Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «In the Mouth of the Wolf»

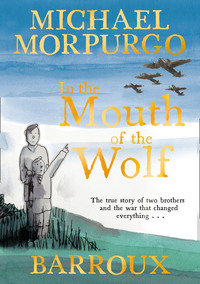

First published in Great Britain 2018

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2018 Michael Morpurgo

Illustrations copyright © 2018 Barroux

The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material

reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will

be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

All images used with thanks.

Two images of Christine Granville here © The Estate of William Stanley Moss

ISBN 978 1 4052 8526 1

eISBN 978 1 4052 9274 0

65511/1

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the CPI Group

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the

publisher and the copyright owner.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at

the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content

hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and

websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are

supervised when using the internet.

Egmont takes its responsibility to the planet and its inhabitants very seriously.

All the papers we use are from well-managed forests run by responsible suppliers.

For Nan and Francis,

Niki, Jay, Christine and Paul.

And Kia.

In memory of Yves Barroux.

For Marie-Thérèse and Sophie-Laure.

T

hey gave me such a jolly party today. Everyone

from the village came.

Ninety years old, I am. I’m walking a bit stooped

these days, and my knees and hips are more rickety than they should be, but I can walk up into the village, and I still like a good meal, and a glass of good red wine –

I had plenty of that this

evening. Sleep does not

come so easily as it did,

but I mustn’t grumble. I

have my memories, and

friends all around me,

and family too, those who

are still alive. What more

could an old man want?

1

A better memory would be good. I’m fine with faces and places. It’s the years that get muddled, jumbled up. I spend my time trying to unjumble them.

The village mayor made a generous speech, and said how honoured they were to have Monsieur le Colonel Francis Cammaerts – such a great man, and such a great friend to the people of Le Pouget,

and of France – living here in their little French village, and his family too. The school children stood in the courtyard, with their Union Jack and Tricolour flags, and sang ‘Sur le Pont d’Avignon’ and ‘London Bridge is Falling Down’ as well, and everyone clapped and sang ‘Happy Birthday to You’, in English and in French.

3

A little girl stepped forward to present me with some flowers. Red, white and almost-blue irises. Lovely. The mayor said she was the newest girl in the school, that she had recently come from Punjab to live in the village. She spoke with quiet dignity, and in good French. ‘I am Jupjaapun Kaur. From all the children in Le Pouget I wish you a most happy birthday.’ I repeated her name again and again to be sure I was pronouncing it right.

She smiled at me, and told me that Kaur means princess. The flowers, she said, came from her garden.

I was so glad at that moment that we’d come back to live in France, but sad that not all of us were here, that Nan and our Christine were not with us. Several others too. I miss them more today than ever. But I have Paul, and I have Niki. And Jay.

A wonderful son and two dear daughters, and little Kia, who is no longer little at all – grandchildren grow up even faster than your own children. I should be thankful.

4

And I am, I am. But I am in the dusk of my life, a dusk that is streaked with joys, and sadnesses.

I was suddenly tired and longing for the solitude and quiet of my little room, and bed. I waved them all goodbye. Jay helped me into the house, and into bed, hugged me and left. What children I have, what friends they are to me!

So here I am now, in my bed. Night has fallen. The bright moon shining in through the window, and the church bell striking midnight. My scops owl hoots his birthday greeting to me. I smile in the moonlight and settle back on my pillows. I know I won’t sleep.

This is a night for remembering. I want to remember everyone who wasn’t here at my party, all my good companions in life who held my hand, stroked my brow, helped me through. I want to see them again, be with them again, live all my life with them again, from my sandpit days to now. Ninety years.

P

apa, are you there, Papa? You missed a good party. I think of you, and you are sitting there in your

tweed suit, with your bird’s nest of a beard, wreathed in pipe smoke. I always wanted to be like you, Papa, smoke a pipe, write fine poetry, stories and plays, be wise. You were so wise about most things – but not

everything. For a start, you had far

too many children. Four

daughters, all of them

loud with laughter

and full of opinions

– Marie, Elizabeth,

Catherine, Jeanne

– and then there

was Pieter and me;

9

‘the boys’, you called us. There were children tumbling

everywhere, crowding me out of the sandpit, and forever

making plays where I always had to be a tree, because I

was tall.

The sisters chose the plays, took the main parts too.

Pieter was the best actor, but they made him play the

log that Bottom sat on in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

10

Do you remember that, Papa? And I was a tree again of

course. You said Pieter made a very fine log, but you said nothing about me being a very fine tree.

I always liked to have you

to myself, but hardly ever

could. You never read the poems and

stories just to me, always to all of us. I loved the stories,

loved the poems, but I loved you more.

You remember those summer holidays in Belgium, Papa, the country walks in the Ardennes forest where you had grown up as a child? Those were the best times, Papa, just you and me, and Pieter trailing along behind, waving a stick. He always had a stick. I asked him once why he was fencing with it, and he said he was fighting off the wolves. And I said there was no need to fight them, that he could turn and face them, and clap his

11

hands and look brave. And Pieter said no, that if they came close and bared their teeth, if they wanted to eat him up, if they wanted to tear our family to pieces, he had to fight them.

You said, Papa, in your wisdom, in your desire always to be fair, that we were both right. But you had told me all my life that it was ignorance and ancient hatreds and power politics that had dragged Europe into the horrors of the Great War, and that in that war, as in all wars, there were never winners, only sufferers. You set me on my pacifist course early, Papa. It is a philosophy that has guided me and troubled me all my life.

Who knows why you sent me off to that boarding school, banishing me from the family home, from all that was familiar – from you? I was never so miserable, before or since. I lay in my bed each night and raged against you and Mama. I grew away from you, from home and family, more and more each night. In time, Pieter came to join me, and we should have been allies then. But I

14

was older, taller, domineering, and I am ashamed to say, Papa, that I neglected him dreadfully. Worse, I turned my back on him as a brother. He was a new boy, a squirt. I treated him with disdain, disowned him sometimes. I have never forgiven myself.

If I am honest, I think there was jealousy there. I might have been a big cheese, was taller than any other boy in the school, a giant on the rugby field, always surrounded by friends, but Pieter was beautiful, with

15

the face of a young god, kind-hearted always, Mama’s favourite, and at home so full of fun and laughter. But not at school. This was not a place for sensitive souls. He hated it as much as I did.

You didn’t know any of this, did you, Papa? We kept our school life separate, Pieter and I. At home I could be more like a proper brother to him again. Free from the tyranny of that school, we could be ourselves, be brothers, be the best of friends. But, away from you, Papa, I stopped

knowing you. I stopped knowing you, even stopped

loving you for a while. Home was a foreign land to me.

You were busy becoming Emile Cammaerts, travelling up

to London every day, the great professor and poet.

There were no more family holidays in the Ardennes,

no more walks and talks in the forest, just you and me.

There was civil war raging in Spain, Hitler’s bombs

were falling on Guernica, on families, on old and young

alike. And in Germany and in Italy, fascists were on

the move. The world was resounding to the march of

jackboots, the drums of war were beating.

I did my university degree in Cambridge, living the last of the good life, turning a blind eye, hoping for the best, but fearful already that the Great War into which I had been born was not going to be the war to end all wars. I turned to teaching, not out of conviction, not yet, but for lack of anything else to do. You approved, and told me I would make a great teacher. I wanted so much to believe that.

I hardly saw Pieter those days. He was going his own way, as a proper actor – not just a log any more – travelling

the country. If I ever came home, you would show me his reviews proudly. You forgave me for drifting away, let me become whoever I was going to become. You trusted me, and that takes love, I know that now. You made me who I am, Papa. And Pieter? Well, Pieter changed the whole course of my life.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.