade union members. A non-religious teacher was difficult to find and the task fell to a hunchbacked municipal street-sweeper who happened to be slightly more cultured than most of his comrades. Carrillo later remembered with regret the cruel mockery to which he and his fellow urchins subjected the poor man.

Not long afterwards, in early 1924, with Wenceslao now both a full-time trade union official of the General Union of Workers (Unión General de Trabajadores) and writing for El Socialista, the newspaper of the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, or PSOE), the family moved to Madrid. There, on the exiguous salary that the UGT could afford to pay Wenceslao, they lived in a variety of poor working-class districts. At first, they endured appalling conditions and Santiago later recalled that he witnessed suicides and crimes of passion. In the barrio of Cuatro Caminos, he had the good luck to gain entry to an excellent school, the Grupo Escolar Cervantes.2 He later attributed to its committed teachers and its twelve-hour school-day enormous influence in his development, in particular his indubitable work ethic. Whatever criticisms might be made of Carrillo, an accusation of laziness would never be one of them. He was also toughened up by the constant fist-fights with a variety of school bullies.

As a thirteen-year-old his ambition was to be an engineer. However, neither the school nor his family could afford the cost of the examination entry fee for each of the six subjects of the school-leaving certificate. Accordingly, without being able to pursue further studies, he left school with a burning sense of social injustice. Thanks to his father, he would soon embark on a meteoric rise within the Socialist movement. Wenceslao managed to get him a job at the printing works of El Socialista (la Gráfica Socialista). This required him to join the UGT and the Socialist youth movement (Federación de Juventudes Socialistas). As early as November 1929, the ambitious young Santiago, not yet fifteen years of age, published his first articles in Aurora Social of Oviedo, calling for the creation of a student section of the FJS. Helped by the position of his father, he enjoyed a remarkably rapid rise within the FJS, almost immediately being voted on to its executive committee. Of key importance in this respect was the patronage that derived from Wenceslao Carrillo’s close friendship with the hugely influential union leader Francisco Largo Caballero. An austere figure in public life, Largo Caballero was affectionately known as ‘Don Paco’ in the Carrillo household.

The two families used to meet socially for weekly picnics in Dehesa de la Villa, a park outside Madrid. Along with the food and wine, they used to bring a small barrel-organ (organillo). It was used to accompany Don Paco and his wife Concha as they showed off their skill in the typical Madrid dance, the chotis. This family connection was to constitute a massive boost to Santiago’s career within the PSOE. Indeed, the veteran leader had often given the baby Santiago his bottle and felt a paternalistic affection for him that would persist until the Civil War. Later, when he was old enough to understand, Santiago would avidly listen to the conversations of his father and Largo Caballero about the internal disputes within both the UGT and PSOE. There can be little doubt that the utterly pragmatic, and hardly ideological, stances of these two hardened union bureaucrats were to be a deep influence on Santiago’s own political development. Their tendency to personalize union conflicts would also be reflected in his own later conduct of polemics in both the Socialist and Communist parties.3

Santiago was soon publishing regularly in Renovación, the weekly news-sheet of the FJS. This brought him into frequent contact with his almost exact contemporary, the famous intellectual prodigy Hildegart Rodríguez, who as a teenager was already giving lectures and writing articles on sexual politics and eugenics. She spoke six languages by the age of eight and would have a law degree at the age of seventeen. Just as she was rising to prominence within the Socialist Youth, she was shot dead by her mother, Aurora, jealous of Hildegart’s growing independence.

In early 1930, the editor of El Socialista, Andrés Saborit, offered Santiago the chance to leave the machinery of the printing works and work full time in the paper’s editorial offices. It was a promotion that suggested the hands of his father and Don Paco. He started off modestly enough, cutting and pasting agency items and then writing headlines for them. However, he was soon a cub journalist and given the town-hall beat.4

The end of January 1930 saw the departure of the military dictator General Miguel Primo de Rivera. Between then and the establishment of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931, there was intense ferment within the Socialist movement. Certainly, there were as yet few signs of the radicalization that would develop after 1933 and catapult Santiago Carrillo into prominence on the left. The issues in those early days of the Republic revolved around the validity and value of Socialist collaboration with government. In the late 1920s, just as Santiago Carrillo was becoming involved in the Socialist Youth, there were basically three factions within both the Unión General de Trabajadores and the Socialist Party. The most moderate of the three was the group led by the academic Julián Besteiro, president since 1926 of both the party and the union and Professor of Logic at the University of Madrid.5 In the centre, at this stage the most realistic although paradoxically, in the context of the time, the most radical, was the group associated with Indalecio Prieto, the owner of the influential Bilbao newspaper El Liberal.6 The third, and the one to which Carrillo’s father Wenceslao was linked, was that of Largo Caballero, who was vice-president of the PSOE and secretary general of the UGT.7 Given his junior position on the editorial staff of El Socialista, which brought him into daily contact with Besteiro’s closest collaborator, Andrés Saborit, and given his links to Largo Caballero via his father, Santiago Carrillo found it easy to follow the internal polemics even if, to protect his job, he did not yet publicly take sides.

Although extremely conservative, Besteiro seemed to be the most extremist of the three leaders because of his rigid adherence to Marxist theory. The Spanish Socialist movement was essentially reformist and had, with the exception of Besteiro, little tradition of theoretical Marxism. In that sense, it was true to its late nineteenth-century origins among the working-class aristocracy of Madrid printers. Its founder, the austere Pablo Iglesias Posse, was always more concerned with cleaning up politics than with the class struggle. Julián Besteiro, his eventual successor as party leader, also felt that a highly moral political isolationism was the only viable option in the corrupt political system of the constitutional monarchy. In contrast, and altogether more realistically, Indalecio Prieto, who was unusual in that he did not have a trade union behind him, believed that the Socialist movement should do whatever was necessary to defend workers’ interests. His experiences in Bilbao politics had convinced him of the prior need for the establishment of liberal democracy. His early electoral alliances with local middle-class Republicans there led to him advocating a Republican–Socialist coalition as a step to gaining power.8 This had brought him into conflict with Largo Caballero, who distrusted bourgeois politics and believed that the proper role of the workers’ movement was strike action. The lifelong hostility of Largo Caballero towards Prieto would eventually be assumed by Santiago Carrillo and, from 1934, become part of his political make-up.

In fact, the underlying conflict between Prieto and Largo Caballero had been of little consequence before 1914. That was largely because in the two decades before the boom prompted by the Great War, prices and wages remained relatively stable in Spain – albeit they were among the highest prices and lowest wages in Europe. As a result, there was little meaningful debate in the Socialist Party over whether to attain power by electoral means or by revolutionary strike action. In 1914, those circumstances began to change. As a non-belligerent, Spain was able to supply food, uniforms, military equipment and shipping to both sides. A frenetic and vertiginous industrial boom accompanied by a fierce inflation reached its peak in 1916. In response to a dramatic deterioration of social conditions, the PSOE and the UGT took part in a national general strike in mid-August 1917. Even then, the maximum ambitions of the Socialists were anything but revolutionary, concerned rather to put an end to political corruption and government inability to deal with inflation. The strike was aimed at supporting a broad-based movement for the establishment of a provisional government that would hold elections for a constituent Cortes to decide on the future form of state. Despite its pacific character, the strike that broke out on 10 August 1917 was easily crushed by savage military repression in Asturias and the Basque Country, two of the Socialists’ three major strongholds – the third being Madrid. In Asturias, the home province of the Carrillo family, the Military Governor General Ricardo Burguete y Lana declared martial law on 13 August. He accused the strike organizers of being the paid agents of foreign powers. Announcing that he would hunt down the strikers ‘like wild beasts’, he sent columns of regular troops and Civil Guards into the mining valleys where they unleashed an orgy of rape, looting, beatings and torture. With 80 dead, 150 wounded and 2,000 arrested, the failure of the strike was guaranteed.9 Manuel Llaneza, the moderate leader of the Asturian mineworkers’ union, referring to the brutality of the Spanish colonial army in Morocco, wrote at the time of the ‘African hatred’ during an action in which one of Burguete’s columns was under the command of the young Major Francisco Franco.10 As a senior trade unionist who took part in the strike and had experienced the severity of the consequent repression in Asturias, Wenceslao Carrillo was notable thereafter for his caution in any decision that could lead the Socialist movement into perilous conflict with the state apparatus.

The four-man national strike committee was arrested in Madrid. It consisted of the PSOE vice-president, Besteiro, the UGT vice-president, Largo Caballero, Andrés Saborit, leader of the printers’ union and already editor of El Socialista, and Daniel Anguiano, secretary general of the Railway Workers’ Union (Sindicato Ferroviario Nacional). Very nearly condemned to summary execution, all four were finally sentenced to life imprisonment and spent several months in jail. After a nationwide amnesty campaign, they were freed as a result of being elected to the Cortes in the general elections of 24 February 1918. The entire experience was to have a dramatic effect on the subsequent trajectories of all four. In general, the Socialist leadership, particularly the UGT bureaucracy, was traumatized, seeing the movement’s role in 1917 as senseless adventurism. Largo Caballero, like Wenceslao Carrillo, was more concerned with the immediate material welfare of the UGT than with possible future revolutionary goals. He was determined never again to risk existing legislative gains and the movement’s property in a direct confrontation with the state. Both Besteiro and Saborit also became progressively less radical. In different ways, all three perceived the futility of Spain’s weak Socialist movement undertaking a frontal assault on the state. Anguiano, in contrast, moved to more radical positions and was eventually to be one of the founders of the Communist Party.

In the wake of the Russian revolution, continuing inflation and the rising unemployment of the post-1918 depression fostered a revolutionary group within the Socialist movement, particularly in Asturias and the Basque Country. Anguiano and others saw the events in Russia and the failure of the 1917 strike as evidence that it was pointless to work towards a bourgeois democratic stage on the road to socialism. Between 1919 and 1921, the Socialist movement was to be divided by a bitter three-year debate on the PSOE’s relationship with the Communist International (Comintern) recently founded in Moscow. The fundamental issue being worked out was whether the Spanish Socialist movement was to be legalist and reformist or violent and revolutionary. The pro-Bolshevik tendency was defeated in a series of three party congresses held in December 1919, June 1920 and April 1921. In a closely fought struggle, the PSOE leadership won by relying on the votes of the strong UGT bureaucracy of paid permanent officials. The pro-Russian elements left to form the Spanish Communist Party.11 Numerically, this was not a serious loss but, at a time of grave economic and social crisis, it consolidated the fundamental moderation of the Socialist movement and left it without a clear sense of direction.

Indalecio Prieto had become a member of the PSOE’s executive committee in 1918.12 He represented a significant section of the movement committed to seeking reform through the electoral victory of a broad front of democratic forces. He was appalled when the paralysis within the Socialist movement was exposed by the coming of the military dictatorship of General Primo de Rivera on 13 September 1923. The army’s seizure of power was essentially a response to the urban and rural unrest of the previous six years. Yet the Socialist leadership neither foresaw the coup nor showed great concern when the new regime began to persecute other workers’ organizations. A joint PSOE–UGT note simply instructed their members to undertake no strikes or other ‘sterile’ acts of resistance without instructions from their two executive committees lest they provoke repression. This reflected the determination of both Besteiro and Largo Caballero never again to risk the existence of the UGT in direct confrontation with the state, especially if doing so merely benefited the cause of bourgeois liberalism.13

It soon became apparent that it would be a short step from avoidance of risky confrontation with the dictatorship to active collaboration. In view of the Socialist passivity during his coup, the dictator was confident of a sympathetic response when he proposed that the movement cooperate with his regime. In a manifesto of 29 September 1923, Primo thanked the working class for its attitude during his seizure of power. This was clearly directed at the Socialists. It both suggested that the regime would foster the social legislation longed for by Largo Caballero and the reformists of the UGT and called upon workers to leave those organizations which led them ‘along paths of ruin’. This unmistakable reference to the revolutionary anarcho-syndicalist CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) and the Spanish Communist Party was a cunning and scarcely veiled suggestion to the UGT that it could become Spain’s only working-class organization. In return for collaborating with the regime, the UGT would have a monopoly of trade union activities and be in a position to attract the rank and file of its anarchist and Communist rivals. Largo Caballero was delighted, given his hostility to any enterprise, such as the revolutionary activities of Communists and anarchists, that might endanger the material conditions of the UGT members. He believed that under the dictatorship, although the political struggle might be suspended, the defence of workers’ rights should go on by all possible means. Thus he was entirely open to Primo’s suggestion.14 In early October, a joint meeting of the PSOE and UGT executive committees agreed to collaborate with the regime. There were only three votes against the resolution, among them those of Fernando de los Ríos, a distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Granada, and Indalecio Prieto, who argued that the PSOE should join the democratic opposition against the dictatorship.15

Besteiro, like Largo Caballero, supported collaboration, albeit for somewhat different reasons. His logic was crudely Marxist. From the erroneous premise that Spain was still a semi-feudal country awaiting a bourgeois revolution, he reasoned that it was not the job of the Spanish working class to do the job of the bourgeoisie. In the meantime, however, until the bourgeoisie completed its historic task, the UGT should seize the opportunity offered by the dictatorship to have a monopoly of state labour affairs. His argument was built on shaky foundations. Although Spain had not experienced a political democratic revolution comparable to those in England and in France, the remnants of feudalism had been whittled away throughout the nineteenth century as the country underwent a profound legal and economic revolution. Besteiro’s contention that the working class should stand aside and leave the task of building democracy to the bourgeoisie was thus entirely unrealistic since the landowning and financial bourgeoisie had already achieved its goals without a democratic revolution. His error would lead to his ideological annihilation at the hands of extreme leftist Socialists, including Santiago Carrillo, in the 1930s.