Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Bomber»

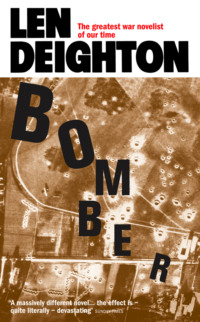

LEN DEIGHTON

Bomber

Events relating to the last flight of an RAF Bomber over Germany on the night of June 31st, 1943

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1970

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1970

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

The words from the song ‘Easy Come, Easy Go’ (composed by John Green and written by Edward Heyman; copyright 1934 by Warner Bros 7 Arts Music) are reproduced by kind permission of Chappell & Co Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780586045442

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007347728

Version: 2017-05-22

Epigraph

Ritual: A system of religious or magical ceremonies or procedures frequently with special forms of words or a special (and secret) vocabulary, and usually associated with important occasions or actions.

Dr J. Dever,

Dictionary of Psychology (Penguin Books)

Between February 1965 and July 31st, 1968, the American bombing missions in Vietnam numbered 107,700. The tonnage of bombs and rockets totalled 2,581,876.

Keisinger’s Continuous Archives

The attitude of the gallant Six Hundred which so aroused Lord Tennyson’s admiration arose from the fact that the least disposition to ask the reason why was discouraged by tricing the would-be inquirer to the triangle and flogging him into insensibility.

F. J. Veale,

Advance to Barbarism (Mitre Press, 1968)

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Map

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map

Introduction

Bomber was the first fiction book written using what is now called a ‘word processor’. In 1969 that name did not exist. It was an IBM engineer visiting my home at the Elephant and Castle in London to check my golfball typewriter, who asked me: ‘Do you know how many times your secretary has retyped this chapter?’ He waved pages in the air.

‘Half a dozen times?’ I said defensively. I knew my wonderful Australian secretary Ellenor Handley retyped chapters only when her typewritten words were almost obscured by my handwritten changes.

‘Twenty-five times,’ said the IBM man. ‘Your poor secretary!’

I tried to look repentant.

Along the street at the mighty Shell Centre, IBM had installed banks of computer-driven machines that produced printed in-house essentials such as instruction manuals.

‘Come along and see them,’ urged the IBM man. Being somewhat obsessed by machinery (while not really understanding it) I went along. Soon I became the only private individual permitted ownership of an IBM MT 72 computer. It was the size and shape of a small upright piano. I was very proud of that machine, I showed it to everyone who visited me, but it was Ellenor who mastered it.

My friend Julian Symons, the writer and doyen of critics, said I was the only person he knew who actually liked machines. ‘Perhaps you should write a book about them’, he said, only half seriously. That was the start of Bomber. Does everyone hate machines? Perhaps they do; so suppose I wrote a story in which the machines of one nation battled against the machines of another? Yes, I knew about that. I had been bombed every night for months at a time in London. The night bombing campaigns were fought in complete darkness, with both the enemy aircraft and the terrain below depicted only as tiny blips and blobs on glass screens. The combatants never saw their enemies. It had a spooky fascination for me but would such a grim mechanical theme overshadow a story’s human element?

The human element was already a difficult aspect of writing such a story. Most of the characters – both British and German – would be able-bodied young men chosen for their physical, emotional and psychological similarity. To make it more difficult, my preliminary notes showed that I would need a cast of well over a hundred of these similar young people. This meant a style that would bring a character to life in only a sentence or two of dialogue. And do it well enough for the reader to pick up on that character two or three chapters later. And I was determined to do it without resorting to crude regional pronunciations.

It was daunting. I began to talk to experts and discovered how deep I was going to have to dig for my research. German radar was very advanced by 1943; it was only after that that Anglo American technology took the lead. But the Germans lost their technical lead and lost the war too. That meant that very few people had taken any interest in the history of German air defences. I went to Germany and sought out the technicians and radar operators as well as the night-fighter pilots and Flak crews. Then I had to put their explanations together well enough to understand the basis of the German air defence system. The more I learned about it, the more it fascinated me.

If 1943 German radar controllers and night-fighter veterans were a complex challenge, then wait until I started to delve into the social life, scandals and Nazi-led politics of a small Westphalian town. Everyone seemed to have a war story. One lady found for me some striped overalls that she had made from her nurse’s uniform. A man I met in a restaurant had kept all his wartime documents and when I showed interest in them insisted that I kept them. My wife Ysabele’s fluent German was the key to this conversational research and greatly expanded the number of people and stories available to me.

It was almost overwhelming but it was too late to stop, and anyway I enjoy research. One large room of my London home was devoted entirely to Bomber. I collected everything available: films, air photos, logbooks, letters, recordings, tele-printer orders and target maps. Pasting aeronautical maps together I covered one whole wall with northern Europe. Tapes of the bomber routes, turning-points, dog-legs and feints showed each aircraft in the story. Tabs for times meant I could see where each fighter or bomber would be at any chosen moment.

The anchor of the story was to be found in England’s Bomber Command airfields. I knew many of them from my time in the RAF and I returned to see them again. My RAF veterans were great companions with anecdotes galore, and during my service years I had flown in Mosquitos and in Lancaster bombers. In Germany Adolf Galland found for me some of the best of his night fighter crews. The Dutch air force allowed me to spend some time on a military airfield that was very little changed from 1943. By amazing luck I was able to find, enter and climb around one of the very few Luftwaffe ‘Opera House’ command centres just days before its demolition began. It was a vast echoing place and by chance the demolition crews had left all the electric lights burning, probably for safety reasons. Back in London my good friends at the Imperial War Museum gave me a room filled with Luftwaffe instructional films about the night-fighter version of the Junkers Ju 88 and by bending the rules a little I also got to climb inside one.

Right from the first notes I had decided upon the twenty-four hour time format. It meant that I would describe only one RAF bombing raid but I could depict it in detail. By describing mechanical elements (such as the number of fragments into which the average anti-aircraft shell breaks) I wanted to emphasize the dehumanizing effect of mechanical warfare. I like machines but in wars all humans are their victims.

Len Deighton, 2009

Although I have attempted to make its background as real as possible this is entirely a work of fiction. As far as I know there were no Lancaster bombers named ‘Creaking Door’, ‘The Volkswagen’ or ‘Joe for King’. There was no RAF airfield named Warley Fen and no Luftwaffe base called Kroonsdijk. There was no Altgarten and there were no real people like those I have described. There was never a thirty-first day of June in 1943 or any other year.

L.D.

Chapter One

It was a bomber’s sky: dry air, wind enough to clear the smoke, cloud broken enough to recognize a few stars. The bedroom was so dark that it took Ruth Lambert a moment or so to see her husband standing at the window. ‘Are you all right, Sam?’

‘Praying to Mother Moon.’

She laughed sleepily. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘Do you think I don’t need all the witchcraft I can get?’

‘Oh, Sam. How can you say that when you …’ She stopped.

He supplied the words: ‘Have come back safe from forty-five raids?’

She nodded. He was right. She’d been afraid to say it because she did believe in witchcraft or something very like it. In an isolated house in the small hours of morning with the wind chasing the clouds across the bright moon it was difficult not to fall prey to primitive fears.

She switched on the bedside light and he shielded his eyes with his hand. Sam Lambert was a tall man of twenty-six. The necessity of wearing his tight-collared uniform had resulted in his suntan ending in a sharp line around his neck. His muscular body was pale by comparison. He ran his fingers across his untidy black hair and scratched the corner of his nose where a small scar disappeared into the wrinkles of his smile. Ruth liked him to smile but lately he seldom did.

He buttoned the yellow silk pyjamas that had cost Ruth a small fortune in Bond Street. She’d given them to him on the first night of their honeymoon; three months ago, he’d smiled then. This was the first time he’d worn them.

As the only married couple among Cohen’s guests, Ruth and Sam Lambert had been given the King Charles bedroom with tapestry and panelling so magnificent that Sam found himself speaking in whispers. ‘What a boring weekend for you, darling: bombs, bombing, and bombers.’

‘I like to listen. I’m in the RAF too, remember. Anyway we had to come. He’s one of your crew, sort of family.’

‘Yes, you’ve got half a dozen brand-new relatives.’

‘I like your crew.’ She said it tentatively, for just a few trips ago her husband had flown back with his navigator dead. They had never mentioned his name since. ‘Has the rain stopped?’ she asked.

Lambert nodded. Somewhere overhead an aeroplane crawled across the cloud trying to glimpse the ground through a gap. On a cross-country exercise, thought Lambert, they’d probably predicted a little light cirrus. It was their favourite prediction.

Ruth said, ‘Cohen is the one that was sick the first time?’

‘Not really sick, he was …’ He waved his hand.

‘I didn’t mean sick,’ said Ruth. ‘Shall I leave the light on?’

‘I’m coming back to bed. What time is it?’

‘No,’ said Ruth. ‘Only if you want to. Five-thirty, Monday morning.’

‘Next weekend we’ll go up to London and see Gone with the Wind or something.’

‘Promise?’

‘Promise. The thunderstorm has passed right over. It will be good flying weather tomorrow.’ Ruth shivered.

‘I had a letter from my dad,’ he said.

‘I recognized the writing.’

‘Can I spare another five pounds.’

‘He’ll drink it.’

‘Of course.’

‘But you’ll send it?’

‘I can’t just abandon the poor old bugger.’

There were cows too, standing very still, asleep standing up, he supposed, he knew nothing about the country. He’d hardly ever seen it until he started flying seven years ago. There was so much open country. Acres and acres young Cohen’s family had here, and a trout stream, and this old house like something from a ghost story with its creaking stairs, cold bedrooms and ancient door latches that never closed properly. He reached out and ran his fingers across the tapestry; they’d never allow you to do that in the V and A Museum.

Some of the windowpanes were discoloured and bubbly and the trees seen through them were crippled and grotesque. At night the countryside was strange and monochromatic like an old photograph. To the east, over the sea beyond Holland and Germany, the sky was lightening enough to silhouette the trees and skyline. Eight-tenths cloud, just an edge of moonlight on a rim of cumulus. You could sail a whole damned Group in over that lot, and from the ground it would be impossible to catch a glimpse of them. He turned away from the window. On the other hand they’d have you on their bloody radar.

He walked across the cold stone floor and looked down at his wife in the massive bed. Her black hair made marble of the white pillow and with her eyes tightly closed she was like some fairy princess waiting to be awoken with a magic kiss. He pulled the curtains of the ancient four-poster bed aside and it creaked as he eased his body down between the sheets. She made a sleepy mumbling sound and pulled his chilly body close.

‘He was just tense,’ said Lambert. ‘Cohen’s a bloody nice kid, a wizard damned navigator too.’

‘I love you,’ Ruth mumbled.

‘Everyone gets tense,’ explained Lambert.

His wife pulled the pillow under his head and moved to give him more room. His eyes were closed but she knew he was not sleepy. Many times at night they’d been awake together like this.

When they married in March it had rained when they arrived at the church, but as they came on to the steps the sun came out. She’d worn a pale-blue silk dress. Two other girls had married in it since then.

Her face pressed close to him and she could hear his heart beating. It was a calming, confident sound and soon she dropped off to sleep.

The one-time grandeur of the Cohens’ country house was defaced by wartime shortages of labour and material. In the breakfast room there was a damp patch on the wall and the carpet had been turned so that the worn part was under the sideboard. The small, leaded windows and the clumsy blackout fittings made the room gloomy even on a bright summer’s morning like this one.

Each of the airmen guests was already coming to terms with the return to duty and each in their different ways sensed that the day would end in combat. Lambert had smelled the change in the weather, and he chose a chair that gave him a glimpse of the sky.

The Lamberts were not the first down to breakfast. Flight Lieutenant Sweet had been up for hours. He told them that he had taken one of the horses out. ‘Mind you, all I did was sit upon the poor creature while it walked around the meadow.’ He had in fact done exactly that, but such was his self-deprecating tone that he was able to suggest that he was a horseman of great skill.

Sweet chose to sit in the Windsor hoopback armchair that was at the head of the table. He was a short, fair-haired man of twenty-two, four years younger than Lambert. Like many of the aircrew he was short and stocky. Ruddy-complexioned, his pink skin went even pinker in the sun, and when he smiled he looked like a happy bouncing baby. Some women found this irresistible. It was easy to see why he had been regarded as ‘officer material’ from the day he joined up. He had a clear, high voice, energy, enthusiasm, and an unquestioning readiness to flatter and defer to the voice of authority.

‘And an ambition to get to grips with the Hun, sir.’

‘Good show, Sweet.’

‘Goodness, sir, I can’t be any other way. That sort of thing is bred into a chap at any decent public school.’

‘Good show, Sweet.’

Temporarily Sweet had been appointed commander of B Flight’s aircraft, one of which Lambert piloted. He was anxious to be popular: he knew everyone’s nickname and remembered their birthplace. It was his great pleasure to greet people in their hometown accent. In spite of all his efforts some people hated him. Sweet couldn’t understand why.

This month the Squadron had been transferred to pathfinder duties. It meant that every crew must do a double tour of ops. Double thirty was sixty, and sixty trips over Germany, with the average five-per-cent casualty rate, was mathematically three times impossible to survive. Lambert and Sweet had already completed one tour and this was their second. Actuarily they were long since dead.

Sweet was telling a story when Flight Sergeant Digby came into the room. Digby was a thirty-two-year-old Australian bomb aimer. He was elderly by combat aircrew standards and his balding head and weathered face singled him out from the others. As did his readiness to puncture the dignity of any officer. He listened to Flight Lieutenant Sweet. Sweet was the only officer among the guests.

‘A fellow drives into a service station,’ said Sweet. His eyes crinkled into a smile and the others paid attention, for he was good at telling funny stories. Sweet knocked an edge of ash into the remains of his breakfast. ‘The driver had only got coupons for half a gallon. He says, “A good show Monty’s boys are putting on, eh?” “Who?” says the bloke in the service station, very puzzled. “General Montgomery and the Eighth Army.” “What army?” “The Eighth Army. It’s given old Rommel’s Panzers a nasty shock.” “Rommel? Who’s Rommel?” “OK,” says the bloke in the car, putting away his coupons. “Never mind all that crap. Fill her up with petrol and give me two hundred Player’s cigarettes and two bottles of whisky.”’

It was unfortunate that Sweet had cast the driver as an Australian for Digby was rather sensitive about his accent. Appreciative of the smiles, Sweet repeated the punch line in his normal voice, ‘Fill her up with petrol and give me two hundred cigarettes.’ He laughed and blew a perfect smoke ring.

‘That’s a funny accent you’re using now,’ said Digby.

‘The King’s English,’ acknowledged Sweet.

‘I hope he is,’ said Digby. ‘With a ripe pommy accent like his he’d have a terrible time back where I come from.’

Sweet smiled. Under the special circumstances of being fellow guests in Cohen’s father’s house he had to put up with a familiarity that he would never tolerate on the Squadron.

‘It’s just a matter of education,’ said Sweet, referring as much to Digby’s behaviour as to his accent.

‘That’s right,’ agreed Digby, sitting down opposite him. Digby’s tie had trapped one point of his collar so that it stood up under his jawline. ‘Seriously, though, I really admire the way you fellows speak. You can all make Daily Routine Orders sound like Shakespeare. Now, you must have been to a good school, Flight Lieutenant Sweet. Is that an Eton tie you’re wearing?’

Sweet smiled and fingered his black Air Force tie. ‘Harrods actually.’

‘Jesus,’ said Digby in mock amazement. ‘I didn’t know you’d studied at Harrods, sport. What did you take, modern lingerie?’

Sweet saw Digby’s attitude as a challenge to his charm. He gave him a very warm smile, he was confident that he could make the man like him. Everyone knew that Digby’s record as bomb aimer was second to none.

Young Sergeant Cohen played the anxious host, constantly going to the sideboard for more coffee and pressing all his guests to second helpings of pancakes and honey.

Sergeant Battersby was the last down to breakfast. He was a tall boy of eighteen with frizzy yellow hair, thin arms and legs and a very pale complexion. His eyes scanned the room apologetically and his soft full mouth quivered as he decided not to say how sorry he was to be late. He had less reason than anyone to be delayed. His chin seldom needed shaving and most mornings he merely surveyed it to be sure that the pimples of adolescence had finally gone. They had. His frizzy hair paid little heed to combing and his boots and buttons were always done the night before.

Batters was the only member of Lambert’s crew who was younger and less experienced than Cohen. And Batters was the only member of Lambert’s crew who would have contemplated flying under another captain. Not that he believed that there was any other captain anywhere in the RAF who could compare with Lambert, but Battersby was his flight engineer. An engineer was a pilot’s technical adviser and assistant. He helped operate the controls on take-offs and landings; he had to keep a constant watch on the fuel, oil, and coolant systems, especially the fuel changeovers. As well as this he was expected to know every nut and bolt of the aeroplane and be prepared ‘to carry out practicable emergency repairs during flight’ of anything from a hydraulic gun turret to a camera and from the bombsight to the oxygen system. It was a terrifying responsibility for a shy eighteen-year-old.

Until recently Lambert had flown fifteen bombing raids with an engineer named Micky Murphy, who now flew as part of Flight Lieutenant Sweet’s crew. Some people said that Sweet should never have taken the ox-like Irishman away from Lambert after so many trips together. One of the ground-crew sergeants said it was unlucky, some of Sweet’s fellow officers said it was bad manners, and Digby said it was part of Sweet’s plan to arse-crawl his way to become Marshal of the Royal Air Force.

Each day Batters hung round the ground crew of his aeroplane watching and asking endless questions in his thin high voice. While this added to his knowledge, it did nothing for his popularity. He watched Lambert all the time and hoped for nothing more than the curt word of praise that came after each flight. Batters was an untypical flight engineer. Most of them were more like Micky Murphy, practical men with calloused hands and an instinct for mechanical malfunction. They came from factories and garages, they were apprentices or lathe operators or young clerks with their own motorcycle that they could reassemble blindfold. Battersby would never have their instinct. He’d been a secondary-school boy with one afternoon a week in the metalwork class. Of course Batters could run rings round most of the Squadron’s engineers at written exams and luckily the RAF set high store by paperwork. His father taught physics and chemistry at a school in Lancashire.

I marked your last physics paper while on fire-watching. The headmaster was on duty with me. He’d given the sixth form the same sample paper but he told me that yours was undoubtedly the best. This, I need hardly say, made your father rather proud of you. I am confident however that this will not tempt you to slacken your efforts. Always remember that after the war you will be competing for your place at university with fellows who have been wise enough to contribute to the war in a manner that furthers their academic qualifications.

This week’s sample entrance paper should prove a simple matter. Perhaps I should warn you that the second part of question four does not refer solely to sodium. It requires an answer in depth and its apparent simplicity is intended solely to trap the unwary.

Mrs Cohen came into the breakfast room from the kitchen just as Battersby was helping himself to one pancake and a drip of honey. She was a thin white-haired woman who smiled easily. She pushed half a dozen more upon his plate. Battersby had that sort of effect upon mothers. She asked in quiet careful English if anyone else would like more pancakes. In her hand there was a tall pile of fresh ones.

‘They’re delicious, Mrs Cohen,’ said Ruth Lambert. ‘Did you make them?’

‘It’s a Viennese recipe, Ruth. I shall write it for you.’ They all looked towards Mrs Cohen and she cast her eyes down nervously. They reminded her of the clear-eyed young storm-troopers she had seen smashing the shopfronts in Munich. She had always thought of the British as a pale, pimply, stunted race, with bad teeth and ugly faces, but these airmen too were British. Her Simon was indistinguishable from them. They laughed nervously at the same jokes no matter how often repeated. They spoke too quickly for her, and had their own vocabulary. Emmy Cohen was a little afraid of these handsome boys who set fire to the towns she’d known when a girl. She wondered what went on in their cold hearts, and wondered if her son belonged to them now, more than he did to her.

Mrs Cohen looked at Lambert’s wife. Her WAAF corporal’s uniform was too severe to suit her but she looked trim and businesslike. At Warley Fen she was in charge of the inflatable rafts that bombers carried in case they were forced down into the sea. Nineteen, twenty at the most. Her wrists and ankles still with a trace of schoolgirl plumpness. She was clever, thought Mrs Cohen, for without saying much she was a part of their banter and games. They all envied Lambert his beautiful, childlike wife, and yet to conceal their envy they teased her and criticized her and corrected the few mistakes she made about their planes and their squadron and their war. Mrs Cohen coveted her skill. Lambert seldom joined in the chatter and yet his wife would constantly glance towards him, as though seeking approval or praise. Cheerful little Digby and pale-faced Battersby sometimes gave Lambert the same sort of quizzical look. So, noticed Mrs Cohen, did her son Simon.

It was eight-fifteen when a tall girl in WAAF officer’s uniform stepped through the terrace doors like a character in a drawing-room play. She must have known that the sunlight behind her made a halo round her blonde hair, for she stood there for a few moments looking round at the blue-uniformed men.

‘Good God,’ she said in mock amazement. ‘Someone has opened a tin of airmen.’

‘Hello, Nora,’ said young Cohen. She was the daughter of their next-door neighbour if that’s what you call people who own a mansion almost a mile along the lane.

‘I can only stay a millisecond but I must thank you for sending that divine basket of fruit.’ The elder Cohens had sent the fruit but Nora Ashton’s eyes were on their son. She hadn’t seen him since he’d gained his shiny new navigator’s wing.

‘It’s good to see you, Nora,’ he said.

‘Nora visits her mother almost every weekend,’ said Mrs Cohen.

‘Once a month,’ said Nora. ‘I’m at High Wycombe now, Bomber Command HQ.’

‘You must fiddle the petrol for that old banger of yours.’

‘Of course I do, my pet.’

He smiled. He was no longer a shy thin student but a strong handsome man. She touched the stripes on his arm. ‘Sergeant Cohen, navigator,’ she said and exchanged a glance with Ruth. It was all right: this WAAF corporal clearly had her own man.

Nora pecked a kiss and Simon Cohen briefly took her hand. Then she was gone almost as quickly as she arrived. Mrs Cohen saw her to the door and looked closely at her face when she waved goodbye. ‘Simon is looking fine, Mrs Cohen.’

‘I suppose you are surrounded with sergeants like him at your headquarters place.’

‘No, I’m not,’ said Nora. They seldom saw a sergeant at Bomber Command HQ, they only wiped them off the black-board by the hundred after each attack.

After they had finished eating Cohen passed cigars around. Digby, Sweet, and Lambert took one but Batters said his father believed that smoking caused serious harm to the health. Sweet produced a fine ivory-handled penknife and insisted upon using its special attachment to cut the cigars.

Ruth Lambert got up from the table first. She wanted to make sure their bedroom was left neat and tidy, no hairpins on the floor or face powder spilled on the dressing-table.