Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Skin Deep»

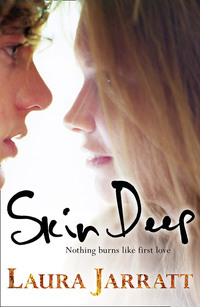

First published in paperback in Great Britain 2012

by Electric Monkey, an imprint of Egmont UK Limited

239 Kensington High Street, London W8 6SA

Text copyright © 2012 Laura Jarratt

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978 1 4052 5672 8

eISBN 978 1 7803 1079 4

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher.

For Mum, who taught me to read and so gave me the key to a bottomless casket of treasure.

Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication page

Rewind

Eight months later . . .

1 – Jenna

2 – Ryan

3 – Jenna

4 – Ryan

5 – Jenna

6 – Ryan

7 – Jenna

8 – Ryan

9 – Jenna

10 – Ryan

11 – Jenna

12 – Ryan

13 – Jenna

14 – Ryan

15 – Jenna

16 – Ryan

17 – Jenna

18 – Ryan

19 – Jenna

20 – Ryan

21 – Jenna

22 – Ryan

23 – Jenna

24 – Ryan

25 – Jenna

26 – Ryan

27 – Jenna

28 – Ryan

29 – Jenna

30 – Ryan

31 – Jenna

32 – Ryan

33 – Jenna

34 – Ryan

35 – Jenna

36 – Ryan

37 – Jenna

38 – Ryan

39 – Jenna

40 – Ryan

41 – Jenna

42 – Ryan

43 – Jenna

44 – Ryan

45 – Jenna

46 – Ryan

47 – Jenna

48 – Ryan

49 – Jenna

50 – Ryan

51 – Jenna

52 – Ryan

53 – Jenna

54 – Ryan

55 – Jenna

56 – Ryan

57 – Jenna

Fast-forward

Acknowledgments

Rewind

The stereo thumps out a drumbeat. Lindsay yells and reaches into the front of the car to turn the volume up – it’s her favourite song. The boys in the front laugh and Rob puts his feet up on the dash. I smile like I’m having a good time, squashed in the middle of the back seat with Lindsay dance-jigging around on my knee and Charlotte and Sarah on either side of me. I wish Steven would slow down because the pitch of the car round the country lanes makes my stomach lurch and I don’t think he should be driving this fast.

Charlotte’s giggling and rubbing Rob’s head over the back of the seat. She likes him, I can tell. He rolls a joint and takes a drag, then passes it to her. She inhales the smoke right down. I shiver inside. Mum and Dad would go crazy if they knew I was in a car with people taking drugs, and if they saw me in Lindsay’s halter-neck top and short skirt. Charlotte passes me the joint and I shake my head. She shrugs, her face scornful, and Lindsay grabs it and takes a few puffs before passing it on.

The car careers round another corner like we’re on a track ride at the funfair.

I sort of wish I was at home, tucked up on the sofa with Mum and Dad and Charlie watching TV. But when the bottle of cider goes round the car, I drink as much as the others so they don’t laugh at me for being the youngest. For being a stupid little girl. My eyes feel funny and heavy with the mascara Lindsay brushed on them earlier. I don’t know who this girl is. It’s not the me who stacks the dishwasher every night for Mum and helps Charlie paint his Warhammer figures at the kitchen table.

I drink more cider, but that doesn’t give me any answers, just makes me feel a bit more like throwing up.

Lindsay leans forward and kisses Steven on the neck. Open-mouthed. Sucking hard. He’ll have a bruise there tomorrow.

Rob laughs. ‘Get a room!’

And Steven waves to him to take the wheel while he cranes round to catch her mouth.

The car swerves and my stomach clenches.

Sarah’s quiet, probably miffed that Charlotte’s after Rob and there’s no one for her.

Lindz whoops as Steven takes the wheel again and floors the accelerator. The car surges forward and hurtles faster and faster down the road.

We hit a straight stretch and Steven spins the wheel from side to side, hands in the air, steering with his knees. Us girls scream and laugh all at once. I force my giggles out.

Something white swoops low in front of the car. Steven shouts out and the car veers towards the hedge.

An owl!

He grabs the wheel and we shriek with relief. My heart steadies again though I feel sicker than ever.

‘Fairy!’ Rob jeers at him and Steven’s face sets harder in the rear-view mirror. His eyes glitter and he slams down on the accelerator.

We’re moving rally-car fast. The January frost coats the hedges in the headlights’ beam as we flash past.

We wheel round another bend into the dip down to Harton Brook. Another twist in the road, and another.

The needle on the speedo reads 70 mph and the girls and I are really screaming. Steven’s knuckles are white on the wheel and even Rob takes his feet down off the glove compartment.

We shoot over the bridge into the bend straight after it.

The stereo bass batters my ears.

And then . . . then the car feels different underneath me. The wheels . . . they glide and spin.

Bumps in the road . . . I can’t feel them any more.

We’re floating.

And I remember. Remember how Mum always nags Dad to slow down here. ‘It’s a frost pocket. There’s black ice here,’ she always says.

Suddenly Rob starts to yell and Sarah shrieks. And I know why the car feels funny. Why it’s skating on the road.

Steven cries out, ‘Shit! Shit!’

The car spins off the road, crashes down the steep bank into the field below.

We’re not gliding any more and my bones shake like they’re falling to pieces.

Thump . . . thump . . . thump from the stereo.

Screaming.

So loud.

I’m thrown upwards as the car turns over.

Then sent slamming down again.

The car rolls once more and my head hits the roof.

Blackness.

Dark.

So dark.

But it’s not safe like it is when I’m snug in my bed. In my own little room.

This is choking dark.

Through it, the screaming reaches me again.

Deafening.

It won’t let me stay, pulls me back to the sound.

I open my eyes.

I’m pressed up against the roof of the car. It’s upside down. Charlotte’s hanging over the back seat, her head half out of the rear window. Blood drips along the shards of the broken glass. Her legs pin me to the roof and I can’t move. My arms are trapped under her. I shove, but she doesn’t move.

There’s a sharp, bitter smell in my nose. I recognise it, but I can’t remember what to call it.

Lindsay’s not on my lap any more. She’s in the front between the seats. Her eyes stare up, wide and glassy. Lifeless.

I wonder why it’s so light, why I can see Lindz, and the panic rises in my throat.

I know.

Coils of light – orange flames – lick towards me.

An acrid stench of burning.

The screaming is coming from me now.

The flames touch me. I can’t move away, can’t get my arms free. They stroke my skin in a white-hot sear of agony.

The pain . . . oh God . . . the pain.

It goes on forever.

A voice yells, sobs, ‘Hang on, I’ll get you out.’ A hand grabs my leg and pulls me hard and fast, away from the flames. Out from under Charlotte’s body.

Rob yanks me out of the door. ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I couldn’t get it open in time.’ One arm hangs useless by his side. He puts the other arm round my waist and half drags, half carries me away.

I know I’m howling with the pain and I can’t stop. Nothing’s ever hurt like this before.

He collapses on to the grass with me. Steven’s bent double beside us, rocking back and forth on his knees. Sarah’s there too, whimpering and holding her head.

Rob looks at me. ‘Oh my God, oh . . .’ and he starts to cry too.

I let myself slide back into the dark again as the car explodes.

Eight months later . . .

1 – Jenna

Ugly people don’t have feelings. They’re not like everyone else. They don’t notice if you stare at them in the street and turn your face away. And if they did notice, it wouldn’t hurt them. They’re not like real people.

Or that’s what I used to think.

When I was younger.

Before I learned.

When I was small, my mother used to take me shopping with her. Thursday is market day in Whitmere and she bought her fruit and vegetables from the organic stall there. The stallholder had a purple-red birthmark running the length of his face and across his mouth. It made his bottom lip stick out, all swollen and wet like a lolling tongue. I wished Mum would buy our food from somewhere else because I had to try to forget his face whenever I looked at the vegetables on my plate or picked up an apple.

He couldn’t speak very well either. I assumed he wasn’t all there in the head. Somehow not looking right made me think his brain was as wrong as his face. I could never stop staring, fascinated by how my stomach turned and how worms crawled along my spine when he sucked back on that flabby lip in a nervous tic. Mum told me off for it when she caught me.

She thought I was being helpful when I washed the fruit and veg for her at home. I never had the courage to tell her I was trying to wash him off them.

Once I asked her if we could buy our stuff from another stall. Why did we always have to go to that one? And she explained what organic meant, about pesticides and fertilisers and protecting wildlife. But she finished with, ‘Besides, some people need our support more than others.’ I never asked again, but I thought it was stupid because ugly people don’t have feelings.

I know better now.

That’s why on a warm day in early September, I wasn’t there for the school photo. I was sitting on the canal bank instead. The Orange River we called it because of the iron deposits in the soil that leached out to stain the water a murky rust colour.

I’d skipped school for the first time ever. Mum would’ve written me a note if I’d asked her, but then I would’ve had to explain and see the understanding come into her eyes. See her blink to hold back tears.

I checked my watch. The girls would be in the toilets now doing their hair and make-up, squealing about how bad they looked. As if. Then they’d line up on the staging in the hall. Best faces for the camera.

Oh, they’d notice I wasn’t there. But nobody would ask why. The teachers would be relieved because when they hung the photo in the school foyer, one face would be missing. I bet they’d even ‘forget’ to ask me for a note.

Ugly people don’t have feelings. We’re not like everyone else.

2 – Ryan

The water in this stretch of the canal was a funny colour – looked like Mum’s carrot soup. I steered the boat along, hand resting on the tiller bar. From the time since we’d last passed a town, I reckoned we must be about ten miles from Whitmere. Time to start looking for a mooring. Didn’t want to get too close. Towns meant trouble. Too many people.

I could hear Mum inside the boat, clattering around and singing some tree-hugger shit to herself as she made dinner. Not tofu again, please. I swear they made that stuff to convert vegans to meat. Cole had agreed with me about that. Tasted like candle wax, he’d said. But then if someone asked Cole what a vegan was, he’d say, ‘It’s someone who farts a lot.’ Death by beans, he used to call Mum’s cooking. It’s not really true. We don’t fart more than everyone else, but when he met us, Cole’s stomach had some trouble readjusting after a life of eating dead cow.

I cruised on a bit further. Nowhere good to stop yet. Too far from any roads. I didn’t fancy hauling my bike over four muddy fields in the middle of winter before I got to the nearest lane.

The smell of bean stew wafted out of the door and I listened to the familiar sound of water lapping on the boat hull as I scanned ahead. There were some houses coming up in about a mile – looked like a village. I squinted for a better view. Only a couple of the houses seemed to be near the canal. The rest were set back. There was bound to be a road nearby so this was a possibility.

I yelled into the boat. ‘Might have found a spot.’

‘I’ll be there in a minute,’ Mum called back.

She always got a buzz when we came to a new place. Me, not so much. Maybe I used to; now it was just same old, same old. This place could be different though. I had a plan for this one. I’d not told Mum yet, but even thinking about it made my stomach churn, in a good way.

It’d be better if Cole was still around to help me break it to her. He’d have backed me up, but he’d been gone a year now. He got tired of travelling, he said – found another woman to hook up with, one with a house and a couple of kids. Mum said I should forget him and move on. Travellers moved on – that’s what we did. But moving on in your head’s harder. I remembered stuff all the time. Things he used to say or do. Times we had a laugh together. Like when I told him about Chavez, the guy Mum was shacked up with before him.

Cole had frowned. ‘Mexican?’

‘Nah, from Bishop’s Stortford. Real name’s Jeremy, but he changed it. Thought he was Che Guevara – if Che spent his life permanently stoned and bumming around on a narrowboat.’

‘Sounds like a tosser to me.’

‘They were all tossers before you.’

He’d winked at me, then raised his voice so Mum could hear. ‘Yeah, well, you gotta kiss a lot of frogs before you meet the handsome prince, eh, Karen?’

Mum, predictably, freaked at him, yelling about women’s emancipation and respect while we cracked up laughing. Then she threw cushions at us until Cole grabbed and tickled her, and made her laugh too.

I spotted a copse of willow trees on the bank ahead, and a bridge across the canal – a road. Were we too near the village? You couldn’t see the houses from here and the footpath was so overgrown that I doubted anyone walked along it often. Cars going over the bridge noticing us? A risk – but the wall was high and if I pulled in just where that alder tree was, I reckoned we’d be tucked away out of sight. This might be it.

Mum came up the steps, shielding her eyes from the sun, and I pointed to the clump of trees.

‘Perfect! My clever son!’

Her hands fluttered round my face, stroking it, touching my hair. She smiled and my stomach churned, in a bad way. That smile was too bright, too fixed. Not right.

‘It’ll be good here. I can sense it. There’s good energy. The ley lines meet here and they’re rising up to greet us.’ She turned that smile on me. ‘It’ll be different here.’

I looked at her, wanting to say, ‘Like you said the last place would be different, and the one before that,’ but I kept my mouth shut. Couldn’t risk unbalancing her mood. Besides, we needed to moor up somewhere and we needed money. Whitmere had a market where she could sell the jewellery she made. Maybe we’d make it through the winter before they moved us on.

I steered Liberty towards the bank. Mum sat on the roof, her bare feet dangling in the doorway. Silver rings on her toes, and in her nose and eyebrow. Hennaed hair glinting copper in the sun. The last of the New Age travellers, who never grew up.

‘Feel that energy, Ryan, feel that energy.’

3 – Jenna

There’s something about waking up early on Saturday morning before the rest of the family. The whole weekend stretched before me and, for a few hours, I had it all to myself. A quiet house. Peace.

My magazine had an article on how exfoliation made the skin glow and apparently people in French spas spent a fortune battering themselves with water jets, so I turned the shower up high enough for the water to sting my shoulders while I scrubbed all over with a loofah. But when it came to washing my face, I turned the spray down. Low pressure, cool water. I never forgot to do that. Couldn’t.

I gave myself a scalp massage with the new hair conditioner, giving it time to soak in before rinsing it off. The bottle said it’d make my hair full and glossy. When I cleaned my teeth, I timed myself with a watch – two minutes like the dentist said. I had to do the flossing blind though; there was no mirror above the basin. I’d thrown the towel stand at it when I got back from hospital. Dad had taken the pieces away without a word. Nobody replaced it.

I sat down at my dressing table to put on the moisturiser and the sunscreen the dermatologist prescribed. It had to be done a certain way – tap the moisturiser in and then massage it thoroughly over the whole scarred area to keep the tissue soft and stop it contracting. The sunscreen was easier and only had to be smoothed over gently. My skin lived by this routine now.

I rough-dried my hair and gave it a quick smooth with the tongs, then threw on a pair of jeans and a T-shirt.

Raggs took one look at me coming down in my old ‘walkies’ trainers and ran around in circles chasing his tail. I grabbed his lead in case we needed it and stuffed it in my pocket with a couple of apples for the ponies and one for myself. He did his usual thing of hurtling down the garden and back to me again, over and over, as if he was on a bungee cord. I caught him up at the gate that led out into the paddock and down to the canal. The paddock was ours, two acres bounded by high hawthorn hedge to shelter the ponies. We bought the Shetland, Ollie, to keep Scrabble company when Lindsay’s horse was sold. It felt like Lindz had died all over again when Clover went, but my dad said no father would be able to stand seeing his daughter’s horse running in the field while she lay buried in the ground.

I whistled to the horses and Ollie headed over first, led by his greedy little tummy. Their velvet noses snorted at my hands as they chomped the apples. Raggs ran along the hedge line, nose to the ground as he followed rabbit trails.

I could see Lindsay’s home clearly through the trees, a Georgian manor house that dwarfed our old farmhouse. There was a figure in the garden, wearing pyjamas and a brown robe. He stood and stared at the rose bushes, statue still. Mr Norman. I hadn’t seen Lindz’s dad for weeks. I watched him for a few minutes, wondering what he was doing, and then he turned and shuffled back into the house, slowly, bent over like an old man.

Best not to think of Lindz today. Not on such a peaceful morning. The pain was always there to catch me if I did, always too raw.

I patted the ponies’ necks and followed Raggs down the field until we got to the thicket of trees that lined the footpath through to the canal. Not many people walked this stretch now it was so overgrown. Raggs disappeared into the undergrowth. He knew this walk as well as I did so I paid no attention and concentrated on picking a path through the nettles. The leaves on the willows above us were still pale green. They’d start to yellow soon, then fall. Raggs and I would kick them up as we walked. He hadn’t seen leaf-fall before – this would be his first autumn. He’d love it.

I lifted a branch aside and came out on to the canal towpath. Raggs was already there peeing up a tree. I patted my leg and he fell in beside me as we strolled along the gravel path. But he stopped abruptly after a few metres, his whole body a line of quivering attention, and I looked up to see what he was watching, expecting to spot a heron or something.

Then I stopped too.

It wasn’t a heron.

A narrowboat was moored up ahead of us and there was a boy on the bank washing the boat windows.

He was stripped to the waist and barefoot, wearing nothing but long shorts. His hair was the colour of the honey Mum bought from the farm shop, his skin tanned the same shade.

I ducked back into the trees, bending to grab Raggs’s collar. We were going to go the other way now, but the stupid dog jerked away from me. I patted my leg frantically, but he ignored me. He took a few steps towards the boy.

‘Come back,’ I whispered. ‘Come back.’

He fidgeted, dancing with his front paws on the spot, and then he made his mind up. He shot off towards the boat, yapping.

‘No! Raggs! Heel! Heel!’

But he’d gone, leaving me cowering in the trees.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.