Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Born to Be Posthumous»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018 Copyright © Mark Dery 2018 Mark Dery asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work Quotations and excerpts from unpublished correspondence with John Ashbery used in this volume are copyright © 2011 John Ashbery. All rights reserved. Used by arrangement with Georges Borchardt, Inc., for the author. Illustrations and excerpts from the works of Edward Gorey are used by arrangement with the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Information on previously published material appears here. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Source ISBN: 9780008329846 Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008329822 Version: 2020-08-28

Praise for Born to Be Posthumous:

‘Edward Gorey has been granted the most remarkable biography, one I believe he could have lived with. What was the likelihood that this singular genius could be restored, with such compassion and grace, within his whole context: Balanchine, surrealism, Frank O’Hara, Lady Murasaki, et al?’

JONATHAN LETHEM

‘Edward Gorey’s ardent admirers have long known there is something about his work one can’t quite pin down. Past all reason, Mark Dery has pinned it down. A genius book about a bookish genius’

DANIEL HANDLER, author of A Series of Unfortunate Events

‘Knowing Gorey’s full story, done sparkling justice by Mark Dery, will only make you adore him more’

CAITLIN DOUGHTY, author of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

‘A devoted and highly readable biography of the illustrator who – from The Doubtful Guest to The Curious Sofa – defined and embodied a world of camp, gothic hilarity’

BEN SCHOTT, Guardian Books of the Year

‘An entertaining account of an artist who liked to be coy with anybody who dared to write about him’

New York Times

‘The best biographies are the result of a perfect match between author and subject, and it’s relatively rare when the two align perfectly. But that’s the case with Born to Be Posthumous. Dery’s book is smart, exhaustive and an absolute joy to read. He has given Gorey the biography he has long deserved’

NPR

‘Excellent and deeply researched … Dery makes a convincing case that Gorey was the true godfather of Goth, inspiring a generation of pop culture memento mori, from the IMAX-scale nightmares of Tim Burton to the travails of Lemony Snicket. Dery has set the standard for a comprehensive appraisal of his legacy’

STEVE SILBERMAN, author of Neurotribes

‘A fascinating and very enjoyable biography. Dery does an excellent job in teasing out the origins of Gorey’s style. For Gorey, as this book elegantly delineates, life was to be lived in art’

MATTHEW STURGIS, author of Oscar: A Life

‘Edward Gorey is the doubtful guest in this fine biography: a stubbornly evasive and irreducible essence, now sprawled in a tureen, now chewing on crockery, now standing with his nose to the wall’

The Atlantic

‘Born to Be Posthumous clears the dust bunnies from the shadowy corners of the House of Gorey, revealing a talent that extended far beyond the macabre faux Victoriana we remember best, and a mind unlike any other’

Vogue

For Margot Mifflin, whose wild surmise—“What about a Gorey biography?”—begat this book. Without her unwavering support, generous beyond measure, it would have remained just that: a gleam in her eye. I owe her this—and more than tongue can tell.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Introduction: A Good Mystery

CHAPTER 1: A Suspiciously Normal Childhood: Chicago, 1925–44

CHAPTER 2: Mauve Sunsets: Dugway, 1944–46

CHAPTER 3: “Terribly Intellectual and Avant-Garde and All That Jazz”: Harvard, 1946–50

CHAPTER 4: Sacred Monsters: Cambridge, 1950–53

CHAPTER 5: “Like a Captive Balloon, Motionless Between Sky and Earth”: New York, 1953

CHAPTER 6: Hobbies Odd—Ballet, the Gotham Book Mart, Silent Film, Feuillade: 1953

CHAPTER 7: Épater le Bourgeois: 1954–58

CHAPTER 8: “Working Perversely to Please Himself”: 1959–63

CHAPTER 9: Nursery Crimes— The Gashlycrumb Tinies and Other Outrages: 1963

CHAPTER 10: Worshipping in Balanchine’s Temple: 1964–67

CHAPTER 11: Mail Bonding—Collaborations: 1967–72

CHAPTER 12: Dracula: 1973–78

CHAPTER 13: Mystery!: 1979–85

CHAPTER 14: Strawberry Lane Forever: Cape Cod, 1985–2000

CHAPTER 15: Flapping Ankles, Crazed Teacups, and Other Entertainments

CHAPTER 16: “Awake in the Dark of Night Thinking Gorey Thoughts”

CHAPTER 17: The Curtain Falls

Notes

A Note on Sources

A Gorey Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Mark Dery

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

A GOOD MYSTERY

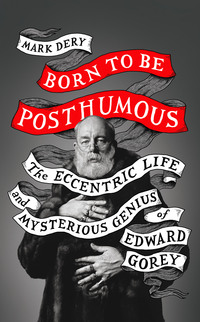

Don Bachardy, Portrait of Edward Gorey (1974), graphite on paper. (Don Bachardy and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California. Image provided by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.)

Edward Gorey was born to be posthumous. After he died, struck down by a heart attack in 2000, a joke made the rounds among his fans: During his lifetime, most people assumed he was British, Victorian, and dead. Finally, at least one of the above was true.

In fact, he was born in Chicago in 1925. And although he was an ardent Anglophile, he never traveled in England, despite passing through the place on his one trip across the pond. He was, however, intrigued by death; it was his enduring theme. He returned to it time and again in his little picture books, deadpan accounts of murder, disaster, and discreet depravity with suitably disquieting titles: The Fatal Lozenge, The Evil Garden, The Hapless Child. Children are victims, more often than not, in Gorey stories: at its christening, a baby is drowned in the baptismal font; one hollow-eyed tyke dies of ennui; another is devoured by mice. The setting is unmistakably British, an atmosphere heightened by Gorey’s insistence on British spelling; the time is vaguely Victorian, Edwardian, and Jazz Age all at once. Cars start with cranks, music squawks out of gramophones, and boater-hatted men in Eton collars knock croquet balls around the lawn while sloe-eyed vamps look on.

Gorey wrote in verse, for the most part, in a style suggestive of a weirder Edward Lear or a curiouser Lewis Carroll. His point of view is comically jaundiced; his tone a kind of high-camp macabre. And those illustrations! Drawn in the six-by-seven-inch format of the published page, they’re a marvel of pen-and-ink draftsmanship: minutely detailed renderings of cobblestoned streets, no two cobbles alike; Victorian wallpaper writhing with serpentine patterns. Gorey’s machinelike cross-hatching would have been the envy of the nineteenth-century printmaker Gustave Doré or John Tenniel, illustrator of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. Hand-drawn antique engravings is what they are.

Gorey first blipped across the cultural radar in 1959, when the literary critic Edmund Wilson introduced New Yorker readers to his work. “I find that I cannot remember to have seen a single printed word about the books of Edward Gorey,” Wilson wrote, noting that the artist “has been working quite perversely to please himself, and has created a whole little world, equally amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned.”1

That “little world” has won itself a mainstream cult (to put it oxymoronically). Millions know Gorey’s work without knowing it. Whether they noticed his name in the credits or not, Boomers and Gen-Xers who grew up with the PBS series Mystery! remember the dark whimsy of Gorey’s animated intro: the lady fainting dead away with a melodramatic wail; the sleuths tiptoeing through pea-soup fog; cocktail partiers feigning obliviousness while a stiff subsides in a lake. Then, too, every Tim Burton fan is a Gorey fan at heart. Burton owes Gorey a considerable debt, most obviously in his animated movies The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride. Likewise, the millions of kids who devoured A Series of Unfortunate Events, the young-adult mystery novels by Lemony Snicket, were seduced by a narrator whose arch persona was consciously modeled on Gorey’s. Daniel Handler—the man behind the nom de plume—calls it “the flâneur.” “When I was first writing A Series of Unfortunate Events,” he says, “I was wandering around everywhere saying, ‘I am a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey,’ and everyone said, ‘Who’s that?’ ” That was in 1999. “Now, everyone says, ‘That’s right, you are a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey!’”

Neil Gaiman’s dark-fantasy novella Coraline bears Gorey’s stamp, too. A devout fan since childhood, when he fell for Gorey’s illustrations in The Shrinking of Treehorn by Florence Parry Heide, Gaiman has an original Gorey hanging on his bedroom wall, a drawing of “children gathered around a sick bed.”2 Gaiman’s wife, the dark-cabaret singer Amanda Palmer, references Gorey’s book The Doubtful Guest in her song “Girl Anachronism”: “I don’t necessarily believe there is a cure for this / So I might join your century but only as a doubtful guest.”3

His influence is percolating out of the goth, neo-Victorian, and dark-fantasy subcultures into pop culture at large. The market for Gorey books, calendars, and gift cards is insatiable, buoying indie publishers like Pomegranate, which is resurrecting his out-of-print titles. Since his death, his work has inspired a half dozen ballets, an avant-garde jazz album, and a loosely biographical play, Gorey: The Secret Lives of Edward Gorey (2016). Of course, there’s no surer sign that you’ve arrived than a Simpsons homage. Narrated in verse, in a toffee-nosed English accent, and rendered in Gorey’s gloomy palette and spidery line, the goofy-creepy playlet “A Simpsons ‘Show’s Too Short’ Story” (2012) indicates just how deeply his work has seeped into the pop unconscious.

But the leading indicator of Gorey’s influence is his transformation into an adjective. Among critics and trend-story reporters, “Goreyesque” has become shorthand for a postmodern twist on the gothic—anything that shakes it up with a shot of black comedy, a jigger of irony, and a dash of high camp to produce something droll, disquieting, and morbidly funny.

But is that all we’re talking about when we talk about Gorey? An aesthetic? A style? The way we wear our bowler hats?

Truth to tell, we hardly know him.

Gorey’s work offers an amusingly ironic, fatalistic way of viewing the human comedy as well as a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present. Handler attributes Gorey’s enduring appeal to the sophisticated understatement and wit of his hand-cranked world, dark though it may be—a sensibility that stands in sharp contrast to the Trumpian vulgarity of our times. The Gorey “worldview—that a well-timed scathing remark might shame an uncouth person into acting better—seems worthy to me,” says Handler.

Like Handler, the steampunks and goths with Gorey tattoos who flock to the annual Edwardian Ball, “an elegant and whimsical celebration” inspired by Gorey’s work, dream of stepping into the gaslit, sepia-toned world of his stories.4 Justin Katz, who cofounded the Ball, believes revelers, many of whom come dressed in Victorian or Edwardian attire, are drawn by the promise of escape from our “Age of Anxiety,” a “chaotic time” of “accelerated media” that is “stressful and rootless” for many.

Gorey, it should be noted, groaned at being typecast as the granddaddy of the goths and would have shrunk from the embrace of neo-Victorians. “I hate being characterized,” he said. “I don’t like to read about the ‘Gorey details’ and that kind of thing.”5 There was more—much more—to the man than charming anachronisms and morbid obsessions.

Only now are art critics, scholars of children’s literature, historians of book-cover design and commercial illustration, and chroniclers of the gay experience in postwar America waking up to the fact that Gorey is a critically neglected genius. His consummately original vision—expressed in virtuosic illustrations and poetic texts but articulated with equal verve in book-jacket design, verse plays, puppet shows, and costumes and sets for ballets and Broadway productions—has earned him a place in the history of American art and letters.

Gorey was a seminal figure in the postwar revolution in children’s literature that reshaped American ideas about children and childhood. Author-illustrators such as Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, and Shel Silverstein spearheaded the movement away from the bland Fun with Dick and Jane fare of the Wonder Bread ’50s toward a more authentic representation of the hopes, anxieties, terrors, and wonders of childhood—childhood as children live it, not as the angelic age of innocence adults imagine it to be, a sentimental chromo handed down from the Victorians. Gorey was never a mass-market children’s author for the simple reason that publishers, despite his urgings, refused to market his books to children. They were squeamish about the darkness of his subject matter, not to mention the absence of anything resembling a moral in his absurdist parables.

Nonetheless, the Wednesday and Pugsley Addamses of America did read Gorey. In a nice twist, Boomer and Gen-X fans raised their children on The Gashlycrumb Tinies, turning a mock-moralistic ABC that plays the deaths of little innocents for laughs (“A is for Amy who fell down the stairs / B is for Basil assaulted by bears …”) into a bona fide children’s book. Some of those kids grew up to be cultural shakers and movers. The graphic novelist Alison Bechdel, whose scarifying tales of her childhood earned her a MacArthur “genius grant,” is a careful student of Gorey’s “illustrated masterpieces,” as she calls them; the Gorey anthology Amphigorey is among her ten favorite books.6 Following Gorey’s lead, she and others have turned traditionally juvenile genres—the comic book, the stop-motion animated movie, the young-adult novel—to adult ends, opening the door to a new honesty about the moral complexity of childhood. Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home, an unflinching exploration of growing up lesbian in the shadow of her abusive father, is only one of a host of examples.

The contemporary turn toward an aesthetic, in children’s and YA media, that is darker, more ironic, and self-consciously metatextual (that is, aware of, and often parodying, genre conventions and retro styles) would be unthinkable without Gorey. Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), a bestselling YA novel by Ransom Riggs, is typical of the genre. Unsurprisingly, it was inspired by the “Edward Gorey–like Victorian weirdness” of the antique photos Riggs collected, “haunting images of peculiar children.”7 He told the Los Angeles Times, “I was thinking maybe they could be a book, like The Gashlycrumb Tinies. Rhyming couplets about kids who had drowned. That kind of thing.”8

Gorey’s art—and highly aestheticized persona—foreshadowed some of the most influential trends of his time. His work as a cover designer and illustrator for Anchor Books in the 1950s put him at the forefront of the paperback revolution, a shift in American reading habits that, along with TV, rock ’n’ roll, the transistor radio, and the movies, helped midwife postwar pop culture. Before the Beats, before the hippies, before the Williamsburg hipster with his vest and man bun, Gorey was part of a charmed circle of gay literati at Harvard that included the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery; O’Hara’s biographer calls Gorey’s college clique “an early and elitist” premonition of countercultures to come, at a time—the late ’40s—when there was no counterculture beyond the gay demimonde.9 Though he’d shudder to hear it, Gorey was the original hipster, a truism underscored by the uncannily Goreyesque bohemians swanning around Brooklyn today in their Edwardian beards and close-cropped hairstyles—the very look Gorey sported in the ’50s.

Before retro took up permanent residence in our cultural consciousness; before the embrace, in the ’80s, of irony as a way of viewing the world; before postmodernism made it safe to like high and low culture (and to borrow, as an artist, from both); before the blurring of the distinction between kids’ media and adult media; before the mainstreaming of the gay sensibility (in the pre-Stonewall sense of a Wildean wit crossed with a tendency to treat life as art), Gorey led the way, not only in his art but in his life as well.

Yet during his lifetime the art world and literary mandarins barely deigned to notice him or, when they did, dismissed him as a minor talent. His books are little, about the size of a Pop-Tart, and rarely more than thirty pages—mere trifles, obviously, undeserving of serious scrutiny. He worked in a children’s genre, the picture book, and wrote in nonsense verse. Even more damningly, his books are funny, often wickedly so. (Tastemakers take a dim view of humor.)

But the nail in Gorey’s coffin, as far as high-culture gatekeepers were concerned, was his status as an illustrator. For much of his lifetime, critics and curators patrolled the cordon sanitaire between serious art, epitomized by abstract expressionism, and commercial art, that wasteland of kitsch and schlock. Clement Greenberg, the high priest of postwar art criticism, dismissed all representational art as kitsch; illustration, it went without saying, was beneath contempt. Decades after abstract expressionism’s heyday, the art world was still doubling down on its disdain for the genre: a 1989 article in the Christian Science Monitor noted that prominent museums were “reluctant to display or even collect” illustration art, an observation that holds true to this day.10 By the same token, graduate programs discourage dissertations on the subject because, as a source quoted in the Monitor informed, “If you choose to get involved in a secondary art form, which is where American illustration fits in, you are regarded as a secondary art historian.”

Gorey didn’t help matters by standing the logic of the critical establishment on its head. He had zero tolerance for intellectual pretension and seemed to regard gravitas as dead weight, a millstone for the mind. Like the baroque music he loved, he had an exquisite lightness of touch, both in his inked line and in his conversation, which sparkled with quips and aperçus. He pooh-poohed the search for meaning in his work (“When people are finding meaning in things—beware,” he warned) and championed as aesthetic virtues (with tongue only partly in cheek) the inconsequential, the inconclusive, and the nonchalant.11

Those virtues, as well as Gorey’s persona—a pose that incorporated elements of the aesthete, the idler, the dandy, the wit, the connoisseur of gossip, and the puckish ironist, wryly amused by life’s absurdities—were steeped in the aestheticism of Oscar Wilde and in the ennui-stricken social satire of ’20s and ’30s English novelists such as Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett, both of whom, like Wilde, were gay.

Gorey’s own sexuality was famously inscrutable. He showed little interest in the question, claiming, when interviewers pressed the question, to be asexual, by which he meant “reasonably undersexed or something,” a state of affairs he deemed “fortunate,” though why that should be fortunate only he knew.12 To nearly everyone who met him, however, his sexuality was a secret hidden in plain sight. There was the bitchy wit. The fluttery hand gestures. The flamboyant dress: floor-sweeping fur coats, pierced ears, beringed fingers, and pendants and necklaces, the more the better, jingling and jangling. And that campy delivery, plunging into sepulchral tones, then swooping into near falsetto. “Gorey’s conversation is speckled with whoops and giggles and noisy, theatrical sighs,” wrote Stephen Schiff in a New Yorker profile. “He can sustain a girlish falsetto for a very long time and then dip into a tone of clogged-sinus skepticism that’s worthy of Eve Arden.”13 Many of his intellectual passions—ballet, opera, theater, silent movies, Marlene Dietrich, Bette Davis, Gilbert and Sullivan, English novelists like E. F. Benson and Saki—were stereotypically gay. Nearly everyone who met him pegged him as such.

Viewing Gorey’s art through the lens of gay history and queer studies reveals fascinating subtexts in his work and argues persuasively for his place in gay history, situating him in an artistic continuum whose influence on American culture has been profound.

“At the heart of all of Gorey, everything is about something else,” his friend Peter Neumeyer, the literary critic, once observed.14 In his life as well as his art, he embraced opposites and straddled extremes. His tastes ranged from highbrow (Balthus, Beckett) to middlebrow (Golden Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer) to lowbrow (true-crime potboilers, Star Trek novelizations, the Friday the 13th franchise). He was equally unpredictable in his critical verdicts, pitilessly skewering dancers in George Balanchine’s ballets yet zealously defending, with a perfectly straight face, William Shatner’s animatronic acting. Allowing that his work might hark back “to the Victorian and Edwardian periods,” he pulled an abrupt about-face, asserting, “Basically I am absolutely contemporary because there is no way not to be. You’ve got to be contemporary.”15

What you saw wasn’t always what you got. Take his name. It was too perfect. Edward fits like a dream because his neo-Victorian nonsense verse is modeled, unapologetically, on that of Edward Lear (of “The Owl and the Pussycat” fame). His mock-moralistic tales are set, more often than not, in Edwardian times. Moreover, Gorey was an eternal Anglophile, and Edward is one of the most English of English names, a hardy survivor of the Norman Conquest that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times, when it was Ēadweard—“Ed Weird” to modern eyes unfamiliar with Old English, an apt sobriquet for a legendary eccentric. (Did I mention that he lived, in his later years, in a ramshackle nineteenth-century house that he shared with a family of raccoons and a poison-ivy vine creeping through a crack in the living-room wall? Gorey was benignly tolerant of both infestations—for a while.)

As for Gorey, well, the thing speaks for itself: his characters often meet messy ends. The novelist and essayist Alexander Theroux, a member of Gorey’s social circle on Cape Cod, thinks “he felt obliged to be gory-esque, G-O-R-Y, because of that name.” “Nominative determinism,” the British writer Will Self calls it.16 No doubt, the body count is high in Gorey’s oeuvre. In his first published book, The Unstrung Harp, persons unknown may have drowned in the pond at Disshiver Cottage; in The Headless Bust, the last title published during his lifetime, “crocheted gloves and knitted socks” are found on the ominously named Stranglegurgle Rocks, leading the missing person’s relatives to suspect the worst.*

Bookended by this pair of fatalities, the deaths in Gorey’s hundred or so books include homicides, suicides, parricides, the dispatching of a big black bug with an even bigger rock, murder with malice aforethought, vehicular manslaughter, crimes of passion, a pious infant carried off by illness, a witch spirited away by the Devil, at least one instance of serial killing, and a ritual sacrifice (to an insect deity worshipped by man-size mantids, no less). In keeping with the author’s unshakable fatalism, there are Acts of God: in The Hapless Child, a luckless uncle is brained by falling masonry; in The Willowdale Handcar, Wobbling Rock flattens a picnicking family.

And, of course, infanticides abound: children, in Gorey stories, are an endangered species, beaten by drug fiends, catapulted into stagnant ponds, throttled by thugs, fated to die in Dickensian squalor, or swallowed whole by the Wuggly Ump, a galumphing creature with a crocodilian grin.

To relieve the tedium between murders, there are random acts of senseless violence and whimsical mishaps:

There was a young woman named Plunnery

Who rejoiced in the practice of gunnery,

Till one day unobservant,

She blew up a servant,

And was forced to retire to a nunnery.17

Only rarely, though, does Gorey stoop to slasher-movie clichés, and then only in early works such as The Fatal Lozenge, an abecedarium whose grim limericks cross nonsense verse with the Victorian true-crime gazette. Graphic violence is the exception in Gorey’s stories. He embraced an aesthetic of knowing glances furtively exchanged or of eyes averted altogether; of banal objects that, as clues at the scene of a crime, suddenly phosphoresce with meaning; of empty rooms noisy with psychic echoes, reverberations of things that happened there, which the house remembers even if its residents do not; of rustlings in the corridor late at night and conspiratorial whispers behind cocktail napkins—an aesthetic of the inscrutable, the ambiguous, the evasive, the oblique, the insinuated, the understated, the unspoken.

Gorey believed that the deepest, most mysterious things in life are ineffable, too slippery for the crude snares of word or image. To manage the Zen-like trick of expressing the inexpressible, he suggests, we must use poetry or, better yet, silence (and its visual equivalent, empty space) to step outside language or to allude to a world beyond it. With sinister tact, he leaves the gory details to our imaginations. For Gorey, discretion is the better part of horror.

The gory details: how he detested the phrase, not least because, year after dreary year, editors repurposed that shopworn pun as a headline for profiles but chiefly because it cast his sensibility as splatter-film shtick when in fact it was just the opposite—Victorian in its repression, British in its restraint, surrealist in its dream logic, gay in its arch wit, Asian in its attention to social undercurrents and its understanding of the eloquence of the unsaid.

Gorey was an ardent admirer of Chinese and Japanese aesthetics. “Classical Japanese literature concerns very much what is left out,” he noted, adding elsewhere that he liked “to work in that way, leaving things out, being very brief.”18 His use of haikulike compression—he thought of his little books as “Victorian novels all scrunched up”19—had partly to do with a philosophical critique of the limits of language, at once Taoist and Derridean. Taoist because the opening lines of the Tao Te Ching echo his thoughts on language: “The name that can be named / is not the eternal Name. / The unnamable is the eternally real.”20 Derridean because Gorey would have agreed, intuitively, with the French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s observations on the slipperiness of language and the indeterminacy of meaning.

Gorey believed in the mutability and the inscrutability of things and in the deceptiveness of appearances. “You are a noted macabre, of sorts,” an interviewer observed, prompting Gorey to reply, “It sort of annoys me to be stuck with that. I don’t think that’s what I do exactly. I know I do it, but what I’m really doing is something else entirely. It just looks like I’m doing that.”21 Pressed to explain what, exactly, he was doing, Gorey was characteristically evasive: “I don’t know what it is I’m doing; but it’s not that, despite all evidence to the contrary.”22

It’s the closest thing to a skeleton key he ever gave us. Apply it to his work, and you can hear the tumblers click. Take death, his all-consuming obsession. Or is it? Despite the lugubrious atmosphere and morbid wit of his art and writing, Gorey uses death to talk about its opposite, life. In his determinedly frivolous way, he’s asking deep questions: What’s the meaning of existence? Is there an order to things in a godless cosmos? Do we really have free will? Gorey once observed that his “mission in life” was “to make everybody as uneasy as possible, because that’s what the world is like”—as succinct a definition of the philosopher’s role as ever there was.23

Gorey inclined naturally toward the Taoist view that philosophical dualisms hang in interdependent, yin-yang balance. And while his innate suspicion of anything resembling cant and pretension would undoubtedly have produced a pained “Oh, gawd!” if he’d dipped into one of Derrida’s notoriously impenetrable books, he had more in common with the French philosopher than he knew. Derrida, too, questioned the notion of hierarchical oppositions, using the analytical method he called deconstruction to expose the fact that, within the closed system of language, the “superior” term in such philosophical pairs exists only in contrast to its “inferior” opposite, not in any absolute sense. Or, as the Tao Te Ching puts it, “When people see some things as beautiful, / other things become ugly. / When people see some things as good, / other things become bad.”24 Better yet, as Gorey put it: “I admire work that is neither one thing nor the other, really.”25