Czytaj książkę: «Zonal Marking»

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollins 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Michael Cox 2019

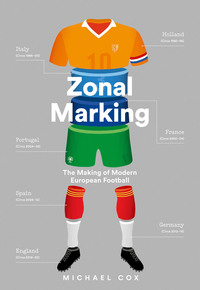

Cover layout design Sim Greenaway © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Michael Cox asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008291167

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008291150

Version: 2019-05-07

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Contents

5 Introduction

6 Part One – Voetbal, 1992–96

7 1 Individual versus Collective

8 2 Space

9 3 Playing Out from the Back

10 Transition: Netherlands–Italy

11 Part Two – Calcio, 1996–2000

12 4 Flexibility

13 5 The Third Attacker

14 6 Catenaccio

15 Transition: Italy–France

16 Part Three – Foot, 2000–04

17 7 Speed

18 8 The Number 10

19 9 The Water Carrier

20 Transition: France–Portugal

21 Part Four – Futebol, 2004–08

22 10 Structure

23 11 The First Port of Call

24 12 Wingers

25 Transition: Portugal–Spain

26 Part Five – Fútbol, 2008–12

27 13 Tiki-taka

28 14 False 9s & Argentines

29 15 El Clásico

30 Transition: Spain–Germany

31 Part Six – Fußball, 2012–16

32 16 Verticality

33 17 Gegenpressing

34 18 Reinvention

35 Transition: Germany–England

36 Part Seven – Football, 2016–20

37 19 The Mixer

38 Epilogue

39 Bibliography

40 Acknowledgements

41 List of Searchable Terms

42 Also by Michael Cox

43 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivviiviiiix134567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738394041424344454647484950515253545556575859616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315317319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367368369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383385387388389390391392393394395396397398399400401402403404405406407408409410411412413414415416417418419420421422423424425426427428429430431432433434435436ii

Introduction

Despite this book’s chronological nature, it was not originally intended to be a history of modern European football. The primary intention was to analyse the various playing styles that dominate Europe’s seven most influential footballing countries – the Netherlands, Italy, France, Portugal, Spain, Germany and England – a fairly unarguable septet, based on a combination of recent international performance and the current strength of their domestic leagues.

A nation’s footballing style is reflected in various ways. It’s not simply about the national side’s characteristics, but about the approach of its dominant clubs, the nature of its star players and the philosophy of its coaches. It’s about the experiences of a country’s players when moving abroad, and about the success of its imports. It’s about how referees officiate and what the supporters cheer. That’s what this book was always going to be about.

But then came the issue of structure – in which order should the countries be covered? Geographically? Thematically? By drawing balls out of bowls at UEFA’s headquarters? It immediately became clear that the story wasn’t simply about the different style of each country. It was also about how Europe’s dominant football country, and dominant style, had changed so regularly.

1992 was the obvious start date, heralding the back-pass law, the rebranding of the European Cup to Champions League and the formation of the Premier League. From that point, each country could be covered in turn, by focusing on a four-year period of success.

In the early 1990s the Dutch footballing philosophy was worshipped across the continent, but its influence declined after the Bosman ruling. The baton passed to Italy, which clearly boasted Europe’s strongest league. But then France started winning everything at international level and its national academy became the template for others, before suddenly, almost out of nowhere, Europe’s most revered player and manager both hailed from Portugal. Next, Barcelona and Spain won across the board during a very obvious four-year period of dominance, before tiki-taka’s decline meant Bayern and Germany took control. Finally, Europe’s most successful coaches found themselves competing in England, introducing various styles to the Premier League.

Naturally, each section strays outside these four-year boundaries. You can’t analyse Dutch football in the mid-1990s without relating it back to the Total Football of the 1970s, and you can’t analyse Didier Deschamps’ performances for France at the turn of the century without noting that he won the World Cup as manager in 2018. None of the chapters are named after specific individuals or teams from each period; they’re based around more general concepts that have been reflected in each nation’s football over a longer period.

The seven sections are different in style. The Netherlands section is about how the Dutch dictated the nature of modern European football, the Italy section focuses on specific tactical debates and the France section is about its production of certain types of player. The Portugal section is about its evolution into a serious footballing force, the Spain section about its commitment to a specific philosophy, the Germany section about its reinvention and the England section about how it borrows concepts from elsewhere.

By virtue of the book’s structure, some noteworthy teams aren’t covered extensively here: there are only passing mentions of Greece’s shock Euro 2004 triumph, Italy’s World Cup success two years later and Real Madrid’s Champions League-winning sides of recent years. But the most influential players, coaches and teams since 1992 feature heavily, and therefore, while it wasn’t the original intention, this book hopefully serves as a history of modern European football by outlining its crucial innovations, including gegenpressing, playing out from the back, tactical periodisation, tiki-taka and, of course, zonal marking.

Part One

1

Individual versus Collective

At the start of football’s modern era in the summer of 1992, Europe’s dominant nation was the Netherlands. The European Cup had just been lifted by a Barcelona side led by Johan Cruyff, the epitome of the Dutch school of Total Football, while Ajax had won the European Cup Winners’ Cup. And there was strength in depth domestically – PSV had won the league, Feyenoord won the cup.

Holland failed to retain the European Championship, having won it in 1988, but played exciting, free-flowing fotball at an otherwise disappointingly defensive Euro 92, the last tournament before the back-pass change. Europe’s most dominant player was also a Dutchman – that year’s Ballon d’Or was won by Marco van Basten, while his strike partner at international level, Dennis Bergkamp, finished third.

But the Dutch dominance wasn’t about specific teams or individuals; it was about a particular philosophy, and Dutch sides – or those coached by Dutch managers like Cruyff – promoted this approach so successfully that football’s modern era would be considered in relation to the classic Dutch interpretation of the game.

When Total Football revolutionised the sport during the 1970s, the nature of the approach was widely associated with the nature of Amsterdam. The Dutch capital was the centre of European liberalism, a mecca for hippies from all across the continent, and that was reflected in Dutch football. Ajax and Holland players supposedly had no positional responsibilities, and were seemingly allowed to wander wherever they pleased to create vibrant, free-flowing, beautiful football.

But in reality the Dutch approach was heavily systematised – players interchanged positions exclusively in vertical lines up and down the pitch, and if a defender charged into attack, a midfielder and forward were compelled to drop back and cover. In that respect, while players were theoretically granted freedom to roam, in practice they were constantly thinking about their duties in response to the actions of others. In an era when attackers from other European nations were often granted free roles, Ajax and Holland’s forwards were constrained by managerial guidelines. Arrigo Sacchi, the great AC Milan manager of the late 1980s, explained it concisely: ‘There has only been one real tactical revolution, and it happened when football shifted from an individual to a collective game,’ he declared. ‘It happened with Ajax.’ Since that time, Dutch football has held an ongoing philosophical debate – should football be individualistic like the stereotypical depiction of Dutch culture, or be systematised like the classic Total Football sides?

During the mid-1990s, this debate was epitomised by the rivalry between Johan Cruyff, the golden boy of Total Football now coaching Barcelona, and Ajax manager Louis van Gaal, who enjoyed a more prosaic route to the top. Both promoted the classic Ajax model in terms of ball possession and formation, but whereas Cruyff wholeheartedly believed in indulging superstars, Van Gaal relentlessly emphasised the importance of the collective. ‘Van Gaal works even more structurally than Cruyff did,’ observed their shared mentor Rinus Michels, who had taken charge of those legendary Ajax and Holland sides in the 1970s. ‘There is less room in Van Gaal’s approach for opportunism and changes in positions. On the other hand, build-up play is perfected to the smallest detail.’

The Dutch interpretation of leadership is somewhat complex. The Dutch take pride in their openness and capacity for discussion, which in a footballing context means players sometimes enjoy influence over issues that, elsewhere, would be the responsibility of the coach. For example, Cruyff sensationally left Ajax for Barcelona in 1973 because Ajax employed a system in which the players elected the club captain, and was so offended when voted out that he decamped to the Camp Nou. When you consider Cruyff’s subsequent impact at Barcelona, it was a seismic decision, and one that owed everything to classic Dutch principles.

Dutch players are accustomed to exerting an influence on their manager, and helping to formulate tactical plans. As Van Gaal explained of the Ajax system, ‘We teach players to read the game, we teach them to be like coaches … coaches and players alike, we argue and discuss and above all, communicate. If the opposition’s coach comes up with a good tactic, the players look and find a solution.’ While in many other countries, players instinctively follow the manager’s instructions, a team of Dutch players may offer eleven different opinions on the optimum tactical approach, which partly explains why the national side are renowned for constantly squabbling at tournaments – they’ve always been encouraged to articulate tactical ideas. This inevitably leads to disagreements, and players in the national side only ever seem to agree when they decide to overthrow the coach.

Michels, the father of Total Football, actively encouraged dissent with his so-called ‘conflict model’, which involved him luring players into dressing-room arguments. ‘I sometimes deliberately used a strategy of confrontation,’ he admitted after his retirement. ‘My objective was to create a field of tension, and improve the team spirit.’ Crucially, Michels acknowledges he always picked on ‘key players’, and when a nation’s most celebrated manager admits to provoking his best players into arguments, it’s hardly surprising that those in future generations saw nothing wrong with squabbling.

This emphasis on voicing opinions means Dutch players are often considered arrogant by outsiders, and this is another concept linked to the nature of Amsterdam. The original Total Footballers of the 1970s Ajax team were described by Cruyff as being ‘Amsterdammers by nature’, the type of thing best understood by his compatriots. Ruud Krol, that side’s outstanding defender, outlined it further: ‘We had a way of playing that was very Amsterdam – arrogant, but not really arrogant, the whole way of showing off and putting down the other team, showing we were better than them.’ Dennis Bergkamp, on the other hand, claims it is simply ‘not allowed to be big-headed in the Netherlands’, and describes the notoriously self-confident Cruyff as ‘not arrogant – it’s just a Dutch thing, an Amsterdam thing.’

Van Gaal was arguably even more arrogant than Cruyff, and was so frequently described as ‘pig-headed’ that critics sometimes appeared to be making a physical comparison. Upon Van Gaal’s appointment as Ajax boss he told the board: ‘Congratulations for appointing the best manager in the world,’ while at his first press conference, chairman Ton Harmsen introduced him with the words, ‘Louis is damned arrogant, and we like arrogant people here.’ Van Gaal was another who linked Ajax’s approach to the city. ‘The Ajax model has something to do with our mentality, the arrogance of the capital city, and the discipline of the small Netherlands,’ he said. Everyone in Amsterdam acknowledges their collective arrogance, but no one seems to admit to individual arrogance, which rather underlines the confusion.

His long-time rival, Cruyff, was arrogant for a reason: he was the greatest footballer of the 1970s and the greatest Dutch footballer ever. His career was littered with successes: most notably three Ballons d’Or and three straight European Cups. He also won six league titles with Ajax, then moved to Barcelona and won La Liga, spent some time in the United States before returning to Ajax to win another two league titles. In 1983, when not offered a new contract at Ajax, he took revenge by moving to arch-enemies Feyenoord for one final year, won the league title, was voted Dutch Footballer of the Year, and then announced his retirement. Cruyff did what he pleased and got what he wanted, enjoying all this incredible success while simultaneously claiming that success was less important than style. He personified Total Football, which made his status – as the only true individual in an otherwise very collective team – somewhat curious. He was a popular choice as Ajax manager in 1985, just a year after his playing retirement. He won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1987 and inevitably headed to another hero’s welcome in Barcelona, where he won the Cup Winners’ Cup again in 1989, then Barca’s first-ever European Cup in 1992 and their first-ever run of four straight league titles. A legendary player had become a legendary coach.

In stark contrast, when Van Gaal was appointed Ajax manager in 1991 after several disappointing post-Cruyff managerial reigns, supporters were unhappy. Cruyff had been heavily linked with a return and Ajax fans chanted his name at Van Gaal’s early matches, while De Telegraaf, the Netherlands’ biggest-selling newspaper, led a campaign calling for Cruyff’s return. Some believed Van Gaal was merely a temporary solution until Cruyff’s homecoming was secured, so it would be understandable if Van Gaal harboured resentment towards him based on those rumours. In fact, the tensions had their origins two decades earlier.

Van Gaal was a relatively talented footballer, a tall and immobile player who started up front, more playmaker than goalscorer, and later dropped back into midfield. He enjoyed a decent career, primarily with Sparta Rotterdam, but considered his playing career something of a disappointment, mainly because he had expected to become an Ajax regular. He’d joined his hometown club in 1972 at the age of 20 and regularly appeared for the reserve side, but he failed to make a single first-team appearance before being sold. The player in his position, of course, was Cruyff, and therefore Van Gaal’s entire Ajax career was spent in Cruyff’s shadow: first as his understudy when a player, then unpopular second-choice as coach.

By the early 1990s Cruyff was Barcelona manager and Van Gaal was Ajax manager, and the two were not friends. ‘We have bad chemistry,’ Cruyff confirmed. Initially, as coaches, they’d been on good terms. In 1989, when Van Gaal was Ajax’s assistant coach, he studied at a coaching course in Barcelona over Christmas and spent many evenings at the Cruyff family home, getting along particularly well with Cruyff’s son Jordi, then a Barca youth player. This, however, is supposedly where things turned sour. Van Gaal received a phone call from the Netherlands, bringing the news that his sister was gravely ill, and he rushed back to Amsterdam to see her before she died. Much later, Van Gaal suggested Cruyff was angry with him for leaving without thanking the Cruyffs for their hospitality, something Cruyff strongly denies, claiming they had a friendly encounter shortly afterwards in Amsterdam. It seems implausible that Cruyff would use Van Gaal’s tragic news to start a feud, and more likely that there was a misunderstanding at a moment when Van Gaal was emotional. But the truth is probably much simpler: this was a clash of footballing philosophies, and a clash of egos.

Cruyff devoted a considerable amount of time to winding up Van Gaal, while increasingly becoming wound up himself. By 1992 journalists were inevitably comparing Cruyff’s Barcelona to Van Gaal’s Ajax, the European Cup winners and the European Cup Winners’ Cup winners respectively, which prompted a furious response from Cruyff. ‘If he thinks Ajax are much better than Barcelona, then he’s riding for a fall, he’s making a big mistake,’ he blasted. ‘When you look at Ajax at the moment, you can see the quality is declining.’ He became increasingly petty. In 1993 he said he wanted Feyenoord to win the league ahead of Van Gaal’s Ajax. In 1994, when asked which teams across Europe he admired, Cruyff replied with Auxerre and Parma – the two sides that had eliminated Ajax from European competition in the previous two seasons. In February 1995, when a journalist suggested that Ajax might be stronger than Barcelona, his response was blunt: ‘Why don’t you stop talking shit?’ But Van Gaal’s Ajax demonstrated their superiority by winning the Champions League that year.

Van Gaal eternally stressed the importance of collectivism: ‘Football is a team sport, and the members of the team are therefore dependent upon each other,’ he explained. ‘If certain players do not carry out their tasks properly on the pitch, then their colleagues will suffer. This means that each player has to carry out his basic tasks to the best of his ability.’ Simple stuff, but you wouldn’t find Cruyff speaking about football in such functional, joyless language. Cruyff wanted his players to express themselves, to enjoy themselves, but for Van Gaal it was about ‘carrying out basic tasks’. When Ajax failed to win, Van Gaal would typically complain that his players ‘did not keep to the arrangement’, effectively accusing them of breaking their teammates’ trust by doing their own thing. However, Van Gaal’s sides were not about grinding out results – they would play in an extremely attack-minded, if mechanical, way. ‘I suspect I’m fonder of playing the game well, rather than winning,’ he once said.

A fine example of Van Gaal’s dislike for individualism came in 1992, when he controversially sold the exciting winger Bryan Roy, which prompted criticism from Cruyff, who complained that his rival didn’t appreciate individual brilliance. Van Gaal’s reason was intriguing; he ditched Roy because ‘he did not mind running for the team, but he could not think for the team’. He was hardly the first autocratic manager to become frustrated with an inconsistent winger, but whereas others eschewed them entirely in favour of narrow systems, Ajax’s approach depended heavily on width, and Van Gaal needed two outright wingers.

Left-sided Marc Overmars and right-sided Finidi George were given strict instructions not to attempt dribbles past multiple opponents: in one-against-one situations they could beat their man, but if faced with two defenders they were told to turn inside and switch the play. Ajax supporters, accustomed to wingers providing unpredictability and excitement, were frustrated by their lack of freedom, as were the players themselves. Finidi eventually left for Real Betis, where he spoke of his delight at finally being able to express himself. Van Gaal, though, hated dribbling; not only did he consider it inefficient, he thought it was the ultimate example of a footballer playing for himself. ‘We live in a laissez-faire society,’ said Van Gaal. ‘But in a team, you need discipline.’

Van Gaal’s schoolmasterly approach was entirely natural considering he’d juggled his playing career with teaching for 12 years, following in the footsteps of his hero Michels, who was also a schoolteacher. Van Gaal was by all accounts a hard taskmaster who worked in a tough school with difficult pupils, often from poor backgrounds, and this shaped his managerial philosophy. ‘Players are really just like big children, so there really is a resemblance between being a teacher and being a coach,’ he said. ‘You approach students in a certain way, based on a particular philosophy, and you do so with football players in exactly the same manner. Both at school and in a football team you encounter a pecking order and different cultures.’ Before becoming Ajax’s first-team coach, Van Gaal took charge of the club’s youth system, where he coached an outstanding group featuring the likes of Edgar Davids, Clarence Seedorf and Patrick Kluivert. This, rather than managing a smaller Eredivisie club, served as his bridge between being a teacher and becoming a first-team coach. He enjoyed working with youngsters precisely because they were malleable; once a footballer was 25, Van Gaal believed, he could no longer change their identity. The only veterans in Ajax’s 1995 Champions League-winning side were defenders Danny Blind, in his ninth year at the club, and the returning Frank Rijkaard, who had initially risen through the club’s academy in the 1980s. Van Gaal wouldn’t have countenanced signing a fully formed, non-Ajax-schooled superstar, even if they were individually superior to an existing option. ‘I don’t need the eleven best,’ Van Gaal said. ‘I need the best eleven.’

Whereas Van Gaal was a teacher, Cruyff wasn’t even a student. He’d been appointed Ajax manager in 1985 despite lacking the requisite coaching badges: Cruyff was Cruyff, and so, as always, an exception was made. And whereas Van Gaal was highly suspicious of individuals, Cruyff was delighted to indulge superstars, and his Barcelona side featured far more individual brilliance in the final third because he could, at various stages, count on four of the most revered superstars of this era: Michael Laudrup, Hristo Stoichkov, Romario and Gheorghe Hagi. The rise and fall of Cruyff’s Barcelona depended largely on his treatment of these players.

The most fascinating individual was Laudrup, effectively the Cruyff figure in Cruyff’s Dream Team. Cruyff had been his childhood hero, and at World Cup 1986, a tournament for which Holland failed to qualify, Laudrup was the outstanding player in the fabulous ‘Danish Dynamite’ side that drew comparisons to the Dutch Total Footballers of the 1970s. Laudrup signed for Barca in 1989 and immediately became the side’s technical leader, dropping deep from a centre-forward role to encourage midfield runners into attack. He could play killer through-balls with either foot, and possessed an uncanny ability to poke no-look passes with the outside of his right foot while moving to his left, leaving defenders bamboozled. He would finish his career, incidentally, with a one-year stint at Ajax in 1997/98.

On one hand, Cruyff adored Laudrup’s natural talent. When Laudrup scored a stupendous last-minute equaliser at Real Burgos in 1991/92, flicking the ball up with his left foot and smashing it into the top-right corner with his right, Laudrup rushed over to celebrate with a delighted Cruyff, among the warmest embraces between player and manager you’ll witness. But Cruyff also labelled him ‘one of the most difficult players I’ve worked with’, believing that Laudrup didn’t push his talents hard enough, and he constantly complained about his lack of leadership skills. Cruyff used Michels’s ‘conflict’ approach, but it only served to annoy the Dane, who was a nervous, reserved footballer requiring more delicate treatment.

The beneficiary of Laudrup’s measured through-balls was another supremely talented superstar, Bulgarian legend Stoichkov. ‘From more than 100 goals I scored, I’m sure that over 50 were assisted by Michael,’ Stoichkov said of his period at Barca. ‘To play with him was extremely easy – we found each other by intuition.’ That was a telling description; in a Van Gaal side attacking was about pre-determined moves, in a Cruyff side it was about organic relationships.

Like Laudrup, Stoichkov idolised Cruyff and still owned videos of the Dutchman when he agreed to join him at Barcelona, but he was completely different from Laudrup in terms of personality: aggressive, fiery and unpredictable. He’d been handed a lifelong ban from football in his homeland, later reduced to a year, for fighting at the 1985 Bulgarian Cup Final. After impressing Cruyff by scoring a wonderful chip over the head of Barcelona goalkeeper Andoni Zubizarreta for CSKA Sofia in the Cup Winners’ Cup, he arrived at the Camp Nou in 1989. ‘He had speed, finishing and character,’ Cruyff remembered. ‘We had too many nice guys, we needed someone like him.’ But in Stoichkov’s first Clásico he was shown a red card, stamped on the referee’s foot on his way off and was handed a ten-week ban. At another club Stoichkov might have been sacked, but Cruyff kept faith and he scored the winner on his return, then the following week scored four in a 6–0 victory at Athletic Bilbao. Stoichkov was worth indulging, even if he received ten red cards while at Barca, an incredible tally for a forward.

Unlike Laudrup, Stoichkov was well suited to Cruyff’s ‘conflict model’, perfectly understanding the purpose of his manager’s attacks. ‘In front of the group he told me that I was a disaster, that I wasn’t going to play the next game and that he was going to sell me,’ Stoichkov explained. ‘But at the end of training we would go and eat together.’ He repeatedly professed his hatred for Real Madrid, and supporters loved his attitude – Stoichkov would refuse to sign autographs, yet fans would just laugh at his anarchic nature. ‘He shook things up,’ said Zubizarreta. ‘Although he sometimes went too far, I am grateful for people like him who are capable of breaking the monotony of everyday life.’

Yet by 1993/94, when Cruyff won his final league title, Stoichkov wasn’t even the most arrogant forward at Barcelona, because Cruyff had raided Ajax’s rivals PSV to sign Brazilian striker Romario, an extraordinary talent who also had a reputation for skipping training sessions. ‘People say he’s a very difficult individual,’ suggested a journalist upon Romario’s arrival. ‘You could say the same thing about me,’ Cruyff fired back, delighted to sign a footballer who possessed his individualistic nature. Romario declared himself the world’s best-ever striker, announced he would score 30 league goals (he did, winning the Pichichi Trophy as La Liga’s top goalscorer), then spent the season promising that the 1994 World Cup would be ‘Romario’s tournament’ (it was, and he was then voted World Player of the Year). Whereas at PSV Romario was regularly involved in build-up play, at Barcelona he would vanish for long periods before providing a ruthless, decisive finish. His acceleration was incredible, he had a knack of surprising goalkeepers with toe-poked finishes and he unashamedly celebrated goals solo, even when he’d simply converted into a gaping net after a teammate had done the hard work.