Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Saboteur»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

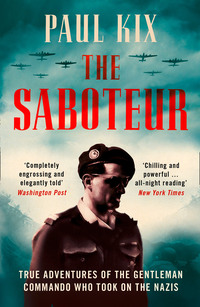

Copyright © Paul Kix 2017

Design and illustration by Leo Nickolls

Paul Kix asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007553808

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780007553815

Version: 2018-11-28

Dedication

For Sonya, as always

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

About the Author

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is a work of narrative nonfiction, meant to relay what it was like for Robert de La Rochefoucauld to fight the Nazis from occupied France as a special operative and résistant. I relied on a few primary sources to tell this story, most notably La Rochefoucauld’s memoir, La Liberté, C’est Mon Plaisir: 1940–1946, published in 2002, a decade before his death. La Rochefoucauld’s family, ever gracious, also gave me a copy of the audio recording in which Robert recounted his war and life for his children and grandchildren. This was great source material, as was a DVD I received, which was directed, edited, and produced by one of Robert’s nephews, and which tells the tale of his storied family, specifically his parents, his nine brothers and sisters, and the courage that Robert himself needed to fight his war. The DVD, like the audio recording, was made for the La Rochefoucauld family to share with successive generations, but Robert’s daughter Constance was kind enough to make me a copy.

I spoke with her and her three siblings at length about their father—in person, over Skype, on the telephone, and by email. I kept contacting them long after I said I would, and kept apologizing for it. But Astrid, Constance, Hortense, and Jean were always amenable and happy to share what they knew. I’m eternally grateful.

This narrative is the result of four years of work, with research and reporting conducted in five countries. I talked with dozens of people, read roughly fifty books, in English and French, and parsed thousands of pages of military and historical documents, in four languages. Despite all this, and no doubt because of the secret nature of La Rochefoucauld’s work, there are certain instances where Robert’s account of what happened is the best and sometimes only account of what happened. Thankfully, in those spots, Robert’s recollections are vivid and reflect the larger historical record of the region and time.

PAUL KIX, JANUARY 2017

PROLOGUE

His family kept asking him why. Why would a hero of the war align himself with one of its alleged traitors? Why would Robert de La Rochefoucauld, a man who had been knighted in France’s Legion of Honor, risk sullying his name to defend someone like Maurice Papon, who had been charged, these many decades after World War II, with helping the Germans during the Occupation?

The question trailed La Rochefoucauld all the way to the witness stand, on a February afternoon in 1998, four months into a criminal trial that would last six, and become the longest in French history.

When he entered the courtroom, La Rochefoucauld looked debonair. His silver hair had just begun to recede, and he still swept it straight back. At seventy-four, he carried the dignified air of middle age. He had brown eyes that took in the world with an ironic slant, the mark of his aristocratic forebears, and a Roman, ruling-class nose. His posture was tall and upright as he walked to the stand and gave his oath and, lowering himself to his seat at the center of international attention, he appeared remarkably relaxed—his complexion even had a bronze tint, despite the bleak French winter. He remained a handsome man, nearly as handsome as he’d been in those first postwar years, when he’d moved from one girl to the next, until he’d met Bernadette de Marcieu de Gontaut-Biron, his wife and mother of his four children.

On the stand, La Rochefoucauld wore a green tweed check jacket over a light blue shirt and a patterned brown tie. The outfit suited the country squire, who’d traveled to Bordeaux today from Pont Chevron, his thirty-room chateau overlooking sixty-six acres in the Loiret department of north-central France. He radiated a charisma that burned all the brighter when set against the gray sobriety of the courthouse. La Rochefoucauld looked better than anyone in the room.

A reputation for bravery preceded him, and almost out of curiosity for why someone like La Rochefoucauld would defend someone like Papon, the court allowed him an opening statement. La Rochefoucauld nodded at the defendant, who sat in a dark suit behind bulletproof glass. The makings of wry exasperation curled La Rochefoucauld’s lips as he recalled events from fifty years earlier.

“First, I would like to say that in 1940, although I was very young, I was against the Germans, against Pétain and against Vichy. I was in favor of the continuation of the war in the South of France and in North Africa.” He was sixteen then, and came from a family that despised the Germans. His father, Olivier, a decorated World War I officer who’d re-enlisted in 1939, was arrested by the Nazis five days after the Armistice in part because he’d tried to fight beyond the agreed-to peace. His mother, Consuelo, who ran a local chapter of the Red Cross, was known to German officers as the Terrible Countess. On the stand, La Rochefoucauld skipped over almost all of what happened after 1940, the acts of bravery that had earned him four war medals and a knighthood. He instead focused his testimony on one episode in the summer of 1944 and experiences that greatly compromised the allegations against Papon.

Maurice Papon had been an administrator within the German-collaborating Vichy government. He rose to a position of authority in the Gironde department of southwestern France, whose jurisdiction included Bordeaux. The charge against Papon was that from his post as general secretary of the Gironde prefecture, overseeing Jewish affairs, he signed deportation papers for eight of the ten convoys of Jewish civilians that left for internment camps in France, and ultimately the concentration camps of Eastern Europe. In total, Vichy officials in the Gironde shipped out 1,690 Jews, 223 of them children. Papon had been indicted for crimes against humanity.

The reality of Papon’s service was far messier than the picture the prosecutors depicted. Despite Papon’s lofty title, he was a local administrator within Vichy and so removed from authority that he later claimed he didn’t know the final destination of the cattle cars or the fate that awaited Jews there. Furthermore, Vichy’s national police chief, René Bousquet, was the person who had actually issued the deportations. Papon claimed that he had merely done as he was told, that he was a bureaucrat with the misfortune of literally signing off on orders. When the trial opened in the fall of 1997, the historian who first unearthed the papers that held Papon’s signatures, Michel Bergès, told the court he no longer believed the documents proved Papon’s guilt. Even two attorneys for the victims’ families felt “queasiness” about prosecuting the man.

Robert de La Rochefoucauld (pronounced Roash-foo-coe) knew something that would further undercut the state’s case against Papon. As he told the court, in the summer of 1944, he joined a band of Resistance fighters who called their group Charly. “There was a Jewish community there,” La Rochefoucauld testified, “and when I saw how many of them there were, I asked them what was the reason for them being part of this [group]. The commander’s answer was very simple: … ‘They had been warned by the prefecture that there would be a rounding up.’” In other words, these Jewish men were grateful they had been tipped off and happy to fight in the Resistance.

In the 1960s, La Rochefoucauld met and grew friendly with Papon, who was by then Paris’ prefect of police. “I learned he was at the [Gironde] prefecture during the war,” Robert testified. “It was then that I told him the story of the Jews of [Charly]. He smiled and said, ‘We were very well organized at the prefecture.’” Despite La Rochefoucauld’s own heroics, he said on the stand it took “monstrous reserves of personal courage” to work for the Resistance within Vichy. “I consider Mr. Papon one of those brave men.”

His testimony lasted fifteen minutes, and following it one of the judges read written statements from four other résistants, whose sentiments echoed La Rochefoucauld’s: If Papon had signed the deportation documents, he had also helped Jews elude imprisonment. Roger-Samuel Bloch, a Jewish résistant from Bordeaux, wrote that from November 1943 to June 1944, Papon hid and lodged him several times, at considerable risk to his career and life.

The court recessed until the next morning. La Rochefoucauld walked outside and took in a Bordeaux that was so very different from 1944, where no swastika flags swayed in the breeze, where no people wondered who would betray them, where no one listened for the hard tap of Gestapo boots coming up behind. How to relay in fifteen minutes the anxiety and fear that once clung to a man as surely as the wisps of cigarette smoke in a crowded café? How to explain the complexity of life under Occupation to generations of free people who would never experience the war’s exhausting calculations and would therefore view it in simple terms of good and evil? La Rochefoucauld was beyond the gated entryway of the courthouse when he saw Papon protesters move toward him. One of them got very close, and spit on him. La Rochefoucauld stared at the young man, furious, but kept walking.

What people younger than him could not understand—and this included his adult children and nieces and nephews—was that his motivation for testifying wasn’t really even about Papon, a man he hadn’t known during the war. La Rochefoucauld took the stand instead out of a fealty for the brotherhood, the tiny bands of résistants who had fought the mighty Nazi Occupation. They knew the personal deprivations, and they saw the extremes of barbarity. A silent understanding still passed between these rebels who had endured and prevailed as La Rochefoucauld had. A shared loyalty still bound them. And no allegation, not even one as grave as crimes against humanity, could sever that tie.

La Rochefoucauld hadn’t said any of this, of course, because he seldom said anything about his service. Even when other veterans had alluded to his exploits at commemorative parties over the years, he’d stayed quiet. He was humble, but it also pained him to dredge it all up again. So his four children and nieces and nephews gathered the snippets they’d overheard of La Rochefoucauld’s famous war, and they’d discussed them throughout their childhood and well into adulthood: Had he really met Hitler once, only to later slink across German lines dressed as a nun? Had he really escaped a firing squad or killed a man with his bare hands? Had he really trained with a secret force of British agents that changed the course of the war? For most of his adult life, La Rochefoucauld remained, even to family, a man unknown.

Now, La Rochefoucauld got in his Citroën and began the five-hour drive back to Pont Chevron. Maybe one day he would tell the whole story of why he had defended someone like Papon, which was really a story of what he’d seen during the war and why he’d fought when so few had.

Maybe one day, he told himself. But not today.

CHAPTER 1

One cannot answer for his courage if he has never been in danger.

—François de La Rochefoucauld, Maxims

On May 16, 1940, a strange sound came from the east. Robert de La Rochefoucauld was at home with his siblings when he heard it: a low buzz that grew louder by the moment until it was a persistent and menacing drone. He moved to one of the floor-to-ceiling windows of the family chateau, called Villeneuve, set on thirty-five acres just outside Soissons, an hour and a half northeast of Paris. On the horizon, Robert saw what he had long dreaded.

It was a fleet of aircraft, ominous and unending. The planes already shadowed Soissons’ town square, and the smaller ones now broke from the formation. These were the German Stukas, the two-seater single-engine planes with arched wings that looked to Robert as predatory as they in fact were. They dove out of the sky, the sirens underneath them whining a high-pitched wail. The sight and sound paralyzed the family, which gathered round the windows. Then the bombs dropped: indiscriminately and catastrophically, over Soissons and ever closer to the chateau. Huge plumes of dirt and sod and splintered wood shot up wherever the bombs touched down, followed by cavernous reports that were just as frightening; Robert could feel them thump against his chest. The world outside his window was suddenly loud and on fire. And amid the cacophony, he heard his mother scream: “We must go, we must go, we must go!”

World War II had come to Soissons. Though it had been declared eight months earlier, the fight had truly begun five days ago, when the Germans feinted a movement of troops in Belgium, and then broke through the Allied lines south of there, in the Ardennes, a heavily forested collection of hills in France. The Allies had thought that terrain too treacherous for a Nazi offensive—which is of course why the Germans had chosen it.

Three columns of German tanks stretching back for more than one hundred miles had emerged from the forest. And for the past few days, the French and Belgian soldiers who defended the line, many of them reservists, had lived a nightmare if they’d lived at all: attacked from the sky by Stukas and from the ground by ghastly panzers too numerous to be counted. In response, Britain’s Royal Air Force had sent out seventy-one bombers, but they were overwhelmed, and thirty-nine of the aircraft had not returned, the greatest rate of loss in any operation of comparable size in British aviation history. On the ground, the Germans soon raced through a hole thirty miles wide and fifteen miles deep. They did not head southwest to Paris, as the French military expected, but northwest to the English Channel, where they could cut off elite French and British soldiers stuck in Belgium and effectively take all of France.

Soissons stood in that northwestern trajectory. Robert and his six siblings rushed outside, where the scream of a Stuka dive was even more horrifying. Bombs fell on Soissons’ factories and the children ran to the family sedan, their mother, Consuelo, ushering them into the car. Consuelo told her eldest, Henri, then seventeen, one year older than Robert, to go to the castle at Châteaneuf-sur-Cher, the home of Consuelo’s mother, the Duchess of Maillé, some 230 miles south. Consuelo would stay behind; as the local head of the Red Cross, she had to oversee its response in the Aisne department. She would catch up with them later, she shouted at Henri and Robert. Her stony look told her eldest sons that there was no point in arguing. She was not about to lose her children, who ranged in age from seventeen to four, to the same fiery blitzkrieg that had perhaps already consumed her husband, Olivier, who—at fifty—was serving as a liaison officer for the RAF on the Franco-German border.

“Go!” she told Henri.

So the children set out, the bombs falling around them, largely unchecked by Allied planes. Though history would dub these days the Battle for France, France’s fleet was spread throughout its worldwide empire, with only 25 percent stationed in country and only one-quarter of that in operational formations. This left Soissons with minimal protection. The ceaseless screaming whine of a Stuka and deep reverberating echo of its bombs drove the La Rochefoucaulds to the roads in something like a mindless panic.

But the roads were almost at a standstill. The Germans bombed the train stations and many of the bridges in Soissons and the surrounding towns. The occasional Stuka strafed the flow of humanity, and the younger children in the La Rochefoucaulds’ car screamed with each report, but the gunfire always landed behind them.

As they inched out of the Nazis’ northwestern trajectory that afternoon, more and more Frenchmen joined the procession. Already cars were breaking down around them. Some families led horses or donkeys that carried whatever possessions they could gather and load. It was a surreal scene for Robert and the other La Rochefoucauld children, pressing their faces against the windows, a movement unlike any modern France had witnessed. The French reconnaissance pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry saw the exodus from the sky, and as he would later write in his book, Flight to Arras, “German bombers bearing down upon the villages squeezed out a whole people and sent it flowing down the highways like a black syrup … I can see from my plane the long swarming highways, that interminable syrup flowing endless to the horizon.”

Hours passed, the road stretched ahead, and though the occasional Stuka whined above, the La Rochefoucaulds were not harmed by them—these planes’ main concern was joining the formation heading to the Channel. News was sparse. Local officials had sometimes been the first to flee. The La Rochefoucauld children saw around them cars with mattresses tied to their roofs as protection from errant bombs. But Robert watched as those mattresses served a more natural purpose when the traffic forced people to camp on that first night, somewhere in the high plains of central France.

Makeshift shelters rose around them just off the road, and though no one heard the echo of bombs, Henri ordered his siblings to stay together as they climbed, stiff-legged, out of the car. Henri was serious and studious, the firstborn child who was also the favorite. Robert, with high cheekbones and a countenance that rounded itself into a slight pout, as if his lips were forever holding a cigarette, was the more handsome of the two, passing for something like Cary Grant’s French cousin. But he was also the wild one. He managed to attend a different boarding school nearly every year. The brothers understood that they were to watch over their younger siblings now as surrogate parents, but it was really Henri who was in charge. Robert, after all, had been the one immature enough to dangle from the parapet of the family chateau, fifty feet above the ground, or to once say shit in front of Grandmother La Rochefoucauld, for the thrill it gave his siblings.

The children gathered together, Henri and Robert, Artus and Pierre Louis, fifteen and thirteen, and their sister Yolaine, twelve. The youngest ones, Carmen and Aimery, seven and four, naturally weren’t part of their older siblings’ clique. They were not invited to play soccer with their brothers and Yolaine, and only occasionally did they swim with them in the Aisne river, which flowed around the family estate. They were already their own unit, unaware of the idiosyncrasies and dynamics of the older crew: the way Artus favored the company of his younger brother Pierre Louis to Henri and Robert’s, or the way all the boys tended to gang up on Yolaine, the lone girl, until Robert defended her, sometimes with his fists, the bad brother with the good heart.

Years later Robert would not recall how they spent that first night—on blankets that Consuelo had quickly stored into the trunk or with grass as their bedding and the night stars to comfort them. But he would remember walking among the great anxious swarm of humanity, who settled in clusters on a field that, under the moonlight, seemed to stretch to the horizon. Robert was as scared as the travelers around him. But, in the jokes the refugees told or even in their silent resolve, he felt a sense of fraternity spreading, tangible and real. He had often lived his life at a remove from this kind of experience: He was landed gentry, his lineage running through one thousand years of French history. When Robert and his family vacationed at exclusive resorts in Nice or Saint Tropez, they avoided mass transit, traveling aboard Grandmother La Rochefoucauld’s private rail car—with four sleeper cabs, a lounge and dining room. But the night air and communion of his countrymen stirred something in Robert, something similar to what his father, Olivier, had experienced twenty years earlier in the trenches of the Great War. There, among soldiers of all classes, Olivier had dropped his vestigial ties to monarchy and become, he said, a committed Republican. Tonight, looking out at the campfires and the families who laid down wherever they could, with whatever they had, Robert felt the urge to honor La France, and to defend it, even if the military couldn’t.

The children were on the road for four days. As many as eight million people fled their homes during the Battle for France, or one-fifth of the country’s population. The highways became so congested during this exodus that bicycles were the best mode of travel, as if the streets of Bombay had moved to the French countryside. Abandoning their car and walking would have been quicker for the La Rochefoucaulds, but Henri would have none of it. Thousands of parents lost track of their children during the movement south, and newspapers would fill their pages for months afterward with advertisements from families in search of the missing. The La Rochefoucaulds stayed in the car, always together, nudging ahead, taking hours just to cross the Loire River on the outskirts of southern France, on one of the few bridges the Germans hadn’t bombed.

The skies were clear of Stukas now, yet the roads remained as crowded as ever. This was a full-on panic, Robert thought, and though he wasn’t the best of students he understood its cause. It wasn’t just the invasion people saw that forced them out of their homes. It was the invasion they’d replayed for twenty years, the invasion they’d remembered.

World War I had killed 1.7 million Frenchmen, or 18 percent of those who fought, a higher proportion than any other developed country. Many battles were waged in France, and the fighting was so horrific, its damage so ubiquitous, it was as if the war had never ended. The La Rochefoucaulds’ own estate, Villeneuve, had been a battle site, captured and recaptured seventeen times, the French defending the chateau, the Germans across the Aisne river, firing. The fighting left Villeneuve in rubble, and the neighboring town of Soissons didn’t fare much better: 80 percent of it was destroyed. Even after the La Rochefoucaulds rebuilt, the foundation of the estate showed the classic pockmarks of heavy shells. The soil of Villeneuve’s thirty-five acres smoldered for seven years from all the mortar rounds. Steam rose from the earth, too hot to till. Well into the 1930s, Robert would watch as a plow stopped and a farmhand dug out a buried artillery round or hand grenade.

The 1,600-year-old cathedral in Soissons, where the La Rochefoucaulds occasionally went for Mass, carried the indentations of bullet and artillery fire, clustering here and boring into the edifice there, from its stone foundation to its mighty Gothic peaks. Storefronts all around them wore similar marks, while veterans like Robert’s father hobbled home after service. For Olivier, an ankle wound incurred in 1915 limited his ability to walk unassisted. His injury intruded into his pastimes: When he hunted game, he brought his wife, and Consuelo carried the gun until Olivier spotted the prey, which allowed him to momentarily ditch his cane and hoist the rifle to his shoulder. Olivier was lucky. Other veterans were so disfigured, they didn’t appear in public.

“Throughout my childhood, I heard people talk mostly about the Great War: my parents, my grandparents, my uncles,” Robert later said. But even as it remained a constant topic, Olivier seldom discussed its basic facts: his four years at the front, as an officer whose job was to watch artillery shells land on German positions and relay back whether the next round should be aimed higher or lower. Nor did Olivier discuss the more intimate details of the fighting, as other veterans did in memoirs: stepping on the “meat” of dead comrades in an offensive or the madness the trenches induced. Instead Olivier walked the halls of Villeneuve, in some sort of private and almost unceasing conversation with the ghosts of his past. He was a distant father, telling his children that they “must not cry—ever,” and finding solace in nature’s beauty. He had earned a law degree after the war, but spent Robert’s childhood as Villeneuve’s gentleman farmer. Olivier felt most at ease talking about the dahlias he planted. Consuelo, who’d lost two brothers to the trenches, was far more outspoken. She instructed her children that they were never to buy German-made goods and told her daughters they could not learn such an indelicate tongue. Even her job moored her to the past: As chair of the Aisne chapter of the Red Cross, Consuelo spent most of her time helping families whose lives had been upended by the war.

The La Rochefoucaulds were not unique: No one in France could look beyond his disfigured memories. The French military was itself so scarred that it did nothing in the face of Hitler’s mounting power. In 1936, the führer’s army reoccupied the Rhineland (the areas around the Rhine River in Belgium), in violation of World War I treaties, without a fight, even though France had one hundred divisions, and the Third Reich’s crippled army could send only three battalions to the Rhine. As Gen. Alfred Jodl, head of the German armed forces operational staff, later testified: “Considering the situation we were in, the French covering army could have blown us to pieces.” But despite overwhelming numerical strength, the French did nothing, and Germany retook the Rhine. Hitler never feared France again.

German military might grew, and as a new war seemed imminent, the French kept forestalling its reality, traumatized by what they’d already endured. In 1938, the French Parliament voted 537 to 75 for the Munich Agreement, which gave Hitler portions of Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, the World War I veteran and novelist Jean Giono wrote that war was pointless, and if it broke out again soldiers should desert. “There is no glory in being French,” Giono wrote. “There is only one glory: To be alive.” Léon Emery, a primary school teacher, wrote a newspaper column that may as well have been a refrain for people in the late 1930s: “Rather servitude than war.”

This frightened pacifism reigned even after the new war began. In the fall of 1939, after Britain and France declared war on Germany, William Shirer, an American journalist, took a train along a hundred-mile stretch of the Franco-German border: “The train crew told me not a shot had been fired on this front … The troops … went about their business [building fortifications] in full sight and range of each other … The Germans were hauling up guns and supplies on the railroad line, but the French did not disturb them. Queer kind of war.”

So at last, in May 1940, when the German planes screamed overhead, many Frenchmen saw not just a new style of warfare but the nightmares of the last twenty years superimposed on the wings of those Stukas. That’s why it took four days for the La Rochefoucauld children to reach their grandmother’s house: Memory heightened the terror of Hitler’s blitzkrieg. “We were lucky we weren’t on the road longer,” Robert’s younger sister Yolaine later said.

Grandmother Maillé’s estate sat high above Châteauneuf-sur-Cher, a three-winged castle whose sprawling acreage served as the town’s eponymous centerpiece. It was a stunning, almost absurdly grand home, spread across six floors and sixty rooms, featuring some thirty bedrooms, three salons, and an art gallery. The La Rochefoucauld children, accustomed to the liveried lifestyle, never tired of coming here. But on this spring day, the bliss of the reunion gave way rather quickly to a hollowed-out exhaustion. The anxious travel had depleted the children—and the grandmother who’d awaited them. Making matters worse, the radio kept reporting German gains, alarming everyone anew.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.