Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

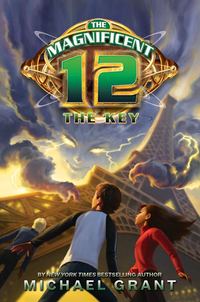

Czytaj książkę: «The Key»

For Katherine, Jake, and Julia

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Last Chapter Before the Next Book

Notes

Other Magnificent 12 books by Michael Grant

Copyright

About the Publisher

Let me out of here, you crazy old man!” Mack cried.

“Ye’ll ne’er lea’ ’ere alive. Or at least ye wilnae be alive fur lang. Ha-ha-ha!” Which was Scottish, more or less, for, “You’ll never leave here alive. Or at least you won’t be alive for long. Ha-ha-ha!”

The Scots are known for butchering the English language and for their ingenuity with building things. The first steam engine? Scottish guy invented it. The first raincoat? A Scot invented that, too. The first television, telephone, bicycle—all invented by Scots.

They’re a very handy race.

And the first catapult designed to hurl a twelve-year-old boy from the top of the tallest tower in a castle notable for its tall towers? It turns out that, too, was invented by a Scot, and his name was William Blisterthöng MacGuffin.

The twelve-year-old boy in question was David MacAvoy. All his friends called him Mack, and so did William Blisterthöng MacGuffin, although they were definitely not friends.

“Ye see, Mack, mah wee jimmy, whin ah cut th’ rope, they stones thare, whit we ca’ th’ counterweight, drop ’n’ yank this end doon while at th’ same time ye gang flying thro’ th’ air.”

Mack did see this.

Actually the catapult was surprisingly easy to understand, although Mack had never been good at science. The catapult was shaped a little like a long-handled spoon that balanced on a backyard swing set. A rough-timbered basket full of massive granite rocks was attached to the short handle end of the spoon. The business end of the spoon, where it might have contained chicken noodle soup or minestrone, was filled with Mack.

Mack was tied up. He was a hog-tied little bundle of fear.

The spoon, er, catapult, had been cranked so that the rock end was in the air and the Mack end was down low. A rope held the Mack end down—a rope that twanged with the effort of holding all that weight in check. A rope whose short fibers were already popping out. A rope that looked rather old and frayed to begin with.

William Blisterthöng MacGuffin, a huge, burly, red-haired, red-bearded, red-eyebrowed, red-chest-haired, red-wrist-haired man in a plaid skirt1 held a broadsword that could, with a single sweeping motion, cut the rope. Which would allow the rocks to swiftly drag down the short end of the spoon while hurling Mack through the air.

“Ye invaded mah privacy uninvited, ye annoying besom. And now ye’ve drawn the yak o’ th’ Pale Queen, ye gowk!”

Or in decent, proper English, “You invaded my privacy uninvited, you annoying brat. And now you’ve drawn the eye of the Pale Queen, you ninny.”

How far could the catapult throw Mack? Well, a well-made catapult . . . actually, you know what? This particular kind of catapult is called a trebuchet. Treh-boo-shay. Let’s use the proper vocabulary out of respect for Mack’s imminent death.

A well-made trebuchet (this one looked pretty well made) can easily hurl 100 kilos (or approximately two Macks) a distance of 1,000 feet.

Let’s picture 1,000 feet, shall we? It’s three football fields. It’s just a little less than if you laid the Empire State Building down flat. It’s long enough that if you started screaming at the moment of launch, you’d have time to scream yourself out, take a deep breath, check your messages, and scream yourself out again.

That would be pretty bad.

Unfortunately it got worse. The castle tower was about 300 feet tall. The castle itself sat perched precariously atop a spur of lichen-crusted rock that shot 400 feet above the surrounding land.

So let’s do the math. Three hundred feet plus 400 feet makes a 700-foot vertical drop. And the horizontal distance was about 1,000 feet.

At the end of all that math was a second ruined castle, which sat beside Loch Ness.

In Loch Ness was the Loch Ness monster. But Mack wouldn’t be hitting the lake; he’d be hitting the stone walls of that second castle, Urquhart Castle. He would hit it so hard, his body would become part of the mortar between the stones of that castle.

“Dae ye huv ony lest words tae say afore ah murdurr ye?”

“Yes! I have last words to say before you murder me! Yes! My last words are: don’t murder me!”

Mack could have used some magical words of Vargran. He was totally capable of speaking it. Totally.

If.

If Mack had taken some time to study what words of Vargran had been given to him and his friends. Sadly, when Mack might have been studying he rode the London Eye Ferris wheel instead. And the next time he could have been studying he downloaded a game on his phone instead and played Mage Gauntlet for six hours. And the next time . . . Well, you get the idea.2

So instead of whipping out some well-chosen magical words, Mack could only say, “Seriously: please don’t murder me.”

Which is just pathetic.

Look, we all know Mack is the hero of the story. And we all know the hero can’t be killed. So there’s no way he’s just going to be slammed into a ruined castle and—

“Cheerio the nou, ye scunner,” MacGuffin said, and he swung the sword.

The blade parted the frayed rope.

But wait, seriously? Mack’s going to die?

Gravity worked the way it usually does, and the big basket of rocks dropped like a big basket of rocks.

Hey! If Mack dies, the world is doomed and the Pale Queen wins!

“Aaaahhh!” Mack screamed.

He flew like a cannonball toward certain death.

Let’s avert our gazes from the place and moment of impact.

No one wants to see what happens to a kid when he hits a stone wall—it’s just too gruesome and disturbing. So let’s back the story up a little and see how Mack got himself into this mess to begin with.

In fact, let’s do some ellipses to signal that we are going back in time . . . to the day before . . .

Before . . .

“Ahhhhh!” Mack cried, gripping the dashboard. He was seated next to Stefan, who was driving.

“Aieeee!” Xiao cried, gripping the back of Mack’s seat.

“Acchhh!” Dietmar cried, hugging himself and rocking back and forth.

“Yeee hah!” Jarrah shouted, flashing a huge grin as she pumped her fist in the seat behind Stefan.

A car—it happened to be yellow—roared straight for them, horn blaring, headlights flashing, driver forming his mouth into a terrified O shape.

Stefan jerked the wheel left and stomped on the gas. This was accidental. He had meant to stomp on the brakes but he was confused. He didn’t really know how to drive.

“Other way, other way, otherwayotherwayother-way—aaaaaaaahhhh!” Mack yelled as Stefan drove the rented car into a traffic circle.

Now, in most of the world the cars in a traffic circle go counterclockwise. The exceptions are England, Wales, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, a few other countries, and Scotland.

This happened to be a Scottish traffic circle.

Those of you who’ve read the first two books about the Magnificent Twelve may recall that our hero, Mack MacAvoy, was twelve years old. In fact, being twelve was an important part of being a member of the Magnificent Twelve. Because it wasn’t just any random twelve people. It was twelve twelve-year-olds, each of whom possessed the enlightened puissance.

And remembering that, you might also be thinking, Who rents a car to a twelve-year-old?

Well, perhaps you’re forgetting that Stefan was fifteen—although he was in the same grade as Mack. Stefan, not being one of the Magnificent Twelve, but more of a bodyguard, could have been any age. He happened to be fifteen, and he looked eighteen. Which is still not old enough to be renting a car. Especially when you don’t have a driver’s license.

But you may also remember the part about Mack being given a million-dollar credit card.

Cost of car rental: 229.64 GBP.3

Cost of the gift certificate to Jenners department store in Edinburgh in the name of the car-rental clerk: 3,000.00 GBP.

Yeah: it’s amazing what you can do with a million dollars. Renting a car is the least of it.

“There’s a truck!” Mack shouted.

“It’s called a lorry here!” Dietmar yelled in his know-it-all way.

“I don’t care if it’s called a—”

“Jog a little to the right there,” Jarrah suggested quite calmly, and put her hand on Stefan’s powerful shoulder. Stefan did as he was told.

The truck or lorry or whatever it was called let go a horn blast that could have shattered a plate glass window and went shooting past so close that, bang, it knocked the left side mirror off the little red car.

“The mirror!” Xiao cried.

“Enh,” Stefan said, and shrugged. “I wasn’t using it anyway.”

He wasn’t. As far as Mack could tell, Stefan wasn’t even using the windows, let alone the mirrors, and was more or less driving according to some suicidal instinct.

The car had seemed like a bad idea from the start, but Mack didn’t like to come across all bossy, or like he was a wimp or something. One of the problems with having twenty-one identified phobias—irrational fears—is that people tend to think you’re a coward. Mack was not a coward: he just had phobias. Which meant there were twenty-one things he was cowardly about—tight spaces, sharks, needles, oceans, beards, and a few others—but he was brave enough about most things.

So when it had been pointed out to him that having made it by train from London to Edinburgh, Scotland, the best way to get from there to Loch Ness was by car, he’d gone along. To demonstrate that he was not a huge wimp.

How was that going? Like this:

“Gaaa-aah-ahh!” Dietmar commented.

BAM!

Rattle rattle rattle rattle.

Thump!

The car hit the low curb guarding the center of the circle, bounced over the lumpy grass, swerved around some sort of monument, narrowly missed a pair of Mini Coopers—one red, one tan—and bounced out of the other side of the circle and onto the main road.

Mack, Xiao, and Dietmar all took the first breath they’d inhaled in several minutes.

Stefan said, “Is there a drive-through in this country? I’m starving.”

And Jarrah said, “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse and chase the jockey.”

Jarrah and Stefan: obviously they were not quite normal.

Having survived the traffic circle, the gang found a gas station that also had food. They bought prepackaged sandwiches and sodas. They topped the car off with gas. And that’s when Mack noticed a van he had noticed earlier. There was nothing remarkable about the van—it was beige, which is the world’s least noticeable color. But Mack was a kid who noticed things and he noticed that this van had a dent on one side. A small thing. But what were the odds that there were two tan vans with the same dent?

He had first noticed this van way back just outside Edinburgh, and now that Mack looked closer, it seemed the windshield was tinted. Which would be a perfectly normal thing where Mack was from—the Arizona desert, where the sun shone 360 out of 365 days—but was pretty strange here in Scotland, where the sun shone 5 days out of 365.

“That van has been following us,” Mack said as the five of them leaned against their car eating.

No one questioned him. They’d all learned that when Mack noticed something, he noticed it right.

So they leaned there and watched the van. Which maybe was watching them back.

“I’ll go ask them what’s up,” Stefan said.

“No,” Mack said, shaking his head. “Maybe it’s a coincidence. Maybe they’re just going to the same place we are.”

“That is perhaps likely,” Dietmar said. “Loch Ness is very famous, and people will be coming from all over to see it.”

Dietmar spoke flawless English but his accent was strange at times, and Mack had to struggle to resist mocking him. As leader of the group, Mack had to behave in a very mature way. Mostly he did. But in his mind he was saying, “Zat iss peerheps likely,” in a snooty voice.

He didn’t dislike Dietmar; Dietmar was fine. But it wasn’t possible to like everyone equally. Dietmar was very smart and made sure everyone knew it. And he was better-looking than Mack—at least Mack thought so, since Dietmar had perfectly straight blond hair while Mack had boring curly brown hair. As a result of that, Mack was pretty sure Xiao thought Dietmar was fascinating.

Mack, however, found Xiao fascinating. So he didn’t really want her to find Dietmar more fascinating than him. Mack wasn’t exactly sure why he found Xiao so interesting. A year ago he would have barely noticed her if he’d met her. But lately he had looked with slightly more interest at girls. It wasn’t a really focused attention just yet. But it was attention.

Possibly it was because he had seen Xiao in her true form. She was, after all, a dragon. Not a fire-breathing, leathery-winged type, but the less terrifying and more spiritual Chinese dragon, with a father and mother who didn’t need to breathe fire to scare the pee out of Mack.

Xiao could turn effortlessly into her current form: a pretty girl. But she insisted the other shape, the somewhat large, turquoise, snakelike form was her true self.

“Dietmar,” Xiao said, “what do you think we should do?”

“Me?” Dietmar squeaked. Because he did that sometimes when Xiao talked to him. Squeak.

It was really annoying.

“Yes, Dietmar, I am asking your opinion,” Xiao said patiently.

“I think we should not confront them. We should merely watch and be prepared.”

“I agree,” Xiao said.

“I think Stefan should go knock on their window and ask them what’s up,” Mack said. That was not what he had thought or said, oh, sixty seconds earlier, but it was what he thought now.

Stefan hesitated. He looked at Mack. Then he looked at Jarrah, who gave a brief nod.

The Aussie girl and Stefan had a special bond. It was the mystical bond that joined the kind of people who think it would be fun to strap rockets to bikes and fly over the Grand Canyon.

That’s not some made-up example. That’s from an actual conversation between Stefan and Jarrah.

Stefan swaggered over to the van and tapped on the window with his knuckles. Mack tensed. The van window rolled down.

Stefan talked to someone, leaned in to listen, then stepped away as the window rolled back up. He came back to report to Mack.

“It’s a bunch of fairies.”

“Fairies?”

“Like with wings?”

“I think so,” Stefan said. “They say they have a proposition.”

“A proposition?” said Mack.

“That’s what they said,” said Stefan.

“A van full of fairies,” Mack repeated.

Stefan nodded. “They want to talk to you in a safe place. Someplace neutral. That’s what they said. They said there’s a magical woods down the road.”

That left them all staring blankly at Stefan.

“What do they want?” Jarrah asked.

Stefan shrugged. “They want Magnum bars. Five white chocolate and one Mayan Mystica. They said they’re for sale in the mini-mart here. They can’t go in themselves. Because, you know, they’re fairies.”

“We should buy them these ice-cream bars,” Dietmar said. “Then we should talk to them and see what they want.”

This was a problem for Mack because he agreed with Dietmar. But he didn’t want to look like he was following Dietmar’s lead. But there was no way around it: if a vanload of fairies wants to talk to you, you can’t exactly blow them off.

So the Magnifica plus Stefan went in and bought the Magnum bars. Except for the Mayan Mystica because the store was out of that flavor. Stefan had to be sent back to the van to learn whether a dark chocolate would do. (Yes.)

Stefan delivered the ice cream to the fairies.

Spent at Shell station: 11.15 GBP.4

They waited for several minutes while, Mack assumed, the fairies ate. Then the van pulled out smoothly, and with a lurching of grinding gears, a crushed trash can, and a scream of terror from a mother pushing a stroller, Mack and his crew followed.

They drove for about a mile before pulling up in sight of Urquhart Castle, an ancient ruin that perched picturesquely beside Loch Ness. The van slowed to a stop in a place where there quite clearly were no woods.

The van waited and Mack and the Magnifica waited until several cars passed by. Then, when the coast was clear, the van drove straight into a stand of trees that had absolutely not been there ten seconds earlier.

Mack didn’t know much about trees. Unfortunately, Dietmar did.

“These are holly and rowan. Superstitious folk believe they have magical properties.”

“Well, since this forest wasn’t here until, like, just now, I guess maybe they’re right,” Mack said.

Even though the day was weakly sunny, it was dark in the woods. The van rolled to a smooth stop on a bed of fallen leaves. The car rolled into a bush, sending birds squawking away in terror. The car jerked hard a few times. Then it emitted a disgruntled farting sound and finally stopped.

The window of the van rolled down again, and out flew things sparkly and golden: the ice-cream bar wrappers.

The door opened. The fairies did not step out; they flew, six of them in all.

Having by this time been in close contact with insectoid Skirrit, treasonous Tong Elves, and disgusting Lepercons, not to mention several horrifying monsters that Risky had morphed into, Mack was ready for just about anything. So it surprised him that the fairies looked almost exactly the way he expected fairies to look.

Three were male, three were female, and all had toned little bodies clad in earthy colors. They had double wings, like dragonflies, that made a buzzing sound (again, like dragonflies) as they flew. They were all roughly the same size, each maybe half a kid in height. Or at least half a Mack. Maybe a third of a Stefan.

The surprise was not in their look: these were definitely garden-variety, standard-issue fairies. The surprise came when they opened their mouths.

“I’m Frank. This is my crew: Joey, Connie, Pete, Ellen, and Julia.”

“These are not proper fairy names,” Dietmar observed.

Frank squinted. “What are you, the fairy police? Our names are whatever we say they are.”

But Dietmar wasn’t having it. “A fairy should be named after a flower or a tree, or something in the natural world.”

“And a kid should learn to keep his mouth shut,” Frank snapped. And with that, he drew what had at first looked like a small sword hanging at his side. It turned out to be a droopy sort of wand.

“You like flowers? Be one,” Frank said. He waved his wand and said, “E-ma exel strel (click)haka!”

“That’s Vargran!” Jarrah said.

And Dietmar probably would have agreed except for the fact that his body had turned green and very thin. Tubular, one might even say. His arms flattened into graceful leaves. And his head formed first a tight, green bulb and then exploded outward as the petals of a magnificent-looking sunflower.

From the seedpod at the center, Dietmar’s two eyes stared in shock. Frank did not seem to have bothered to give him a mouth.

Mack was torn between terror—understandable—and a feeling of glee—also understandable but not really admirable.

Xiao’s eyes narrowed, and already blue scales were covering her body as she—

“Uh-uh-uh!” Frank warned, shaking his finger. “That would be a bad move, dragon girl. Your kind signed a treaty a long time ago. This is western dragon territory.”

Reluctantly Xiao melted back to purely human form.

“Now, can we talk business?” Frank asked.

“You have to change Dietmar back to normal,” Mack demanded, somewhat forcefully, almost as though he meant it.

“When we’re done talking business.”

“Okay, what business?”

Frank shot a coy look at his crew, who fluttered slightly, then settled toward the ground. The instant their bare toes touched the lush grass, their wings rolled up. Like rolling up a window shade. Just rolled up. Whap.

“We hear you’re looking for someone,” Frank said.

They were, in fact, looking for the Key. The Key to Vargran spells and curses. So far they’d found bits and pieces of Vargran, but now, as they neared the fateful confrontation to save the world from the Pale Queen, they needed more. A lot more. And the Key was . . . um . . . the key.

That’s right: the Key was the key.

The Key had two parts. The first had been given to them by Nott, Norse goddess of night. And if you believed Nott (and seriously, how could you not believe a mythical Norse goddess?), the second and final part of the Key had been buried with one William Blisterthöng MacGuffin.

“Maybe,” Mack said cautiously.

“No maybe about it, kid. You’ve been asking around about someone no one has seen in a long time. We have good sources.”

Mack glanced at his companions. Jarrah shrugged.

And Mack’s iPhone chimed with the tone it used to signal a message.

Mack ignored it, but it was an edgy sort of ignoring, like he was forcing himself to ignore it, which just made everyone uncomfortable, and finally Frank said, “Oh, just go ahead and get it.”

With an abashed smile, Mack pulled out his phone.

“Well? What is it?” Xiao asked impatiently.

Mack sighed. “It’s my golem. He’s refusing to shower in the boys’ locker room.”

“Lotta dudes are bashful about that,” Stefan said, and no one thought he was talking about himself because Stefan was incapable of bashfulness.

“It’s not about being shy,” Mack said with a sigh. “He’s made out of mud. That much water . . .”

“Kind of busy here,” Frank interrupted impatiently. “Anyway, it’s best not to coddle golems. They just get needy.”

“I’ll just take a minute to . . .” His words faded out as he thumbed in a response:

You have got to handle these things yourself. You have got to be a big boy now.

“Sorry,” Mack said of the interruption. “You were saying?”

“We were saying you’re looking for someone who’s been gone a long time.”

“Let’s say we are,” Mack conceded. In the back of his mind he was wondering whether he’d been too harsh with the golem.

“Well, the someone you’re looking for is hidden by fairy enchantment. Been hidden for more than a thousand years.”

“Are we talking about the same man?” Jarrah asked.

“If it’s William Blisterthöng MacGuffin, then we are talking about the same man,” Frank confirmed. His eyes narrowed and his sharp little fairy teeth showed behind tightened lips. “And you’ll never find him. Never! Never . . . without our help.”

“Why would you help us?” Mack asked.

Frank shrugged. “A friend of ours wants something in return. Something you might be able to get for her. One hand washes the other. I scratch your back, you scratch mine. Tit for tat.”

“Can we stop being cryptic, please, and get to the point?” Xiao asked politely. “My friend is not happy as a flower.”

Dietmar was unhappy with good reason—a pair of crows came swooping down and lit on Dietmar’s huge petals and began to pick at the seeds.

“Hey, hey, get out of here!” Jarrah waved them off, but they retreated only as far as a low tree branch and from there kept a close eye on Dietmar’s sunflower seeds.

“You tell the tale, Connie—you tell it best.” Frank indicated one of the female fairies, a dark-haired, dark-eyed, tiny little beauty in a deep-green formfitting outfit.

“How do you suppose MacGuffin came to be called Blisterthöng?” Connie asked rhetorically in an enchanting fairy voice. She kind of writhed or danced as she spoke. It was a sort of dramatic interpretation: she used sweeping hand gestures, and sometimes lowered her head in sadness, or threw open her arms to show joy. “For many long years after the Romans left, and after the druids faded, and as the new faith was coming to Scotland, the fairies lived in peace. We are a peaceable folk. No fairy has ever raised a hand in violence against another!” She made a very dramatic upraised-fist move on that last line.

Mack nodded thoughtfully because that seemed like the thing to do.

“Except for the Seventeen Year War,” Pete the fairy interjected.

“And the War of the Sweltering Cave,” Julia added helpfully. “And the Rabid Peace of Kilcannon’s Bluff.”

“With those few exceptions, no fairy had ever raised a hand in violence against another,” Connie reiterated, again with the upraised fist of forcefulness. “Unless you’re going to count the Battle of the Pretenders.”

“Or the Flaming Disagreement,” Frank said.

“Or the Pantsing of Fain’s Firth.”

“Or the Castle-Whacking Unpleasantness.”

“Or O’Toole’s Tools of Terror.”

“Or the War of the Noses.”

They went on like this for quite a while. And Mack began to wonder if the fairies were exaggerating their peacefulness.

“Or the Frightful Fruit Fight.”5

“Or Little Dora’s Comeuppance.”

Finally, after about ten minutes, they ran out of wars, skirmishes, misunderstandings, slaughters, backstabbings, and murdering peaces, and Connie got back to her main theme, which was, “Aside from those few6 minor matters, no fairy has ever raised a hand in violence against another.”

Fist for emphasis.

“Until . . . ,” Frank interjected with great drama and a dramatic flourish of his wand.

“Until William MacGuffin stole the Key and used it to take sides with the fairies of clan Gorse against clan Begonia.”

A strangled sound—much like a high-pitched human voice coming from inside a flower—came from the giant sunflower. Lacking lips, tongue, or teeth, Dietmar had a hard time expressing himself clearly, but it was something like, “See! I told you so. Those are flower names!”

Mack ignored him and waited for Connie to finish her story.

The crows looked speculatively, wondering if they could make a quick in-and-out dash. Some seeds, maybe a little eyeball . . .

“MacGuffin wanted gold, and as you know, fairies have plenty of it,” Connie said. “So for thirty pieces of gold MacGuffin gave the Gorse King new and more dangerous Vargran curses. Curses that gave the Gorse King power over the Begonias and our beloved All-Mother.”

“Is there any way we can hurry this along?” Jarrah complained. “I’m beginning to regret we didn’t eat those ice-cream bars ourselves.”

“MacGuffin helped the Gorse to formulate a terrible, terrible curse.” Connie made an interesting move here, jabbing her hands forward away from her mouth, like stabbing finger-tongues. “It was a curse that caused a hideous rash in the form of rose thorns to grow in the sensitive parts of a fairy body.”

“Yeesh,” Mack said, and winced.

“Ah,” Xiao said, nodding her head almost as smugly as Dietmar sometimes did. “Hence the name Blisterthöng.”

“For a thousand years we of clan Begonia have thirsted after his blood so that we might have our revenge,” Frank said, shaking his little peace-loving fist and baring his sharp peace-loving teeth.

“Because of your peaceful nature and all,” Mack said dryly. “We thought MacGuffin was dead. It’s been a thousand years.”

“No, he’s not dead. He’s concealed by a powerful spell of the Gorse King. His castle is invisible to human eyes. Only those with the enlightened puissance—and few humans possess it—can see him or his castle.”

“That’s why you need us.”

“Yes, Mack of the Magnifica. You and these others—but not you,” Frank said, pointing out Stefan, who shuffled in embarrassment, “possess the enlightened puissance. I can make it possible for you to see the Concealed Castle of MacGuffin. And I can make it possible for you to see the All-Mother, whom only a few have seen before. And even fewer have photographed. You must take the Key from MacGuffin. And you must swear to free the All-Mother from the Gorse King’s spell.”

“Wait, I’m losing track,” Jarrah said. “This All-Mother of yours has the Blisterthöng rash?”

The fairies looked at her like she was an idiot. Which Mack thought was unfair since he had wondered the same thing.

“No. Duh,” Frank said. “She’s trapped in the body of a sea serpent.”

It took a moment for the reality to percolate up through Mack’s brain. Don’t blame him for being a little slow. He was very bright, and very attentive, but already the day had involved near death-by-car-accident and a vanful of fairies. So if he was a little slow, hey, give him a break.

“Are you talking about the Loch Ness monster?” Mack asked.

Frank bridled a bit at that, unfurled his wings, and rose a few feet into the air. “She is Eimhur Ceana Una Mordag, All-Mother to clan Begonia, as well as Beloved of the Gods, the Ultimate Warrioress, and a past holder of the record for longest sustained note on the bagpipes—they say many who heard were driven mad.” Then he settled himself down and, with a shrug, said, “But yes, most know her as the Loch Ness monster.”

“Well then,” Jarrah said briskly, “magic castle, some old dead fart who makes fairies get rashes, and the Loch Ness monster: all in a day’s work.”

Darmowy fragment się skończył.