Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Jeffrey Eugenides Three-Book Collection: The Virgin Suicides, Middlesex, The Marriage Plot»

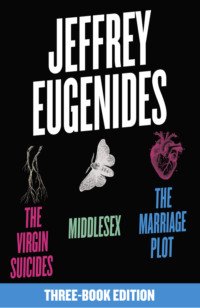

THREE-BOOK EDITION:

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES

MIDDLESEX

THE MARRIAGE PLOT

Jeffrey Eugenides

MAIN CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

The Virgin Suicides

Middlesex

The Marriage Plot

A Note on the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

For Gus and Wanda

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

MAIN CONTENTS

One

On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide—it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese—the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope. They got out of the EMS truck, as usual moving much too slowly in our opinion, and the fat one said under his breath, “This ain’t TV, folks, this is how fast we go.” He was carrying the heavy respirator and cardiac unit past the bushes that had grown monstrous and over the erupting lawn, tame and immaculate thirteen months earlier when the trouble began.

Cecilia, the youngest, only thirteen, had gone first, slitting her wrists like a Stoic while taking a bath, and when they found her, afloat in her pink pool, with the yellow eyes of someone possessed and her small body giving off the odor of a mature woman, the paramedics had been so frightened by her tranquillity that they had stood mesmerized. But then Mrs. Lisbon lunged in, screaming, and the reality of the room reasserted itself: blood on the bath mat; Mr. Lisbon’s razor sunk in the toilet bowl, marbling the water. The paramedics fetched Cecilia out of the warm water because it quickened the bleeding, and put a tourniquet on her arm. Her wet hair hung down her back and already her extremities were blue. She didn’t say a word, but when they parted her hands they found the laminated picture of the Virgin Mary she held against her budding chest.

That was in June, fish-fly season, when each year our town is covered by the flotsam of those ephemeral insects. Rising in clouds from the algae in the polluted lake, they blacken windows, coat cars and streetlamps, plaster the municipal docks and festoon the rigging of sailboats, always in the same brown ubiquity of flying scum. Mrs. Scheer, who lives down the street, told us she saw Cecilia the day before she attempted suicide. She was standing by the curb, in the antique wedding dress with the shorn hem she always wore, looking at a Thunderbird encased in fish flies. “You better get a broom, honey,” Mrs. Scheer advised. But Cecilia fixed her with her spiritualist’s gaze. “They’re dead,” she said. “They only live twenty-four hours. They hatch, they reproduce, and then they croak. They don’t even get to eat.” And with that she stuck her hand into the foamy layer of bugs and cleared her initials: C.L.

We’ve tried to arrange the photographs chronologically, though the passage of so many years has made it difficult. A few are fuzzy but revealing nonetheless. Exhibit #1 shows the Lisbon house shortly before Cecilia’s suicide attempt. It was taken by a real estate agent, Ms. Carmina D’Angelo, whom Mr. Lisbon had hired to sell the house his large family had long outgrown. As the snapshot shows, the slate roof had not yet begun to shed its shingles, the porch was still visible above the bushes, and the windows were not yet held together with strips of masking tape. A comfortable suburban home. The upper-right second-story window contains a blur that Mrs. Lisbon identified as Mary Lisbon. “She used to tease her hair because she thought it was limp,” she said years later, recalling how her daughter had looked for her brief time on earth. In the photograph Mary is caught in the act of blow-drying her hair. Her head appears to be on fire but that is only a trick of the light. It was June 13, eighty-three degrees out, under sunny skies.

•

When the paramedics were satisfied they had reduced the bleeding to a trickle, they put Cecilia on a stretcher and carried her out of the house to the truck in the driveway. She looked like a tiny Cleopatra on an imperial litter. We saw the gangly paramedic with the Wyatt Earp mustache come out first—the one we’d call “Sheriff” when we got to know him better through these domestic tragedies—and then the fat one appeared, carrying the back end of the stretcher and stepping daintily across the lawn, peering at his police-issue shoes as though looking out for dog shit, though later, when we were better acquainted with the machinery, we knew he was checking the blood pressure gauge. Sweating and fumbling, they moved toward the shuddering, blinking truck. The fat one tripped on a lone croquet wicket. In revenge he kicked it; the wicket sprang loose, plucking up a spray of dirt, and fell with a ping on the driveway. Meanwhile, Mrs. Lisbon burst onto the porch, trailing Cecilia’s flannel nightgown, and let out a long wail that stopped time. Under the molting trees and above the blazing, overexposed grass those four figures paused in tableau: the two slaves offering the victim to the altar (lifting the stretcher into the truck), the priestess brandishing the torch (waving the flannel nightgown), and the drugged virgin rising up on her elbows, with an otherworldly smile on her pale lips.

Mrs. Lisbon rode in the back of the EMS truck, but Mr. Lisbon followed in the station wagon, observing the speed limit. Two of the Lisbon daughters were away from home, Therese in Pittsburgh at a science convention, and Bonnie at music camp, trying to learn the flute after giving up the piano (her hands were too small), the violin (her chin hurt), the guitar (her fingertips bled), and the trumpet (her upper lip swelled). Mary and Lux, hearing the siren, had run home from their voice lesson across the street with Mr. Jessup. Barging into that crowded bathroom, they registered the same shock as their parents at the sight of Cecilia with her spattered forearms and pagan nudity. Outside, they hugged on a patch of uncut grass that Butch, the brawny boy who mowed it on Saturdays, had missed. Across the street, a truckful of men from the Parks Department attended to some of our dying elms. The EMS siren shrieked, going away, and the botanist and his crew withdrew their insecticide pumps to watch the truck. When it was gone, they began spraying again. The stately elm tree, also visible in the foreground of Exhibit #1, has since succumbed to the fungus spread by Dutch elm beetles, and has been cut down.

The paramedics took Cecilia to Bon Secours Hospital on Kercheval and Maumee. In the emergency room Cecilia watched the attempt to save her life with an eerie detachment. Her yellow eyes didn’t blink, nor did she flinch when they stuck a needle in her arm. Dr. Armonson stitched up her wrist wounds. Within five minutes of the transfusion he declared her out of danger. Chucking her under her chin, he said, “What are you doing here, honey? You’re not even old enough to know how bad life gets.”

And it was then Cecilia gave orally what was to be her only form of suicide note, and a useless one at that, because she was going to live: “Obviously, Doctor,” she said, “you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl.”

•

The Lisbon girls were thirteen (Cecilia), and fourteen (Lux), and fifteen (Bonnie), and sixteen (Mary), and seventeen (Therese). They were short, round-buttocked in denim, with roundish cheeks that recalled that same dorsal softness. Whenever we got a glimpse, their faces looked indecently revealed, as though we were used to seeing women in veils. No one could understand how Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon had produced such beautiful children. Mr. Lisbon taught high-school math. He was thin, boyish, stunned by his own gray hair. He had a high voice, and when Joe Larson told us how Mr. Lisbon had cried when Lux was later rushed to the hospital during her own suicide scare, we could easily imagine the sound of his girlish weeping.

Whenever we saw Mrs. Lisbon we looked in vain for some sign of the beauty that must have once been hers. But the plump arms, the brutally cut steel-wool hair, and the librarian’s glasses foiled us every time. We saw her only rarely, in the morning, fully dressed though the sun hadn’t come up, stepping out to snatch up the dewy milk cartons, or on Sundays when the family drove in their paneled station wagon to St. Paul’s Catholic Church on the Lake. On those mornings Mrs. Lisbon assumed a queenly iciness. Clutching her good purse, she checked each daughter for signs of makeup before allowing her to get in the car, and it was not unusual for her to send Lux back inside to put on a less revealing top. None of us went to church, so we had a lot of time to watch them, the two parents leached of color, like photographic negatives, and then the five glittering daughters in their homemade dresses, all lace and ruffle, bursting with their fructifying flesh.

Only one boy had ever been allowed in the house. Peter Sissen had helped Mr. Lisbon install a working model of the solar system in his classroom at school, and in return Mr. Lisbon had invited him for dinner. He told us the girls had kicked him continually under the table, from every direction, so that he couldn’t tell who was doing it. They gazed at him with their blue febrile eyes and smiled, showing their crowded teeth, the only feature of the Lisbon girls we could ever find fault with. Bonnie was the only one who didn’t give Peter Sissen a secret look or kick. She only said grace and ate her food silently, lost in the piety of a fifteen-year-old. After the meal Peter Sissen asked to go to the bathroom, and because Therese and Mary were both in the downstairs one, giggling and whispering, he had to use the girls’, upstairs. He came back to us with stories of bedrooms filled with crumpled panties, of stuffed animals hugged to death by the passion of the girls, of a crucifix draped with a brassiere, of gauzy chambers of canopied beds, and of the effluvia of so many young girls becoming women together in the same cramped space. In the bathroom, running the faucet to cloak the sounds of his search, Peter Sissen found Mary Lisbon’s secret cache of cosmetics tied up in a sock under the sink: tubes of red lipstick and the second skin of blush and base, and the depilatory wax that informed us she had a mustache we had never seen. In fact, we didn’t know whose makeup Peter Sissen had found until we saw Mary Lisbon two weeks later on the pier with a crimson mouth that matched the shade of his descriptions.

He inventoried deodorants and perfumes and scouring pads for rubbing away dead skin, and we were surprised to learn that there were no douches anywhere because we had thought girls douched every night like brushing their teeth. But our disappointment was forgotten in the next second when Sissen told us of a discovery that went beyond our wildest imaginings. In the trash can was one Tampax, spotted, still fresh from the insides of one of the Lisbon girls. Sissen said that he wanted to bring it to us, that it wasn’t gross but a beautiful thing, you had to see it, like a modern painting or something, and then he told us he had counted twelve boxes of Tampax in the cupboard. It was only then that Lux knocked on the door, asking if he had died in there, and he sprang to open it. Her hair, held up by a barrette at dinner, fell over her shoulders now. She didn’t move into the bathroom but stared into his eyes. Then, laughing her hyena’s laugh, she pushed past him, saying, “You done hogging the bathroom? I need something.” She walked to the cupboard, then stopped and folded her hands behind her. “It’s private. Do you mind?” she said, and Peter Sissen sped down the stairs, blushing, and after thanking Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon, hurried off to tell us that Lux Lisbon was bleeding between the legs that very instant, while the fish flies made the sky filthy and the streetlamps came on.

•

When Paul Baldino heard Peter Sissen’s story, he swore that he would get inside the Lisbons’ house and see things even more unthinkable than Sissen had. “I’m going to watch those girls taking their showers,” he vowed. Already, at the age of fourteen, Paul Baldino had the gangster gut and hit-man face of his father, Sammy “the Shark” Baldino, and of all the men who entered and exited the big Baldino house with the two lions carved in stone beside the front steps. He moved with the sluggish swagger of urban predators who smelled of cologne and had manicured nails. We were frightened of him, and of his imposing doughy cousins, Rico Manollo and Vince Fusilli, and not only because his house appeared in the paper every so often, or because of the bulletproof black limousines that glided up the circular drive ringed with laurel trees imported from Italy, but because of the dark circles under his eyes and his mammoth hips and his brightly polished black shoes which he wore even playing baseball. He had also snuck into other forbidden places in the past, and though the information he brought back wasn’t always reliable, we were still impressed with the bravery of his reconnaissance. In sixth grade, when the girls went into the auditorium to see a special film, it was Paul Baldino who had infiltrated the room, hiding in the old voting booth, to tell us what it was about. Out on the playground we kicked gravel and waited for him, and when he finally appeared, chewing a toothpick and playing with the gold ring on his finger, we were breathless with anticipation.

“I saw the movie,” he said. “I know what it’s about. Listen to this. When girls get to be about twelve or so”—he leaned toward us—“their tits bleed.”

Despite the fact that we now knew better, Paul Baldino still commanded our fear and respect. His rhino’s hips had gotten even larger and the circles under his eyes had deepened to a cigar-ash-and-mud color that made him look acquainted with death. This was about the time the rumors began about the escape tunnel. A few years earlier, behind the spiked Baldino fence patrolled by two identical white German shepherds, a group of workmen had appeared one morning. They hung tarpaulins over ladders to obscure what they did, and after three days, when they whisked the tarps away, there, in the middle of the lawn, stood an artificial tree trunk. It was made of cement, painted to look like bark, complete with fake knothole and two lopped limbs pointing at the sky with the fervor of amputee stubs. In the middle of the tree, a chain-sawed wedge contained a metal grill.

Paul Baldino said it was a barbecue, and we believed him. But, as time passed, we noticed that no one ever used it. The papers said the barbecue had cost $50,000 to install, but not one hamburger or hot dog was ever grilled upon it. Soon the rumor began to circulate that the tree trunk was an escape tunnel, that it led to a hideaway along the river where Sammy the Shark kept a speedboat, and that the workers had hung tarps to conceal the digging. Then, a few months after the rumors began, Paul Baldino began emerging in people’s basements, through the storm sewers. He came up in Chase Buell’s house, covered with a gray dust that smelled like friendly shit; he squeezed up into Danny Zinn’s cellar, this time with a flashlight, baseball bat, and a bag containing two dead rats; and finally he ended up on the other side of Tom Faheem’s boiler, which he clanged three times.

He always explained to us that he had been exploring the storm sewer underneath his own house and had gotten lost, but we began to suspect he was playing in his father’s escape tunnel. When he boasted that he would see the Lisbon girls taking their showers, we all believed he was going to enter the Lisbon house the same way he had entered the others. We never learned exactly what happened, though the police interrogated Paul Baldino for over an hour. He told them only what he told us. He said he had crawled into the sewer duct underneath his own basement and had started walking, a few feet at a time. He described the surprising size of the pipes, the coffee cups and cigarette butts left by workmen, and the charcoal drawings of naked women that resembled cave paintings. He told how he had chosen tunnels at random, and how as he passed under people’s houses he could smell what they were cooking. Finally he had come up through the sewer grate in the Lisbons’ basement. After brushing himself off, he went looking for someone on the first floor, but no one was home. He called out again and again, moving through the rooms. He climbed the stairs to the second floor. Down the hall, he heard water running. He approached the bathroom door. He insisted that he had knocked. And then Paul Baldino told how he had stepped into the bathroom and found Cecilia, naked, her wrists oozing blood, and how after overcoming his shock he had run downstairs to call the police first thing, because that was what his father had always taught him to do.

•

The paramedics found the laminated picture first, of course, and in the crisis the fat one put it in his pocket. Only at the hospital did he think to give it to Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon. Cecilia was out of danger by that point, and her parents were sitting in the waiting room, relieved but confused. Mr. Lisbon thanked the paramedic for saving his daughter’s life. Then he turned the picture over and saw the message printed on the back:

The Virgin Mary has been appearing in our city, bringing her message of peace to a crumbling world. As in Lourdes and Fatima, Our Lady has granted her presence to people just like you. For information call 555-MARY

Mr. Lisbon read the words three times. Then he said in a defeated voice, “We baptized her, we confirmed her, and now she believes this crap.”

It was his only blasphemy during the entire ordeal. Mrs. Lisbon reacted by crumpling the picture in her fist (it survived; we have a photocopy here).

Our local newspaper neglected to run an article on the suicide attempt, because the editor, Mr. Baubee, felt such depressing information wouldn’t fit between the front-page article on the Junior League Flower Show and the back-page photographs of grinning brides. The only newsworthy article in that day’s edition concerned the cemetery workers’ strike (bodies piling up, no agreement in sight), but that was on page 4 beneath the Little League scores.

After they returned home, Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon shut themselves and the girls in the house, and didn’t say a word about what had happened. Only when pressed by Mrs. Scheer did Mrs. Lisbon refer to “Cecilia’s accident,” acting as though she had cut herself in a fall. With precision and objectivity, however, already bored by blood, Paul Baldino described to us what he had seen, and left no doubt that Cecilia had done violence to herself.

Mrs. Buck found it odd that the razor ended up in the toilet. “If you were cutting your wrists in the tub,” she said, “wouldn’t you just lay the razor on the side?” This led to the question as to whether Cecilia had cut her wrists while already in the bath water, or while standing on the bath mat, which was bloodstained. Paul Baldino had no doubts: “She did it on the john,” he said. “Then she got into the tub. She sprayed the place, man.”

Cecilia was kept under observation for a week. The hospital records show that the artery in her right wrist was completely severed, because she was left-handed, but the gash in her left wrist didn’t go as deep, leaving the underside of the artery intact. She received twenty-four stitches in each wrist.

She came back still wearing the wedding dress. Mrs. Patz, whose sister was a nurse at Bon Secours, said that Cecilia had refused to put on a hospital gown, demanding that her wedding dress be brought to her, and Dr. Hornicker, the staff psychiatrist, thought it best to humor her. She returned home during a thunderstorm. We were in Joe Larson’s house, right across the street, when the first clap of thunder hit. Downstairs Joe’s mother shouted to close all the windows, and we ran to ours. Outside a deep vacuum stilled the air. A gust of wind stirred a paper bag, which lifted, rolling, into the lower branches of the trees. Then the vacuum broke with the downpour, the sky grew black, and the Lisbons’ station wagon tried to sneak by in the darkness.

We called Joe’s mother to come see. In a few seconds we heard her quick feet on the carpeted stairs and she joined us by the window. It was Tuesday and she smelled of furniture polish. Together we watched Mrs. Lisbon push open her car door with one foot, then climb out, holding her purse over her head to keep dry. Crouching and frowning, she opened the rear door. Rain fell. Mrs. Lisbon’s hair fell into her face. At last Cecilia’s small head came into view, hazy in the rain, swimming up with odd thrusting movements because of the double slings that impeded her arms. It took her a while to get up enough steam to roll to her feet. When she finally tumbled out she lifted both slings like canvas wings and Mrs. Lisbon took hold of her left elbow and led her into the house. By that time the rain had found total release and we couldn’t see across the street.

In the following days we saw Cecilia a lot. She would sit on her front steps, picking red berries off the bushes and eating them, or staining her palms with the juice. She always wore the wedding dress and her bare feet were dirty. In the afternoons, when sun lit the front yard, she would watch ants swarming in sidewalk cracks or lie on her back in fertilized grass staring up at clouds. One of her sisters always accompanied her. Therese brought science books onto the front steps, studying photographs of deep space and looking up whenever Cecilia strayed to the edge of the yard. Lux spread out beach towels and lay suntanning while Cecilia scratched Arabic designs on her own leg with a stick. At other times Cecilia would accost her guard, hugging her neck and whispering in her ear.

Everyone had a theory as to why she had tried to kill herself. Mrs. Buell said the parents were to blame. “That girl didn’t want to die,” she told us. “She just wanted out of that house.” Mrs. Scheer added, “She wanted out of that decorating scheme.” On the day Cecilia returned from the hospital, those two women brought over a Bundt cake in sympathy, but Mrs. Lisbon refused to acknowledge any calamity. We found Mrs. Buell much aged and hugely fat, still sleeping in a separate bedroom from her husband, the Christian Scientist. Propped up in bed, she still wore pearled cat’s-eye sunglasses during the daytime, and still rattled ice cubes in the tall glass she claimed contained only water; but there was a new odor of afternoon indolence to her, a soap-opera smell. “As soon as Lily and I took over that Bundt cake, that woman told the girls to go upstairs. We said, ‘It’s still warm, let’s all have a piece,’ but she took the cake and put it in the refrigerator. Right in front of us.” Mrs. Scheer remembered it differently. “I hate to say it, but Joan’s been potted for years. The truth is, Mrs. Lisbon thanked us quite graciously. Nothing seemed wrong at all. I started to wonder if maybe it was true that the girl had only fallen and cut herself. Mrs. Lisbon invited us out to the sun room and we each had a piece of cake. Joan disappeared at one point. Maybe she went back home to have another belt. It wouldn’t surprise me.”

We found Mr. Buell just down the hall from his wife, in a bedroom with a sporting theme. On the shelf stood a photograph of his first wife, whom he had loved ever since divorcing her, and when he rose from his desk to greet us, he was still stooped from the shoulder injury faith had never quite healed. “It was like anything else in this sad society,” he told us. “They didn’t have a relationship with God.” When we reminded him about the laminated picture of the Virgin Mary, he said, “Jesus is the one she should have had a picture of.” Through the wrinkles and unruly white eyebrows we could discern the handsome face of the man who had taught us to pass a football so many years ago. Mr. Buell had been a pilot in the Second World War. Shot down over Burma, he led his men on a hundred-mile hike through the jungle to safety. He never accepted any kind of medicine after that, not even aspirin. One winter he broke his shoulder skiing, and could only be convinced to get an X ray, nothing more. From that time on he winced when we tried to tackle him, and raked leaves one-handed, and no longer flipped daredevil pancakes on Sunday mornings. Otherwise he persevered, and always gently corrected us when we took the Lord’s name in vain. In his bedroom, the shoulder had fused into a graceful humpback. “It’s sad to think about those girls,” he said. “What a waste of life.”

The most popular theory at the time held Dominic Palazzolo to blame. Dominic was the immigrant kid staying with relatives until his family got settled in New Mexico. He was the first boy in our neighborhood to wear sunglasses, and within a week of arriving, he had fallen in love. The object of his desire wasn’t Cecilia but Diana Porter, a girl with chestnut hair and a horsey though pretty face who lived in an ivy-covered house on the lake. Unfortunately, she didn’t notice Dominic peering through the fence as she played fierce tennis on the clay court, nor as she lay, sweating nectar, on the poolside recliner. On our corner, in our group, Dominic Palazzolo didn’t join in conversations about baseball or busing, because he could speak only a few words of English, but every now and then he would tilt his head back so that his sunglasses reflected sky, and would say, “I love her.” Every time he said it he seemed delivered of a profundity that amazed him, as though he had coughed up a pearl. At the beginning of June, when Diana Porter left on vacation to Switzerland, Dominic was stricken. “Fuck the Holy Mother,” he said, despondent. “Fuck God.” And to show his desperation and the validity of his love, he climbed onto the roof of his relatives’ house and jumped off.

We watched him. We watched Cecilia Lisbon watching from her front yard. Dominic Palazzolo, with his tight pants, his Dingo boots, his pompadour, went into the house, we saw him passing the plate-glass picture windows downstairs; and then he appeared at an upstairs window, with a silk handkerchief around his neck. Climbing onto the ledge, he swung himself up to the flat roof. Aloft, he looked frail, diseased, and temperamental, as we expected a European to look. He toed the roof’s edge like a high diver, and whispered, “I love her,” to himself as he dropped past the windows and into the yard’s calculated shrubbery.

He didn’t hurt himself. He stood up after the fall, having proved his love, and down the block, some maintained, Cecilia Lisbon developed her own. Amy Schraff, who knew Cecilia in school, said that Dominic had been all she could talk about for the final week before commencement. Instead of studying for exams, she spent study halls looking up ITALY in the encyclopedia. She started saying “Ciao,” and began slipping into St. Paul’s Catholic Church on the Lake to sprinkle her forehead with holy water. In the cafeteria, even on hot days when the place was thick with the fumes of institutional food, Cecilia always chose the spaghetti and meatballs, as though by eating the same food as Dominic Palazzolo she could be closer to him. At the height of her crush she purchased the crucifix Peter Sissen had seen decorated with the brassiere.

The supporters of this theory always pointed to one central fact: the week before Cecilia’s suicide attempt, Dominic Palazzolo’s family had called him to New Mexico. He went telling God to fuck Himself all over again because New Mexico was even farther from Switzerland, where, right that minute, Diana Porter strolled under summer trees, moving unstoppably away from the world he was going to inherit as the owner of a carpet cleaning service. Cecilia had unleashed her blood in the bath, Amy Schraff said, because the ancient Romans had done that when life became unbearable, and she thought when Dominic heard about it, on the highway, amid the cactus, he would realize that it was she who loved him.

The psychiatrist’s report takes up most of the hospital record. After talking with Cecilia, Dr. Hornicker made the diagnosis that her suicide was an act of aggression inspired by the repression of adolescent libidinal urges. To each of three wildly different ink blots, she had responded, “A banana.” She also saw “prison bars,” “a swamp,” “an Afro,” and “the earth after an atomic bomb.” When asked why she had tried to kill herself, she said only, “It was a mistake,” and clammed up when Dr. Hornicker persisted. “Despite the severity of her wounds,” he wrote, “I do not think the patient truly meant to end her life. Her act was a cry for help.” He met with Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon and recommended that they relax their rules. He thought Cecilia would benefit by “having a social outlet, outside the codification of school, where she can interact with males her own age. At thirteen, Cecilia should be allowed to wear the sort of makeup popular among girls her age, in order to bond with them. The aping of shared customs is an indispensable step in the process of individuation.”

From that time on, the Lisbon house began to change. Almost every day, and even when she wasn’t keeping an eye on Cecilia, Lux would suntan on her towel, wearing the swimsuit that caused the knife sharpener to give her a fifteen-minute demonstration for nothing. The front door was always left open, because one of the girls was always running in or out. Once, outside Jeff Maldrum’s house, playing catch, we saw a group of girls dancing to rock and roll in his living room. They were very serious about learning the right ways to move, and we were amazed to learn that girls danced together for fun, while Jeff Maldrum only rapped the glass and made kissing noises until they pulled down the shade. Before they disappeared we saw Mary Lisbon in the back near the bookcase, wearing bell-bottomed blue jeans with a heart embroidered on the seat.