Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Art of Resistance»

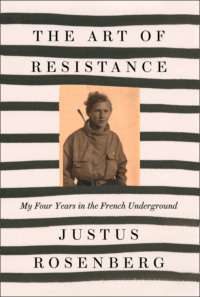

THE ART OF RESISTANCE

My Four Years in the French Underground

A MEMOIR

Justus Rosenberg

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Justus Rosenberg 2020

Cover photograph courtesy of the author

Justus Rosenberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008306052

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780008306038

Version: 2020-02-10

Dedication

I dedicate this book to my wife, Karin Kraft, for her kind forbearance and intelligent feedback at every stage of the writing. She has literally kept me alive through these, my “post-senescent years”—and made it possible for me to write my memoirs.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

MAP OF EUROPE, 1936–1939

MAP OF WESTERN EUROPE, 1940

MAP OF OCCUPIED FRANCE

PROLOGUE

Part I

THE FREE CITY OF DANZIG (1921–1937)

A POGROM GERMAN-STYLE (SPRING 1937)

PREPARING TO LEAVE DANZIG (SUMMER 1937)

AT THE STATION (SEPTEMBER 1937)

BERLIN (SEPTEMBER 2–12, 1937)

Part II

PARIS (SEPTEMBER 1937–SEPTEMBER 3, 1939)

“THE PHONY WAR” (PARIS, SEPTEMBER 1939–JUNE 1940)

THE DEBACLE (PARIS AND BAYONNE, JUNE 1940)

TOULOUSE (JUNE AND JULY 1940)

TO MARSEILLE, IN MARSEILLE (AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 1940)

OVER THE PYRENEES (SEPTEMBER 11–13, 1940)

WALTER BENJAMIN (LATE SEPTEMBER 1940)

VILLA AIR-BEL (NOVEMBER 1940–FEBRUARY 1941)

MAFIA (FEBRUARY–JUNE 1941)

CHAGALL (SPRING 1941)

MAX AND PEGGY DEPART (JULY 1941)

THE EXPULSION OF FRY; MY MOUNTAIN CLIMBING ADVENTURE (AUGUST–DECEMBER 1941)

GRENOBLE (DECEMBER 1941–AUGUST 26, 1942)

Part III

INTERNMENT (AUGUST 27–29, 1942)

ESCAPE (SEPTEMBER 6, 1942)

UNDERGROUND INTELLIGENCE AT MONTMEYRAN (AUTUMN 1942–MARCH 1943)

MANNA FROM THE SKIES (NOVEMBER 1943–MAY 1944)

LAST DAYS ON THE FARM (JUNE 1944)

BECOMING A GUERRILLA (JUNE 1944)

HAUTE CUISINE IN THE CAMP (JUNE–JULY 1944)

THE AMBUSH (JULY 1944)

THE 636TH TANK DESTROYER BATTALION (AUGUST–OCTOBER 1944)

THE TELLER MINE INCIDENT (OCTOBER 11, 1944)

HOMECOMING TO PARIS (DECEMBER 1944–FEBRUARY 15, 1945)

GRANVILLE (FEBRUARY 15–MARCH 8, 1945)

UNRRA (APRIL 1945–OCTOBER 1945)

TO AMERICA (OCTOBER 1945–JULY 13, 1946)

EPILOGUE: WHAT HAPPENED TO …

PICTURE SECTION

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

EUROPE, 1936–1939

WESTERN EUROPE, 1940

OCCUPIED FRANCE

Parfois l’hazard fait bien les choses.

Sometimes chance itself occasions good fortune.

PROLOGUE

THE STREET CLOTHES placed behind the laundry pail in an unobtrusive corner of the hospital lavatory were right where they were supposed to be. I had managed to fake my way out of the Nazi internment camp by feigning agonizing stomach pains, but the last thing I expected was to have an appendectomy actually performed on my gut. The gash in my abdomen was far from healed, but I’d walked to the bathroom at the appointed moment and now, if I could slip into the clothes the Underground operative (disguised as a priest) had left for me, and if I could sashay out of the hospital without raising suspicions, the only thing I had to worry about was riding a bicycle to the halfway house in Lyon, without my intestines spilling onto the boulevard! I made it down the broad hospital stairway and out the heavy lobby doors, and the bicycle was parked by a bench just as planned. Gingerly I mounted the saddle and coasted down the long driveway to the main road, where, standing all the while with one hand on my stomach, I would hopefully pedal my way to freedom. Automobiles whizzed by me, the late summer breeze tousled my hair, but suddenly the whining crescendo of what I thought must be a police siren loomed up behind me. Had I been betrayed? Was I after all about to be sent back to the camp and from there to Auschwitz?

THE FREE CITY OF DANZIG

1921–1937

AS I WRITE this memoir, I am almost one hundred years old—ninety-eight to be exact. The first two years of my life are the hardest to remember. Whenever I try, I hear my parents’ voices, see the contours of their faces, feel the softness of my crib. Everything else I know of my first years I picked up from stories my parents told friends and relatives about their smart son’s first steps and words.

The only objective evidence of my early existence are two photos of an infant sitting on a bear rug, and a birth certificate issued by the Danzig registration office stating that on January 23, 1921, a boy named Justus Rosenberg was born to nineteen-year-old Bluma Solarski, wife of businessman Jacob Rosenberg, age twenty-three, both of the Mosaic faith, as Jewish people were commonly referred to at that time.

Unless you are a stamp collector or interested in the two world wars and the period between them, you’ve probably never heard of Danzig, a seaport on the Baltic, for generations a bone of contention between Germans and Poles. At the Versailles peace conference after World War I, to reward the Poles for having supported the Allies, the League of Nations decided to grant Poland the independence it had lost in 1796, when it was partitioned between Prussia, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Per the Treaty of Versailles, Danzig was to be part of Poland, even though 75 percent of its population was ethnically and culturally German.

Then, to the dissatisfaction of both the Poles and the Germans, on November 15, 1920, the League of Nations declared the disputed territory to be a semiautonomous city-state with its own flag, national anthem, currency, and a constitution patterned after the Weimar Republic. It was to be called “the Free City of Danzig” and to consist of the seaport itself and some two hundred towns and villages in the surrounding area. The League appointed a neutral high commissioner to the infant parliamentary democracy to ensure that the rights of the 20 percent of the population who were Poles and 5 percent who were Jews would be respected. As the name suggested, the Free City had no entrance restrictions. Between 1920 and 1925, in the midst of continuing European political unrest, ninety thousand Jews from Poland and Russia passed through Danzig en route to Canada and the United States. Another six thousand, satisfied with the city-state’s parliamentary democracy and liberal economic policies, or who identified with German culture, chose to remain. My parents, who had no intention of emigrating to America, were among these.

They had come from Mlawa, a Polish shtetl only a few miles from East Prussia, so they spoke German fluently and were familiar with German literature and music. Like most young people of their generation they knew hardly anything of Yiddish culture besides the language itself. My mother, the daughter of a tailor, and my father, born into one of the wealthiest and most learned Jewish families in Mlawa, fell in love when they were very young, and my father had just begun to work in his father’s business. Marriage was out of the question because they belonged to different social classes, so they eloped—to Danzig—and sought to become assimilated into German culture as quickly as possible. Immediately after my birth—which came not long after their elopement—they hired a nanny named Grete, who taught me traditional German children’s ditties, German fairy tales, and the rhymed verses of Struwwelpeter and Max and Moritz. At age six I entered the Volksschule (primary school). I already knew how to read and write both German and Gothic script.

For all practical purposes, I was educated like a typical German child—as was my sister, Lilian, six years my junior. Our parents rarely spoke Yiddish in our presence except when they were discussing something not meant for our ears. Somehow, I picked it up anyway. They celebrated Jewish holidays irregularly and only occasionally attended services at a “reformed” synagogue. Like most Jews in Germany, my parents considered themselves Germans “of the Mosaic persuasion.” They rejected political Zionism, which regarded Judaism as a nation. When I was ten years old, my mother enrolled me at the most prestigious gymnasium in Danzig, the Staatliche Oberrealschule. As was true of many young people in those years, the world of politics fascinated me. At the age of nine, I already dreamed of becoming a diplomat.

In the Danzig elections of 1932, the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Nazis, for short) won the largest number of seats in the Volkskammer (people’s chamber), the legislative assembly. That gave them the right to appoint the “senate” (the executive branch), which until then had consisted of a coalition of liberal democrats, socialists, and moderate conservatives. However, the special nature of the Free City of Danzig, with its role as an international port and financial center, made the Danzig Nazis put a moderate face on their policies and ideology in spite of their victory, and this remained the case for the next five years.

There were, of course, pupils in my class who came to school dressed in Hitler Youth uniforms, but they rarely ostracized me or voiced their displeasure that I, a Jew, was always picked to recite (because of my perfect German diction) the ballads of Schiller or poems by Goethe and other classical poets; nor did they object to my being chosen for the school’s Schlagball team (a German form of baseball). The teachers remained strictly professional. For instance, even after 1932, I was the history teacher’s prize student. I also must have been the favorite of the director of the gymnasium choir, for he recommended me to participate in the all-boy angel-chorus of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, at St. Mary’s Church in town. Thanks to him, I was also selected to sing in the children’s chorus of Bizet’s Carmen at the Danzig City Theater, a theater traditionally subsidized by the municipality that continued to be so under the Nazi government.

I owed my love of singing to my father. As soon as he came home from his office, he would sit down at our old upright piano, play and sing (by ear) popular arias from Italian operas, and invite me to join him, which I enjoyed doing until I developed a taste of my own in music.

One afternoon when I was about fourteen, I heard the “Liebestod” (love-death) aria from Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde on the radio and fell in love with it on first hearing. For reasons I didn’t then understand, Wagner was anathema to my father and certainly not in his repertory. One summer’s day in 1936, when I was fifteen, my parents planned to stay out late, while I planned to take the suburban train to Zoppot and attend whatever was being performed that night at their annual summer, open-air, Wagnerian opera festival. It was Rienzi. Since I had no money for a ticket, I managed to get through a hole in the wire fence that surrounded the place and find an elevated spot with an unimpeded view of the stage. I was also close enough to hear all the subtle harmonies of Wagner’s music. Two years later, I learned that Wagner had been one of the most virulent anti-Semites of the nineteenth century and was Hitler’s favorite composer.

THOUGH MY FATHER’S father had not aided him financially after his elopement with my mother, once I was born, tensions eased between them, and my grandfather’s lucrative international business trading in grain was now supporting his son. My father owned a storage facility in town from which he fulfilled wholesale orders. It was on the ground floor of a three-story apartment in a pleasant Danzig neighborhood. A business office and the storage facility opened onto the street. We lived upstairs. Other Jewish businesses flourished in close proximity. Two doors down, for instance, was Levi’s clothing store. This was very convenient for my father and perhaps gave him a false sense of security.

A POGROM GERMAN-STYLE

Spring 1937

EARLY IN 1937, Nazi demonstrators began targeting Jewish businesses in Danzig. My father refused to take them too seriously. He didn’t believe they represented a change in official policy. They were disturbing, of course, for they reminded him of the spontaneous outbursts against the Jews common since the early Middle Ages. In the familiar pattern, anti-Semitic feelings would manifest for a few months and then die down.

Under the Nazis, however, the character of anti-Semitism was changing. Outbreaks of hatred against the Jews would neither be sporadic nor temporary. One beautiful spring day in 1937, I stopped at the window of a bookstore to look at the colorful covers on display. Suddenly my attention was attracted by shouting so loud and so close that it made the windowpane tremble. I tore myself away and headed in the direction of the noise. It was the sound of a group of Nazis chanting slogans and a crowd of onlookers walking along with them. I turned at the end of the block and saw at least thirty people—young and old—howling “Judas verrecke!” (“Let the Jews be slaughtered!”). I wanted to go and warn my parents, but I was curious to see what the Nazis would do. They were not in uniform, and they weren’t alone: a crowd of bystanders in the middle of the street moved slowly along with them. The Nazis themselves were moving slowly, making funny movements with their heads, to the right, then to the left, to take in everything that was happening around them as they marched. The mob beside them kept growing. Soon I really did want to get away and warn my parents, but I was now in the midst of them. I couldn’t move too quickly or I would appear to be abandoning the scene. I kept thinking, confusedly, wishfully, that perhaps they’d just disperse. I remembered my father’s words: “Bah! They’ll get over it; a few months from now everything will settle down.” But things were not about to settle down. These Nazis were getting wilder and wilder, their cries of “Death to the Jews” more and more virulent.

Now I myself was being pushed forward. When would the police show up and prevent them from doing something violent? But the police were nowhere to be seen.

The crowd was being squeezed closer and closer together. The Nazi agitators had reached Steiner’s grocery store, whose attractive shop front had been repainted the previous winter. The display window and the store’s clean, modern interior struck me as strangely out of place in this ominous tumult. I saw several of the Nazis holding bricks in their hands, others brandishing truncheons or carrying buckets of paint.

It happened like a bolt of lightning: a crash of broken glass, and Steiner’s shop window was smashed into shards. The men weren’t shouting anymore; they seemed to be in rapture over their fine work. The crowd remained silent, too, though the hiatus in the uproar didn’t last very long. Steiner came out of his store, his big blue apron hanging over his big belly. The children in the neighborhood were accustomed to making fun of him, and he’d often come out of the store, just like that, to chase them away. Now he looked stunned, surprised, like someone who had been slapped without his knowing why, as if by mistake. He stepped toward the Nazis, his hands out in front of him—begging for mercy? to protect himself? to show peaceful intentions? to reason with them? Suddenly he brought his hands to his face. Someone had thrown something at him and struck him. He stumbled backward, his hands covered with blood, his body careening. Then, with a quick motion, he turned and ran toward a large door at the back of his store. Everyone was surprised to see him escape so deftly, since they had the impression his big bulk was about to collapse on the pavement. He had left his store wide open, but behind the big oak door he seemed to be safe. I let out a sigh of relief.

There was a moment of indecision among the Nazis, and again I had the wishful thought that they would be satisfied. I was wrong. They started shouting again and some of them tore into the store. Cans of food came rolling into the street—sardines and fruit preserves—and they were pushing over pickle barrels, barrels of herring, and wooden crates of smoked sprats. I saw one Nazi pour a big can of oil onto the sidewalk. Some of them were attacking cupboards and shelves. I could hear, coming from inside, the noises of bottles clanking and various nondescript muffled sounds. The Nazis came out of the store one by one and eyed the crowd, each one sure of his strength. They were happy with themselves.

Then one of them noticed Mr. Klein, the tailor, standing next door in front of his shop, hurriedly attempting to close the shutters. The Nazis turned toward him. They seemed to be blaming him for Steiner’s hasty retreat. Mr. Klein was a small man who always dressed sharply, as was appropriate for a tailor. But he had left his jacket inside, and in his suspenders he looked even more diminutive than usual.

“What’s the rush, Dad?” said one of the Nazis, and the others burst out laughing. Before he could answer, another struck him in the face, first a slap, then blows with his fist, harder and harder, until the little man collapsed half unconscious; another kicked him again and again in the ribs, shouting, “Look! This is the way to treat a dirty Jew!” Someone corrected, “Not at all! He deserves the noose!” Mr. Klein wasn’t moving.

Someone kept shouting that the Jews were a plague—the land had to be rid of this vermin. Some others were demolishing everything in the tailor’s shop. Now the crowd was actively joining the Nazis. I was getting seriously worried about my parents and wanted to tear myself away. My father was probably downstairs in the storage facility. I feared the crowd would soon proceed to our street. On my right, I saw a small gap in the throng; I used my elbows and shoulders to make my way through to it. Too bad if they noticed my defection. I’d chance it. I kept moving in the opposite direction of the crowd, trying to look natural, as if I had something to do, despite the “interesting” goings-on here. Little by little I was getting free.

Within a few minutes, I had broken clear and was heading in the direction of my home, perhaps two hundred yards away. I didn’t look back but could hear behind me the sound of metal shutters rolling shut. The crowd was somewhat behind me now. I stopped to catch my breath and took a seat on a wall from which I could observe what was going on.

They were in front of Goldberg’s, a clothing store. The shop was protected by shutters, but some Nazis had found a big iron bar, actually a small girder, with which they were rushing at the store using it as a battering ram. The metal sheets made a noise on the girder’s impact like thunder. The window posts of the shop broke from the force, but the shutters held. The thugs dropped the girder in the middle of the street and tried in a concerted effort to force up the shutters manually. “Eins, zwei, drei, heben! (heave!) Eins, zwei, drei, hoch!” It still held. They tried again. The bolt gave way—slightly. The shutters lifted enough for a few of them to squeeze in underneath them. The crowd roared a cry of victory.

From inside, a woman’s scream, long and high. They pulled up the shutters a bit more and out rolled Goldberg, the crowd dragging and kicking him onto the sidewalk. He raised himself on all fours—the kicking went on. He scurried along the sidewalk in agony as three booted Nazis went at him relentlessly.

More shouts and groans, from inside now. Two Nazis emerged from under the shutter, dragging Frau Goldberg by the hair and by her arm.

I saw all this from my perch as clear as can be, but it was as if I didn’t understand what I was seeing. In films, there were images of violence a bit like it, but they were just films, unreal. Outside the theater everything would be normal again. The Nazis let Frau Goldberg stand up. Her clothes were torn, her face brutally battered, one black eye and eyelid terribly swollen.

I had always thought of Frau Goldberg as a beautiful woman, so beautiful that when I passed her on the street, I slowed down to look at her; when I approached the store, I tarried in hopes that she would be there and that I would see her long, blond hair and her large, soft blue eyes. What I was looking at now wasn’t possible. And yet it was she. I was filled with rage and fear. I wanted to strike out, to smash my fists against the wall, but all I could do was stay quiet, gnash my teeth, and say nothing.

I came down from my perch. I shouldn’t have stayed there. I shouldn’t have seen what I saw. I began to run. How could this street, this street that I crossed every day and that had always been so peaceful … It wasn’t real; it wasn’t real; it wasn’t possible. But I had seen it with my own eyes. It was the truth. I didn’t need to turn around again to see. I didn’t understand. That was all. These people weren’t human beings; this street, this city, was not my city. I saw Frau Goldberg’s face again, the beautiful one, at first, and then the other … I was ashamed.

I was out of breath by the time I reached my father’s storage facility. I couldn’t speak. He had just finished talking to a prospective buyer. I told him what I had just seen, spurting out everything at once, trembling with anger and fear. My father, placid as he always was, didn’t seem surprised by my story, as if it was all just part of the occurrences of life—but he was disturbed by my agitation.

“Calm down, calm down. Yes, I just heard about it. You shouldn’t be upset, that’s what they want probably. They’ll end up quieting down. Anyway, what do you want us to do? Come now, everything will subside. These people are just louts. They’re not the ones to be afraid of. It’s the Nazi politicians who let others act like that that frighten me. Anyway, we’ll see. It’s just a bad time we have to get through, a crisis.”

Nothing I said upset his placidity. My father thought the wave of violence wouldn’t reach him. I was exaggerating, my imagination was playing tricks on me. “Let’s wait a little,” he said, “let’s give ourselves some time.” But I knew it wasn’t my imagination, and that we didn’t have time.

“Please, Dad, close up shop. I’m sure they’re coming this way. When I left them, they were at the Goldbergs’.”

My father was surprised to see me so upset. He put his arm around my shoulders and spoke to me gently.

“Come, come. Don’t work yourself up into a state.” But he saw that there was something really wrong. I remember his exact words. “You’re pale as death. I’ll close up, I’ll close up, since you’re taking it so tragically.”

He went out to lower our shutters and I sat down on a sack of grain. I watched the metal panels come down one after the other as darkness filled the room. In the coolness of this half-light, I felt protected.

I could hear my father out on the street latching the three big padlocks. This time, I thought, it’s really over. We were safe.

My father reentered the building through the back door, and it was he, now, who seemed agitated. He had heard the sound of boots on the pavement. Either they had made it all the way to our street or it was a second group, like another wave.

“Good Lord! You were right! They’re here, a whole mass of them!”

We could hear shouts, the same ones as before. They must have been attacking the first shop on the corner, the bookstore. My father said we should go upstairs, that we’d be okay there.

“From the window, we’ll be able to see what’s happening.”

My mother was coming down the stairs to meet us.

“You locked up? You did well!” she said, visibly relieved.

“I might not have done anything, but Justus was so insistent …” Then he changed his tone and lowered his voice and said to my mother, “He was there. Justus saw everything. Not nice to see. What bastards.”

As we reached our landing on the third floor, we heard muffled blows from not too far away.

“They’re at the Levis’ now,” my father said. “That’s very close!”

There was only one store between the Levis’ and our facility.

Down below we could hear the blows, redoubled in violence. My father had gone over to the window and opened the shutters carefully. He leaned a little outside, then pulled back in quickly. “They’re here.”

My mother had let herself fall into a chair and had begun quietly crying.

Below, they were working a girder like the one they used at the Goldbergs’, slamming into the shuttered door rhythmically with increasing violence. The window collapsed—we could hear the glass shattering. My father went over to the sink and poured himself a large glass of water and drank it in one gulp. He went to the window again, standing on tiptoe to see without having to lean too far out. Through the open window we could hear everything—the insults, the shouts—except when the battering ram struck the shutters and shook the building, about every five or six seconds.

“The shutters must be holding. Maybe they’ll give up,” my father said in a whisper, turning toward us.

One of the demonstrators must have seen him at the window, because they stopped hammering at the shutters and began insulting my father. He stood to the right of the window where he couldn’t be seen but could keep observing the street. Some of the Nazis had gathered stones and were trying to hit our window with them, but by the time the missiles reached the third floor, they didn’t have enough velocity to do much damage. This seemed to tire them out. I thought that they’d start attacking the hall door downstairs again and expected to hear the blows of the battering ram in the hallway. On the other hand, perhaps they’d refrain from invading the building. We in fact were the only Jewish tenants, but did they know that?

I was right about their either being tired or becoming circumspect about the house not being fully infested with Jews. The battering ram did not begin again. They just shouted, “Jewish garbage! You just wait! We’ll be back, we’ll burn down your hovel! Vermin! Dirty Jew! Come downstairs if you have any balls! Hang all the Jews!”

Little by little, they rejoined their comrades, who were already shaking the shutters of a neighboring store. A few citizens had joined them and most of the crowd, behind, still just as curious, followed without saying a word, as before. My father closed the window and with a weary gesture wiped away the sweat from his face.

“Well, my children, it’s over for today.”

THE DAY AFTER these events, the Danzig government took the position that it opposed such acts of violence, even though, of course, it had not deployed police to do anything about what happened the day before.

As a matter of fact, the Nazi president of the Danzig senate assured the Jewish community that physical assaults against the Jews and the destruction of their businesses were breaches of “party discipline.” Nevertheless, my father was no longer so optimistic that the anti-Semitism was just normal, periodically awakened, eastern European behavior. He and my mother now felt that it was only a matter of time before things would get much worse. They began to consider sending me away from Danzig to continue my studies once I passed my final exams at the gymnasium.

In the days that followed, the political climate indeed became more and more turbulent. Personal relationships between German Jews and other Germans began to be affected. Elisabeth, a close friend of my mother, had a brother who was now in the SS. He admonished her not to associate with us. Elisabeth ignored him, for my mother’s friendship meant more to her than her brother’s party affiliation. In Germany, Jews could no longer occupy public offices, marry, or have intimate relations with Germans. They had been forced to resign professorships, and Jewish doctors were only allowed to treat Jewish patients. Anti-Semitism was becoming more and more blatant. But in Danzig all this had been nothing more than a rumor about what was happening in Germany. Now blatant anti-Semitism was more and more frequently striking home.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.