Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Clockwork Sparrow»

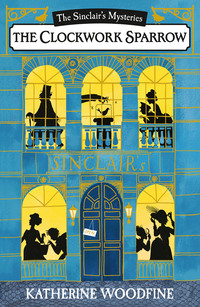

First published in Great Britain 2015

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2015 Katherine Woodfine

Illustrations © 2015 Júlia Sardà

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

First e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978 1 4052 7617 7

Ebook ISBN 978 1 7803 1683 3

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

To Mama and OD,

with much love

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Front series promotional page

PART I: ‘The Straw Sailor’

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

PART II: ‘About Town’

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

PART III: ‘À La Mode’

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

PART IV: ‘Evening elegance’

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

PART V: ‘At Repose’

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Back series promotional page

PART I

‘The Straw Sailor’

This dainty straw hat with a ribbon bow is the essence of charming simplicity. Becoming to every face shape, it is a practical everyday choice for the young working lady . . .

CHAPTER ONE

Sophie hung on tightly to the leather strap as the omnibus rattled forwards. Another Monday morning and, all about her, London was whirring into life: damp and steamy with last night’s rain and this morning’s smoke. As she stood wedged between a couple of clerks wearing bowler hats and carrying newspapers, she gazed out of the window at the grey street, wondering whether that faint fragrance of spring she’d caught on the wind had been just her imagination. She found herself thinking about the garden of Orchard House: the daffodils that must be blooming there now, the damp earth and the smell of rain in the grass.

‘Piccadilly Circus!’ yelled the conductor as the omnibus clattered to a halt, and Sophie pushed her thoughts away. She straightened her hat, grasped her umbrella in a neatly gloved hand, and slipped between the clerks and past an elderly lady wearing a pince-nez, who said ‘Dear me!’ as if quite scandalised at the sight of a young lady alone, recklessly jumping on and off omnibuses. Sophie paid no attention and hopped down on to the pavement. There was simply no sense in listening. After all, she wasn’t that sort of young lady any more.

As the omnibus drew away, she turned and gazed for a moment at the enormous white building that towered above her. Sinclair’s department store was so new that, as yet, it had not even opened its doors to customers. But already it was the most famous store in London – and therefore, some said, the whole world. With its magnificent columns and ranks of coloured flags, it wasn’t like any other shop Sophie had ever seen. It was more like a classical temple that had sprung up, white and immaculate against the smog and dirt of Piccadilly. The huge plate-glass windows were shrouded with royal-blue silk curtains, making it look like the stage in a grand theatre before the performance has begun.

The owner of Sinclair’s department store was Mr Edward Sinclair, who was as famous as the store itself. He was an American, a self-made man, renowned for his elegance, for the single, perfect orchid he always wore in his buttonhole, for the ever-changing string of beautiful ladies on his arm and, most of all, for his wealth. Although they had only been working for him for a few weeks, and most of them had barely set eyes on him, the staff of Sinclair’s had taken to referring to him as ‘the Captain’, because rumour had it that he had run away to sea in his youth. There were already a great number of rumours about Edward Sinclair. But whether the stories were true or not, it seemed an apt nickname. After all, the store itself was a little like a ship: as glittering and luxurious as an ocean liner ready to carry its customers proudly on a journey to an exotic new land.

Somewhere, Sophie could hear a clock chiming. Drawing herself up to her full height – which wasn’t very tall – she lifted her chin and set off smartly round the side of the great building, the little heels of her buttoned boots clicking briskly over the cobbles. As she approached, her heart began to thump, and she put up a hand to check that her hat, with its blue-ribbon bow, was still at exactly the right angle, and that her hair was not coming down. She was part of Sinclair’s department store now: a small cog in this great machine. As such, she knew she must be nothing short of perfect.

Through the doors was another world. The staff corridors were humming with activity. All about her, people were hurrying along carrying palms in pots, or stepladders and tins of paint, or stacks of the distinctive royal-blue and gold Sinclair’s boxes. A smart saleswoman whisked by with an exquisitely beaded evening gown draped carefully over her arm; another hustled along with an armful of parasols, seemingly in a terrific rush; and the strict store manager, Mr Cooper, could be seen dressing down a salesman about the condition of his gloves. Sophie dived in among them and then slipped into the empty cloakroom to take off her coat and hat.

It still seemed extraordinary that she was here at all. Even a year ago, the thought of earning her own living would never have entered her imagination – and now, here she was, a fully fledged shop girl. She paused for a moment before the cloakroom looking-glass to survey her hair, and pushed a hairpin back into place. Mr Cooper was a stickler for immaculate personal appearances, but worse than that, she knew that Edith and the other girls would be only too quick to notice any shortcomings. Once upon a time she had been rather vain about her looks, carefully brushing her hair one hundred times each night and fussing Miss Pennyfeather to tie her velvet ribbon in exactly the right sort of bow, but now she only wanted to look neat and businesslike. She didn’t feel in the least like the girl she had been back then. Her face in the looking glass was familiar, but strange: she looked older somehow, pale and tired and out of sorts.

Her shoulders slumped as she thought of the long week that lay ahead of her, but at once she frowned at herself sharply. Papa would have said that she ought to be thinking about how fortunate she was to be here. There were plenty of others who weren’t so lucky, she reminded herself. She had seen them: girls her own age or even younger, selling apples or little posies of flowers on street corners; girls begging for pennies from passing gentlemen; girls huddled in doorways, wearing clothes that were scarcely more than rags.

Thinking this, she shook her head, squared her shoulders and forced herself to smile. ‘Buck up,’ she told her reflection sternly. Whatever else happened today, she was determined that she wouldn’t give Edith any more excuses to call her stuck-up.

She strode purposefully towards the door, but before she had taken more than a couple of steps, she tripped and fell forwards.

‘Oh!’ exclaimed a voice. As she righted herself, she glanced down to see a boy gazing up at her in alarm. He was sitting on the floor, partly hidden behind a row of coats, and she had fallen over his boots. ‘Are you all right?’

‘What are you doing down there?’ demanded Sophie breathlessly, more embarrassed to have been caught pulling faces and talking to herself than actually hurt. No doubt this boy would make fun of her now, like all the rest, and he’d soon be telling all the others what he had overheard. ‘You shouldn’t hide in corners spying!’ she burst out.

‘I wasn’t spying,’ said the boy, scrambling to his feet. He was wearing the Sinclair’s porters’ uniform – trim dark-blue trousers, a matching jacket with a double row of brass buttons and a peaked hat – but the jacket looked too big for him, the trousers a bit short, and the hat was askew on his untidy, straw-coloured hair. ‘I was reading. ’ For proof, he held out a crumpled story-paper, entitled Boys of Empire, in one grubby hand.

But before Sophie could say anything else, the door slammed open, and a cluster of shop girls pushed their way into the room, in a flurry of skirts and ribbons.

‘Excuse us! Beg your pardon!’

A pretty dark-haired girl caught sight of the boy and smirked. ‘Haven’t you fetched that tin of elbow grease for Jim yet?’ she demanded, sending a ripple of titters through the group.

‘Learned to tie your bootlaces all by yourself, have you?’ another girl giggled.

A third took in Sophie, and made a ridiculous curtsy in her direction. ‘Forgive us, Your Ladyship. We didn’t see that you were gracing us with your presence.’

‘Aren’t you going to introduce us to your young man?’ added the dark-haired girl in an arch tone, making the others laugh even more.

The boy’s cheeks flushed crimson, but Sophie tried her hardest to look indifferent. She had heard this kind of thing many times already during the two weeks of training that all the Sinclair’s shop girls had undertaken. She had realised that she had started all wrong on the very first morning, arriving wearing one of her best dresses – black silk and velvet with jet buttons. She had thought she ought to be smart and make a good first impression, but when she arrived, she realised that every other girl in the room was dressed almost identically, in a plain dark skirt, and a neat white blouse. The rustle and swish of her skirts had made them all look at her, and then begin giggling behind their hands.

‘Who does she think she is? The Lady of the Manor?’ the dark-haired girl, Edith, had whispered.

The next morning she had come carefully dressed in a navy-blue skirt and a white blouse with a little lace collar, but it was already too late. The girls called her ‘Your Ladyship’, or if they wanted to be especially mean, ‘Your Royal Highness’ or ‘Princess Sophie’. All through the training, they made game of the way she spoke, the clothes she wore, the way she did her hair, and especially whenever she was praised by Mr Cooper or Claudine, the store window-dresser.

She had tried hard to look unconcerned, and not to let her feelings show. Papa had always said that in times of war, the most important thing was never to let the enemy see that you were intimidated. Remembering this she saw his face again, almost as if he were standing right in front of her with his bright, dark eyes and neat moustache. He would have been pacing up and down on the hearth rug in his study, the walls hung with maps and treasures he had brought back from distant lands, relating one of his many stories about battles and military campaigns. Keep calm, keep your head, keep a stiff upper lip: those were his mottoes. But the truth was, the more she ignored the other shop girls, the worse they seemed to become. They said she was haughty and high-and-mighty, and called her the name she hated most, ‘Sour-milk Sophie’. Not for the first time, she reflected that perhaps Papa’s advice was not entirely helpful when it came to dealing with horrid shop girls.

Now, she turned away and went out into the passage, the boy trailing behind her. He looked so miserable that she felt a twinge of guilt for having assumed that he would make fun of her, when, in fact, it seemed that they were in the same boat.

‘I shouldn’t pay any attention to them,’ she said.

The boy tried to smile. ‘I really wasn’t spying on you – honest, I wasn’t,’ he said anxiously. ‘I just wanted to finish my serial. I didn’t even notice you were there. It’s the latest Montgomery Baxter.’ Seeing that she looked blank, he went on: ‘It’s about a detective. He’s only a boy, you see, but somehow he always solves the crime and outwits the villain, even when no one else can.’ He beamed at her enthusiastically and, rather to her surprise, Sophie found herself smiling back. ‘I just had to find somewhere out of sight to finish it, so Mr Cooper didn’t catch me reading. Anyway, I’m sorry I tripped you up,’ he finished.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ said Sophie. She held out her hand politely, like Miss Pennyfeather had taught her. ‘I’m Sophie Taylor. I’m in the Millinery Department.’ She had already learned that using her full name, Taylor-Cavendish, would do her no favours here at Sinclair’s. It was safer to stick to plain old Taylor.

‘Billy Parker, apprentice porter,’ he explained, accepting her hand and giving it a firm shake.

‘Parker? Then are you –?’

‘Related to Sidney Parker? Yes. He’s my uncle, worse luck,’ Billy said, grimacing. ‘Oh cripes, and here he comes now,’ he murmured in a lower voice, hastily stuffing the creased story-paper into his pocket as a man came striding towards them along the passageway.

Like everyone else at Sinclair’s, Sophie already knew exactly who Sidney Parker was. He was Head Doorman, in charge of the whole team of doormen and porters, and Mr Cooper’s right-hand man. Tall and handsome in a bullish sort of way, he was impossible to miss in his immaculate uniform. With his hat perfectly brushed, his buttons gleaming and his glossy black moustache always smoothed into place, he couldn’t have been more different from his untidy nephew.

‘Good morning, miss,’ he said, sweeping off his hat with the respectful manner he used for all ladies. Then he turned to Billy. ‘Where do you think you’ve been? Stand up straight, lad – and cheer up, can’t you? You look like a wet weekend.’

He winked at Sophie as though they were sharing a joke at Billy’s expense and then swung the door that led to the shop floor open for her with exaggerated politeness. Throwing a quick smile over her shoulder to Billy, she walked out of the passageway.

CHAPTER TWO

Billy gazed after Sophie as she vanished through the door. She was the first girl in the whole place who hadn’t treated him like he was dirt on the bottom of her shoe. With her golden hair, he decided she looked rather like the heroine of the Montgomery Baxter story he had just been reading. That would, of course, make him the brave boy detective who saves her from deadly peril. He was just beginning to consider exactly what that peril might be when he was brought back to earth by a sharp cuff on the back of the head from Uncle Sid.

‘Don’t pretend to me that you haven’t been larking about again, boy,’ he said curtly. ‘I know everything that goes on in this place, and don’t you forget it. You want to pull your socks up otherwise you’ll be out on your ear. Now shift yourself. Go and help George with the deliveries.’

Billy went down the passage towards the door to the stable-yard, muttering the rudest words he could think of under his breath as soon as Uncle Sid was out of earshot. He couldn’t believe that just two weeks ago, he had actually been looking forward to starting work and doing a man’s job. Now he was here, and all he did was spend each day bored senseless, being treated like everyone’s dogsbody, or getting told off. He’d already had his wages docked twice by Mr Cooper – once for being late and once for having dirty boots. Mum was forever harping on about how lucky he was to have such a fine start, but as far as he was concerned, he’d rather be back at school doing sums. At least he’d been half decent at those.

The stable-yard was warm and damp and smelled of horses and hay. George was sitting alone in a patch of sunlight, squinting at a newspaper, his pipe clamped between his teeth. Blackie, the boiler-room cat, was nearby, thoughtfully washing one paw.

‘Here you are, young feller,’ George said, patting a packing crate beside him. ‘Pull yourself up a pew.’

Suddenly, Billy felt better. It was much nicer here in the stable-yard, away from Uncle Sid and those awful giggling shop girls, and he liked George, who never jeered at him.

‘You’ve got good eyes – read us this bit out,’ said George, pointing with the stem of his pipe.

Billy sat down on the packing case, took the newspaper that George was holding out to him and read aloud:

‘Fancy that,’ said George admiringly. ‘And to think that all that’s going to be coming through here this very morning, jewels that have belonged to queens and the like.’

‘Look at the picture’ said Billy, and they bent over the paper to squint at the blurry photograph.

‘Don’t look much like any sparrow I’ve ever seen,’ said George, contemplating it. ‘A different tune every time, eh? Now however do you reckon they get it to do that?’

At that moment, a cart loaded with boxes of merchandise rumbled into the stable-yard. ‘Shake a leg, George!’ called a voice from behind them. ‘The gaffer wants this lot unloaded sharpish.’

George winked at Billy and then heaved himself to his feet. ‘Come on pal,’ he said. ‘Let’s get on with this and then we’ll finish reading later on.’

Saying that was all very well, but Billy found it was difficult to concentrate on boxes and deliveries. He kept picturing immense diamonds glinting in the dark tunnels of an Indian mine. Then there was Marie Antoinette’s tiara. How had the Captain come to own it? He imagined a grand Paris auction house, or a furtive transaction with a cloaked stranger in a foreign tavern. Busy with these speculations, it seemed no time at all before the boxes were unloaded, and then two shiny black motor vans were pulling into the yard, each driven by a man in white gloves. George nodded to Billy, who stood staring, fascinated by the thought of the priceless treasures that must be within.

But then Uncle Sid strode up. ‘No hanging about, if you please. This isn’t a job for the likes of you. Hop it. Find yourself something useful to do.’

Obediently, Billy walked away, but inwardly he was bristling. At the first sign of something exciting happening, he was told to make himself scarce!

He kicked at the ground, feeling bored and irritable. If only there was something else he could do instead of being a rotten old shop porter. A police detective, solving crimes; the commander of one of those new submarines, keeping the British Empire safe from her enemies; or even an author, writing thrilling tales like those he read in Boys of Empire. Or perhaps he could be a man like the Captain, an adventurer travelling the world, collecting exotic jewels . . . But it was no good even imagining it. Fellows like him just didn’t do that sort of thing.

He wandered gloomily into the stables, thinking that he might be able to find a quiet corner to get on with his story. Bessy, the chestnut mare, put her head over the door of her stall as he approached, and he paused to stroke her. Now, being a cowboy, that would be something, he thought vaguely. Riding on his valiant steed across the great plains of America, like Deadwood Dick or Buffalo Bill –

Suddenly, he stopped short. Something was moving under the hay in the empty stall next to Bessy’s – something much too big to be a rat, or even Blackie the cat.

He gathered his wits quickly. It was probably just some kid mucking about. Sometimes there were children hanging about the store, waifs and strays begging or hoping to earn a penny. Uncle Sid always ordered them away, threatening to set the law on them if they came near the place again. Well if his uncle could do it, he could too. He puffed out his chest and stood taller.

‘Who’s there?’ he demanded. Nothing happened and he began to wonder if he had imagined the rustling movement. He raised his voice and said clearly, much as he imagined the great Montgomery Baxter himself might speak: ‘I know you’re there. Show yourself at once.’

To his astonishment, the hay twitched again – first he saw the glint of a dark suspicious eye, and then a form beginning to emerge. But it wasn’t just a kid, he saw with surprise and then with growing anxiety. It was a youth – a young man really – probably a few years older than he was himself. Bigger than him, anyway. He looked filthy with a lot of dark, curly hair straggling out from underneath an old cap. But what Billy noticed straight away was that his face was badly bruised, and that he held his arm awkwardly. The young man was injured, Billy realised, but all the same he found himself stepping back. It wasn’t that this stranger was threatening exactly, but he wasn’t afraid either: his face showed nothing but a sort of sharp-edged curiosity.

‘Who are you? What do you think you’re doing?’ Billy blustered.

The young man said nothing.

‘You’re trespassing. You’re not allowed to be here. I should get the police.’

The fellow gave him a quick, searching look. Then he spoke. ‘I’m not doing any harm,’ he said in a hoarse voice. ‘I’ll not take nothing. Let me be.’

‘I can’t do that!’ Billy exclaimed. He couldn’t even imagine what Uncle Sid would say if he found that Billy had let some ruffian hang about in the stables. He gathered himself, and said in a voice that was meant to be just as stern as before, except that it would wobble in a most irritating way: ‘You’re to clear off at once, hear me?’

To his annoyance, the stranger suddenly grinned at him. ‘Think you’re a toughie, don’t you, mate?’ he said. ‘Well, all right then, just for you I’ll be off – but I’ll be going in my own time. Why don’t you get back to your work like a good boy?’

Billy felt his fists clenching. Why did everyone always treat him like he was some sort of stupid, useless kid? This fellow was the worst of the lot of them, looking at him with a silly smirk on his dirty face. Well, he would show him. His fear had fled now, and he stepped forwards boldly, striking out with his fists. But all at once, and more deftly than Billy could ever have imagined, the stranger shot out one foot, and Billy found himself face down on the stable floor in a great pile of dirt.

By the time he had picked himself up again, spluttering with indignation, his jacket plastered with horse muck and straw, the strange young man had completely vanished.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.