Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Not My Idea of Heaven»

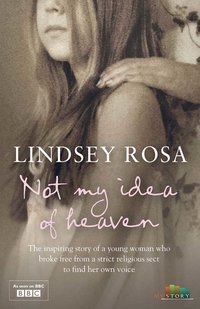

LINDSEY ROSA

Not my idea of heaven

The inspiring story of a young woman who

broke free from a strict religious sect

to find to find her own voice

I dedicate this book to my gorgeous children, Nina and Stanley; to Tom whose love has made my life worth living; to my brother who has never wavered in his support of me.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface

Chapter 1 - How Ever Did it Come to This?

Chapter 2 - Welcome to My World

Chapter 3 - One Size Fits All

Chapter 4 - The Carpenter, the Dreamer, the Romantic and Me

Chapter 5 - Motherly Love

Chapter 6 - The Ministry

Chapter 7 - School of Thought

Chapter 8 - Trouble with the Neighbours

Chapter 9 - Bound by the Rules

Chapter 10 - After Being Shut Up

Chapter 11 - The Move

Chapter 12 - Secondary Education

Chapter 13 - Coming of Age

Chapter 14 - Feeling the Strain

Chapter 15 - Reading Matters

Chapter 16 - Tailor Me, Dummy

Chapter 17 - Seafood

Chapter 18 - Camping in Gurnsey

Chapter 19 - Changing Appetites

Chapter 20 - Original Thin

Chapter 21 - Jekyll And Hyde

Chapter 22 - I Can’t Do It On My Own

Chapter 23 - So Near And Yet So Far

Chapter 24 - A Clinical Decision

Chapter 25 - Leaving Mum

Chapter 26 - Naming My Change

Chapter 27 - The Truce

Chapter 28 - Another New Life

Chapter 29 - Day Tripping

Chapter 30 - Becoming Worldly

Chapter 31 - Pleased to Meet Me

Chapter 32 - Big Girl in a Short Skirt

Chapter 33 - Living in Sin

Chapter 34 - The Baby Belly

Chapter 35 - Don’t I Want You, Baby?

Chapter 36 - Unfinished Business

Chapter 37 - And Then It Was Gone

Chapter 38 - Playing by the Rules

Chapter 39 - My Brother and Tom

Chapter 40 - Testing Times

Chapter 41 - Sister and Brother

Chapter 42 - Off the Peg

Chapter 43 - Don’t Turn Your Back on Me

Chapter 44 - Full Circle

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

The world, as we understand it, exists in our minds. The problem is, we all think differently. To some people, the world I grew up in is perfectly normal. To them, it is right, and the way the rest of the people in the world live is wrong.

How you see it depends on which side of the fence you are standing.

I was born on the wrong side of the fence. This book is about my journey from one side to the other, and how I had to leave my family behind.

Although this is a true account of my life, I have changed the names of those involved to respect their privacy as much as possible.

Chapter One

How Ever Did it Come to This?

My weight halved in a matter of months. The winter dragged by while I crouched against the radiator. I pressed my back into its heat until my skin burned. I sipped continuously from a mug of black coffee, willing the inky liquid to warm my bony body. Mum knelt in front of me, pleading, ‘Please eat.’ At last, desperate, she pushed crumbs of food into my mouth. I sealed my lips and turned my head away. Then the hunger came. I ate until I could eat no more. My belly, full of food, stretched and swelled, and I became consumed by rage. I used my fists to thump my face and jaw bone. So I sat on my hands while Mum fed me.

I became the prisoner of my mind. I listened carefully to its wild rants and became obedient to its command of weight loss. I purged my body of the pollutant, picking at my teeth to remove every last trace of food. But I wanted to be well, to be normal. How ever did it come to this?

Chapter Two

Welcome to My World

I sat in the Welfare office on the hard plastic chair behind the door. The windowless room was hot and I felt my sweaty legs sticking to the seat. The Asian boys messed around in the corner, scuffling with each other. I kept my head down and pretended to read my book. I didn’t want anyone talking to me. It was embarrassing having to be there.

Through the open door I could hear the sound of my friends singing hymns in assembly. They were Christian hymns but I didn’t recognize any of the tunes or the words. I just wanted to be with the other children, but neither their prayers nor their songs were approved by God. In my head I sang the words to a hymn that I knew would be.

Jesus bids us shine, With a pure, clear light, Like a little candle, Burning in the night In this world of darkness,

So let us shine –

You in your small corner, And I in mine.

It comforted me. On rare occasions Mum would sit at the piano and ask me what songs I wanted her to play. I’d always pick ‘Jesus Bids Us Shine’ and ‘Away in a Manger’. I stood by her elbow while she banged away at the keys and we sang together.

When the assembly was over, the Welfare lady sent us back to our classrooms to join in with the lessons. I could forget that I was different for a while, until the time for lunch came around. It was wrong to eat or drink with sinners. So I ate mine at home.

When I was old enough to read I was given a Bible. Not just any old bible: this one had my initials on the front, embossed in gold lettering. ‘L.R.M.’ The leather cover smelled expensive, not like the books Mum picked up from charity shops. This one was special.

I’d seen bibles at school, but I knew this one was different. On the first page was the name J. N. Darby. ‘What does “Translated by …” mean?’ I asked Mum.

She explained that Mr Darby was a very important man, because he had discovered the true meaning hidden in the Bible. ‘The recovery of the truth,’ she called it.

His picture stood on a shelf in our house, and had pride of place in every other home belonging to members of the Fellowship. People like us. There were other pictures too, which were also black-and-white shots of sober-looking men. These were the ‘Elect Vessels’, the men of God, chosen by Him to lead us.

We were the disciples. Those who had not discovered our truth were the ‘worldly people’.

I knew it was wrong to mix with these people, who believed in devilish things and had Satan in their hearts, but they were all around us. We lived among them, but not with them. As my Bible said, ‘Be in the world, but not of the world.’

We were special.

Special or not, I lived in a normal suburban street called Albion Avenue, lined by trees with rows of similar-looking semi-detached houses on either side. These were not Fellowship homes, they were full of worldly people, but my family somehow slotted in among them.

We were friendly enough to our neighbours. Mr and Mrs Harvey, the old couple next door, gave me and my sister Samantha chocolate treats and Mum chatted to them in the street, but our friendship ended on the doorstep.

The front garden of our house, number thirty-seven, was perhaps was a little more orderly than some of the others on the street. Mum loved gardening and took time creating neat rows of roses and irises. Other than a particularly tidy front garden there was not much to differentiate my house from any other. It all looked perfectly normal. But there was one small thing.

‘My dad says your house hasn’t got a TV aerial, so that means you haven’t got a telly,’ a boy living in my street blurted out one day.

‘No,’ I replied, ‘we don’t.’ I felt proud, he looked shocked.

‘Why not?’

I was blunt. ‘Because it’s my religion.’

‘What do you do, if you don’t watch telly?’

‘Oh, we play games,’ I said, and began the long list of exciting adventures that I got up to behind the door that was closed to all except the Fellowship.

‘I play shops and offices and …’ I could see by his face that he was becoming envious of my tremendous life. I breathed a sigh of relief; he didn’t think I was weird.

What I really did was play a lot on my own, creating an imaginary world from whatever was around me. I loved sneaking into the garage, pushing my way past the bikes and all the clutter, to find the door into the old coal cupboard where Mum kept her jam-making equipment. The shelves were stacked with jars, which I filled with potpourri and perfume, created using sticks to mash the flower petals I’d pinched from my mum’s rose garden.

My dad’s office was a wooden shed in the garden in which he designed aeroplane gearboxes for Rolls-Royce. His drawing board stood against the back wall, opposite the door. He’d roll out a huge sheet of drafting paper, tearing off lengths of masking tape to secure its corners, and begin to align his array of pencils on the parallel rule. I was fascinated with the meticulous detail in his drawings and loved watching them grow as I stood by his side, fiddling with the stationery in his desk drawer.

When Dad was out at work, I turned his office into a shop, opening the window to serve the customers. Tucked under a desk was a box of my sister’s Cindy dolls, which I’d pull out and play with on the floor. As long as I didn’t touch Dad’s drawings, I was welcome to play in there any time I liked.

Being a design engineer, Dad could turn his hand to most practical tasks. A lot of the time he spent fixing the car, but he still managed to build a go-kart for me. If he was too busy, he was more than happy to provide us with some scraps of timber from the garage, and let us make our own entertainment. Armed with some of Dad’s wood and a length of rope, my best friend Natalie and I made a crude swing, hung from a puny branch of a tree on our street. All we could do was swing one way and then the other. It was great, until the rope wore thin and snapped, and I landed on my bum.

Mum was always busy, too. She grew most of her own fruit and vegetables at the bottom of the back garden, freezing beans, and other crops, to feed us over winter. Every summer, the jam-making equipment would get dragged out of my favourite cupboard and Mum would set to work, preparing jar after jar of strawberry conserve, using the fruit we brought home from the pick-your-own farm.

How I loved spending a day there! I’d sit in the middle of the field saying, ‘One for me, one for the basket, one for me, one for the basket.’ On the way out I’d hide my face from the lady at the pay hut and try not to smile in case she saw the red stains on my cheeks and bits stuck between my teeth.

In many ways, my childhood was idyllic, but why wouldn’t it be? My family and I had been chosen by God, so, of course, life was great. I knew that, whatever happened, the six of us would always be together, Mum, Dad, Alice, Victor, Samantha and me.

Chapter Three

One Size Fits All

The Fellowship didn’t have churches with elaborate buttresses and elegant spires, just squat little meeting rooms with plain, windowless brick walls. The only way a worldly person could attend a meeting was by calling the number displayed on the board outside and making an appointment. It was very rare for anyone to do so, though. And, even if they did, they would be regarded with much suspicion. The high barbed-wire-topped fences and imposing padlocked gates were enough to put off most people.

Our meetings happened every weekday evening, once a month on Saturdays and three or four times throughout Sunday. We travelled far and wide to different meeting rooms, attending Gospel Preachings, Bible Readings, and gathering for prayer. Everyone in the Fellowship had to attend, but nobody minded. These were the great social events of our lives – the exciting part, really.

Nevertheless, they made dinnertime stressful. Dad had to make sure he was home from work on time and would usually come hurrying in, complaining about the terrible traffic on the M25. It didn’t matter that Mum had four kids to look after, her job was to ensure the dinner was on the table in good time. Stuffing down the last mouthful of his pudding, Dad would jump up and, with a flurry of goodbyes, he was gone.

I usually went to meetings only on Sundays. The first one of the day was called the Supper, held in a small meeting room just around the corner from our house. I found it strange that something that started at six a.m. could be called that. As far as I understood it, supper was the name given to the meal that people ate in the evening.

We had to wake before dawn to make sure we had enough time to prepare. It took Mum absolutely ages to get ready. Sitting on a stool in front of the big dressing-table mirror, she’d watch herself pull back strands of long brown hair, and fasten it with a clasp. She used clips to tidy up the sides, then blasted the whole lot with hairspray to keep it in place. My sister Samantha and I would watch her, fascinated, waiting for our hair to be brushed and adorned in the same way.

Once at the meeting, thirty or forty of us sat on chairs arranged in a large semicircle, and began what was known as ‘breaking bread’. The ritual involved a jug of wine and a wicker basket of bread, both of which were ceremoniously passed from person to person along the row. I always looked forward to my turn, so that I could gulp down mouthfuls of the beautifully sweet liquid, and feast myself on the doughy bread.

The lady who did the baking, Mrs Turner, had no idea that very few people actually liked her produce – no one in our Fellowship group had the heart to tell her straight. There was a detectable sense of relief in the room when she was ill and unable to bake. Personally, I loved the bread, although that was mainly because I was so hungry. None of us ate breakfast until after the meeting had finished, so, in order to satisfy our grumbling bellies, as soon as the meeting disbanded, and the parents shuffled outside into the little gravel car park to chat, the other children and I would wander through to the little kitchen and catch Mrs Turner before she tossed away her leftovers. It wouldn’t have mattered what her bread tasted like: it felt like a treat to us. With our little hands full of crusts, we would head back out through the hall, stuffing the squashed balls of dough into our mouths.

I was awakened one Sunday morning with a terrible pain ravaging my mouth. The whole of my upper lip was swollen and I was in agony. Mum had to seek permission from the Fellowship before she was allowed stay at home and look after me. It turned out I had an abscess on my tooth, but I still felt as though I had done something very wrong by missing the meeting.

‘God will understand,’ Mum reassured me. She knew more about these things than I did.

Getting to know what God understood or disapproved of was important. Somewhere in the Bible it said that a woman praying with her head uncovered puts her head to shame, and the Fellowship took this message seriously. The solution they came up with was simple. For a start, every female wore a ribbon fastened with a clip. This showed God that we were one of His, and worthy of His protection. There was still the problem of the Devil to deal with, though. As soon as we were outside our homes and meeting rooms, he could reach us. Our protection was a headscarf, and a lot of Fellowship girls were made to wear them at all times outside their homes.

I wore a headscarf to meetings, but I was spared the embarrassment of having to wear it to school or out in the street. My worldly friends may not have been allowed in the house, but I played with them in our road and didn’t want them to see me with that on my head. I told Mum, ‘I’ll wear it when I get older.’ I meant it, too. I thought that, when I reached the age of sixteen or seventeen, I would be a grownup, and when I was grown up it wouldn’t matter if I was laughed at. I suppose I thought that Fellowship adults were immune to the stares and cruel comments made by people in the big bad world. Whenever I left the house, however, I made sure I had my token in my hair. Oh, apart from that one time.

It was a summer morning and I woke up in a wonderful mood. It was just after dawn and the house was still. There were no meetings to attend and not even Mum had stirred from her slumbers. The sun was already shining and I couldn’t wait to go and play in the front garden. I dressed impatiently and brushed my hair straight in preparation for the elasticized hair band I was about to put on. Maybe it was because no one was awake to see me, I don’t know, but for some reason, on that morning, I decided to find out what it felt like to go outside with nothing in my hair.

Standing in the hallway, door open, I stared at our silent street for a moment. Then, taking in a little gasp of air, I stepped outside, beyond the safety of the house. I didn’t know what I expected to happen to me, but nothing did. So I went further, strolling down the concrete driveway, glancing left and right. I secretly wished that someone I knew would see me with my hair down, but it was too early and nobody was around. At the gate I stopped. I’d got only a few yards, but, when the realization of what I had just done hit me, I lost my nerve, dashed back into the house, closed the door, and quickly tied back my hair before anyone awoke.

Although I didn’t like wearing my headscarf in the street, I was proud to do so at the meetings, where I fitted in with all the other girls. Mum had a whole box of square head-scarves decorated with various patterns, and I hoped that one day I would have a full box just like that too. Instead, for the time being, I had to make do with my little plain lilac and pink versions. I often watched Mum carefully picking through hers, holding them up against herself to see if they matched what she was wearing.

Our clothing may have been restricted in style, but we went to town on making it as decorative as was possible within the boundaries we were set. I saw that my mum and sisters cared deeply about their appearance and knew that little details mattered a great deal to them.

Mum and Alice, who was fifteen years my senior, were always making dresses and skirts, and had become highly skilled in the art from their many years’ experience. They had little choice but to make their own, because the clothes in the shops were either too fashionable or were meant for old ladies. We certainly didn’t want to dress like old ladies, if we could help it, and fashionable usually meant too revealing. Skirts had to be respectably long – not necessarily all the way to the ankle, but definitely below the knee. A woman’s knees and shoulders could never be shown. As far as trousers were concerned, they were for men only.

I especially loved trips to the haberdashery shop, where I ran around inspecting every roll of material. The main purpose of our visits was to find some material to make into a skirt, and, if I was lucky, it would be one for me. The material I really liked would typically be colourfully decorated with sprigs of flowers and suchlike, but I usually chickened out of my first choice and went for the one that I thought would make me less conspicuous when I played in my street. Something plain. It was hard to carry off a floral dress when my worldly friends were in their jeans and T-shirts.

Sometimes Mum would ask the shop assistant to cut her a metre length of quilt stuffing, and I soon got to know what she wanted it for. Mum had developed her very own, advanced technique for getting her headscarf to sit perfectly in place. To do this, she would start by cutting the thin layer of stuffing material into the shape of a triangle. Then, laying her scarf on the bed, she’d fold it diagonally and place the stuffing on top.

It was very important that she get it positioned just right so that it wouldn’t show in the final arrangement. When satisfied with her preparations, in one flowing movement Mum would sweep the arrangement up and over in the air and flatten it down on her head, monitoring herself in the mirror as she did it. Sometimes she performed this manoeuvre five or six times before she got it just right. ‘Right’ meant no movement of the untrustworthy headscarf. I watched, impressed by her precision and attention to detail. The quilt stuffing inside stuck like glue to the layers of hairspray and packed out the scarf, making it look beautifully smooth. Next, a set of clips would go in. One last spray from the aerosol can and she was done.

No women in the Fellowship cut their hair. Mum sometimes trimmed my straggly ends and I felt – just for a few seconds – like a worldly girl. But there was no getting away from the fact I looked different. Every other girl I knew had bobbed hair or it was long but styled, whereas mine was very obviously a home job. It wasn’t that it had been done badly, only that the fashions in the eighties were so extreme. Sometimes I sat in front of Mum’s dressing table and held my long hair up so it looked as if it were short, or I pulled the ends over my head to make it look as though I had a fringe. Fringes were forbidden too, of course, as that involved cutting. It wasn’t that I especially wanted short hair or a fringe. I just would have liked the choice to have been mine.

Men had an easier time with the Fellowship’s dress code. They were forbidden from having long hair, moustaches or beards, but that hardly put them out of step with the fashions of the day. If anything, they just all looked middle-aged. On top they wore open-necked shirts, which were usually a sensible light blue or white. These were tucked into a pair of slacks cut in a classic style. It was all fairly standard stuff, but, when everything was added together, it pretty much amounted to a uniform. A worldly person would probably have trouble distinguishing a Fellowship man from a chartered accountant, but I could spot the difference a mile off !

Equality for women wasn’t exactly a priority in the Fellowship. From the top down, everything was run by men, and, as far as the Fellowship was concerned, they were chosen by God. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the meeting rooms used for Bible readings.

We all sat on tiered rows of benches, which surrounded a central stage and a single microphone on a stand. Men were seated at the front, women and children behind. The men took turns speaking into the microphone, reading from the Bible, while the women tried to pay attention. This was difficult for us girls as we rummaged in handbags, hunting for pencils and paper to scribble notes on, chatting together in loud whispers.

Women weren’t permitted to get up and speak during meetings. Their job was to announce the hymn numbers, and any woman was more than welcome to have a go at that. It meant standing up in front of everyone, and sometimes there was a long silence while the women looked at each other, hoping it didn’t have to be them. The singing was started by the men, but, if the choir lead got it wrong, we’d all end up desperately screeching at the tops of our voices.

What I loved better than wine and bread was seeing Ester and her brother Gareth. He was my age, but ‘Stelly’, as I lovingly called her, was a couple of years older. I’d often go to their house to play, while my mum and some other Fellowship women gossiped in the kitchen. One time I was running madly around their house, playing a game of hide and seek. One by one I searched all the rooms, looking in every nook and cranny. I wasn’t having any luck in the bedrooms, so I checked the loo. But when I peeked round the door and saw Gareth, I saw something else, too.

‘Hi, Lindsey,’ Gareth said.

I had never seen a boy with his trousers undone, and I revelled in my good fortune. The real ambition of a Fellowship girl was to get married and have loads of Fellowship children, and Gareth was the boy I’d already decided I’d marry when I was grown up. Now I could be certain.

That night when I said my prayers I thanked God for letting me see Gareth’s willy. He certainly worked in mysterious ways.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.