Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

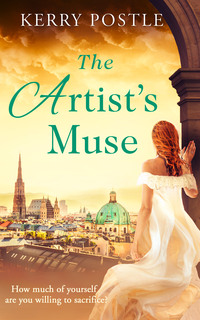

Czytaj książkę: «The Artist’s Muse»

Vienna 1907

Wally Neuzil must find a way to feed her family. Having failed in many vocations, Wally has one last shot: esteemed artist Gustav Klimt needs a muse, and Wally could be the girl he’s been waiting for. But Wally soon discovers that there is much more to her role than just sitting looking pretty. And while she had hoped to establish herself as an emerging lady, the upper classes see her as no more than a prostitute.

With her society dreams dashed Wally finds herself at rock bottom. So when young artist, Egon Schiele, shows her how different life can be Wally grabs hold of the new start she’s been desperately seeking. As a passionate love affair ensues will he be the making of her or her undoing?

The Artist’s Muse

Kerry Postle

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Acknowledgements

Disclaimer

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Endpages

Copyright

KERRY POSTLE

left King’s College London with a distinction in her MA in French Literature. She’s written articles for newspapers and magazines, and has worked as a teacher of Art, French, German, Spanish, and English. She blogs on art and literature.

She lives in Bristol with her husband. They have three grown-up sons.

Kerry is currently working on her second novel set in Franco’s Spain.

Follow her on twitter @kerry_postle

Acknowledgements

For their unwavering support, Simon, Joe, Tom and Harry. For her unfailing belief in me, my mother.

For her time, patience, and curbing of my predilection for ribald double-entendres, Kate.

For their support and expertise, Hannah Smith and Helena Newton at HQ Digital.

I’m indebted to the following works: Jane Kallir’s Life and Works of Egon Schiele for dates and biographical details, Arthur Rimbaud’s poem ‘The Infernal Bridegroom’ from Une Saison en Enfer 1873 for the light it sheds on the nature of Wally and Egon’s relationship, Otto Weininger’s Geschlecht und Charakter 1903 for its insight into the misogyny of the time, and Adelheid Popp’s autobiographical Die Jugendgeschichte einer Arbeiterin 1909 for exposing the hardships faced by working class women at the turn of the century. As for Karl Kraus’s formula for a woman’s soul, I stumbled across it in Edward Timms’ Karl Kraus, Apocalyptic Satirist:Culture and Catastrophe in Habsburg Vienna.

However, I would never have started this novel if I hadn’t visited the Leopold Museum’s stimulating ‘WALLY NEUZIL. Her Life with Egon Schiele’ in 2015. This exhibition posed more questions than it answered. The Artist’s Muse is my response.

Author’s Note

Although inspired by a true story the facts narrated and the characters represented in this novel are fictitious.

For Simon, Joe, Tom and Harry

‘woman is soulless and possesses neither ego nor individuality, personality nor freedom, character nor will.’

Otto Weininger, Sex and Character

Vienna, 1903

Prologue: Vienna

Modelling. The first time I did it, I didn’t like it. But Hilde told me to look as if I did. Or, failing that, to do as I was bid. I was only a child yet the future of my family – now living in Vienna, due to circumstances that I will reveal to you in due course – would depend on how well I got on in Gustav Klimt’s studio one gloomy Tuesday afternoon in November 1907. And Hilde, already successfully established as one of Klimt’s favourites, knew how much I needed – my family needed – this job.

Monday 4th February 1907

We had arrived in Vienna, city of hope, some nine months before that fateful afternoon in the studio, yet I remember it vividly even now. It was a brutally beautiful February day when we made the journey into the big city. As we set off, we must have made a strange sight. Katya was ten, Frieda eight, and Olga only seven, while I – the oldest and biggest of us – was twelve.

I, and even Katya, looked like giants, our young girls’ bodies bursting out of what we had on, exposing uncovered skin at wrist and ankle to the harsh cold of an Austrian winter’s day, while Frieda and Olga, wearing big-sister cast-offs, swept the floor with their hems. Our shoes, squashed-toe small or hand-me-down loose. But we dared not complain for fear of upsetting our mother whose life had now become a veil of tears, the tangible evidence of which she wore with the pride of the recently bereaved. It was hard to lift it up to see what she’d been like before.

Yet I for one was pleased to be going on this adventure. I had never been on a train before and the second the doors slammed shut, the whistle blew, and the engine started to hiss and puff its way out of the station, I was hypnotized. As I looked through the frost-framed windows, so the train took me on a mesmerizing trip past ice swords hanging from snow-tipped trees, single magpies frozen on walls, field upon field of virgin-white snow increasingly disturbed by man the closer we got to the city – and then there was bustle.

We had arrived in another world. We stumbled out of the carriage, our belongings slapping down on the stone platform like dead dogs behind us, our eyes taken this way and that by the coming, going, dashing, crashing, and hurtling in every direction of the bodies now swarming around us. Overwhelmed and in the way, we shuffled, dodged, and collided our way out of the station, the mist of the new gradually lifting to reveal, to my delight, a world of possibilities.

Velvet bows and fur trims whispered to me of riches. Well-soled, perfect boots tapped out the rhythms of success. Education and employment would be ours in this twinkling land of plenty.

I failed to notice my mother’s face, grief-grey, her brow furrowed by the yoke of responsibility, as she led us out into the cold Vienna air.

Like ducklings, we followed her, single file, climbing onto a busy tram, which drove us round the Ringstrasse. Grand and wide, it encompasses Vienna’s heart, and it shone that day, like a band of gold encrusted with monumental jewels shimmering against a heavy sky. Transfixed, I dropped my head against the window, the plump whiteness of my cheek squashed flat against its glass like a suction cup while my mind conjured up a waltzing world of sparkling interiors and sweeping staircases as dazzling façades danced before my eyes.

And I let myself dream of an opulent world, full of luxury, laughter, and ease, of all the magic I would find within this golden ring, encircling as it did this capital of empire. For a little girl like me, with her imagination full of grand balls and princes (who weren’t going to die in the night), the Ringstrasse was an ideal place to be.

The tram juddered. It veered to the right, crossed over connecting lines. But my cheek, momentarily squelched out of position, soon settled back into place while I now marvelled, dribble trickling down my chin, at the mannequins in ballgowns in the glittering window displays of a shopping street. Back in my innocent dream world once more I wondered which dress I would wear to the ball in the house with the sweeping staircase.

Yet in a second, with the blast of a klaxon and the scream of a horse, the spell was broken. Followed closely by the impact.

Your world, the way you see it, can change in an instant.

With the dull thud of metal and wood on flesh I was violently shaken out of my reverie. Something terrible had happened. Within seconds, hordes of people, shouting out excitedly in unrecognizable languages, appeared out of nowhere. It was as if they had pulled themselves up through the cracks in the cobblestones, their sewer-drenched poverty tainting the golden streets of the city of my dreams. Replacing fur-trimmed coats with filth-edged jackets; taffeta ballgowns with worn, ripped clothes.

What did they want? Why were they shouting? The travellers on the tram stood up to find out, blocking my way, though sounds of ugliness pushed their way through. It was only when the tram pulled away that I saw the encircling crowd: baying hounds around their weak and injured quarry. I heard a voice say, ‘’E’ll not get as far as the knacker’s yard,’ but I had no real grasp of what it was that I saw that day, even though I sensed its menace. I dream about it still.

However, if the accident had disturbed me, it was clear, from her trembling fingers, that it had disturbed my fragile mother more. She placed a shaking hand on my shoulder. It was time to get off.

She stood up; we followed, watching her exhausted frame nearly collapse as she struggled to lift her bag off the tram. I rushed to help her though she pointed me to little Olga who’d been lifted off the tram by a foreign-looking young man with a thick moustache and a wavy mop of dark hair, a book in a foreign language peeping out of his coat pocket. I said thank you and he nodded. I suspect that he wasn’t a true Austrian.

‘I’m so proud of you, Wally; you’re such a good girl.’ My mother sighed heavily when we’d all made it to the pavement. She gently pushed the hair away from my eyes, before kissing me on the head with a barely audible, ‘I can manage now. Please don’t worry.’ But she couldn’t. And I did.

As we stood there, an old, well-dressed man approached us. Cupping his hand over his mouth, he spoke quietly into my mother’s ear, his eyes roaming furtively over Katya, Olga, Frieda, and me. She found the strength to turn down his kind offer of help that afternoon but as I watched her I wondered how long it would be before she buckled.

It was clear that she was – we all were – going to find it hard to survive in this place of extremes. My poor, sweet, weak mother, her light frame resuming her heavy walk, tears rolling silently down her face, leading us to our new lives with all the enthusiasm of the condemned to the gallows. We knocked on the door of number 12 Favoritenstrasse. We waited for Frau Wittger to open the door with the chipped black paintwork. We had arrived in Vienna.

Chapter 1

The wind is cutting and the trees bare. It will not be easy. But I am twelve years old. We are at number 12 Favoritenstrasse. And I take this as a sign. It is time for me to stand tall, grow up, and look after the people I love. Mama knocks on the door. I stand behind her, holding myself as upright as I can after dragging two deadweight bags – mine and Olga’s – all the way from where we got off the tram.

It’s difficult to even stand (and as I glance round at Olga, whose head is against my skirt, Frieda who’s sitting on her own bag, and Katya who’s standing protectively behind the two of them, I see that I am not the only one of us having trouble), yet I grit my teeth knowing that I will be able to remove my boots with gaping holes in their soles very soon. And I will be strong. No one has come to answer the door to us yet. As I lean past Mama I wonder whether I have grown or she has shrunk since we caught the train from Tattendorf. Either way, one of us has changed. I knock on the door with more force.

As I wait for it to be answered, Mama fidgets and turns the scrap of paper over and over in her hand. She reads it again, just to make sure we’re at the right address and when Frieda asks, ‘Is this it?’ Mama looks to the heavens. I just think: twelve and 12. How could it not be?

Then the door collapses inwards. It’s pulled back with a force so fierce I expect to see cracks in the white plaster of the walls that surround it.

An elderly man, once he’s picked himself back up, stands in the doorway, stopping momentarily to draw a flask to his thirsty lips. He’s so close to us that I can’t fail to see that he has an oversized red nose from which veins trace across his cheeks like tributaries on a map; the whites of his eyes are yellow. He looks the worse for wear, no doubt due to the liquid contents of his flask, which he attempts to drain by holding it upside down until he’s drunk every last precious drop within. He is an intriguingly strange and disturbing sight on this cold and wintry day.

‘… but they’ll be here in a minute,’ a woman’s voice pipes up. ‘You’ve got to go.’

A small, elderly woman with messy grey hair – despite its being pinned back in a bun – now stands at the open door, pushing the man with the flask over the threshold. An evil old crone pops into my mind. Will she lure us in? Pop me, Katya, Olga, and Frieda in the oven? Cook us? Eat us? But I push this wicked witch on through before she sets up permanent residence in my imagination. I never did like the stories she was in.

‘Frau Wittger?’ my mother asks, her voice rising with trepidation: worried that she is, worried that she isn’t.

‘Oh, Oh!’ She pushes the old man with the flask out into the street and we part like the Red Sea as she shoos him on his way. He leaves a sour smell and goes without a struggle, more intent on checking the contents of his flask every other second. He’s forgotten he’s just emptied it down his throat. Sway, swig, puzzled expression. Sway, swig, what? There’s none left?

‘Same time next week, Wittgi?’ he shouts behind him, not hanging round for a reply.

‘Oh!’ The old woman puts one hand to her hair then brushes the front of her skirt with the other, just like Mama used to do when we had visitors. Before father died. ‘Frau Wittger,’ the woman says, ‘that’s me.’ And then, with hushed embarrassment, she leans closer to Mama and whispers, ‘You won’t be seeing him again.’

At this I notice my mother sway a little. I put out my arm to steady her. I fear she’s growing weaker and I have visions of my sisters floating away untethered for want of a mother to hold them in place. Twelve and 12. It’s my time. I can do this. I push them in front of me, Katya included, as I am the eldest, extending my arms around the shoulders of the two younger ones to give strength to their sapling limbs.

Katya copies me, which I don’t begrudge on a day like this. Together we cross and link limbs in an intricate, delicate way. We will be strong together, my sisters and I.

A broad smile stretches out the wrinkles of Frau Wittger’s face, which softens at the sight of us. ‘Oh, such little ones. Such lovely, lovely little ones. Come in, my dears. Look at you all. Oh, my dear girls. Come in. Come in.’

She nods a welcome to me, then Katya, before bending down and taking Olga and Frieda by the hand. I first think her overly clucky, like a broody hen, but as I see my little sisters relax, catch the relief sweeping across Mama’s face, I am soon grateful for the gentleness this stranger brings, and for the excess of warmth with which she tries to thaw us. ‘Oh, you poor dear mites, you’re frozen,’ she cries, as she beckons us inside.

She leads us to our room at the top of the house. We follow in silence, pulling on heavy bags while I clutch tired hands. ‘If you need anything …’; ‘if you get any trouble …’ She bombards us with kindness and offers of help we’ll never remember.

And as we make our way up creaking stairs, and along dark corridors lined with closed doors, she lights up this new and shadowy world with the exuberance of her voice, wraps us in the warmth of her words so that we feel protected from the harsh shouts and coarse laughter that come from the rooms along the way. Though Mother asks, ‘Are we your only guests?’

‘A key, look here, you’ve got a key,’ she pants when she gets to our room at the top of the house. There is a lock, and with a rattle and twist of the key we are in. A sharp blast of icy air hits us. I look at Mama.

Frau Wittger looks to heaven. ‘Oh, it’ll soon be warm, once you makes yourselves all comfortable up here!’ she wheezes, more in hope than belief, and with that she abandons us, taking her optimism with her.

The room is miserable, with a bare wooden floor, its discoloured curtains drawn, drawn to conceal a broken windowpane I discover when I go to open them. Cold air comes in through the cracked glass, causing the curtains to flap around.

Katya tells Mama what she should do: leave, move, go back, say to Frau Wittger … But I know that’s the wrong thing to do. I know that Mama has no choice. Not one of us has any choice other than to stay here, and we’re lucky Frau Wittger’s such a good, kind soul.

I look at the bed and I’m about to suggest to Mama that she go and have a rest in it when there’s a knock on the door. It’s Frau Wittger, now quite flushed, perspiration around her nose and across her forehead. She’s made her way back up the stairs. It hasn’t been easy for her. And there, tucked under one arm, she has the prettiest white bedcover, embroidered with the daintiest of pink rosebuds. Dangling from the other arm is a basket so heavy she puts it down the minute I open the door.

‘For you and your mam,’ she says, offering the bedcover to me. As soon as I take it, she holds her side, clearly in physical discomfort, before bending down to pick up the basket. Once inside, she closes the door and sets the basket down. She hugs Mama before leading her to the bed and helping her to remove her boots.

‘Lie down and rest, dear,’ she says soothingly, though Mama casts a look of anguish over her daughters in protest. ‘That’s why I’m here,’ she assures her softly. ‘Now cover your dear mam up with that cover, why don’t you, girl,’ she tells me. ‘Then you little ones can bring that basket over and we can see what’s inside.’ By the time Olga lifts the cake out, Mama is asleep.

Chapter 2

The first nine months are tough. To set the tone, Mama does not get out of bed for three weeks, and when she does she looks as though a noose has been placed around her neck. Exhausted, that’s what Frau Wittger tells us is the matter with her, but Mama’s not done a day’s work yet.

The elderly woman we’ve only just met cooks, cleans, and cares for us as if we’re her own.

Her rooms are on the same floor as ours and she opens them up to us with a joy that doesn’t blind us to Mama’s suffering but helps us see there’s something more. That Olga and Frieda play ‘searching’ in her drawers full of broken costume jewellery is a rare and unexpected pleasure for this woman with no children, as it is a welcome escape for the little ones from the groans our mother makes as she grapples with her own demons. She’s not a kind stranger for long.

The rent on the room’s been paid in full for the first three months by my father’s sister, Aunt Klara, and Mama’s grateful to Frau Wittger for, well, just about everything else. Having four daughters is not for the financially challenged, ironic considering that’s what Mama is. Even Frau Wittger, no matter how lovely she thinks we are, will soon be struggling to maintain the support she so wants to give us and which she’s under no obligation to provide.

Mama needs to get a job and so do I. I’m twelve, I live at number 12 Favoritenstrasse and I can do this. When I announce I won’t be going to school no one argues – not even Mama. Especially not Mama, when it turns out that the first job she herself gets is the wrong one. She takes it because it’s in a pretty building – all exotic. She thinks she’s crushing flowers when what she’s really doing is making insecticide. As she’s as delicate as a butterfly she was never going to last there for very long.

As Mama leaves I start, but I may as well have kept going round the revolving door as two weeks later I’m out. I’m underage. Someone reported me. Children must receive eight years of school. It’s the law. Who knew? From the number of children in the factory, not many. Mother’s been sentenced to eighteen hours’ imprisonment. That’s certainly tightened the rope around her neck. We’re all worried about her. I’ve just got to get another job. These are fast-changing times.

I go to school with the others for a month. Then I get another job, this time in a bronze factory where I work with the soldering irons. But they are powered by gas. Which makes me pale. Giddy. Ill. I have to see a doctor who tells my mother who’s weaker than me that I need a nourishing diet and plenty of fresh air (which is all that we have to live on).

Mama has lost one job. I have lost two. We’re wasting time, not earning money. Frau Wittger whispers to Mama about the workhouse, the very mention of which is as effective as a dose of smelling salts on her.

And that’s how Mama’s ended up in the glasspaper factory. It’s an unpleasant dirty job, but she does it without complaint. She gets me a job there as a counter, putting glasspaper sheets into packs ready for the salesman to take around the country.

At home things are better for a month or two. We have money for food, bills, even ribbons.

His name is Herr Bergman, the travelling salesman. He doesn’t come in that often. But when he does the other women and girls go into a flutter. Flapping, flirting. He has his favourites who giggle as he whispers in their ears, their dirty-fingernailed glass-dusty hands pressed against their oh-you-saucy-devil-you mouths.

Herr Bergman, the popular travelling salesman.

He’s so busy tending to his admiring flock that he doesn’t notice me at first. I’m quiet, conscientious, don’t even talk to the other girls, as what they like to discuss in hushed tones punctuated by ribald laughter does not interest me at all. But one day – it is the day when I tie my hair with the new shiny black satin ribbons I bought with some of the money Mother allowed me to spend from my wages – he demands a counter, ‘the one with the red hair and the black ribbons’, for the stock he has come in to collect.

And he watches me while I re-count the pile of glasspaper that I set aside for him earlier in the day.

‘… forty-eight, forty-nine, fifty.’

‘Beautiful hands.’ No sooner has he said these words than jealous eyes pierce me. Eyes of women who know exactly what he means.

I am even more silent than usual as I do my work that afternoon, and after a few sarcastic ‘nice hands’ remarks, by the time I go to find my mother to go home, the tense atmosphere has lifted.

But, as I walk along the corridor towards my mother’s workroom, a man’s hand grabs me and pulls me into the stockroom. It’s Herr Bergman. He knows all about me. Feels so concerned for me. Wants to give me a fatherly kiss, because – sad creature that I am – he feels so sorry that I don’t have a father to look after me. I freeze. Can’t move as he gives me his fatherly kiss. Then he releases me. What should I do? What if I lose my job? Should I tell Mama?

For the next few weeks I keep it to myself. Avoiding Herr Bergman. Until I can’t. He comes in one day, leans over to whisper in my ear the way I’ve seen him do to other girls before. But, unlike them, I do not giggle. I do not put my hand to my mouth in an oh-you-saucy-devil sort of way. And as he pushes himself hard against my shoulder I do not move.

‘I’ll see you later, Beautiful Hands! I’ve got a little something for you that I think you’re going to like.’

For the rest of the day I don’t hear the other girls call me names. All I can think about is Herr Bergman.

It’s late but I can’t delay any longer: it’s time to walk along the corridor. Within seconds he’s pulled me into the stockroom, so eager to shower me with paternal affection and give me my surprise that he doesn’t get round to closing the door.

My mother screams. And screams. Her small hands pull at him. With a back sweep of his hand he knocks her to the ground, stepping over her while sneering, ‘I was doing you a favour, you silly cow.’

See now why my voice is getting angrier, my words more knowing? Because I am angry. Shocked. Doing things I shouldn’t be doing, seeing things I shouldn’t be seeing. Forced to grow up quickly. I’d thought of painting my life better than it is, as I’d wished it to be – Lord knows it doesn’t make me feel good to read over what has happened – but I can’t. No. I’ll not give this story a sugar coating, lay claim to an innocence that experience has already tarnished with its guilt-stained hands

Bitterness. That’s its true taste. And if you have a daughter who’d never think or say what I commit to paper, pray she never has to endure what I have had to endure. Because if she does you’ll soon hear a change in her voice.

We are out of work again.

That night in bed, as I cuddle the sleeping Olga on one side and Frieda on the other, the atmosphere is dead calm. Katya is still awake, pretending to read in the corner because she doesn’t know what to say to me. Nor I to her. And so there we are, silently listening. No rain, nor wind to disguise the hysterical sounds of our mother falling apart in the other room.

‘So what am I to do, Frau Wittger? I have no strength left. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be able to protect them. Stupid, stupid, stupid, stupid girls. And after what I’ve done I might never get decent work again. She’ll end up on the streets. They all will. Oh my lovely stupid girls, what will become of them?’

Katya and I, scorched souls silently screaming in the next room, cry tears that run over the molten lava of our mother’s love.

As I listen to Frau Wittger console my mother while she sobs, I wish I’d been strong enough to let Herr Bergman give me what he thought I’d like. If my mother’s to be believed, somebody’s going to give it to me anyway.

‘There, there, dear. There, there. You need to sleep. Believe me, things won’t look so bad in the morning. Your Wally’s a good girl. None of this is her fault. Nor yours either. I’m not promising anything yet but I think I know how we can get over this. Your Wally’s a good girl, and a pretty one. But I think I’ve got a way to make that work for her. Again not promising anything but fingers crossed this could work out well for all of you. Now off you go to bed.’

Mother sleeps on the floor that night, the noose so tight around her neck the next morning her eyes are bulging.

Shot to bits by grief, pain, misfortune, and the challenge of bringing up girls in a city full of predators, Mama’s on the brink of giving up. And who could blame her for that? Not I. But I won’t. I won’t give up. Not ever. I will be strong and do whatever it is Frau Wittger has in mind.