Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

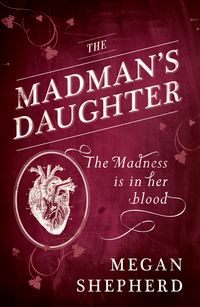

Czytaj książkę: «The Madman’s Daughter»

MEGAN SHEPHERD

The Madman’s Daughter

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

To Jesse – I love you, madly.

ONE

The basement hallways in King’s College of Medical Research were dark, even in the daytime.

At night they were like a grave.

Rats crawled through corridors that dripped with cold perspiration. The chill in the sunken rooms kept the specimens from rotting and numbed my own flesh, too, through the worn layers of my dress. When I cleaned those rooms, late at night after the medical students had gone home to their warm beds, the sound of my hard-bristle brush echoed in the operating theater, down the twisting halls, into the storage spaces where they kept the things of nightmares. Other people’s nightmares, that is. Dead flesh and sharpened scalpels didn’t bother me. I was my father’s daughter, after all. My nightmares were made of darker things.

My brush paused against the mortar, frozen by a familiar sound from down the hall: the unwelcome tap-tap-tap of footsteps that meant Dr Hastings had stayed late. I scrubbed harder, furiously, but blood had a way of seeping into the tiles so not even hours of work could get them clean.

The footsteps came closer until they stopped right behind me.

‘How’s it coming, then, Juliet?’ His warm breath brushed the back of my neck.

Keep your eyes down, I told myself, scouring the bloodstained squares of mortar so hard that my own knuckles bled.

‘Well, Doctor.’ I kept it short, hoping he would leave, but he didn’t.

Overhead the electric bulbs snapped and clicked. I glanced at the silver tips of his shoes, so brightly polished that I could see the reflection of his balding scalp and milky eyes watching me. He wasn’t the only professor who worked late, or the only one whose gaze lingered too long on my bent-over backside. But the smell of lye and other chemicals on my clothes deterred the others. Dr Hastings seemed to relish it.

He slipped his pale fingers around my wrist. I dropped the brush in surprise. ‘Your knuckles are bleeding,’ he said, pulling me to my feet.

‘It’s the cold. It chaps my skin.’ I tried to tug my hand back, but he held firm. ‘It’s nothing.’

His eyes followed the sleeve of my muslin dress to the stained apron and frayed hem, a dress that not even my father’s poorest servants would have worn. But that was many years ago, when we lived in the big house on Belgrave Square, where my closet burst with furs and silks and soft lacy things I’d worn only once or twice, since Mother threw out the previous year’s fashions like bathwater.

That was before the scandal.

Now, men seldom looked at my clothes for long. When a girl fell from privilege, men were less interested in her ratty skirts than in what lay underneath, and Dr Hastings was no different. His eyes settled on my face. My friend Lucy told me I looked like the lead actress at the Brixton, a Frenchwoman with high cheekbones and skin pale as bone, even paler against the dark, straight hair she wore swept up in a Swiss-style chignon. I kept my own hair in a simple braid, though a few strands always managed to slip out. Dr Hastings reached up to tuck them behind my ear, his fingers rough as parchment against my temple. I cringed inside but fought to keep my face blank. Better to give no reaction so he wouldn’t be encouraged. But my shaking hands betrayed me.

Dr Hastings smiled thinly. The tip of his tongue snaked out from between his lips.

Suddenly the sound of groaning hinges made him startle. My heart pounded wildly at this chance to slip away. Mrs Bell, the lead maid, stuck her gray head through the cracked door. Her mouth curved in its perpetual frown as her beady eyes darted between the professor and me. I’d never been so glad to see her wrinkled face.

‘Juliet, out with you,’ she barked. ‘Mary’s gone and broken a lamp, and we need another set of hands.’

I stepped away from Dr Hastings, relief rolling off me like a cold sweat. My eyes met Mrs Bell’s briefly as I slipped into the hall. I knew that look. She couldn’t watch out for me all the time.

One day, she might not be there to intercede.

The moment I was free of those dark hallways, I dashed into the street toward Covent Garden as the moon hovered low over London’s skyline. The harsh wind bit at my calves through worn wool stockings as I waited for a carriage to pass. Across the street a figure stood in the lee of the big wooden bandstand’s staircase.

‘You awful creature,’ Lucy said, slipping out of the shadows. She hugged the collar of her fur coat around her long neck. Her cheeks and nose were red beneath a light sheen of French powder. ‘I’ve been waiting an hour.’

‘I’m sorry.’ I leaned in and pressed my cheek to hers. Her parents would be horrified to know she had snuck out to meet me. They had encouraged our friendship when Father was London’s most famous surgeon, but were quick to forbid her to see me after his banishment.

Luckily for me, Lucy loved to disobey.

‘They’ve had me working late all week opening up some old rooms,’ I said. ‘I’ll be cleaning cobwebs out of my hair for days.’

She pretended to pluck something distasteful from my hair and grimaced. We both laughed. ‘Honestly, I don’t know how you can stand that work, with the rats and beetles and, my God, whatever else lurks down there.’ Her blue eyes gleamed mischievously. ‘Anyway, come on. The boys are waiting.’ She snatched my hand, and we hurried across the courtyard to a redbrick building with a stone staircase. Lucy banged the horse-head knocker twice.

The door swung open, and a young man with thick chestnut hair and a fine suit appeared. He had Lucy’s same fair skin and wide-set eyes, so this must be the cousin she’d told me about. I timidly evaluated his tall forehead, the helix of his ears that projected only a hair too far from the skull. Good-looking, I concluded. He studied me wordlessly in return, in my third-hand coat, with worn elbows and frayed satin trim, that must have looked so out of place next to Lucy’s finely tailored one. But to his credit, his grin didn’t falter for a moment. She must have warned him she was bringing a street urchin and not to say anything rude.

‘Let us in, Adam,’ Lucy said, pushing past him. ‘My toes are freezing to the street.’

I slipped in behind her. Shrugging off her coat, she said, ‘Adam, this is the friend I’ve told you about. Not a penny to her name, can’t cook, but God, just look at her.’

My face went red, and I shot Lucy a withering look, but Adam only smiled. ‘Lucy’s nothing if not blunt,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry, I’m used to it. I’ve heard far worse come out of her mouth. And she’s right, at least about the last part.’

I jerked my head toward him, expecting a leer. But he was being sincere, which only left me feeling more at a loss for words.

‘Where are they?’ Lucy asked, ignoring us. A bawdy roar spilled from a back room, and Lucy grinned and headed toward the sound. I expected Adam to follow her. But his gaze found me instead. He smiled again.

Startled, I paused a second too long. This was new. No vulgar winks, no glances at my chest. I was supposed to say something pleasant. But instead I drew a breath in, like a secret I had to keep close. I knew how to handle cruelty, not kindness.

‘May I take your coat?’ he asked. I realized I had my arms wrapped tightly around my chest, though it was pleasantly warm inside the house.

I forced my arms apart and slid the coat off. ‘Thank you.’ My voice was barely audible.

We followed Lucy down the hall to a sitting room where a group of lanky medical students reclined on leather sofas, sipping glasses of honey-colored liquid. Winter examinations had just ended, and they were clearly deep into their celebration. This was the kind of thing Lucy adored – breaking up a boys’ club, drinking gin and playing cards and reveling in their shocked faces. She got away with it under the pretense of visiting her cousin, though this was a far step from the elderly aunt’s parlor where Lucy was supposed to be meeting him.

Adam stepped forward to join the crowd, laughing at something someone said. I tried to feel at ease in the unfamiliar crowd, too aware of my shabby dress and chapped hands. Smile, Mother would have whispered. You belonged among these people, once. But first I needed to gauge how drunk they were, the lay of the room, who was most likely not to laugh at my poor clothes. Analyzing, always analyzing – I couldn’t feel safe until I knew every aspect of what I was facing.

Mother had been so confident around other people, always able to talk about the church sermon that morning, about the rising price of coffee. But I’d taken after my father when it came to social situations. Awkward. Shy. More apt to study the crowd like some social experiment than to join in.

Lucy had tucked herself on the sofa between a blond-haired boy and one with a face as red as an apple. A half-empty rum bottle dangled from her graceful fingers. When she saw me hanging back in the doorway, she stood and sauntered over.

‘The sooner you find a husband,’ she growled playfully, ‘the sooner you can stop scrubbing floors. So pick one of them and say something charming.’

I swallowed. My eyes drifted to Adam. ‘Lucy, men like these don’t marry girls like me.’

‘You haven’t the faintest idea what men want. They don’t want some snobbish porridge-faced brat plucking at needlepoint all day.’

‘Yes, but I’m a maid.’

‘A temporary situation.’ She waved it away, as if my last few years of backbreaking work were nothing more than a lark. She jabbed me in the side. ‘You come from money. From class. So show a little.’

She held the bottle out to me. I wanted to tell her that sipping rum straight from a bottle wasn’t exactly showing class, but I’d only earn myself another jab.

I glanced at Adam. I’d never been good at guessing people’s feelings. I had to study their reactions instead. And in this situation, it didn’t take much to conclude I wasn’t what these men wanted, despite Lucy’s insistence.

But maybe I could pretend to be. Hesitantly, I took a sip.

The blond boy tugged Lucy to the sofa next to him. ‘You must help us end a debate, Miss Radcliffe. Cecil says the human body contains 210 bones, and I say 211.’

Lucy batted her pretty lashes. ‘Well, I’m sure I don’t know.’

I sighed and leaned into the doorframe.

The boy took her chin in his hand. ‘If you’ll be so good as to hold still, I’ll count, and we can find our answer.’ He touched a finger to her skull. ‘One.’ I rolled my eyes as the boy dropped his finger lower, to her shoulder bones. ‘Two. And three.’ His finger ran slowly, seductively, along her clavicle. ‘Four.’ Then his finger traced even lower, to the thin skin covering her breastbone. ‘Five,’ he said, so drawn out that I could smell the rum on his breath.

I cleared my throat. The other boys watched, riveted, as the boy’s finger drifted lower and lower over Lucy’s neckline. Why not just skip the pretense and grab her breast? Lucy was no better, giggling like she was enjoying it. Exasperated, I slapped his pasty hand off her chest.

The whole room went still.

‘Wait your turn, darling,’ the boy said, and they all laughed. He turned back to Lucy, holding up that ridiculous finger.

‘206,’ I said.

This got their attention. Lucy took the bottle from my hand and fell back against the leather sofa with an exasperated sigh.

‘I beg your pardon?’ the boy said.

‘206,’ I repeated, feeling my cheeks warm. ‘There are 206 bones in the body. I would think, as a medical student, you would know that.’

Lucy’s head shook at my hopelessness, but her lips cracked in a smile regardless. The blond boy’s mouth went slack.

I continued before he could think. ‘If you doubt me, tell me how many bones are in the human hand.’ The boys took no offense at my remark. On the contrary, they seemed all the more drawn to me for it. Maybe I was the kind of girl they wanted, after all.

Lucy’s only acknowledgment was an approving tip of the rum bottle in my direction.

‘I’ll take that wager,’ Adam interrupted, leveling his handsome green eyes at me.

Lucy jumped up and wrapped her arm around my shoulders. ‘Oh, good! And what’s the wager, then? I’ll not have Juliet risk her reputation for less than a kiss.’

I immediately turned red, but Adam only grinned. ‘My prize, if I am right, shall be a kiss. And if I am wrong—’

‘If you are wrong’ – I interjected, feeling reckless; I grabbed the rum from Lucy and tipped the bottle back, letting the liquid warmth chase away my insecurity – ‘you must call on me wearing a lady’s bonnet.’

He walked around the sofa and took the bottle. The confidence in his step told me he didn’t intend to lose. He set the bottle on the side table and skimmed his forefinger tantalizingly along the delicate bones in the back of my hand. I parted my lips, curling my toes to keep from jerking my hand away. This wasn’t Dr Hastings, I told myself. Adam was hardly shoving his hand down my neckline. It was just an innocent touch.

‘Twenty-four,’ he said.

I felt a triumphant swell. ‘Wrong. Twenty-seven.’ Lucy gave my leg a pinch and I remembered to smile. This was supposed to be flirtatious. Fun.

Adam’s eyes danced devilishly. ‘And how would a girl know such things?’

I straightened. ‘Whether I’m right or wrong has nothing to do with gender.’ I paused. ‘Also, I’m right.’

Adam smirked. ‘Girls don’t study science.’

My confidence faltered. I knew how many bones there were in the human hand because I was my father’s daughter. When I was a child, Father would give physiology lessons to our servant boy, Montgomery, to spite those who claimed the lower classes were incapable of learning. He considered women naturally deficient, however, so I would hide in the laboratory closet during lessons, and Montgomery would slip me books to study. But I could hardly tell these young men that. Every medical student knew the name Moreau. They would remember the scandal.

Lucy jumped to my defense. ‘Juliet knows more than the lot of you. She works in the medical building. She’s probably spent more time around cadavers than you lily spirits.’

I gritted my teeth, wishing she hadn’t told them. It was one thing to be a maid, another to clean the laboratory after their botched surgeries. But Adam arched an eyebrow, interested.

‘Is that so? Well then, I have a different wager for you, miss.’ His eyes danced with something more dangerous than a kiss. ‘I have a key to the college, and you must know your way around. Let’s find one of your skeletons and count for ourselves.’

Glances darted among the other boys like sparks in a fire. They prodded one another, goading each other on in anticipation of the idea of a clandestine trip into the bowels of the medical building.

Lucy gave me an impish shrug. ‘Why not?’

I hesitated. I’d spent enough time in those dank halls. There was a darkness there that had worked its way into the hollow spaces between my bones. A darkness that clung to the hallways like my father’s shadow, smelling of formaldehyde and his favorite apricot preserves. Tonight was supposed to be about escaping the darkness – if not in the arms of a future husband, at least in a few lighthearted moments.

I shook my head.

But the boys had made up their minds, and there was no convincing them otherwise. ‘Are you trying to get out of a kiss?’ Adam teased.

I didn’t respond. My desire for flirtation had evaporated at the mention of the university basements. But if Lucy didn’t balk at the idea of seeing a skeleton, surely I shouldn’t. I cleaned the cobwebs from their creaky bones every night. So what was holding me back?

Lucy leaned in and whispered in my ear. ‘Adam wants to impress you with how brave he is, you idiot. Swoon when you see the skeleton and fall into his arms. Men love that sort of thing.’

My stomach tightened. God, was this what normal girls did? Feign weakness? I could never imagine Mother, with all her strict morals, doing something so scandalous as slipping into forbidden hallways on a dare. But Father – he wouldn’t have hesitated. He would have been the one egging them on.

Dash it. I snatched the rum and poured the last few swallows down my throat. The boys cheered. I ignored the queasy feeling in my stomach – not from the rum, but from the thought of those dark hallways we were soon to enter.

TWO

We bundled into our coats and slipped into the cold night, crossing the Strand toward the university’s brick archway. This late only a few lanterns shone in the upper windows. The boys passed a bottle around with hushed laughter at being on school grounds after hours. I wrapped my arm around Lucy’s and tried to join the mirth, but the warmth didn’t spread below my smile. For the boys, this taste of mild scandal was titillating. They’d never known real scandal or how it could tear a person apart.

Adam led us to the side of the building, through a row of hedges to a small black door I’d used only once or twice. He unlocked it and held it open. Hesitation rooted my feet to the ground, but a gentle tug from Lucy led me inside. The door closed, plunging us into darkness broken only by the moonlight from one high window.

The hallway filled with the eerie silence of unused rooms. My hands itched for a rag and brush as a legitimate reason to be here. Coming on a lark to settle a silly wager, risking my job – it didn’t feel right.

Lucy squinted into the darkness, but I kept my eyes on the tile floor. I already knew what lay at the end of the hall.

‘Well?’ Adam asked. ‘Which way to the skeletons, Mademoiselle Guillotine?’

I started to head for the small door to the storage chambers, but a light at the opposite end of the corridor caught my eye. The operating theater. Odd; no one should have been there this late. Something about that light chilled my blood – it could only mean trouble.

‘We’re not alone,’ I said, nodding toward the door. The boys followed my gaze and grew quiet. Lucy slid off her glove and found my hand in the dark.

Adam started toward the operating theater, but I grabbed the fabric of his cuff to hold him back. The hallways were filled with the normal smells – chemicals and rotten things. Usually it didn’t bother me, but tonight it felt so overpower-ing that my head started to spin. A wave of weakness hit me and I grabbed his wrist harder.

‘Are you all right?’ he asked.

I waited a few seconds for the spell to pass. These spells were not uncommon, coming upon me suddenly, usually in the late evening, though I wasn’t about to explain their source to him. ‘The skeletons are the other way,’ I said.

‘Someone’s in the theater after hours. Whatever they’re doing, it has to be good. The skeletons can wait.’ His voice was charged. This was a game to them, I realized. If they got caught, the dean might give them a stern talking-to. I would lose my livelihood.

He cocked his head. ‘You aren’t scared, are you?’

I scowled and let go of his cuff. Of course I wasn’t scared. We made our way silently down the hall. As we approached the closed door, a sound began to gnaw at my ears. It took me back to my childhood, when I would hide outside the door to Father’s laboratory, listening, trying to imagine what was happening within before the servants chased me off.

The sound grew louder, a scrape-tap, scrape-tap. Unaccustomed to being in a laboratory, Lucy threw me a puzzled look. But I knew that sound. The scrape of scalpel on stone. A gesture surgeons made to clean the flesh from the blade between cuts.

Adam threw open the door. A half-dozen students huddled around a table in the center of the room, over which a single lamp formed an island of light. They looked up when we entered, and then after a few seconds their faces relaxed with recognition.

‘Adam, you cad, get in and close the door,’ said one of the students. He threw Lucy and me an annoyed look. ‘What are they doing here?’

‘They’ll be no trouble. Right, ladies?’ Adam raised his eyebrow, but I didn’t answer. A good part of me contemplated bolting out the door and leaving them to their sick lark. Yet I didn’t. As we drifted closer with hesitant steps, I could feel the stiffness in my bones easing, as though releasing some pent-up, slippery curiosity from between my joints.

Why were they in the operating theater after dark?

Adam peered over the surgeon’s shoulder. Their bodies blocked the table, but the metallic smell of fresh blood reached me, making my head spin. Lucy pressed a handkerchief to her mouth. Memories of my father flooded me. As a surgeon, blood had been his medium like ink to a writer. Our fortune had been built on blood, the acrid odor infused into the very bricks of our house, the clothes that we wore.

To me, blood smelled like home.

I shook away the feeling. Father left us, I reminded myself. Betrayed us. But I still couldn’t help missing him.

‘They shouldn’t be here,’ I murmured. ‘This building’s closed to students at night.’

But before Lucy could answer, the scrape of the scalpel sounded again, drawing my gaze irresistibly to the table. We stepped forward. The boys paid us little attention, except Adam, who moved aside to make room. My breath caught. On the table lay a dead rabbit, its fur white as snow and spotted with blood. Its belly had been sliced open, and several organs lay on the table. Lucy gasped and covered her eyes.

My eyes were wide. I felt vaguely sorry for the dead rabbit, but it was a far-off sort of thought, something Mother might have felt. I wasn’t naive. Dissection was a necessary part of science. It was how doctors were able to develop medicine and how surgeons saved lives. I’d only ever glimpsed dissections a handful of times – peeking through the keyhole of Father’s laboratory or cleaning up after medical students. After work, in my small room at the lodging house, I’d studied the diagrams in my father’s old copy of Longman’s Anatomical Reference, but black-and-white illustrations were a poor substitute for the real thing.

Now my eyes devoured the rabbit’s body, trying to match the fleshy bits of organ and bone to the ink diagrams I knew by heart. An urge raced through my veins to touch the striated muscle of the heart, feel the smooth length of intestine.

Lucy clutched her stomach, looking pale. I watched her curiously. I didn’t feel the need to turn away like normal ladies should. Mother had drilled into me the standards of proper young ladies, but my impulses didn’t always obey. So I had learned to hide them instead.

I looked back at the rabbit. Creeping vines of worry wound around my ankles and up my legs.

‘Something’s wrong.’

The student performing the surgery glanced up, irritated, before selecting another scalpel and returning to work.

‘Sh,’ Adam breathed in my ear. My chest tightened as my eyes darted over the rabbit. There. The rabbit’s rear foot jerked. And there. Its chest rose and fell in a quick breath. I clasped Lucy’s hand, feeling the blood rushing to the base of my skull.

My brain processed the movements disjointedly, with an odd feeling like I had seen all this before. I gasped. ‘It’s alive.’

The rabbit’s glassy eye blinked. My heart faltered. I turned to Adam, bewildered, and then back to the table, where the boys continued to operate. They ignored me, as they ignored the rabbit’s movements. Something white and hot filled my head and I gripped the edge of the table, jolting it. ‘It’s not dead!’

The surgeon turned to Adam in annoyance. ‘You’d better keep them quiet.’

‘It isn’t supposed to be alive,’ Lucy stammered, her face pale. The handkerchief slipped from her hand, falling to the floor slowly, dreamlike. ‘Why is it alive?’

‘Vivisection.’ The word came out of me like a vile thing trying to escape. ‘Dissection of living creatures.’ I took a step back, wanting nothing to do with it. Dissection was one thing. What they were doing on that table was only cruel.

‘It’s just a rabbit,’ Adam hissed. Lucy began to sway. I couldn’t tear my eyes off the operation. Had they even bothered to anesthetize it?

‘It’s against the law,’ I muttered. My pulse matched the thumps of the frightened rabbit’s still-beating heart. I looked at the placement of the organs on the table. At the equipment carefully laid out. It was all familiar to me.

Too familiar.

‘Vivisection is prohibited by the university,’ I said, louder.

‘So is having women in the operating theater,’ the surgeon said, meeting my eyes. ‘But you’re here, aren’t you?’

‘Bunch of Judys,’ a dark-haired boy said with a sneer. The others laughed, and he set down a curled paper covered with diagrams. I caught sight of the rough ink outline of a rabbit, splayed apart, incision cuts marked with dotted lines. This, too, was familiar. I snatched the paper. The boy protested but I turned my back on him. My ears roared with a warm crackling. The whole room suddenly felt distant, as though I was watching myself react. I knew this diagram. The tight handwriting. The black, dotted incision lines. From somewhere deep within, I recognized it.

Behind me, the surgeon remarked to another boy in a whisper, ‘Intestines of a flesh-toned color. Pulsing slightly, likely from an unfinished digestion. Yes – there, I see the contents moving.’

With shaking fingers I unfolded the paper’s dog-eared right corner. Initials were scrawled on the diagram: H.M. Blood rushed in my ears, drowning out the sound of the boys and the rabbit and the clicking electric light. H.M. – Henri Moreau.

My father.

Through his old diagram, these boys had resurrected my father’s ghost in the very theater where he used to teach. I was flooded with a shivering uneasiness. As a child I’d worshipped my father, and now I hated him for abandoning us. Mother had fervently denied the rumors were true, but I wondered if she just couldn’t bear to have married a monster.

Suddenly the rabbit jolted and let out a scream so unnatural that I instinctively made the sign of the cross.

‘Good lord,’ Adam said, watching with wide eyes. ‘Jones, you cad, it’s waking up!’

Jones rushed to the table, which was lined with steel blades and needles the length of my forearm. ‘I gave it the proper dose,’ he stuttered, searching through the glass vials.

The rabbit’s screams pierced my skull. I slammed my hands against the table, the paper falling to the side. ‘End this,’ I cried. ‘It’s in pain!’

Lucy sobbed. The surgeon didn’t move. Frustrated, I grabbed him by the sleeve. ‘Do something! Put it out of its misery.’

Still, none of the boys moved. As medical students, they should have been trained for any situation. But they were frozen. So I acted instead.

On the table beside me was the set of operating instruments. I wrapped my hand around the handle of the ax, normally used for separating the sternum of cadavers. I took a deep breath, focusing on the rabbit’s neck. In a movement I knew had to be fast and hard, I brought down the ax.

The rabbit’s screaming stopped.

The awful tension in my chest dripped out onto the wet floor. I stared at the ax, distantly, my brain not yet connecting it with the blood on my hands. The ax fell from my grasp, crashing to the floor. Everyone flinched.

Everyone but me.

Lucy grabbed my shoulder. ‘We’re leaving,’ she said, her voice strained. I swallowed. The diagram lay on the table, a cold reminder of my father’s hand in all this. I snatched it and whirled on the dark-haired boy.

‘Where did you get this?’ I demanded.

He only gaped.

I shook him, but the surgeon interrupted. ‘Billingsgate. The Blue Boar Inn.’ His eyes flashed to the ax on the floor. ‘There’s a doctor there.’

Lucy’s hand tightened in mine. I stared at the ax. Someone bent down to pick it up, hesitantly. Adam. Our eyes met and I saw his horror at what I’d done, and more – disgust. Lucy was wrong. He wouldn’t want to marry me. I was cold, strange, and monstrous to those boys, just like my father. No one could love a monster.