Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Trickster»

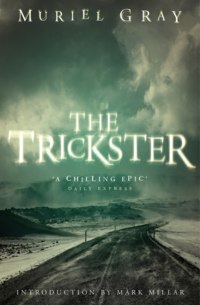

MURIEL GRAY

The Trickster

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Muriel Gray 1994, 2015

Introduction © Mark Millar 2015

Cover photograph © Sverrir Thorolfsson Iceland/Getty Images

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Muriel Gray asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008158248

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008134730

Version: 2015-10-14

For

Hamish MacVinish Barbour

and Hector Adam Barbour.

With love.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface to the 20th anniversary edition

Introduction

Chapter 1: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 54

Chapter 55: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60: Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Keep Reading

Furnace: Chapter 1

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also By the Author

About the Publisher

Preface to the 20th anniversary edition

Here’s a confession. If The Trickster had been written today instead of twenty years ago it would probably be a much lazier book. There was no internet in 1994. Well, there was a sort of internet. It was called ‘a library’.

The story grew after a two-month winter stay in the Canadian Rockies, in and around the Alberta town of Banff, named after the Aberdeenshire town by the Scots who built the great railway that opened up Western Canada to the world. That fascinating historical connection, combined with the local Native Canadian lore and backdrop of fiercely beautiful, unforgiving mountain landscape, would set any imagination alight. And it did.

The history of the Canadian Pacific Railway alone is enough to fill a whole library of books, as indeed it has, as I discovered when I set out to find more, poring over volumes in Glasgow’s grand Mitchell Library.

But as the story evolved around the native people, whose land this had been long before the Scots and their Chinese labourers arrived to lay iron rails through previously unnavigable wilderness, it was clear there was only one way to gather accurate information. Go back and talk to them.

I was warned by local non-native Canadians that trying to gain access to the Stoney Indian Tribe, whose First Nation reserve lies to the east of Banff by the small town of Cochrane, was all but impossible. Wary of outsiders, with a depressing range of serious social problems, these were not people who would be instantly eager to share tales of their ancestors with a stranger from Scotland.

But since the clan motto ‘Hold Fast Craigellachie’ was the telegram sent to the team leader nearing exhaustion during the railway construction’s most challenging section, it seemed right to follow suit.

To meet a reserve resident you make a date and a place, and then you go and wait. They don’t turn up. Well, they do. They watch you from afar. And if you keep coming back at the right time and the right place then eventually they come too.

It took nearly two weeks. Same place, same time, every single day. And then suddenly, one day I was in. My guide was a young woman, Co-Co Powderface, a champion barrel-rider and hunter. We talked and talked. We visited her home, a corrugated iron hand-built house, the tiny shack of her grandmother, a non-English speaker, and the surprise was that everything about it was resonant of lives I’d seen as a child in Scotland, when travelling in the Outer Hebrides and the far north Highlands. Strangely familiar territory.

Over the days we spent with Co-Co, her grandmother, through translation, told tales of shape shifting, of travelling hundreds of miles in minutes, of the spirits and their lives, and miserably, of darker things in their community, horribly real and human and indisputable.

So it’s to her, her family and her people I dedicate this new edition. Had I been able to travel there by clicking the internet, to browse through their myths and legends, idly gaze at photographs of First Nations reserves and forums about cultural practices and problems, I would never have had the privilege of meeting them.

Twenty years seems a long time ago. But just think. To something dark, something ancient, evil and indestructible, something that existed on earth long before the first fish crawled from the sea on its journey to evolve into mankind, it would seem no more than the sideways blink of an eye.

Muriel Gray, 2015

Introduction

I’m very suspicious of people who read introductions.

In my experience the writer’s name in big, chunky letters is all I really need to pick up a book. If it’s a writer I don’t recognize, I’ll impulse buy on a title or a blurb or, if I’m being especially reckless, a beautifully painted cover. But if you’re still unsure whether or not to immerse yourself in the story ahead and need a further thousand words to completely convince you, then let me reassure even the most cautious buyer …

This is the best decision you’ve made lately and you’re in for an absolute treat.

Let’s go back in time ten years to when I first met Muriel Gray. No, scratch that. Turn the dial a further ninety degrees, crank up the handle and send your George Pal-era time machine back a full three decades and she’s starting her career as the coolest thing on the coolest show on television. She’s a presenter on the legendary music programme, The Tube, interviewing pretty much everyone you’ve ever heard of; fast-forward and she’s a kind of a famous TV producer and Britain’s most well-known mountain-climber and a member of the board at Glasgow School of Art (where she’s DOCTOR Muriel Gray) and an award-winning newspaper columnist and former rector of Edinburgh University. Oh, she’s also the patron of several Scottish charities, a respected art historian, an architecture buff, a professional illustrator, a marathon runner, a wife, a mother and a hugely successful business-woman too, in case you didn’t get the memo.

So when I first met Muriel ten years back and discovered she had a double life as a hugely successful horror novelist with three bestselling books to her name and deified by no less than Mister Stephen Edwin King of Portland, Maine, it really didn’t come as too much of a surprise.

The British are naturally suspicious of polymaths and we’re generally right. It’s hard enough to be wonderful at one thing and close to impossible to be brilliant at everything. Yet Muriel kind of is. Oh, and lest ye worry she’s jumping on some kind of genre gravy train when everyone is keen to flash their geek credentials let me assure you she’s very much the real deal. In an era where Hollywood pours money over precisely the kind of creative types they shunned and mocked for years, to the point where the word ‘Ferd’ has been created to identify ‘fake-nerds’, Muriel’s knowledge and love of all things horror is very close to unparalleled. This is a woman who knows her HP Lovecraft from her MR James and will liberally drop names like Machen, Matheson or Algernon Blackwood into even the most casual of dinner conversations. She’s as comfortable at a horror and fantasy convention in the rainy south-east of England as in a BBC studio in Television Centre, possibly even more so. You see, this is what she REALLY wanted to do while she was winning at all the amazing things she’s perhaps better known for and, trust me, it shows.

I remember sitting down to read The Trickster with that slight trepidation when you’re friends with the author. Two pages in and I was forty pages in. A hundred pages in and I was finished. How did that happen? It was so good I genuinely started Furnace the following day and finished off the week with the third of her excellent horror trio, The Ancient. Muriel is such a natural, her writing style so easy, that I can’t believe she hasn’t dipped her toe in these murky waters for precisely 1.5 decades. The Trickster was every weather-beaten paperback, every old comic book, every cult horror movie and every videotaped Hammer House of Horror she had ever stored away in the back of her brain and it literally exploded from her head into ours. She’d trained for it her entire life and she seemed to have a ball. I did too and, trust me, so will you as you read about Sam Hunt and his mysterious heritage and the thing beneath the mountains and all these terrible blackouts he’s been having at precisely the same time all these interesting corpses are showing up. Why in the name of Great Jehovah has this woman not written a horror novel in fifteen years? Why are you reading this introduction when there’s a monster of a book on the other side of the next page?

So if you only know Muriel from TV or radio or a familiar face up a Scottish mountain or that lady with the spiky blonde hair who sits across from you at the School of Art board meetings then you haven’t really, truly met the real her. This book in your hands is the closest thing to the Muriel her friends know and love and, to be honest, I’m slightly jealous you’re only just discovering what she’s really all about in this spanking new edition you’re holding right now.

She really is brilliant at everything, but the books, I would suggest, are her finest achievement and if you’re familiar with her in any way at all you’ll know that is a pretty damn fine recommendation.

Now stop reading the introduction. Turn the page and enjoy yourself.

Mark Millar

Glasgow, 2015

1

Alberta 1907 Siding Twenty-three

When he screamed, his lips slid so far up his teeth that the rarely exposed gum looked like shiny, flayed meat. Hunting Wolf’s eyes flicked open and stared. There was a semicircle of faces above him. Silent. Watching.

For a moment he stayed perfectly still, allowing himself to regain the feeling of being inside his body, that dull ache of reality after the lightness of the spirit’s escape. Then the numbing cold of the snow beneath his naked back stabbed at his skin, and mocked him with the knowledge that he was firmly back in the realm of the flesh.

Sweat was still trickling down his breast, beads of moisture clinging to his brown nipples like decoration, and he stared up at the grey, snow-laden sky in hot despair.

The faces looked on. They would not step forward to touch him or help him in this state. The shaman’s trance was sacred and they had no way of knowing when it would be over.

But it was over, now. He had looked into the thing’s face. Oh, Great Spirit, he had. And the filthy darkness, the bottomless malice he had seen there, had been nearly impossible to bear.

The white men gathered by the mountain were insane. He had seen that, too. Their madness, their folly.

And what could he do?

The shaman got up from the ground with a swiftness that surprised his audience of watchers, and walked away. The faces regarded him for a moment, and then, one by one, followed.

2

‘The living rock.’

If Wesley Martell had caught the look his engineer threw him, he might have regretted the remark. As it was, he shifted his huge bulk in the conductor’s chair, leaned a flabby arm, its hand dimpled like a baby’s, on the sill of the cab window and said it again.

‘Yes indeed. Liiiviiing rock.’

Joshua Tennent, to whom the remark was principally addressed, returned his gaze to the track in front of them, his forefinger caressing the throttle handle as though it could make toast of his corpulent colleague. As the mouth of the first tunnel slid into view from behind a cliff crusted by aquamarine ice, Joshua felt panic mash his guts again.

How many times had he done this, for Christ’s sake? He’d pulled freight back and forwards through the Corkscrew Tunnel for nearly three years, and just because of one foolish, possibly imagined incident, he found himself nearly caking his shorts like a toddler every time that black arch yawned in front of him.

He’d guessed Martell would have a go, could tell by the way he had shifted eagerly in his seat as they’d climbed up the approach to Wolf Mountain. Joshua had hoped the lump of lard would doze illegally until they reached Silver, but he’d been alert and beady-eyed for miles. Those two serpentine tubes of blackness lay between them and town, and the conductor wasn’t in the mood for regulation-breaking sleep.

Joshua thought it best to ignore the bastard. Martell wasn’t the first to twist the knife and he wouldn’t be the last. Concentrating on smothering his fear was labour enough for now.

The conductor peeked across at his white-faced engineer, as he slapped the shoulder of the third occupant of the cab, a sullen brakeman called Henry. He gesticulated grandly towards Joshua, his two rodent-like eyes narrowing into slits of mirth.

‘Look, Henry. Hoghead’s got the jimmy-shits again ’bout goin’ through the Corkscrews.’

The brakeman disregarded both the slap and the remark, answering only with a barely perceptible upward movement of his head, the reverse of a nod. Martell was undeterred. This shift had bored the balls off him, with the brakeman sitting motionless and silent in front of him, his big ears sticking out like one of those Easter Island heads Martell had seen in a magazine once. And this damn engineer had no conversation either. Wasn’t much to ask that a man could expect a bit of parley at his work, instead of watching speechless as three hundred miles of Canadian Pacific track snaked beneath them in the snow.

There was nearly a mile of train behind them. Being in charge of a hundred cars of coal rumbling slowly across Canada meant big-time responsibility to Wesley Martell. He often pictured how his train looked from the air, a giant metal caterpillar picking its way through the mountains, the engine like the insect’s head, and himself, CP conductor, Martell, the brains in that head. This mile of hardware stopped, started or stayed at his say-so, and that made him feel good; made him more of a man than those jockeys braying into portable phones you saw on the sidewalks in Vancouver. No kid was ever going to look at those guys with big, wide, jealous eyes when they went about their business, least not the way they looked up at him in his cab, when he hi-balled his monster load through a station waving down at them like an oily Father Christmas.

But Martell didn’t get to be conductor, the big cheese on this buggy, without expecting a crumb of respect from his crew. Part of that respect was the civility to pass the time, jaw a little.

Seemed like this crew didn’t know the meaning of the word respect, sitting there like two dumb fucks, lost in their own dumb thoughts.

Wesley Martell didn’t much like to be left alone with his thoughts: too much track gazing and those thoughts had the habit of chucking up things he’d rather not meet again, thanks. Especially on a night haul, when the lights of the train illuminated a few yards of the track ahead, making it dance and gyrate on the edge of darkness like something alive. No, he’d rather talk. Talk was life. Silence was a kind of death, and he’d had enough silence on this journey.

Ten miles back Henry had said something to Joshua that Martell didn’t catch, and apart from that, nothing. Not a sound except the clacking of the wheels on the track and the throaty roar of the engine. So when the Corkscrew Tunnel rolled round, Martell took his shot.

Back at the depot, Joshua and his tunnels were the butt of an endless running joke amongst the local crews, and Martell was damned if he wasn’t going to use anything he could to get a little spark into this seven-hour bitch of a shift.

Joshua was still, quiet, and white. He had it coming.

‘Best keep a hand on that throttle, engineer. Think I saw something movin’ in there.’ He threw his head back and wheezed out a guffaw.

He laughed alone, but Henry turned his head slightly towards Martell before returning to gaze vacantly out of the window.

Joshua could feel his hands turning clammy. It wasn’t hard to ignore the fat guy. Ever since he’d confided in some brakemen from Toronto what had happened to him that day in the tunnel, he’d taken a ribbing that was now so obligatory it had practically entered the Canadian Railway Operating Rules Book.

What was hard, and getting harder every time they came through, was trying to resist jamming the dynamic brake handle on and jumping out of the train cab into the snow, before the three men and those hundred cars of grade one coal were launched into the gaping black mouth.

Funny to think that right now, on the wooden viewing platform up on the highway, tourists would be yelping to each other like excited coyotes, at spotting a freight train about to go through the famous tunnels. It was a Kodak-moment, all right: with a train as long as this one, the onlookers would see the engine disappear into the first tunnel, then double back on itself, only to appear to be travelling in the opposite direction to its freight before entering the second tunnel. There was a big painted illustration up on that platform for the real dumb tourists, the ones who stumbled out of a Winnebago and couldn’t figure out where they were, never mind what they were seeing.

Joshua had stopped on the highway once to look at the sign. It told him in kiddie-speak letters that they had blasted into the mountain ninety years ago, using the spiral design to avoid a wicked gradient through Wolf Pass. There were shitty pencil drawings of pioneers with big hats and moustaches, and a lot of bull about the early days of railway, but at least there was a diagram of how the tunnels worked inside the mountain. That was neat. You could see exactly how the Corkscrew worked, how it quartered the gradient with those two curly holes in the hill. Joshua had never thought about it much before then, and he didn’t think about it much after either. That is, until he had his fright.

It didn’t matter how many times he went over it in his head. He’d lain awake at nights in the CP bunkhouses and at home in Stoke, trying to figure out why he’d gotten scared. Worst thing was, it was a whole year ago, almost exactly this time last winter, and the scare hadn’t worn off.

Martell could go shaft himself. Joshua would tolerate all the fat fingers in the world poking him in the ribs, if he could just shake free of this paralysing, childish fear. He began to run through it again, the way he did every time they passed this way, trying to flush the memory away, make it safe.

The way he remembered it, they’d come through the lower tunnel, the engine just entering the second, when the End-to-Train unit had gone apeshit. There was a hot box back there and nothing for it but to stop. With the gradient they had to negotiate coming up before the higher tunnel, the last thing they needed was a car with screaming white-hot axles dragging behind them. Joshua recalled whistling through his teeth with exasperation as the whole damn hulk screeched to a halt and conductor and brakeman got up from their chairs and stretched their legs.

The boxes had stopped out there in the gorge, sitting in the thin wintry sunlight, leaving the cab of the engine about fifty yards into the tunnel, and Joshua knew he had to get back there and investigate. Barney the brakeman handed Joshua a thick black rubber torch with one hand and put the kettle on the hot plate with the other, saying clearly without words that the engineer would have their assistance when they were good and ready.

It was the delay that had pissed off Joshua. Just the time it was going to take to check it all out and put it right. It had been his homeward shift, taking him back to Beat River and Mary’s bed, a heavenly prospect after five nights in the bunkhouses, lying beside guys in their pits, snoring like they were sawing logs. He remembered thinking two things. The first was that at least it was lucky the cars had stopped outside the tunnel, and the second thought, like it had come from nowhere, was ‘the living rock’. Three innocent words, just sitting there doing nothing, going nowhere, meaning little. But there.

He took the torch and saluted sarcastically to Barney as he opened the cab door and left.

As he climbed down out of the huge red DRF30, Joshua touched the hand rail with an ungloved hand. Cold metal that has just rolled through the passes between the Alberta Rockies in minus twenty is not welcoming to naked flesh, and Joshua’s fingers stuck fast, forcing him to breathe on them to release his hand. It stung like crazy as it relinquished his grip and with a curse he sheathed it in a leather work gauntlet.

It was the only time he’d ever stopped in the tunnels, and yes, compared to the cement-lined tunnels that ran under the highways on the east coast, the rock was alive all right. So much for ‘a feat of grand engineering’. Seemed like the guys had just blasted the sucker and left. The walls and ceiling surprised him with their unhewn crudity, something he had never perceived by the weak light of the cab as they’d passed through here a hundred times. Ice hung from every crack in thin savage spikes and sporadically coated the rock-face with vast, glistening bulbous sheets.

And everything was dark ahead of the engine. Really dark. The curve of the tunnel meant that you could only ever see one entrance at a time. In fact, there was a point, right in the middle of the tunnel’s arc, where you couldn’t see any light at all; but he didn’t care to think of that right now. His breath billowed up in front of his face like steam, partially obscuring his view of the sunlit opening ahead each time he exhaled.

He should have been thinking about how they were going to get to the maintenance yard forty kilometres away without too much damage or time loss: he should have been thinking like an engineer. But he wasn’t. All he could hear, echoing in his head as though his skull were a tunnel, were the words, the living rock, the living rock.

He hadn’t needed the torch for the first few yards, the walls being lit by the cab interior, but by the time he drew level with the first car, Joshua had to use it, picking his way along the track trying not to pratfall over the sleepers half-buried in gravel. The arch of sunlight was clear ahead, its illumination extending barely a few feet into the dark, and already he was starting to regret he hadn’t insisted that Barney come with him. He touched the walkie-talkie hanging on his hip, annoyed that it hadn’t crackled into life. Clearly his two crew companions were treating this like a break instead of a breakdown. He was tempted to press ‘talk’ and shout horse’s ass at them as he passed the second car just to remind them he was there, but realized grimly that it wasn’t irritation making him keen to summon them, but apprehension. His hand left the radio, unclipped the ear flaps on his cap and let them fall. Joshua Tennent was suddenly very cold.

It wasn’t so much a noise he heard, more the feeling of a noise. That is, he sensed there was something scraping in the rock above him. Not scraping on the surface, like a bat or a chipmunk, but scraping inside the rock as if the stone itself was shifting, turning in its sleep.

But he didn’t hear it. He felt it. The tunnel was not silent: the idling engine hissed and clanked, dripped and cracked at random as he progressed along its metal flanks. Any rustling in the tunnel would have to work hard to make itself heard above the cacophony.

Even now, he still couldn’t say which sense was being alerted, but the memory of the feeling was pungent.

At first he ignored it. How could you feel a noise? Walking on, he realized that he hadn’t breathed for about six or seven seconds and corrected the oversight with a cloud of vapour. He struggled to free his body from that atavistic state of standby every child adopts in the darkened bedroom when they hear a creak from a floorboard; breath held, eyes wide open, body still and ready to flee. But why was he on red alert? There was nothing to fear in this situation, except the diminishing drinking time in Stoke, and the wrath of Mary, who even now would be soaking in a bath reeking of something made from coconut or peach.

He felt it again. It was above him, he was sure of that. Something stirring in the rock above the ceiling. But no, that wasn’t right. It was the rock in the ceiling itself that was stirring, moving above him like iron filings attracted to his magnet.

Joshua wanted to run then. He wanted to run very badly indeed. But from what? There was no sound, for God’s sake, nothing to hear but the train. If he gave in to his instincts, how would he explain to Barney or the conductor why he ran flailing along the track, stumbling into the sunlight like a fool? He kept that picture close as he walked more quickly towards the tunnel mouth, making himself visualize Barney’s face as he described how a sound ‘felt’.

‘You bin drinkin’ meths?’ he would say for sure. Barney’s favourite joke. A joke he used on anything he didn’t agree with, understand or like.

(Union official tells him there’s an overtime ban.

‘You bin’ drinkin’ meths?’

Wife tells him it’s time he got up off his fat fanny and put the trash out …

‘You bin drinkin’ meths?’)

You see Barney, you couldn’t hear it exactly, you could only feel it …