Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Accursed»

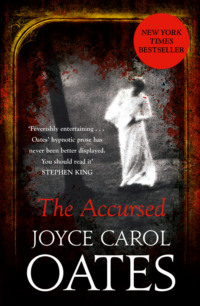

JOYCE CAROL OATES

The Accursed

DEDICATION

for my husband and first reader, Charlie Gross;

and for my dear friends Elaine Pagels and James Cone

EPIGRAPH

From an obscure little village we have become the capital of America.

—ASHBEL GREEN, SPEAKING OF PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, 1783

All diseases of Christians are to be ascribed to demons.

—ST. AUGUSTINE

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Map

Prologue

Part One - DEMON BRIDEGROOM

Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905

Postscript: “Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905”

Narcissus

The Spectral Daughter

Angel Trumpet; Or, “Mr. Mayte of Virginia”

Author’s Note: Princeton Snobbery

The Unspeakable I

The Burning Girl

Author’s Note: The Historian’s Confession

The Spectral Wife

The Demon Bridegroom

Part Two - THE CURSE INCARNATE

The Duel

Postscript: The Historian’s Dilemma

The Unspeakable II

The Cruel Husband

The Search Cont’d

October 1905

“God’s Creation as Viewed from the Evolutionary Hypothesis”

The Phantom Lovers

The Turquoise-Marbled Book

The Bog Kingdom

Postscript: Archaeopteryx

The Curse Incarnate

Part Three - “THE BRAIN, WITHIN ITS GROOVE . . .”

“Voices”

Bluestocking Temptress

The Glass Owl

“Ratiocination Our Salvation”

The Ochre-Runnered Sleigh

“Snake Frenzy”

Postscript: Nature’s Burden

“Defeat at Charleston”

“My Precious Darling . . .”

“A Narrow Fellow in the Grass . . .”

Dr. Schuyler Skaats Wheeler’s Novelty Machine

Quatre Face

“Angel Trumpet” Elucidated

“Armageddon”

Part Four - THE CURSE EXORCISED

Cold Spring

21 May 1906

Lieutenant Bayard by Night

Postscript: On the Matter of the “Unspeakable” at Princeton

“Here Dwells Happiness”

The Nordic Soul

Terra Incognita I

Terra Incognita II

The Wheatsheaf Enigma I

The Wheatsheaf Enigma II

“Sole Living Heir of Nothingness”

The Temptation of Woodrow Wilson

Postscript: “The Second Battle of Princeton”

Dr. De Sweinitz’s Prescription

The Curse Exorcised

A Game of Draughts

The Death of Winslow Slade

“Revolution Is the Hour of Laughter”

The Crosswicks Miracle

Epilogue: The Covenant

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

An event enters “history” when it is recorded. But there may be multiple, and competing, histories; as there are multiple, and competing, eyewitness accounts.

In this chronicle of the mysterious, seemingly linked events occurring in, and in the vicinity of, Princeton, New Jersey, in the approximate years 1900–1910, “histories” have been condensed to a single “history” as a decade in time has been condensed, for purposes of aesthetic unity, to a period of approximately fourteen months in 1905–1906.

I know that a historian should be “objective”—but I am so passionately involved in this chronicle, and so eager to expose to a new century of readers some of the revelations regarding a tragic sequence of events occurring in the early years of the twentieth century in central New Jersey, it is very difficult for me to retain a calm, let alone a scholarly, tone. I have long been dismayed by the shoddy histories that have been written about this era in Princeton—for instance, Q. T. Hollinger’s The Unsolved Enigma of the Crosswicks Curse: A Fresh Inquiry (1949), a compendium of truths, half-truths, and outright falsehoods published by a local amateur historian in an effort to correct the most obvious errors of previous historians (Tite, Birdseye, Worthing, and Croft-Crooke) and the one-time best seller The Vampire Murders of Old Princeton (1938) by an “anonymous” author (believed to be a resident of the West End of Princeton), a notorious exploitive effort that dwells upon the superficial “sensational” aspects of the Curse, at the expense of the more subtle and less evident—i.e., the psychological, moral, and spiritual.

I am embarrassed to state here, so bluntly, at the very start of my chronicle, my particular qualifications for taking on this challenging project. So I will mention only that, like several key individuals in this chronicle, I am a graduate of Princeton University (Class of 1927). I have long been a native Princetonian, born in February 1906, and baptized in the First Presbyterian Church of Princeton; I am descended from two of the oldest Princeton families, the Strachans and the van Dycks; my family residence was that austere old French Normandy stone mansion at 87 Hodge Road, now owned by strangers with a name ending in –stein who, it is said, have barbarously “gutted” the interior of the house and “renovated” it in a “more modern” style. (I apologize for this intercalation! It is not so much an emotional as it is an aesthetic and moral outburst I promise will not happen again.) Thus, though a very young child in the aftermath of the “accursed” era, I passed my adolescence in Princeton at a time when the tragic mysteries were often talked-of, in wonderment and dread; and when the forced resignation of Woodrow Wilson from the presidency of Princeton University, in 1910, was still a matter of both regret and malicious mirth in the community.

Through these connections, and others, I have been privy to many materials unavailable to other historians, like the shocking, secret coded journal of the invalid Mrs. Adelaide McLean Burr, and the intimate (and also rather shocking) personal letters of Woodrow Wilson to his beloved wife Ellen, as well as the hallucinatory ravings of the “accursed” grandchildren of Winslow Slade. (Todd Slade was an older classmate of mine at the Princeton Academy, whom I knew only at a distance.) Also, I have had access to many other personal documents—letters, diaries, journals—never available to outsiders. In addition, I have had the privilege of consulting the Manuscripts and Special Collections of Firestone Library at Princeton University. (Though I can’t boast of having waded through the legendary five tons of research materials like Woodrow Wilson’s early biographer Ray Stannard Baker, I am sure that I’ve closely perused at least a full ton.) I hope it doesn’t sound boastful to claim that of all persons living—now—no one is possessed of as much information as I am concerning the private, as well as the public, nature of the Curse.

The reader, most likely a child of this century, is to be cautioned against judging too harshly these persons of a bygone era. It is naïve to imagine that, in their place, we might have better resisted the incursions of the Curse; or might have better withstood the temptation to despair. It is not difficult for us, living seven decades after the Curse, or, as it was sometimes called, the Horror, had run its course, to recognize a pattern as it emerged; but imagine the confusion, alarm, and panic suffered by the innocent, during those fourteen months of ever-increasing and totally mysterious disaster! No more than the first victims of a terrible plague can know what fate is befalling them, its depth and breadth and impersonality, could the majority of the victims of the Curse comprehend their situation—to see that, beneath the numerous evils unleashed upon them in these ironically idyllic settings, a single Evil lay.

For, consider: might mere pawns in a game of chess conceive of the fact that they are playing-pieces, and not in control of their fate; what would give them the power to lift themselves above the playing board, to a height at which the design of the game becomes clear? I’m afraid that this is not very likely, for them as for us: we cannot know if we act or are acted upon; whether we are playing pieces in the game, or are the very game ourselves.

M. W. van Dyck II

Eaglestone Manor

Princeton, New Jersey

24 June 1984

PROLOGUE

It is an afternoon in autumn, near dusk. The western sky is a spider’s web of translucent gold. I am being brought by carriage—two horses—muted thunder of their hooves—along narrow country roads between hilly fields touched with the sun’s slanted rays, to the village of Princeton, New Jersey. The urgent pace of the horses has a dreamlike air, like the rocking motion of the carriage; and whoever is driving the horses his face I cannot see, only his back—stiff, straight, in a tight-fitting dark coat.

Quickening of a heartbeat that must be my own yet seems to emanate from without, like a great vibration of the very earth. There is a sense of exhilaration that seems to spring, not from within me, but from the countryside. How hopeful I am! How excited! With what childlike affection, shading into wonderment, I greet this familiar yet near-forgotten landscape! Cornfields, wheat fields, pastures in which dairy cows graze like motionless figures in a landscape by Corot . . . the calls of red-winged blackbirds and starlings . . . the shallow though swift-flowing Stony Brook Creek and the narrow wood-plank bridge over which the horses’ hooves and the carriage wheels thump . . . a smell of rich, moist earth, harvest . . . I see that I am being propelled along the Great Road, I am nearing home, I am nearing the mysterious origin of my birth. This journey I undertake with such anticipation is not one of geographical space but one of Time—for it is the year 1905 that is my destination.

1905!—the very year of the Curse.

Now, almost too soon, I am approaching the outskirts of Princeton. It is a small country town of only a few thousand inhabitants, its population swollen by university students during the school term. Spires of churches appear in the near distance—for there are numerous churches in Princeton. Modest farmhouses have given way to more substantial homes. As the Great Road advances, very substantial homes.

How strange, I am thinking—there are no human figures. No other carriages, or motorcars. A stable, a lengthy expanse of a wrought iron fence along Elm Road, behind which Crosswicks Manse is hidden by tall splendid elms, oaks, and evergreens; here is a pasture bordering the redbrick Princeton Theological Seminary where more trees grow, quite gigantic trees they seem, whose gnarled roots are exposed. Now, on Nassau Street, I am passing the wrought iron gate that leads into the university—to fabled Nassau Hall, where once the Continental Congress met, in 1783. Yet, there are no figures on the Princeton campus—all is empty, deserted. Badly I would like to be taken along Bayard Lane to Hodge Road—to my family home; how my heart yearns, to turn up the drive, and to be brought to the very door at the side of the house, through which I might enter with a wild elated shout—I am here! I am home! But the driver does not seem to hear me. Or perhaps I am too shy to call to him, to countermand the directions he has been given. We are passing a church with a glaring white facade, and a high gleaming cross that flashes light in the sun; the carriage swerves, as if one of the horses had caught a pebble in his hoof; I am staring at the churchyard, for now we are on Witherspoon Street, very nearly in the Negro quarter, and the thought comes to me sharp as a knife-blade entering my flesh, Why, they are all dead, now—that is why no one is here. Except me.

PART I

Demon Bridegroom

Ash Wednesday Eve, 1905

1.

Fellow historians will be shocked, dismayed, and perhaps incredulous—I am daring to suggest that the Curse did not first manifest itself on June 4, 1905, which was the disastrous morning of Annabel Slade’s wedding, and generally acknowledged to be the initial public manifestation of the Curse, but rather earlier, in the late winter of the year, on the eve of Ash Wednesday in early March.

This was the evening of Woodrow Wilson’s (clandestine) visit to his longtime mentor Winslow Slade, but also the evening of the day when Woodrow Wilson experienced a considerable shock to his sense of family, indeed racial identity.

Innocently it began: at Nassau Hall, in the president’s office, with a visit from a young seminarian named Yaeger Washington Ruggles who had also been employed as Latin preceptor at the university, to assist in the instruction of undergraduates. (Intent upon reforming the quality of education at Princeton, with its reputation as a Southern-biased, largely Presbyterian boys’ school set beside which its rival Harvard University was a paradigm of academic excellence, Woodrow Wilson had initiated a new pedagogy in which bright young men were hired to assist older professors in their lecture courses; Yaeger Ruggles was one of these young preceptors, popular in the better homes of Princeton as at the university, as eligible bachelors are likely to be in a university town.) Yaeger Ruggles was a slender, slight, soft-spoken fellow Virginian, a distant cousin of Wilson’s who had introduced himself to the university president after he’d enrolled in his first year at the Princeton Theological Seminary; Wilson had personally hired him to be a preceptor, impressed with his courtesy, bearing, and intelligence. At their first meeting, Yaeger Ruggles had brought with him a letter from an elderly aunt, living in Roanoke, herself a cousin of Wilson’s father’s aunt. This web of intricate connections was very Southern; despite the fact that Woodrow Wilson’s branch of the family was clearly more affluent, and more socially prominent than Yaeger Ruggles’s family, who dwelt largely in the mountainous area west of Roanoke, Woodrow Wilson had made an effort to befriend the young man, inviting him to the larger receptions and soirees at his home, and introducing him to the sons and daughters of his well-to-do Princeton associates and neighbors. Though older than Ruggles by more than twenty years, Woodrow Wilson saw in his young kinsman something of himself, at an earlier age when he’d been a law student in Virginia with an abiding interest in theology. (Woodrow Wilson was the son of a preeminent Presbyterian minister who’d been a chaplain for the Confederate Army; his maternal grandfather was a Presbyterian minister in Rome, Georgia, also a staunch religious and political conservative.) At the time of Yaeger Ruggles’s visit to President Wilson, in his office in Nassau Hall, the two had been acquainted for more than two years. Woodrow Wilson had not seen so much of his young relative as he’d wished, for his Princeton social life had to be spent in cultivating the rich and influential. “A private college requires donors. Tuition alone is inadequate”—so Woodrow Wilson said often, in speeches as in private conversations. He did regret not seeing more of Yaeger, for he had but three daughters and no son; and now, with his wife’s chronic ill health, that had become a sort of malaise of the spirit, as well as her advancing age, it was not likely that Woodrow would ever have a son. Yaeger’s warm dark intelligent eyes invariably moved Woodrow to an indefinable emotion, with the intensity of memory. His hair was very dark, as Woodrow’s had once been, but thick and springy, where Woodrow’s was rather thin, combed flat against his head. And there was something thrilling about the young man’s softly modulated baritone voice also, that seemed to remind Wilson of a beloved voice or voices of his childhood in Virginia and Georgia. It had been a wild impulse of Woodrow’s—(since childhood in his rigid Presbyterian household, Woodrow had been prone to near-irresistible urges and impulses of every kind, to which he’d rarely given in)—to begin singing in Yaeger’s presence, that the younger man might join him; for Woodrow had loved his college glee clubs, and liked to think that he had a passably fair tenor voice, if untrained and, in recent years, unused.

But it would be a Protestant hymn Woodrow would sing with Yaeger, something melancholy, mournful, yearning, and deliciously submissive—Rock of Ages, cleft for me! Let me hide myself in Thee! Let the water and the blood, that thy wounded side did flow . . .

Woodrow had not yet heard Yaeger speak in public, but he’d predicted, in Princeton circles, and to the very dean of the seminary himself, that his young “Virginian cousin” would one day be an excellent minister—at which time, Woodrow wryly thought, Yaeger too would understand the value of cultivating the wealthy at the expense of one’s own predilections.

But this afternoon, Yaeger Washington Ruggles was not so composed as he usually was. He appeared to be short of breath, as if he’d bounded up the stone steps of Nassau Hall; he did not smile so readily and so sympathetically as he usually did. Nor was his hurried handshake so firm, or so warm. Woodrow saw with a pang of displeasure—(for it pained him, to feel even an inward rebuke of anyone whom he liked)—that the seminarian’s shirt collar was open at his throat, as if, in an effort to breathe, he’d unconsciously tugged at it; he had not shaved fastidiously and his skin, ordinarily of a more healthy tone than Woodrow’s own, seemed darkened as by a shadow.

“Woodrow! I must speak with you.”

“But of course, Yaeger—we are speaking.”

Woodrow half-rose from his chair, behind his massive desk; then remained seated, in his rather formal posture. The office of the president was booklined, floor to ceiling; windows opened out onto the cultivated green of Nassau Hall’s large and picturesque front lawn, that swept to Nassau Street and the wrought iron gates of the university; and, to the rear, another grassy knoll, that led to Clio and Whig Halls, stately Greek temples of startling if somewhat incongruous Attic beauty amid the darker, Gothic university architecture. Behind Woodrow on the wall was a bewigged portrait of Aaron Burr, Sr., Princeton University’s first president to take office in Nassau Hall.

“Yaeger, what is it? You seem troubled.”

“You have heard, Woodrow? The terrible thing that happened yesterday in Camden?”

“Why, I think that I—I have not ‘heard’ . . . What is it?”

Woodrow smiled, puzzled. His polished eyeglasses winked.

In fact, Woodrow had been hearing, or half-hearing, of something very ugly through the day, at the Nassau Club where he had had lunch with several trustees and near the front steps of Nassau Hall where he’d overheard several preceptors talking together in lowered voices. (It was a disadvantage of the presidency, as it had not been when Woodrow was a popular professor at the university, that, sighting him, the younger faculty in particular seemed to freeze, and to smile at him with expressions of forced courtesy and affability.) And it seemed to him too, that morning at breakfast, in his home at Prospect, that their Negro servant Clytie had been unusually silent, and had barely responded when Woodrow greeted her with his customary warm bright smile—“Good morning, Clytie! What have you prepared for us today?” (For Clytie, though born in Newark, New Jersey, had Southern forebears and could prepare breakfasts of the sort Woodrow had had as a boy in Augusta, Georgia, and elsewhere in the South; she was wonderfully talented, and often prepared a surprise treat for the Wilson family—butternut corn bread, sausage gravy and biscuits, blueberry pancakes with maple syrup, creamy cheese grits and ham-scrambled eggs of which Woodrow, with his sensitive stomach, could eat only a sampling, but which was very pleasing to him as a way of beginning what would likely be one of his complicated, exhausting, and even hazardous days in Nassau Hall.)

Though Woodrow invited Yaeger Ruggles to sit down, the young seminarian seemed scarcely to hear and remained standing; in fact, nervously pacing about in a way that grated on his elder kinsman’s nerves, as Yaeger spoke in a rambling and incoherent manner of—(the term was so vulgar, Woodrow held himself stiff as if in opposition to the very sound)—an incident that had occurred the previous night in Camden, New Jersey—lynching.

And another ugly term which made Woodrow very uneasy, as parents and his Virginian and Georgian relatives were not unsympathetic to the Protestant organization’s goals if not its specific methods—Ku Klux Klan.

“There were two victims, Woodrow! Ordinarily, there is just one—a helpless man—a helpless black man—but last night, in Camden, in that hellish place, which is a center of ‘white supremacy’—there was a male victim, and a female. A nineteen-year-old boy and his twenty-three-year-old sister, who was pregnant. You won’t find their names in the newspapers—the Trenton paper hasn’t reported the lynching at all, and the Newark paper placed a brief article on an inside page. The Klan led a mob of people—not just men but women, and young children—who were looking for a young black man who’d allegedly insulted a white man on the street—whoever the young black man was, no one was sure—but they came across another young man named Pryde who was returning home from work, attacked him and beat him and dragged him to be hanged, and his sister tried to stop them, tried to attack some of them and was arrested by the sheriff of Camden County and handcuffed, then turned over to the mob. By this time—”

“Yaeger, please! Don’t talk so loudly, my office staff will hear. And please—if you can—stop your nervous pacing.”

Woodrow removed a handkerchief from his pocket, and dabbed at his warm forehead. How faint-headed he was feeling! This ugly story was not something Woodrow had expected to hear, amid a succession of afternoon appointments in the president’s office in Nassau Hall.

And Woodrow was seriously concerned that his office staff, his secretary Matilde and her assistants, might overhear the seminarian’s raised voice and something of his words, which could not fail to appall them.

Yaeger protested, “But, Woodrow—the Klan murdered two innocent people last night, hardly more than fifty miles from Princeton—from this very office! That they are ‘Negroes’ does not make their suffering and their deaths any less horrible. Our students are talking of it—some of them, Southerners, are joking of it—your faculty colleagues are talking of it—every Negro in Princeton knows of it, or something of it—the most hideous part being, after the Klan leaders hanged the young man, and doused his body with gasoline and lighted it, his sister was brought to the same site, to be murdered beside him. And the sheriff of Camden County did nothing to prevent the murders and made no attempt to arrest or even question anyone afterward. There were said to have been more than seven hundred people gathered at the outskirts of Camden, to witness the lynchings. Some were said to have crossed the bridge from Philadelphia—the lynching must have been planned beforehand. The bodies burned for some time—some of the mob was taking pictures. What a nightmare! In our Christian nation, forty years after the Civil War! It makes me ill—sick to death . . . These lynchings are common in the South, and the murderers never brought to justice, and now they have increased in New Jersey, there was a lynching in Zarephath only a year ago—where the ‘white supremacists’ have their own church—the Pillar of Fire—and in the Pine Barrens, and in Cape May . . .”

“These are terrible events, Yaeger, but—why are you telling me about them, at such a time? I am upset too, of course—as a Christian, I cannot countenance murder—or any sort of mob violence—we must have a ‘rule of law’—not passion—but—if law enforcement officers refuse to arrest the guilty, and local sentiment makes a criminal indictment and a trial unlikely—what are we, here in Princeton, to do? There are barbarous places in this country, as in the world—at times, a spirit of infamy—evil . . .”

Woodrow was speaking rapidly. By now he was on his feet, agitated. It was not good for him, his physician had warned him, to become excited, upset, or even emotional—since childhood, Woodrow had been an over-sensitive child, and had suffered ill health well into his teens; he could not bear it, if anyone spoke loudly or emotionally in his presence, his heart beat rapidly and erratically bearing an insufficient amount of blood to his brain, that began to “faint”—and so now Woodrow found himself leaning forward, resting the palms of his hands on his desk blotter, his eyesight blotched and a ringing in his ears; his physician had warned him, too, of high blood pressure, which was shared by many in his father’s family, that might lead to a stroke; even as his inconsiderate young kinsman dared to interrupt him with more of the lurid story, more ugly and unfairly accusatory words—“You, Woodrow, with the authority of your office, can speak out against these atrocities. You might join with other Princeton leaders—Winslow Slade, for instance—you are a good friend of Reverend Slade’s, he would listen to you—and others in Princeton, among your influential friends. The horror of lynching is that no one stops it; among influential Christians like yourself, no one speaks against it.”

Woodrow objected, this was not true: “Many have spoken against—that terrible mob violence—‘lynchings.’ I have spoken against—‘l-lynchings.’ I hope that my example as a Christian has been—is—a model of—Christian belief—‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’—it is the lynchpin of our religion . . .” (Damn!—he had not meant to say lynchpin: a kind of demon had tripped his tongue, as Yaeger stared at him blankly. ) “You should know, Yaeger—of course you know—it has been my effort here, at Princeton, to reform the university—to transform the undergraduate curriculum, for instance—and to instill more democracy wherever I can. The eating clubs, the entrenched ‘aristocracy’—I have been battling them, you must know, since I took office. And this enemy of mine—Dean West! He is a nemesis I must defeat, or render less powerful—before I can take on the responsibility of—of—” Woodrow stammered, not knowing what he meant to say. It was often that his thoughts flew ahead of his words, when he was in an emotional mood; which was why, as he’d been warned, and had warned himself, he must not be carried away by any rush of emotion. “—of confronting the Klan, and their myriad supporters in the state, who are not so many as in the South and yet—and yet—they are many . . .”

“ ‘Supporters’ in the state? Do you mean, ‘law-abiding Christian hypocrites’? The hell with them! You must speak out.”

“I—I must—‘speak’—? But—the issue is not so—simple . . .”

It had been a shock to Woodrow, though not exactly a surprise, that, of the twenty-five trustees of Princeton University, who had hired him out of the ranks of the faculty, and whose bidding he was expected to exercise, to a degree, were not, on the whole, as one soon gathered, unsympathetic to the white supremacist doctrine, though surely appalled, as any civilized person would be, by the Klan’s strategies of terror. Keeping the Negroes in their place was the purpose of the Klan’s vigilante activities, and not violence for its own sake—as the Klan’s supporters argued.

Keeping the purity of the white race from mongrelization—this was a yet more basic tenet, with which very few Caucasians were likely to disagree.

But Woodrow could not hope to reason with Yaeger Ruggles, in the seminarian’s excitable mood.

Nor could Woodrow pursue this conversation at the present time, for he had a pressing appointment within a few minutes, with one of his (sadly few) confidants among the Princeton faculty; more urgently, he was feeling unmistakably nauseated, a warning signal of more extreme nausea to come if he didn’t soon take a teaspoonful of the “calming” medicine prescribed to him by Dr. Hatch, kept in a drawer in the president’s desk.

“Well, Yaeger. It is a terrible, terrible thing—as you have reported to me—a ‘lynching’—alleged . . . We may expect this in south Jersey but not in Camden, so near Philadelphia! But I’m afraid I can’t speak with you much longer, as I have an appointment at . . . Yaeger, what on earth is wrong?”

Woodrow was shocked to see that his young kinsman, who had always regarded Woodrow Wilson with the utmost respect and admiration, was now glaring at him, as a sulky and self-righteous adolescent might glare at a parent.

The carelessly shaven jaws were trembling with disdain, or frank dislike. The nostrils were widened, very dark. And the eyes were not so attractive now but somewhat protuberant, like the eyes of a wild beast about to leap.

Yaeger’s voice was not so gently modulated now but frankly insolent: “What is wrong with—who, Woodrow? Me? Or you?”

Woodrow protested angrily, “Yaeger, that’s enough. You may be a distant relation of mine, through my father’s family, but that—that does not—give you the right to be disrespectful to me, and to speak in a loud voice to upset my staff. This ‘ugly episode’—as you have reported it to me—is a good example of why we must not allow our emotions to govern us. We must have a—a civilization of law—and not—not—anarchy.”