Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Bombs on Aunt Dainty»

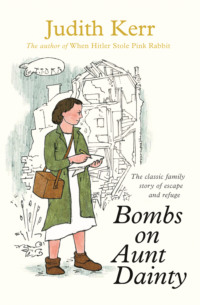

First published in Great Britain as The Other Way Round by

William Collins Sons & Co Ltd in 1975

First published as Bombs on Aunt Dainty by

HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2002

This edition 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd, 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Text copyright © Kerr-Kneale Productions Ltd 1975

Cover illustration and design © Kerr-Kneale Productions Ltd 1975

Judith Kerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007137619

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780007375714

Version: 2017-08-23

For my brother

Michael

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART ONE

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

PART TWO

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Keep Reading

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

Chapter One

Anna was standing in her room at the top of the Bartholomews’ London house. She had finally remembered to stitch up the hem of her skirt which had been hanging down and she was wearing new lisle stockings – not black ones from Woolworth’s but the more expensive beige kind from Marks and Spencer’s. Her sweater, which she had knitted herself, almost matched her skirt, and her pretty shoes, inherited from one of the Bartholomews’ daughters, were newly polished. She tilted the mirror on the dressing table to catch her reflection, hoping to be impressed.

It was disappointing, as usual. The room outdid her. It was clear that she did not belong in it. Against the quilted, silky bedspread, the elegant wallpaper, the beautiful, gleaming furniture, she looked neat but dull. A small person dressed in brown. Like a servant, she thought, or an orphan. The room needed someone careless, richer, more smiling.

She sat on the chintzy stool and stared at her face with growing irritation. Dark hair, green eyes, an over-serious expression. Why couldn’t she at least have been blonde? Everyone knew that blonde hair was better. All the film stars were blonde, from Shirley Temple to Marlene Dietrich. Her eyebrows were wrong, too. They should have been thin arcs, as though drawn with a pencil. Instead they were thick and almost straight. And as for her legs…Anna did not like even to think of her legs, for they were shortish, and to have short legs seemed to her not so much a misfortune as a lapse of taste.

She leaned forward and her reflection came to meet her. At least I look intelligent, she thought. She frowned and pursed her lips, trying to increase the impression. Clever, they had called it at the Metcalfe Boarding School for Girls. That clever little refugee girl. She had not realised at first that it was derogatory. Nobody much had liked her at Miss Metcalfe’s. At least I’ve finished with all that, she thought.

She picked up her handbag – cracked brown leather, an old one of Mama’s brought from Berlin – extracted a powder compact and began carefully to powder her nose. No lipstick, yet. You didn’t wear lipstick at fifteen unless you were fast.

I need never have gone to Miss Metcalfe’s, she thought, if only we’d had a home. It was living in a hotel that had caused all the trouble – that, and having no money. Because when Mama and Papa could no longer pay for her hotel room (even though the hotel was so cheap) she had become like a parcel, to be tossed about, handed from one person to another, without knowing who would be holding her next. The only reason she had gone to Miss Metcalfe’s was that Miss Metcalfe had offered to take her for nothing. The reason she was now living at the Bartholomews’ (though the Bartholomews were, of course, old friends and much nicer than Miss Metcalfe) was that here, too, it did not cost anything.

She sighed. Which hair ribbon, she wondered. For once she had two to choose from – brown or green? She decided on green, slipped it over her head and then back over her hair, and looked at herself. It’s the best I can do, she thought.

A clock somewhere struck ten – time she left. Mama and Papa were expecting her. She picked up her coat and checked her handbag. Keys, torch, identity card, purse. Her purse felt curiously light and she opened it. It was empty. The fourpence for her fare must have fallen out into the bag. She turned the bag upside down. Keys, torch, identity card, powder compact, two pencils, a bus ticket, the paper wrapping off a chocolate biscuit and some crumbs. There was no money. But it must be there, she thought. She’d had it. She was sure she’d had it the previous night. Feverishly, she searched through the pockets of her coat. It wasn’t there either. Oh damn! she thought. Just when I thought I was all right. Oh damn and damn and damn!

She swept the contents back into the bag, took her coat and went out of the room. What am I going to do? she thought, they’ll be waiting for me and I haven’t got my fare.

The landing was dark – the maids must have forgotten to draw back the blackout curtains. Could she borrow from the maids? No, she thought, I can’t. Hoping that, somehow, a miracle would happen, she started down the thickly-carpeted stairs.

In the hall, as she passed what had been the school-room but was now a kind of sitting-room, a friendly American voice called out, “Is that you, Anna? Come in a minute – I haven’t seen you for days.”

Mrs Bartholomew.

Could she ask her?

She opened the door and found Mrs Bartholomew drinking coffee in her dressing gown. She was sitting at the old school-room table and in front of her on the ink-stained surface were a tray and an untidy pile of old children’s books.

“You’re up early on a Sunday,” said Mrs Bartholomew. “Are you off to see your parents?”

Anna thought of answering, “Yes, but I’m afraid I haven’t …” or “Could you possibly lend me …?” Instead, she stood just inside the door and said, “Yes.”

“I bet they’ll be glad to see you.” Mrs Bartholomew waved what appeared to be Hans Andersen. “I’ve been sitting here missing the girls. Judy used to love this book – three, four years ago. Jinny too. It was such fun, wasn’t it, when you all did lessons together!”

Anna reluctantly dragged her mind away from her problem.

“Yes,” she said. It had been fun.

“This war really is crazy,” said Mrs Bartholomew. “Here we all sent our children out of London, thinking that Hitler was going to bomb it out of existence, and a half-year later still nothing at all has happened. Personally, I’m tired of it. I want them back here with me. Jinny says there’s a chance the whole school may move back into town – wouldn’t that be nice?”

“Yes,” said Anna.

“They’d enjoy having you live in the house with them.” Mrs Bartholomew seemed suddenly to notice how Anna was hovering half-in and half-out of the room.

“Well, come in, dear!” she cried. “Have some coffee and tell me – how is everything? How’s the great Polytechnic art course?”

“I really should go,” said Anna, but Mrs Bartholomew insisted, and she found herself sitting at the school-room table with a cup in her hand. Through the window she could see grey clouds and branches waving in the wind. It looked cold. Why couldn’t she have asked for her fare money when she had the chance?

“So what have you been doing? Tell me,” said Mrs Bartholomew.

What had she been doing?

“Well, of course it’s only a junior art course.” It was difficult to bring her mind to bear on it. “We do bits of everything. Last week we all drew each other. I liked doing that.”

The teacher had looked at Anna’s drawing and had told her that she had real talent. She warmed at the memory.

“But of course it’s not very practical – financially, I mean,” she added. The teacher was probably just being nice.

“Now listen!” cried Mrs Bartholomew. “You don’t have to worry about finance at your age. Not while you’re in this house. I know it’s difficult for your parents being in a strange country and everything, but we love having you and you can stay just as long as you like. So you just concentrate on your education. I’m sure you’ll do very, very well, and you must write and tell the girls all about it because they’d love to hear.”

“Yes,” said Anna. “Thank you.”

Mrs Bartholomew looked at her. “Are you all right?” she asked.

“Yes,” said Anna. “Yes, of course. But I think I should go.”

Mrs Bartholomew walked with her into the hall and watched her put on her coat.

“Wait a minute!” she cried, diving into a cupboard, to emerge a moment later with something thick and grey. “You’d better wear Jinny’s scarf.”

She made Anna wind it round her neck and then kissed her on the cheek.

“There!” she said. “Are you sure you’ve got everything you need? Nothing you want?”

Now, surely, was the moment to ask. It would be so simple, and she knew Mrs Bartholomew wouldn’t mind. But standing there in Judy’s shoes and Jinny’s scarf and looking at Mrs Bartholomew’s kind face she found it suddenly impossible. She shook her head and smiled. Mrs Bartholomew smiled back and closed the door.

Damn! thought Anna as she started to trudge up Holland Park Avenue. Now she would have to walk all the way to Bloomsbury because she didn’t have fourpence for the tube.

It was a cold, bright day, and at first she tried to think of it as an adventure.

“I really like exercise,” she said experimentally to Miss Metcalfe in her mind, “as long as it isn’t lacrosse.” But, as usual, she could not extract a satisfactory reply, so she abandoned the conversation.

A few people were still in bed as it was Sunday and you could see their blackout curtains drawn above the shuttered shops. Only the paper shop at Notting Hill Gate was open, with Sunday papers displayed on racks outside and printed posters saying “Latest War News” but, as usual, nothing had happened. The pawnbroker next to the tube station still had the sign which had so much puzzled Anna when she had first come to London and couldn’t speak English properly. It said “Turn Your Old Gold Into Cash”, but a little piece had fallen off the G in Gold, turning it into Cold. Anna remembered how every day, when she had passed it on her way to do lessons with Jinny and Judy, she had wondered what it meant and whether, if she went into the shop and sneezed, they would give her some money.

Of course nowadays no one talking to Anna would guess that she hadn’t spoken English from birth, and she had lost the American accent she had originally picked up from the Bartholomews. She hadn’t been meant just to learn English from them – they had also been meant to learn some of her native German and the French she had acquired in Paris after escaping from Hitler. But it hadn’t worked out like that. She and Jinny and Judy had become friends and spoken English, and Mrs Bartholomew hadn’t minded.

There was a sharp wind blowing across Kensington Gardens. It rattled the signs pointing to air-raid shelters which no one had ever used and the few crocuses still growing between newly-dug trenches looked frozen. Anna pushed her hands deep into the pockets of her old grey coat. Really, she thought, it was ridiculous for her to be walking like this. She was cold, and she would be late, and Mama would wonder where she’d got to. It was ridiculous being so short of money that the loss of fourpence threw everything out of gear. And how could anyone be so stupidly shy as not to be able to borrow fourpence when they needed it? And how had she managed to lose the money, anyway – she was sure she’d had it the previous day, a silver threepenny bit and two halfpennies, she could see them now. I’m sick of it, she thought, I’m sick of being so ineffectual – and Miss Metcalfe’s tall figure rose unbidden before her, cocked a sarcastic eyebrow and said, “Poor Anna!”

Oxford Street was deserted, the windows of the big stores covered in criss-crossings of brown paper to stop them splintering in case of air raids, but Lyons Corner House was open and filled with soldiers queuing for cups of tea. At Oxford Circus the sun came out and Anna felt more cheerful. After all, the reason for her predicament was not only that she was shy. Papa would understand why she couldn’t borrow money from Mrs Bartholomew, not even such a small sum. Her feet were tired, but she was two thirds of the way home and perhaps she was really doing something rather splendid.

“Once,” said a grown-up Anna negligently to an immensely aged Miss Metcalfe. “Once I walked all the way from Holland Park to Bloomsbury rather than borrow fourpence,” and the aged Miss Metcalfe was suitably impressed.

At Tottenham Court Road a newsvendor had spread an array of Sunday papers along the pavement. She read the headlines (“Tea Ration Soon?” “Bring Back The Evacuees!” and “English Dog Lovers Exposed”) before she noticed the date. It was the fourth of March 1940, exactly seven years since she had left Berlin to become a refugee. Somehow this seemed significant. Here she was, penniless but coping triumphantly, on the anniversary of the day her wanderings had begun. Nothing could get her down. Perhaps one day when she was rich and famous everyone would look back …

“Of course I remember Anna,” said the aged Miss Metcalfe to the interviewer from Pathé Newsreel, “She was so bold and resourceful – we all admired her tremendously.”

She trudged up High Holborn. As she turned down Southampton Row, not very far now from the hotel, she noticed a faint clinking in the hem of her coat. Surely it couldn’t be…? Suspiciously, she felt around in her pocket. Yes, there was a hole. With a sinking feeling of anticlimax she inserted two fingers and, by lifting up the hem of her coat with the other hand, managed to extract two halfpennies and a threepenny piece which were lying in a little heap at the bottom of the lining. For a moment she stood quite still, looking at it. Then she thought, “Typical!” so vehemently that she found she had said it out loud, to the astonishment of a passing couple. But what could be more typical than her performance that morning? All that embarrassment with Mrs Bartholomew, all that worrying about whether or not she had done the right thing, all that walking and her aching legs, and in the end it had just been a huge waste of time. No one else behaved like this. She was tired of it. She would have to change. Everything would have to change.

With the money clutched in her hand she strode across to the other side of the road where a woman was selling daffodils outside a tea-shop.

“How much?” she asked.

They were threepence a bunch.

“I’ll have one,” she said.

It was a ridiculous piece of extravagance – and the daffodils weren’t worth it, either, she thought, seeing them droop over her hand – but at least it was something. She would give them to Mama and Papa. She would say, “It’s seven years today since we left Germany and I’ve brought you some flowers.” And perhaps the flowers would bring them luck, perhaps Papa would be asked to write something or someone would send him some money and perhaps everything would become quite different, and it would all be just because she’d saved her fare money and bought some daffodils. And even if nothing happened at all, at least Mama and Papa would be pleased and it would cheer them up.

As she pushed open the swing-doors of the Hotel Continental the old porter who had been drowsing behind his desk greeted her in German.

“Your mother has been in quite a state,” he said, “wondering where you’d got to.”

Anna surveyed the lounge. Scattered among the tables and sitting in shabby leatherette chairs were the usual German, Czech and Polish refugees who had made the hotel their home while hoping for something better – but not Mama.

“I’ll go up to her room,” she said, but before she could start a voice called, “Anna!” and Mama burst in from the direction of the public telephone. Her face was pink with excitement and her blue eyes tense.

“Where have you been?” she cried in German. “I’ve just been talking to Mrs Bartholomew. We thought something had happened! And Max is here – he can only stay a little while and he wanted specially to see you.”

“Max?” said Anna. “I didn’t know he was in London.”

“One of his Cambridge friends gave him a lift.” Mama’s face relaxed as always when she spoke of her remarkable son. “He came here first and then he’s meeting some other friends and then they’re all going back together. English friends, of course,” she added for her own pleasure and for the edification of any Germans, Czechs or Poles who might be listening.

As they hurried upstairs Mama noticed the daffodils in Anna’s hand. “What are those?” she asked.

“I bought them,” said Anna.

“Bought them?” cried Mama, but was interrupted in her astonishment by a middle-aged Pole who emerged from a door marked WC.

“The wanderer has returned,” said the Pole in satisfied tones as he observed Anna. “I told you, Madame, that she had probably just been delayed,” and he disappeared into his room on the other side of the corridor.

Anna blushed. “I’m not as late as all that,” she said, but Mama hurried her on.

Papa’s room was on the top floor and as they went in Anna almost fell over Max who was sitting on the end of the bed just inside the door. He said, “Hi, sister!” in English like someone in a film and gave her a brotherly kiss. Then he added in German, “I was just leaving. I’m glad I didn’t miss you.”

Anna said, “It took me ages to get here,” and squeezed round the table which held Papa’s typewriter to embrace Papa. “Bonjour, Papa,” she said, because Papa loved to speak French. He was looking tired but the expression in the intelligent, ironically smiling eyes was as usual. Papa always looked, thought Anna, as though he would be interested in whatever happened even though nowadays he clearly did not expect it to be anything good.

She held out the daffodils. “I got these,” she said. “It’s seven years today since we left Germany and I thought they might bring us all luck.”

They were drooping more than ever but Papa took them from her and said, “They smell of spring.” He filled his toothglass with water and Anna helped him put the flowers in. They immediately fell over the edge of the glass until their heads rested on the table.

“I’m afraid they’ve already overstrained themselves,” said Papa and everyone laughed. Well, at least they had cheered him up. “Anyway,” said Papa, “the four of us are together. After seven years of emigration perhaps one shouldn’t ask for more luck than that.”

“Oh yes one should!” said Mama.

Max grinned. “Seven years is probably as much as anyone actually needs.” He turned to Papa. “What do you think is going to happen about the war? Do you think anything is going to happen at all?”

“When Hitler is ready,” said Papa. “The problem is whether the British will be ready too.”

It was the usual conversation and, as usual, Anna’s mind edged away from it. She sat on the bed next to Max and rested her feet. She liked being in Papa’s room. No matter where they had lived, in Switzerland, Paris or London, Papa’s room had always looked the same. There had always been a table with the typewriter, now getting rather rickety, his books, the section of the wall where he pinned photographs, postcards, anything that interested him, all close together so that even the loudest wallpaper was defeated by their joint size; the portraits of his parents looking remote in Victorian settings, a Meerschaum pipe which he never smoked but liked the shape of, and one or two home-made contraptions which he fondly believed to be practical. At present he was going through a phase of cardboard boxes and had devised a mousetrap out of an upside-down lid propped up by a pencil with a piece of cheese at the base. As the mouse ate the cheese the lid would drop down over it and Papa would then somehow extract the mouse and give it its freedom in Russell Square. So far he had had little success.

“How is your mouse?” asked Anna.

“Still at liberty,” said Papa. “I saw it last night. It has a very English face.”

Max shifted restlessly on the bed beside her.

“No one is worrying about the war in Cambridge,” he was saying to Mama. “I went to see the Recruiting Board the other day and they told me very firmly not to volunteer but to get my degree first.”

“Because of your scholarship!” cried Mama proudly.

“No, Mama,” said Max. “It’s the same for all my friends. Everyone has been told to leave it for a couple of years. Perhaps by then Papa might be naturalised.” After four years of public school and nearly two terms at Cambridge Max looked, sounded and felt English. It was maddening for him not to be legally English as well.

“If they make an exception for him,” said Mama.

Anna looked at Papa and tried to imagine him as an Englishman. It was very difficult. Just the same she cried, “Well, they should! He’s not just anyone – he’s a famous writer!”

Papa glanced round the shabby room.

“Not very famous in England,” he said.

There was a pause and then Max got up to go. He embraced Mama and Papa and made a face at Anna. “Walk to the tube with me,” he said. “I’ve hardly seen you.”

They went down the many stairs in silence and as usual the residents of the lounge glanced at Max admiringly as he and Anna walked through. He had always been handsome with his fair hair and blue eyes – not like me, thought Anna. It was nice being with him, but she wished she could have sat a little longer before setting out again.

As soon as they emerged from the hotel Max said in English, “Well, how are things?”

“All right,” said Anna. Max was walking fast and her feet were aching. “Papa is depressed because he offered himself to the BBC for broadcasting propaganda to Germany, and they won’t have him.”

“Why on earth not?”

“It seems he’s too famous. The Germans all know that he’s violently anti-Nazi, so they won’t take any notice of anything he says. At least that’s the theory.”

Max shook his head. “I thought he looked old and tired.” He waited for her to catch him up before he asked, “And what about you?”

“Me? I don’t know.” Suddenly Anna didn’t seem to be able to think of anything but her feet. “I suppose I’m all right,” she said vaguely.

Max looked worried. “But you like your art course?” he asked. “You enjoy that?”

The feet receded slightly from Anna’s consciousness.

“Yes,” she said, “but it’s all so hopeless, isn’t it, when no one has any money? I mean, you read about artists leaving their homes to live in a garret, but if your family is living in a garret already…! I thought perhaps I should get a job.”

“You’re not sixteen yet,” said Max and added almost angrily, “I seem to have had all the luck.”

“Don’t be silly,” said Anna. “A major scholarship to Cambridge isn’t luck.”

They had arrived at Russell Square tube station and one of the lifts was about to close its gates, ready to descend.

“Well—” said Anna, but Max hesitated.

“Listen,” he cried, “why don’t you come up to Cambridge for a weekend?” And as Anna was about to demur, “I can manage the money. You could meet some of my friends and I could show you round a bit – it would be fun!” The lift gates creaked and he made a dash for it. “I’ll write you the details,” he cried as he and the lift sank from sight.

Anna walked slowly back to the hotel. Mama and Papa were waiting for her at one of the tables in the lounge and a faded German lady had joined them.

“…the opera in Berlin,” the German lady was saying to Papa. “You were in the third row of the stalls. I remember my husband pointing you out. I was so excited, and you wrote a marvellous piece about it next morning in the paper.”

Papa was smiling politely.

“Lohengrin, I think,” said the German lady. “Unless it was the Magic Flute or perhaps Aîda. Anyway, it was wonderful. Everything was wonderful in those days.”

Then Papa saw Anna. “Excuse me,” he said. He bowed to the German lady and he and Mama and Anna went into the dining-room for lunch.

“Who was that?” asked Anna.

“The wife of a German publisher,” said Papa. “She got out but the Nazis killed her husband.”

Mama said, “God knows what she lives on.”

It was the usual Sunday lunch, served by a Swiss girl who was trying to learn English but was more likely to pick up a bit of Polish in this place, thought Anna. There were prunes for pudding and there was some difficulty afterwards about paying for Anna’s meal. The Swiss waitress said she would put it on the bill, but Mama said no, it was not an extra item since she herself had missed dinner on the previous Tuesday when she wasn’t feeling well. The waitress said she wasn’t sure if it was all right to transfer meals from one person to another. Mama got excited and Papa looked unhappy and said, “Please don’t make a scene.” In the end the manageress had to be consulted and decided that it was all right this time but must not be regarded as a precedent. By this time a lot of the good had gone out of the day.

“Shall we sit down here or shall we go upstairs?” said Mama when they were back in the lounge – but the German lady was looming and Anna didn’t want to talk about the opera in Berlin, so they went upstairs. Papa perched on the chair, and Anna and Mama sat on the bed.

“I mustn’t forget to give you your fare money for next week,” said Mama, opening her handbag.

Anna looked at her.

“Mama,” she said, “I think I ought to get a job.”