Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Curse of the Mistwraith»

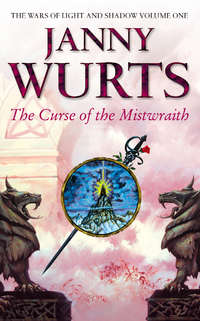

The Wars of Light and Shadow

1

Curse of the Mistwraith

Janny Wurts

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Prologue

I. CAPTIVE

II. SENTENCE

III. EXILE

IV. MISTWRAITH’S BANE

V. RIDE FROM WEST END

VI. ERDANE

VII. PASS OF ORLAN

VIII. CLANS OF CAMRIS

IX. ALTHAIN TOWER

X. DAON RAMON BARRENS

XI. DESH-THIERE

XII. CONQUEST

XIII. ETARRA

XIV. CORONATION DAY

XV. STRAKEWOOD

XVI. AUGURY

XVII. MARCH UPON STRAKEWOOD FOREST

XVIII. CULMINATION

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By Janny Wurts

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

The Wars of Light and Shadow were fought during the third age of Athera, the most troubled and strife-filled era recorded in all of history. At that time Arithon, called Master of Shadow, battled the Lord of Light through five centuries of bloody and bitter conflict. If the canons of the religion founded during that period are reliable, the Lord of Light was divinity incarnate, and the Master of Shadow a servant of evil, spinner of dark powers. Temple archives attest with grandiloquent force to be the sole arbiters of truth.

Yet contrary evidence supports a claim that the Master was unjustly aligned with evil. Fragments of manuscript survive which expose the entire religion of Light as fraud, and award Arithon the attributes of saint and mystic instead.

Because the factual account lay hopelessly entangled between legend and theology, sages in the seventh age meditated upon the ancient past, and recalled through visions the events as they happened. Contrary to all expectation, the conflict did not begin on the council stair of Etarra, nor even on the soil of Athera itself; instead the visions started upon the wide oceans of the splinter world, Dascen Elur.

This is the chronicle the sages recovered. Let each who reads determine the good and the evil for himself.

I. CAPTIVE

All for the waste of Karthan’s lands the Leopard sailed the main. s’Ilessid King then cursed s’Ffalenn, who robbed him, gold and grain.

stanza from a ballad of Dascen Elur

The longboat cleaved waters stained blood-red by sunset, far beyond sight of any shore. A league distant from her parent ship, at the limit of her designated patrol, she rose on the crest of a swell. The bosun in command shouted hoarsely from the stern. ‘Hold stroke!’

Beaten with exhaustion and the aftermath of battle, his crewmen responded. Four sets of oars lifted, dripping above waters fouled by oil and the steaming timbers of burned warships.

‘Survivors to starboard.’ The bosun pointed toward two figures who clung to a snarl of drifting spars. ‘Quick, take a bearing.’

A man shipped his looms to grab a hand compass. As the longboat dipped into the following trough, the remaining sailors bent to resume stroke. Oar shafts bit raggedly into the sea as they swung the heavy bow against the wind.

The bosun drew breath to reprimand their sloppy timing, then held his tongue. The men were tired as he was; though well seasoned to war through the feud which ran deadly and deep between Amroth and Karthan’s pirates, this had been no ordinary skirmish. Seven full-rigged warships in a fleet of seventeen had fallen before a single brigantine under the hated leopard banner. The bosun swore. He resisted a morbid urge to brood over losses; lucky, they were, to have the victory at all. The defeated brigantine’s captain had been none other than Arithon s’Ffalenn, called sorcerer and Master of Shadow.

The next swell rolled beneath the keel. Heaved and lifted on its crest, the longboat’s peaked prow momentarily eclipsed the castaways who struggled in the water. Afraid to lose sight of them, the bosun set the compassman as observer in the bow. Then he called encouragement while his oarsmen picked an erratic course through the splintered clots of planking and cordage which wallowed, treacherous as reefs upon the sea. The crew laboured in dead-faced silence. Not even the scraping bump of the corpse which passed beneath the keel caused them to alter their stroke. Horror had numbed every man left alive after the nightmare of fire, sorcery and darkness that Arithon had unleashed before the end.

The boat drew abreast of the survivors. Overtaken by a drift of wind-borne smoke, the bosun squinted through burning eyes. Only one victim looked to be conscious. He clung with whitened fingers to the nearer end of the spar, while at his back, another sailor lay lashed against the heaving pull of the waves. The knots at this one’s waist were half loosened, as if, seeing help on the way, his companion had clumsily tried to free him.

‘Ship oars!’ Gruffly, the bosun addressed the man in the water. ‘Is your friend wounded?’

The wreck victim raised listless, glassy eyes, but said nothing. Quite likely cold water had dulled the fellow’s wits. Weary of senseless ruin and the rescue of ravaged men, the bosun snapped impatiently, ‘Bring him in. We’ll get the other second, if he still breathes.’

A crewman hooked the spar with his oar shaft to steady the boat. Others leaned over the thwart to lift the half-drowned sailhand aboard.

The victim reacted with vengeful speed and doused his rescuers with seawater.

Stung nearly blind by the salt, the nearer oarsman yelled and lunged. His hand closed over a drenched mat of hair. The man in the water twisted against the restraint. He kicked clear of the spar, ducked and resurfaced, a flash of bare steel in one fist. The oarsman recoiled from him with a scream of pain and surprise, his wrist opened stark to the bone.

‘Ath, he’s Karthan’s!’ someone shouted.

The longboat’s crew erupted in confusion. Portside, those seamen within reach raised oars like clubs and retaliated. One blow, then another struck the enemy sailor’s head. Blood spilled from his nose and mouth. Chopped viciously on the shoulder, he floundered. His grasp loosened and the dagger dropped winking into the depths. Without even a curse of malediction, the Karthish sailor thrashed under, battered and finally drowned by the murderous hatred of enemies.

‘Man the oars!’ The bosun’s bellow restored order to the wildly rocking longboat. Men sank down at their benches, muttering, while seawater lapped tendrils of scarlet from the blades of the portside looms. Too tired even to curse, the officer tossed a scarf to his wounded oarsman. Then he pointed at the unconscious survivor who drifted still lashed to the spar. By now the smoke had cleared enough to see that the Karthish dog still breathed. ‘Fetch that one aboard. The king will want him for questioning, so mind you handle him wisely.’

Sailors sworn to the pirate king’s service seldom permitted themselves to be taken alive. With one casualty wrapping his wrist in the stern, no man rushed the task. Amroth’s seamen recovered the last crewman of Karthan’s brigantine from the sea with wary caution and dumped him face-down on the floorboards. The bosun regarded his prize with distaste. Barefoot, slightly built and clad in a sailhand’s patched tunic, the man seemed no one important. Only the silver ring on his left hand occasioned any notice at all; and after hours of thankless labour, the oarsmen deserved reward for their efforts.

‘Beer-booty,’ invited the bosun. He bent, caught the captive’s wrist, and tugged to pry the ring from a finger still swollen from the sea.

‘Cut ‘er free,’ suggested the crewman who nursed his slashed forearm.

Feud left no space for niceties. The bosun drew his rigging knife. He braced the captive’s hand palm upward against the stern seat, and lifted his blade to cut. That moment the longboat rocked. Dying sunlight caught and splintered in the depths of an emerald setting.

The bosun gasped. He snatched back his knife as if burned, for the ring he would steal was not silver, but white gold. The gem was carved with a leopard device, hatefully familiar.

‘Fate witness, he’s s’Ffalenn!’ Shocked and uncertain, the bosun straightened up. He had watched the enemy brigantine burn, her captain sprawled dead on her quarterdeck; but a glance at the black hair which dripped ignominiously in the bilge now belied that observation. Suddenly hand and ring were tugged from his grasp as an oarsman reached out and jerked the captive onto his back.

Bared to the fading light, the steeply-angled features and upswept browline of s’Ffalenn stood clear as struck bronze. There could be no mistake. Amroth’s seamen had taken, alive, the Master of Shadow himself.

The sailors fell back in fear. Several made signs against evil, and someone near the fore drew a dagger.

‘Hold!’ The bosun turned to logic to ease his own frayed nerves. ‘The sorcerer’s harmless, just now, or we’d already be dead. Alive, don’t forget, he’ll bring a bounty.’

The men made no response. Tense, uneasy, they shifted their feet. Someone uttered a charm against demons, and a second knife sang from its sheath.

The bosun grabbed an oar and slammed it across the thwarts between sailors and captive. ‘Fools! Would you spit on good fortune? Kill him, and our liege won’t give us a copper.’

That reached them. Arithon s’Ffalenn was the illegitimate son of Amroth’s own queen, who in years past had spurned the kingdom’s honour for adultery with her husband’s most infamous enemy. The pirate-king’s bastard carried a price on his head that would ransom an earl, and a dukedom awaited the man who could deliver him to Port Royal in chains. Won over by greed, the sailors put up their knives.

The bosun stepped back and rapped orders, and men jumped to obey. Before the s’Ffalenn bastard regained his wits, his captors bound his wrists and legs with cord cut from the painter. Then, trussed like a calf for slaughter, Arithon, Master of Shadow and heir-apparent of Karthan, was rowed back to the warship Briane. Hauled aboard by the boisterous crew of the longboat, he was dumped in a dripping sprawl on the quarterdeck, at the feet of the officer in command.

A man barely past his teens, the first officer had come to his post through wealth and royal connections rather than merit or experience. But with the captain unconscious from an arrow wound, and the ranking brass of Briane’s fighting company dead, none remained to dispute the chain of command. The first officer coped, though shouldered with responsibility for three hundred and forty two men left living, and a warship too crippled to carry sail. The bosun’s agitated words took a moment to pierce through tired and overburdened thoughts.

The name finally mustered attention.

‘Arithon s’Ffalenn!’ Shocked to disbelief, the first officer stared at the parcel of flesh on his deck. This man was small, sea-tanned and dark; nothing like the half-brother in line for Amroth’s crown. A drenched spill of hair plastered an angular forehead. Spare, unremarkable limbs were clothed in rough, much-mended linen that was belted with a plain twist of rope. But his sailhand’s appearance was deceptive. The jewel in the signet bore the leopard of s’Ffalenn, undeniable symbol of royal heirship.

‘It’s him, I say,’ said the bosun excitedly.

The crew from the longboat and every deckhand within earshot edged closer.

Jostled by raffish, excitable men, the first officer recalled his position. ‘Back to your duties,’ he snapped. ‘And have that longboat winched back on board. Lively!’

‘Aye sir.’ The bosun departed, contrite. The sailhands disbursed more slowly, clearing the quarterdeck with many a backward glance.

Left alone to determine the fate of Amroth’s bitterest enemy, the first officer shifted his weight in distress. How should he confine a man who could bind illusion of shadow with the ease of thought, and whose capture had been achieved at a cost of seven ships? In Amroth, the king would certainly hold Arithon’s imprisonment worth such devastating losses. But aboard the warship Briane, upon decks still laced with dead and debris, men wanted vengeance for murdered crewmen. The sailhands would never forget: Arithon was a sorcerer, and safest of all as a corpse.

The solution seemed simple as a sword-thrust, but the first officer knew differently. He repressed his first, wild impulse to kill, and instead prodded the captive’s shoulder with his boot. Black hair spilled away from a profile as keen as a knife. A tracery of scarlet flowed across temple and cheek from a hidden scalp wound; bruises mottled the skin of throat and chin. Sorcerer though he was, Arithon was human enough to require the services of a healer. The first officer cursed misfortune, that this bastard had not also been mortal enough to die. The king of Amroth knew neither temperance nor reason on the subject of his wife’s betrayal. No matter that men might get killed or maimed in the course of the long passage home; on pain of court martial, Briane’s crewmen must deliver the Master of Shadow alive.

‘What’s to be done with him, sir?’ The man promoted to fill the dead mate’s berth stopped at his senior’s side, his uniform almost unrecognizable beneath the soot and stains of battle.

The first officer swallowed, his throat dry with nerves. ‘Lock him up in the chartroom.’

The mate narrowed faded eyes and spat. ‘That’s a damned fool place to stow such a dangerous prisoner! D’ye want us all broken? He’s clever enough to escape.’

‘Silence!’ The first officer clenched his teeth, sensitive to the eyes that watched from every quarter of the ship. The mate’s complaint was just; but no officer could long maintain command if he backed down before the entire crew. The order would have to stand.

‘The prisoner needs a healer,’ the first officer justified firmly. ‘I’ll have him moved and set in irons at the earliest opportunity.’

The mate grunted, bent and easily lifted the Shadow Master from the deck. ‘What a slight little dog, for all his killer’s reputation,’ he commented. Then, cocky to conceal his apprehension, he sauntered the length of the quarterdeck with the captive slung like a duffel across his shoulder.

The pair vanished down the companionway, Arithon’s knuckles haplessly banging each rung of the ladder-steep stair. The first officer shut his eyes. The harbour at Port Royal lay over twenty days’ sail on the best winds and fair weather. Every jack tar of Briane’s company would be a rich man, if any of them survived to make port. Impatient, inexperienced and sorely worried, the first officer shouted to the carpenter to hurry his work on the mainmast.

Night fell before Briane was repaired enough to carry canvas. Clouds had obscured the stars by the time the first officer ordered the ship under way. The bosun relayed his commands, since the mate was too hoarse to make himself heard over the pound of hammers under the forecastle. Bone-weary, the crew swung themselves aloft with appalling lack of agility. Unbrailed canvas billowed from the yards; on deck, sailhands stumbled to man the braces. Sail slammed taut with a crash and a rattle of blocks, and the bow shouldered east through the swell. Staid as a weathered carving, the quartermaster laid Briane on course for Amroth. If the wind held, the ship would reach home only slightly behind the main fleet.

Relieved to be back under sail, the first officer excused all but six hands under the bosun on watch. Then he called for running lamps to be lit. The cabin boy made rounds with flint and striker. Briane’s routine passed uninterrupted until the flame in the aft lantern flicked out, soundlessly, as if touched by the breath of Dharkaron. Inside the space of a heartbeat the entire ship became locked in darkness as bleak as the void before creation. The rhythm of the joiners’ hammers wavered and died, replaced abruptly by shouting.

The first officer leaped for the companionway. His boots barely grazed the steps. Half-sliding down the rail, he heard the shrill crash of glass as the panes in the stern window burst. The instant his feet slapped deck, he rammed shoulder-first into the chartroom door. Teak panels exploded into slivers. The first officer carried on into blackness dense as calligrapher’s ink. Sounds of furious struggle issued from the direction of the broken window.

‘Stop him!’ The first officer’s shout became a grunt as his ribs bashed the edge of the chart table. He blundered past. A body tripped him. He stumbled, slammed painfully against someone’s elbow, then shoved forward into a battering press of bodies. The hiss of the wake beneath the counter sounded near enough to touch. Spattered by needle-fine droplets of spray, the first officer realized in distress that Arithon might already be half over the sill. Once overboard, the sorcerer could bind illusion, shape shadow and blend invisibly with the waves. No search would find him.

The first officer dived to intervene, hit a locked mass of men and felt himself dashed brutally aside. Someone cursed. A whirl of unseen motion cut through the drafts from the window. Struck across the chest by a hard, contorted body, the first officer groped blind and two-handedly hooked cloth still damp from the sea. Aware of whom he held, he locked his arms and clung obstinately. His prisoner twisted, wrenching every tendon in his wrists. Flung sidewards into a bulkhead, the first officer gasped. He felt as if he handled a careening maelstrom of fury. A thigh sledge-hammered one wrist, breaking his grasp. Then someone crashed like an axed oak across his chest. Torn loose from the captive, the first officer went down, flattened under a mass of sweaty flesh.

The battle raged on over his head, marked in darkness by the grunt of drawn breaths and the smack of knuckles, elbows and knees battering into muscle. Nearby, a seaman retched, felled by a kick in the belly. The first officer struggled against the crush to rise. Any blow that connected in that ensorcelled dark had to be ruled by luck. If Arithon’s hands remained bound, force and numbers must ultimately prevail as his guardsmen found grips he could not break.

‘Bastard!’ somebody said. Boots scuffled and a fist smacked flesh. Arithon’s resistance abated slightly.

The first officer regained his feet, when a low, clear voice cut through the strife.

‘Let go. Or your fingers will burn to the bone.’

‘Don’t listen!’ The first officer pushed forward. ‘The threat’s an illusion.’

A man screamed in agony, counterpointed by splintering wood. Desperate, the first officer shot a blow in the approximate direction of the speaker. His knuckles cracked into bone. As if cued by the impact, the sorcerer’s web of darkness wavered and lifted.

Light from the aft-running lamp spilled through the ruptured stern window, touching gilt edges to a litter of glass and smashed furnishings. Arithon hung limp in the arms of three deckhands. Their faces were white and their chests heaved like runners just finished with a marathon. Another man groaned by the chart-locker, hands clenched around a dripping shin; while against the starboard bulkhead the mate stood scowling, his colour high and the pulsebeat angry and fast behind his ripped collar. The first officer avoided the accusation in the older seaman’s eyes. If it was unnatural that a prisoner so recently injured and unconscious should prove capable of such fight, to make an issue of the fact invited trouble.

Anxious to take charge before the crew recovered enough to talk, the first officer snapped to the moaning crewman, ‘Fetch a light.’

The man quieted, scuffled to his feet and hastily limped off to find a lantern. As a rustle of returned movement stirred through the beleaguered crew in the chartroom, the first officer pointed to a clear space between the glitter of slivered glass. ‘Set the s’Ffalenn there. And you, find a set of shackles to bind his feet.’

Seamen jumped to comply. The man returned with the lantern as they lowered Arithon to the deck. Flamelight shot copper reflections across the blood which streaked his cheek and shoulder; dark patches had already soaked into the torn shirt beneath.

‘Sir, I warned you. Chartroom’s not secure,’ the mate insisted, low-voiced. ‘Have the sorcerer moved to a safer place.’

The first officer bristled. ‘When I wish your advice, I’ll ask. You’ll stand guard here until the healer comes. That should not be much longer.’

But the ship’s healer was yet engaged with the task of removing the broadhead of an enemy arrow from the captain’s lower abdomen. Since he was bound to be occupied for some time yet to come, the mate clamped his jaw and did not belabour the obvious: that Arithon’s presence endangered the ship in far more ways than one. Fear of his sorceries could drive even the staunchest crew to mutiny.

That moment one of the seamen exclaimed and flung back. The first officer swung in time to see the captive stir and awaken. Eyes the colour of new spring grass opened and fixed on the men who crowded the chartroom. The steep s’Ffalenn features showed no expression, though surely pain alone prevented a second assault with shadow. Briane’s first officer searched his enemy’s face for a sign of human emotion and found no trace.

‘You were unwise to try that,’ he said, at a loss for other opening. That the same mother had borne this creature and Amroth’s well-beloved crown prince defied all reasonable credibility.

Where his Grace, Lysaer, might have won his captors’ sympathy with glib and entertaining satire, Arithon of Karthan refused answer. His gaze never wavered and his manner stayed stark as a carving. The creak of timber and rigging filled an unpleasant silence. Crewmen shifted uneasily until a clink of steel beyond the companionway heralded the entrance of the crewman sent to bring shackles.

‘Secure his ankles.’ The first officer turned toward the door. ‘And by Dharkaron’s vengeance, stay on guard. The king wants this captive kept alive.’

He departed after that, shouting for the carpenter to send hands to repair the stern window. Barely had the workmen gathered their tools when Briane plunged again into unnatural and featureless dark. A thudding crash astern set the first officer running once more for the chartroom.

This time the shadow disintegrated like spark-singed silk before he collided with the chart table. He reached the stern cabin to find Arithon pinned beneath the breathless bulk of his guards. Gradually the men sorted themselves out, eyes darting nervously. Though standing in the presence of a senior officer, they showed no proper deference. More than a few whispered sullenly behind their hands.

‘Silence!’ Crisply, the first officer inclined his head to hear the report.

‘Glass,’ explained the mate. ‘Tried to slash his wrists, Dharkaron break his bastard skin.’

Blood smeared the deck beneath the Master. His fine fingers glistened red, and closer examination revealed that the cord which lashed his hands was nearly severed.

‘Bind his fingers with wire, then.’ Provoked beyond pity, the first officer detailed a man to fetch a spool from the hold.

Arithon recovered awareness shortly afterward. Dragged upright between the stout arms of his captors, he took a minute longer to orient himself. As green eyes lifted in recognition, the first officer fought a sharp urge to step back. Only once had he seen such a look on a man’s face, and that was the time he had witnessed a felon hanged for the rape of his own daughter.

‘You should have died in battle,’ he said softly.

Arithon gave no answer. Flamelight glistened across features implacably barred against reason, and his hands dripped blood on the deck. The first officer looked away, cold with nerves and uneasiness. He had little experience with captives, and no knowledge whatever of sorcery. The Master of Shadow himself offered no inspiration, his manner icy and unfathomable as the sea itself.

‘Show him the king’s justice,’ the first officer commanded, in the hope a turn at violence might ease the strain on his crew.

The seamen wrestled Arithon off his feet and pinioned him across the chart table. His body handled like a toy in their broad hands. Still the Master fought them. In anger and dread the seamen returned the bruises lately inflicted upon their own skins. They stripped the cord from the captive’s wrists and followed with all clothing that might conceal slivers of glass. But for his grunts of resistance, Arithon endured their abuse in silence.

The first officer hid his distaste. The Master’s defiance served no gain, but only provoked the men to greater cruelty. Had the bastard cried out, even once reacted to pain as an ordinary mortal, the deckhands would have been satisfied. Yet the struggle continued until the victim was stripped of tunic and shirt and the sailhands backed off to study their prize. Arithon’s chest heaved with fast, shallow breaths. Stomach muscles quivered beneath skin that wept sweat, proof enough that his body at least had not been impervious to rough handling.

‘Bastard’s runt-sized, for a sorcerer.’ The most daring of the crewmen raised a fist over the splayed arch of Arithon’s ribcage. ‘A thump in the slats might slow him down some.’

‘That’s enough!’ snapped the first officer. Immediately sure the sailhand would ignore his command, he moved to intervene. But a newcomer in a stained white smock entered from behind and jostled him briskly aside.

Fresh from the captain’s sickbed, the ship’s healer pushed on between sailor and pinioned prisoner. ‘Leave be, lad! Today I’ve set and splinted altogether too many bones. The thought of another could drive me to drink before sunrise.’

The crewman subsided, muttering. As the healer set gently to work with salve and bandages, the s’Ffalenn sorcerer drew breath and finally spoke.

‘I curse your hands. May the next wound you treat turn putrid with maggots. Any child you deliver will sicken and die in your arms, and the mother will bleed beyond remedy. Meddle further with me and I’ll show you horrors.’

The healer made a gesture against evil. He had heard hurt men rave, but never like this. Shaking, he resumed his work, while under his fingers, the muscles of his patient flinched taut in protest.

‘Have you ever known despair?’ Arithon said. ‘I’ll teach you. The eyes of your firstborn son will rot and flies suck at the sockets.’

The seamen tightened their restraint, starting and cursing among themselves.

‘Hold steady!’ snapped the healer. He continued binding Arithon’s cuts with stiff-lipped determination. Such a threat might make him quail, but he had only daughters. Otherwise he might have broken his oath and caused an injured man needless pain.

‘By your leave,’ he said to the first officer when he finished. ‘I’ve done all I can.’

Excused, the healer departed, and the deckhands set to work with the wire. As the first loop creased the prisoner’s flesh, Arithon turned his invective against the first officer. After the healer’s exemplary conduct, the young man dared not break. He endured with his hands locked behind his back while mother, wife and mistress were separately profaned. The insults after that turned personal. In time the first officer could not contain the anger which arose in response to the vicious phrases.

‘You waste yourself!’ After the cold calm of the Master’s words, the ugliness in his own voice jarred like a woman’s hysteria. He curbed his temper. ‘Cursing me and my relations will hardly change your lot. Why make things difficult? Your behaviour makes civilized treatment impossible.’

‘Go force your little sister,’ Arithon said.

The first officer flushed scarlet. Not trusting himself to answer, he called orders to his seamen. ‘Bind the bastard’s mouth with a rag. When you have him well secured, lock him under guard in the sail-hold.’

The seamen saw the order through with a roughness born of desperation. Watching, the first officer worried. He was a tired man with a terrified crew, balanced squarely on the prongs of dilemma. The least provocation would land him with a mutiny, and a sorcerer who could also bind shadow threatened trouble tantamount to ruin. No measure of prevention could be too drastic to justify. The first officer rubbed bloodshot, stinging eyes. A final review of resources left him hopeless and without alternative except to turn the problem of Arithon s’Ffalenn back to Briane’s healer.

The first officer burst into the surgery without troubling to knock. ‘Can you mix a posset that will render a man senseless?’

Interrupted while tending yet another wound, the healer answered with irritable reluctance. ‘I have only the herb I brew to ease pain. A heavy dose will dull the mind, but not with safety. The drug has addictive side-effects.’

The first officer never hesitated. ‘Use it on the prisoner, and swiftly.’

The healer straightened, shadows from the gimballed lantern sharp on his distressed face.

The officer permitted no protest. ‘Never mind your oath of compassion. Call the blame mine, if you must, but I’ll not sail into a mutiny for the skin of any s’Ffalenn bastard. Deliver Arithon alive to the king’s dungeons, and no man can dispute we’ve done our duty.’