Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Declarations of War»

Cover Designer’s Note

I was too young at the time to have been aware of the historic radio broadcast by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on September 3rd, 1939, when he declared ‘…and that consequently this country is at war with Germany’. It was almost one year to the day of this announcement that our London home was demolished by enemy aircraft; we were luckier than many who suffered during the Blitz, as my parents and I were dug out of the remaining rubble, alive. Some years later I took the opportunity of using a recording of this most famous of Prime Minister Chamberlain’s speeches in one of my films on the Second World War, Genocide.

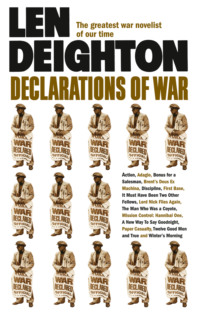

Len Deighton’s collection of short stories, Declarations of War, is a rich tapestry, illustrating scenes and landscapes from conflicts that stretch from the relatively recent Viet Nam War all the way back to the ancient days of Hannibal and the Roman Empire. As such, designing a cover for this collection presented a unique challenge: how to come up with a single image that could stand for all? In the end, it was the most obvious solution to draw upon the evocative title of the collection for inspiration; after all, what more powerful and arresting statement is there than ‘War is Announced’?

I duly searched for a photograph of a newspaper seller holding a news sheet declaring war, and eventually found an appropriate one at a photo archive. I then decided to produce a multiple of the image, each representing one of the thirteen stories, with the image on the spine representing the bonus story. The existence of a barking newspaper seller with a bundle of newspapers tucked under his arm is now something of a rarity. As such, the image captures an essence of history while communicating a message that is as potent today as it was centuries ago, announcing an event that will have a profound and devastating effect on humans on both sides of a conflict.

For the back cover I chose to photograph a montage of several objects to illustrate a few of these stories: a First World War china military ambulance bearing the crest of my home town of Margate; a US Confederate flag; a Royal Flying Corps cap badge and a cigarette card of a Battle of Britain Hawker ‘Hurricane’ fighter.

I trust that these artefacts project a flavour of the book’s content, and I hope you enjoy matching each to a story in this fine collection.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Declarations of War

Len Deighton

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This paperback edition 2010

FIRST EDITION

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1971

Copyright © Len Deighton 1985, 2010

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © JULY 2010 ISBN: 9780007395392

Version: 2017-08-18

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Cover Designer’s Note

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows

Winter’s Morning

First Base

Paper Casualty

Brent’s Deus Ex Machina

A New Way To Say Goodnight

Lord Nick Flies Again

Discipline

Mission Control: Hannibal One

Adagio

Bonus for a Salesman

Action

Twelve Good Men and True

The Man Who Was a Coyote

About the Author

By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction

Many people in the book trade dislike books of short stories, saying that readers avoid them. I believe much of this antipathy springs from the undeniable fact that most collections of short stories are a rag-bag of literary excursions, varied in quality, originating over many years and reprinted from periodicals. So I want to assure you that the stories in this volume were all written over a period of less that two years and were specifically intended for publication together here.

The basic theme of this, my only collection of short stories, is the non-heroic episodes of war; I don’t mean that these are the actions of anti-heroes (I don’t know exactly what an anti-hero is). These are stories that I planned and wrote – sometimes overlapping in their production – in a period of my life when I restlessly travelled around my mother’s country: Ireland. Ireland is a beautiful and friendly country and, armed with a portable typewriter and supported by my beloved wife, it was not a period of hardship. On the contrary, I found the changes of scene, the long stays in comfortable rural hotels, and homely Irish cooking, provided a stimulating and yet stable home for a writer.

The empty mansion that is the setting for ‘Paper Casualty’ is an enchanting location in County Louth. The description is overwritten perhaps, but the house and the grounds through which I picked my way almost every morning were as I have depicted them. Our temporary home was two big rooms plus bathroom and kitchen in the wing of a grand country house nearby. Its owners became good friends and delightful company. It was in this house and at this time that I recorded a BBC radio interview about my newly published book Bomber. Reg arrived with tape recorder in hand. Reg was a one-man band: producer, director, interviewer and technician; a free spirit. I recognized in him the same compulsive itinerancy from which I have always suffered. Perhaps that was why we hit it off so well. That evening after dinner, from talking about my research for Bomber, we talked of the war in general. Reg had served as a ‘Camp Commandant’ in an army headquarters and knew how such organizations functioned. Reg revealed the secrets of high command in a most entertaining way and, while I thought I knew quite a lot already, he provided a far more interesting insider’s view of military authority. I added the plot and used the nearby empty mansion as the setting and ‘Paper Casualty’ was born. I met Reg only once and I regret having forgotten his family name for I enjoyed his company immensely.

I have not forgotten the name of Dr David Stafford-Clark – a famous psychiatrist and author – whom I met while researching Bomber and who kept me on the straight and narrow path when I wrote ‘Brent’s Deus Ex Machina’. David had been a medical parachutist, was twice mentioned in dispatches, and had the rare experience of being the medical officer for US Eighth Air Force bombing squadrons as well as RAF ones. The role of medical officers interested me. I had always been appalled at the inhuman way that RAF operational aircrew who suffered any sort of breakdown were systematically humiliated and victimized. Combat experience, heroism and even medals did not bring exemption from such punishment. The Americans saw it differently and merely reassigned such men to ground duties. Perhaps I should have written more about the ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’ rubber-stamp designation with which the RAF ruined the life of many good, brave men. This short story only touches upon the problem and needless to say David had nothing in common with the snobbish medical officer depicted in my story.

‘A New Way to Say Goodnight’ did not have the personal input of some of the other stories. What it does have is a careful biographical background for I had no doubt that it might be scrutinized. I used many sources. While everything I have written is, to the best of my belief true, I did a selective job in order to make my point, which is: Beware! The more things change, the more they stay the same.

In 1970, a small Irish newspaper recounted the tragic Connaught Rangers mutiny that had happened half a century earlier. An eye-witness account of a British military execution is rare if not unique. I used some of this remarkable material to reconstruct the sad event in ‘Twelve Good Men and True’.

Not knowing how kind Ireland was to writers, I wasn’t brave enough to attempt a book while we were living out of suitcases. A preplanned collection of short stories, for which I would not need the overall preparation that a book requires, was clearly the way to go. It was exciting to have a chance to explore ideas that I had cosseted for ages. Obsessions with machinery and the barriers of the English class system were to the fore. Examples of pitiless authority and robotic obedience abound in our society and are the essence of tragedy. Tragedy shading into comedy can be found in the distortions of memory used in ‘It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows’ and also in ‘Action’. Such writer’s devices were not something to extend to a long book but a short dalliance with time and comprehension taught me a lot, even if much of it ended in the waste paper basket. Several of the stories consist principally of dialogue because I have always believed that descriptive material, and even action, is more powerful if it can be transcribed into dialogue. Many of my revisions – and I revise a great many times for everything I write – is devoted to converting text into dialogue.

Dialogue does not provide an easy way out. On the contrary, it brings region and class into play. And age too. Unless the story is up to date, historical syntax must be considered. Even a story set in 1940 has to respect both the subtle and shocking changes in speech since that time. When writing Bomber – a book set in 1943 – I spent many hours in the Imperial War Museum archives listening to recorded memoirs. Time spent avoiding word-use errors is time well spent. The use of modern slang in a story from ‘yesterday’ can be very disturbing to a knowledgeable reader.

There are many ways to write fiction but, as far as I recollect, I have used only three of them. There is the first-person style, in which everything is seen through the eyes of the protagonist and all the thoughts are in his head. The protagonist might be prejudiced or naïve and this method is often used for comic novels. This is the style I chose for ‘Bonus For A Salesman’. It can be powerful and direct but carries the disadvantage that the protagonist must be present; always and everywhere.

The third-person narrative avoids this restriction. The reader can be moved across the world and the writer enjoys a complete overview; a ‘cosmic’ view some call it. There is a third useful format which squeezes the advantages of both but suffers many restrictions. For this, the writer uses a third-person style but looks over the shoulder of one character to the virtual exclusion of all the others. Colonel Pelling in ‘It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows’ has his thoughts and actions described in this way.

The short story, ‘The Man Who Was A Coyote’, does not date from my time in Ireland. It is based upon research I did for MAMista, a book about South American revolution. Only after looking at the Mexican border lands, talking to people, taking photos and making notes, did I decide that MAMista’s opening chapter would be best set in the steamy jungles of South America, where the remainder of the story takes place, rather than in the USA many miles to the north. MAMista is a story about change; the way that, under pressure, enemies become friends, threats become hollow and love comes unexpectedly. The most active character is the militant, who in this short story is a coyote, a guide for illegal immigrants. I took him away from Mexico and the US Border Patrols and put him on a rusty ship nearing its destination. But I did not find it easy to forget the unreal no man’s land and the men who guard it, soldiers on a different battle ground. I went back to my research and wrote ‘Coyote’.

Writing is neither an art nor a vocation. It is neither a profession nor a trade. It is not even a job unless you stop on Friday afternoon and resume on Monday morning. Anyone who can write an honest and revealing letter, of the sort the recipient reads twice and doesn’t want to throw away, can – with thought and planning – write a short story. And a book is just a long and well-organized short story.

Len Deighton, 2010

It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows

James Sidney Pelling was fifty-nine years old. Ever since his cadet days he had been obsessed with motor-cars. He now had four: a brand-new Bentley, a battered DB6, a Land-Rover for the farm and a Cooper S that his new blower and modified carburettors would convert into the most exciting car of all.

For a job as complex as this he needed the electronic tuning bench at the Hillside Garage. They were Colonel Pelling’s tenants – he owned all the land between the farm and the Salisbury road – and the owners gave him the use of the work-shop on Sundays.

On this particular Sunday, cook had sent him sandwiches and a Thermos of coffee. He’d hardly touched them, working right through lunchtime. By three in the afternoon he was almost finished and was watching the timing on the neon strobe when a car bumped over the rubber strips that rang a bell in the office. Pelling ignored it. Anyone who failed to see the huge CLOSED notice on the pumps shouldn’t be permitted behind the wheel of a car, in Pelling’s opinion. There was the imperious toot-de-toot of an Italian power horn. It sounded again, and Pelling decided that the driver must be told to go away. He wiped his hands on a piece of cotton waste.

As he entered the cashier’s glass-fronted box, he noticed that it was raining heavily. He reached for the ancient raincoat and hat that were kept behind the door and buttoned the torn collar tight around his throat.

He could always distinguish a salesman’s car: new, cheap and fast, well-worn by heavy driving and scratched from careless parking. The driver had an expense-account plumpness. He sat behind the wheel in a drip-dry shirt, while the jacket of his shiny Dacron-mixture suit was on a hanger in the rear window. It was still swinging gently from the abrupt braking.

‘Come on, Dad,’ said the driver with a sigh.

Before Pelling could think of a reply the man was out of the car and advancing upon him, smiling the smile that only successful salesmen produce so quickly. ‘Colonel Pelling,’ he said. ‘Colonel Pelling. Well, I’ll be buggered, begging your pardon, sir.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Pelling stiffly. ‘You have the advantage of me…’

‘Wool. You can’t go wrong with me next to the skin.’ He laughed.

‘Wool?’

‘My little joke, Colonel.’ He stood to attention in a burlesque of military obedience. ‘Wool; W-o-o-l, Corporal Wool 397, sir! Royal Welsh Greys, D Squadron, No. 1 Troop. From Tunisia all the way to Florence. Best years of my life, in a way. Place me now, sir?’

Pelling tried to make this over-fed, middle-aged man into a young corporal. He failed.

‘The farmhouse on the hill,’ prompted Wool, ‘near Sergeant-Major village.’

The Colonel still looked puzzled and Wool said, ‘Oh well, it must have been two other fellows, eh?’ He laughed and repeated his joke slowly. When he spoke again his voice was loud and a little exasperated. ‘Don’t tell me you’ve forgotten the farmhouse. When the Tedeschi nearly clobbered the whole mob of us, and we sat there like lemons?’

‘Of course,’ said Pelling, ‘you were the fellow with the Bren. I remember him quite differently…’

‘No, no, no,’ said Wool. ‘That was a bloke named Stephens. He got the M.M. for that. That was the following week.’

‘Corporal Wool, yes…’

‘Lance-jack at the time, actually. Ended up a sergeant though: temporary, acting, unpaid.’ He smiled and saluted.

‘Wool,’ said Pelling. ‘It’s good to see you again. You’re looking well and prosperous.’

Wool grinned and tucked his shirt into his waistband. ‘It always comes loose when I’m driving. Yeah, well, I’m not bad, how are you?’

‘I’m well, in fact very well.’

Wool shook his head doubtfully and stared into Pelling’s face. ‘You’re not looking too good, Colonel, if you don’t mind an exlance-jack saying so.’

‘I’m just a bit tired,’ said Pelling. He smiled at Wool’s concern. ‘I’ve been working since eight o’clock this morning.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes.’

‘Christ!’ He looked around the rain-swept forecourt. It was grimy and littered with ice-cream tubs. A sign said: FREE WITH 4 GALLONS OF PETROL, A PACKET OF BALLOONS.

‘A packet of bleeding balloons,’ said Wool. ‘All these petrol companies are the same: free bloody hair-brushes or free bloody wine-glasses. What they want to offer is a free bloody service: top-up the battery, check the water and tyre pressures. I’ll bet you never wipe the windscreens, do you?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Exactly. Here,’ he grabbed at Pelling’s sleeve, ‘you own this place?’

‘I’m afraid not.’

Wool sniffed and nodded to himself. ‘It’s a rotten shame, that’s all I can say. You were the youngest-looking Colonel any of us had ever seen – a chestful of gongs, and a good bringing-up, it’s a bloody disgrace. There’s your Socialist governments for you. Here, I’m getting wet, jump in out of this rain.’ Wool reached for The Times and put two sheets of it upon the plastic seat before opening the door for Pelling.

‘Colonel Pelling,’ said Wool, looking at him closely and imprinting the memory of this moment upon his mind. ‘Colonel Pelling.’

Wool twisted round in his seat and found a packet of cheroots in his jacket. He tore off its cellophane wrapping and opened it with a flourish. ‘Have a cigar?’

‘Thank you, Wool, no. I’ve given up smoking.’

‘It’s a rich man’s hobby now,’ agreed Wool. He put the cheroots away and took from the glove compartment a Havana in a metal container. He used a cigar-cutter to prepare it, and lit it with enough ceremony to demonstrate that he was a man familiar with good living. He exhaled the smoke slowly and turned to face the ex-Colonel with a calm happiness.

The Colonel had aged well; no surplus fat or heavy jowls. His nose was bony and his jaw was hard. He was lean and tall, just as Wool remembered him, except that the hair below his oily hat was almost white. Wool looked at Pelling’s hands. His dirty skin was tanned and leathery, just as one would expect of a man who spent long hours out in all weathers slaving at the petrol pumps.

Wool, on the other hand, was not so easy to identify with the nineteen-year-old Corporal that the Colonel had briefly known. Florid, and wearing large fashionable black-framed spectacles, he was like any one of the dozens of commercials who filled up at the Hillside before the non-stop race back to London. On his finger there was a signet ring and on his wrist a complex watch and a gold identity bracelet.

It must have been two other fellows, thought Pelling. Yes, as soldiers they had been saints or hooligans, torturers or rescuers, but none survived. Those that eventually became civilians were different men.

Pelling looked at the interior of the car. No doubt about it being cherished and cared for, even if it wasn’t done to Pelling’s taste. The steering-wheel had a leather cover, the seats were covered in imitation leopard-skin and a baby’s shoe dangled from the mirror. There was a St Christopher bolted to the dashboard and in the rear window there was a large plastic dog that nodded and two cushions with the registration number boldly knitted into their design.

‘Seen any of your blokes?’ asked Wool.

‘Not recently,’ said Pelling.

‘I’ve never been to an Old Comrades or anything.’

‘Nor have I,’ said Pelling. ‘I’m not much use at that sort of thing.’

Wool looked at the filthy raincoat. ‘I understand,’ he said. He studied the ash of his cigar. ‘The funny thing was that you only came up to the farmhouse for a look-see, didn’t you?’

‘I’m only here for a shufti, Lieutenant.’ The subaltern looked at the man crawling in through the door. The newcomer’s rank badges were unmistakable, and yet he looked younger than the thirty-year-old Lieutenant. ‘You came on foot, sir?’

‘Jeeped up the wadi.’

‘Corporal. Crawl out and move the Colonel’s Jeep into the barn out of sight.’

‘There’s eight gallons of water in it for you,’ said Pelling, ‘and a crate of beer for your chaps.’

‘That will cheer them up, sir.’

‘It won’t cheer them up much,’ said Pelling. ‘It’s that gnats’-pee from Tunis. Psychological warfare by the temperance people, I’d say.’

The Lieutenant rubbed his unshaven chin and nodded his thanks as the Corporal went out into the yard and started to move the Jeep.

‘It’s stupid of me,’ said Pelling. ‘I didn’t realize they could see as far as the track.’

‘They’ve got a new O.P. on the east slope of the big tit – Point 401 that is – we only noticed it yesterday, my sergeant saw a bit of movement there. Can’t be sure it’s manned all the time.’

‘It was stupid of me,’ repeated Pelling.

The Lieutenant had seldom spoken with colonels and certainly not one who’d admit to stupidity. Awkwardly he said, ‘Would you like to go up to the loft, sir? Sloan, get brewing. And open that tin of milk.’

The Colonel held the field glasses delicately, as though he was taking the pulse of two black-metal wrists. From the loft he could see more than ten miles along the valley. It was noon. The sunbaked hills were misty green puddings, surmounted by outcrops of grey rock and ringed by precarious terraces of crops. The olive groves lower down were plagued with the black festering sores of artillery fire, and untended vegetables had run to seed. Nowhere was there any movement of man or machine, nor were there horses or mules, cattle, sheep or goats – at least, no live ones. Pelling searched carefully along the German lines from where the River Caro was no more than a piddle of dirty water meandering through the high-banked wadi, to the ruins of ‘Sergeant-Major’, as the troops had renamed the village of Santa Maria Maggiore. If it hadn’t been for the cowshed at the far end of the yard, and the abandoned Churchill tank fifty yards behind it, he’d have been able to see the hills beyond the river, and the main road that led eventually to Rome. He studied the road carefully: dust hung above it like incense smoke, and yet he could see no transport there. From somewhere far away a church bell began tolling an inexpert rhythm.

‘A dedicated priest,’ said Pelling, still looking through the glasses. Then he lowered them and began to wipe the lenses. He used a white linen handkerchief, rough-dried and unpressed and mottled with the faint stains of ancient dirt.

‘Partisans, more likely. They use the bells as signals to regroup.’ He passed the Colonel a handkerchief of khaki silk. Bought by a loving mother for a newly commissioned son, thought Pelling as he finished polishing the binoculars. Handling the smelly glasses with exaggerated care, Pelling put them into the battered leather case and gave them back to the Lieutenant.

‘Your people will be coming tomorrow, sir?’

‘Yes, we’ll get rid of that tank and cowshed for you.’ He said it like a surgeon about to amputate, and like a humane surgeon he tried to give the impression that it would make things better.

‘That will give us quite a view,’ said the Lieutenant. Pelling nodded. They both knew that it would make the farm such a good observation point that then the Germans would also want it. Very badly.

‘Our attack can’t be far off now,’ said the Lieutenant, seeking reassurance. Pelling said nothing. Allied H.Q. didn’t tell engineer colonels their plans, any more than they told infantry subalterns. They told the one to clear fields of fire and the other to shoot.

Pelling said, ‘In another three or four weeks the autumn rains will make that valley into a bog. Do you know what rain does to that dusty soil?’ It was a rhetorical question; the Lieutenant’s face, hair, hands and uniform – like everyone else’s – were coloured grey by the same abrasive powder that got in the guns and the tea.

‘Yes,’ said the Lieutenant. The attack would be soon.

What sort of man would build a farm up here on the side of Monte Nuovo: a fool or an aesthete, or both. The wind screamed constantly, the cloud was almost close enough to touch and the trees were stunted and hunchbacked; but the view was like a Francesca painting. Back in Pelling’s part of the world men built their houses low.

In war, though, it was the villages in the valleys that survived best. Houses and churches on high ground were invariably destroyed as the armies fought for observation points. There was a moral there somewhere, thought Pelling, but he was too tired to deduce it.

‘What will you do after the war, Lieutenant?’ Pelling sipped the hot sweet tea that was heavy with the smell of condensed milk.

‘Oh, I don’t know.’ This was a new sort of conversation and he spoke in a different voice and omitted the ‘sir’. ‘I always wanted to be a vet – I’m keen on animals – but I’ll be too old to start studying by the time this lot’s over. Probably I’ll just take over the old man’s antique shop. And you?’

At first the Lieutenant was afraid that he’d offended the young Colonel. With an M.C. and D.S.O. and a colonel’s rank at his age, perhaps he felt that there was no other world but the army. To soften it a little the Lieutenant said, ‘You’re a regular, of course.’

Pelling grinned, ‘Yes. Woolwich, Staff College, the lot. I’m about as regular as you can get.’

‘I suppose this is…to us it’s the worst sort of interruption to our lives, but I suppose for you it’s the thing you’ve been waiting for.’

‘All you War Service types think that,’ said Pelling, ‘but if you think that any regular soldier likes fighting wars, you’re quite wrong.’ He saw the Lieutenant glance at his badges. ‘Oh, we get promotion, but only at the expense of having our nice little club invaded by a lot of amateurs who don’t want to be there. The peacetime army is quite a different show. A chap doesn’t go into that in the hope that there will eventually be a war.’

Darmowy fragment się skończył.