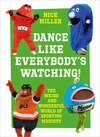

Czytaj książkę: «Dance Like Everybody’s Watching!»

Copyright

This book is not endorsed or sponsored in any way

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Jacket design by James Empringham © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019 Cover photographs: Front (clockwise from top left) © David E Klutho/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images (Big Red), Joe Robbins/Getty Images (Blue Blob), The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images (Mysterious Fish), Len Redkoles/NHLI via Getty Images (Gritty); Back (left) Thomas Starke/Bongarts/Getty Images (Stolle), (right) Etsuo Hara/Getty Images (Minamo)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Nick Miller asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008356828

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008356842

Version 2019-09-23

Dedication

TO THE MEN AND WOMEN WHO PUT ON GIANT MUPPET SUITS, WHO SWEAT UNDER SIX INCHES OF FELT WHEN IT’S 35 DEGREES, WHO ARE MAULED BY KIDS HOPPED UP ON SUGAR, WHO POSE FOR ENDLESS PHOTOS TAKEN BY FRAZZLED PARENTS, WHO GET STUFF THROWN AT THEIR HEADS AND HAVE TO BE CHEERFUL THE WHOLE TIME.

TO THE MASCOTS.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

A Brief History of Mascots

Dave Raymond – the Original

When Mascots Attack

Gareth Evans Aka Harry the Hornet

Silences

About the Publisher

Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images

INTRODUCTION

A little while ago I was at an Arsenal game. After the final whistle, as 60,000 people trudged away into the London night, I noticed a gaggle of kids and their parents gathering roughly around where the players would eventually emerge. I assumed they were waiting for pictures and autographs from their footballing heroes, but then, instead of a highly skilled and dedicated athlete, a large, green, furry dinosaur made its way out – and was mobbed.

It turns out the kids were waiting for Gunnersaurus, the friendly anthropomorphised dinosaur that, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, had been adopted as the club’s mascot some time earlier.

All of which reminded me that people think watching sport is about, well, watching sport – sitting down and paying attention only to the period of time during which these men or women run around and perform, their otherworldly talents displayed for us to enjoy, gawp and shout at, and, for a special select few, think we could do better.

But it’s not really. Well, not entirely. If that were true, nobody would talk, read, write or think about sport except for when the game was actually taking place. We wouldn’t wear implausibly expensive merchandise, we wouldn’t follow the players on social media, we would probably pay less attention to interviews with the sportsmen and women, and we would most definitely pay more attention to those better voices of our conscience who make the sadly convincing case that it is, in fact, only a game.

It is, however, the ephemera that keep us going. The things that surround sport that don’t have much to do with it. The bits that might seem superfluous but give the whole thing a little colour. The sauce on the steak; the steak is the most important bit, naturally, but you wouldn’t want it without the sauce.

Things like mascots. Those mostly furry, usually oversized, gaudy characters that prance around the field before, during and after the game, theoretically for the kids to enjoy, but more often than not for the adults to laugh at.

Because, for the most part, these mascots are absurd, surreal concoctions of a dangerous mind, bedraggled rejects from Sesame Street, characters they decided were too weird to be a sidekick to Big Bird.

We’ve had birds, dinosaurs, sheep, cows, fish, worms, tigers, lions, dogs, donkeys, ants, slugs, bats. There have been vegetables, plants, trees, chips, oranges and chillies. Some have tried fur-covered versions of people, aliens and otherworldly made-up creatures that seem to serve no purpose other than to fuel the psychotherapy industry for a generation of scarred youngsters. We’ve seen hammers, household boilers and planes. And then, the last refuge of the lazy mascot-maker, simply the relevant item of sporting equipment, with added limbs.

Essentially, if someone can figure out how to put legs and arms on something, then it can and probably has been tried as a mascot. In many cases they’re strange pieces of performance art, the sort of thing where you daren’t even think about the mental process that brought them into being.

Mascots are inherently absurd, but then again you, dear reader, almost certainly dedicate significant portions of your life to teams of men and women that have very little idea that you exist. If you support a team, given how transient the players, coaches, owners and even stadia are, you’re essentially cheering laundry, as Seinfeld once put it. And if that’s not absurd, then what is?

Which shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, fandom is just as illogical as mascots. The whole idea of mascots is based on the hope that something or someone accompanying the team might have some sort of mystical impact on how that team performs. Clearly ludicrous, but for anyone who’s had a lucky hat, shirt, jacket, socks or underwear, you know why a mascot is there.

Mascots exist as a reminder that we all take this too seriously. Sport isn’t a matter of life and death, and no, it’s not more important than that. It is, as the old saying goes, the most important of the unimportant things, but we still need a nudge every now and then to make sure we know it. What better than the sight of a deranged muppet firing T-shirts into a crowd to do that?

And in the end, whether a mascot is ill-conceived or brilliantly designed, they’re just supposed to be fun. Which is what watching sport is supposed to be.

This is a celebration of mascots. The worst, the best, the silliest, the most absurd, and everything in between. All of the examples in this book could most charitably be described as ridiculous, but the concept itself is fairly ridiculous, so why not go all-out?

Enjoy.

Adam Glanzman/Getty Images

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MASCOTS

As ever with these things, nobody is sure who or what the first mascot was, the facts lost in the mists of time.

The word ‘mascot’ itself can be traced back to medieval Latin, in which masca meant ‘mask’ or ‘nightmare’. From there it made its way into 18th-century France, where mascoto loosely translated to ‘witch’ or ‘sorcerer’. This became a slang word, mascotte, essentially referring to a lucky charm or talisman, usually associated with gambling, but the first time it was really applied to sports teams was in the 1880s in the United States.

At that stage these ‘mascots’ were usually small boys adopted by clubs, which isn’t quite as sinister as it sounds. There was a kid named Chic who is mentioned in some books; he was not connected to a specific team, but was regarded as a good-luck charm by some baseball players; the Chicago White Stockings were led in parades by a boy named Willie Hahn, who would hold their flag high; and the St. Louis Brown Stockings were associated with ‘Little Nick’, whom the Sporting Life magazine described as ‘the luckiest man in the country’, and who supposedly passed on this luck to the team. Sportspeople being inherently superstitious, the idea of anything that could bring a little extra fortune was heartily embraced.

As sports became more organised around the turn of the 20th century, mascots generally became live animals. The oldest mascot is probably Handsome Dan, a bulldog that belonged to a student at Yale in the 1890s, and stuck around: there have been 17 subsequent Dans, the name passed on down the generations of Yale bulldogs, and No. 18 is going strong at the time of writing.

Inevitably, being connected to a university, Handsome Dan has been the subject of various kidnap-related japes, the first coming in 1934 when the editors of The Harvard Lampoon abducted him ahead of a big game between the rival institutions. You had to make your own fun back then.

Over the years countless real animals have been used as mascots – horses, pigs, goats, birds, huskies, rams, bears, lions, tigers – some connected to team nicknames, some seemingly entirely random. Plenty have been paraded at games, but some – most notably the tiger and the lion – would probably be regarded as something of a health and safety concern, and are kept to the realms of the conceptual.

All of these examples are from American sports, and it would be easy to assume that the mascot was a concept born and developed in that country, something rather too gaudy for the much more prim and proper English. But it’s simply not true. Zampa the Lion, for example, Millwall’s mascot named after the road that their stadium is on, has been around for nearly a century, and not just on the club’s badge. Zampa has existed in corporeal, furry form for most of that time, at various points looking like a slightly deformed cousin of the lion from The Wizard of Oz.

England is also where we find the first mascot for a World Cup. World Cup Willie – a lion dressed in a Union Flag shirt and shorts – was designed in five minutes by an illustrator called Reg Hoye, and also came with a song by skiffle singer Lonnie Donegan. He inspired other tournaments to try their own mascots, but perhaps unsurprisingly ‘League Cup Les’, attempted a year later, didn’t quite capture the country’s imagination.

By the 1950s ‘character’ mascots started to emerge, the first probably being Mr. Oriole, mascot of the Baltimore Orioles, who emerged in around 1954 but soon faded. Not long after came one of the most famous and best loved: Mr. Met, initially just a cartoon character on scorecards for New York Mets games, was fully realised in 1964 when a full-sized, costumed version began making appearances at Shea Stadium. When you explain Mr. Met in mere words – he’s a man with a giant baseball for a head – he sounds deeply weird, to say the least, but somehow still works. Although ‘retired’ for the better part of two decades, he was eventually revived after a campaign by fans in the early 1990s.

A big reason why he was quietly ushered away from the spotlight was the emergence in the 1970s of what we know today as mascots, the larger-than-life, Muppet-like creatures that you’ll see throughout this book.

The San Diego Chicken was the first, initially a promotional character for a radio station called KGB-FM (meaning he was somewhat menacingly known as the ‘KGB Chicken’ for a spell), but who became adopted by the San Diego Padres when the man who played him decided he wanted to get into games for free. The Chicken, zany antics and all, proved wildly popular, and copycats followed, the most notable being the Phillie Phanatic, broadly regarded as the model for the modern-day mascot.

These days you’ll struggle to find a major sports team, tournament or organisation that doesn’t have – or hasn’t had – a mascot, for better or worse. It’s almost a separate industry in itself; with every mascot comes merchandise, personal appearances, commercial endorsements and myriad other money-making schemes. They’ve come a long way from a dog that some students stole in the name of banter.

NAME GRITTY

TEAM PHILADELPHIA FLYERS

SPORT ICE HOCKEY

YEARS ACTIVE 2018–PRESENT

STYLE From THE WRONG SIDE OF THE TRACKS TO SESAME STREET

FAMOUS FOR THREATENING TO MURDER ANOTHER MASCOT IN ITS SLEEP

The Philadelphia Flyers had gone 42 years without a mascot, until they decided in 2018 that they could no longer be left out of the game and thus introduced a waking nightmare into the consciousness of America.

If The Muppets ever changed direction and told the story of a quiet loner who lived in a remote cabin and ate wolves while they were still alive, they would cast Gritty in the lead role. A bug-eyed orange monster with a beard, Gritty would look very at home with a rifle over his shoulder and the entrails of a rival flecked around his fur.

The thing is, though, it seems to be working. A Flyers suit once noted that Gritty would match the ‘blue-collar nature of the Philadelphia fanbase’, and after the whole of America recoiled in horror at whatever this thing was, the good people of Philly closed ranks behind their boy. He was one of theirs now. And when the Pittsburgh Penguins mascot (a penguin, as it happens) tweeted a gentle jibe in his direction, Gritty replied, ‘Sleep with one eye open, bird.’ If nothing else, the good people of Philadelphia appreciate a mascot who will murder another to defend their honour.

Len Redkoles/NHLI via Getty Images

Darmowy fragment się skończył.