Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Read My Heart: Dorothy Osborne and Sir William Temple, A Love Story in the Age of Revolution»

READ MY HEART

A Love Story in theAge of Revolution

JANE DUNN

DEDICATION

To Ellinor, Theodore, Dora –thrice blessed in you

CONTENTS

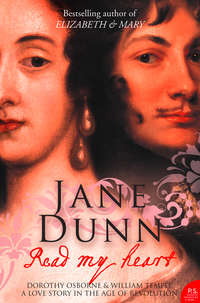

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

FAMILY TREES

THE TEMPLE FAMILY TREE

THE OSBORNE FAMILY TREE

PREFACE

1 Can There Bee a More Romance Story Than Ours?

2 The Making of Dorothy

3 When William Was Young

4 Time nor Accidents Shall not Prevaile

5 Shall Wee Ever Bee Soe Happy?

6 A Clear Sky Attends Us

7 Make Haste Home

8 Into the World

9 A Change in the Weather

10 Enough of the Uncertainty of Princes

11 Taking Leave of All Those Airy Visions

AFTERWORD

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ENDNOTES

INDEX

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES …

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A ROMEO AND JULIET

LIFE AT A GLANCE

A WRITING LIFE

ABOUT THE BOOK

GROWING UP IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

IF YOU LOVED THIS

READ ON

HAVE YOU READ

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

FAMILY TREES

THE TEMPLE FAMILY TREE

THE OSBORNE FAMILY TREE

PREFACE

‘In the seventeenth century, to be sure, Lewis the Fourteenth [Louis XIV] was a much more important person than Temple’s sweetheart. But death and time equalize all things … The mutual relations of the two sexes seem to us to be at least as important as the mutual relations of any two governments in the world; and a series of letters written by a virtuous, amiable, sensible girl, and intended for the eye of her lover alone, can scarcely fail to throw some light on the relations of the sexes.’

THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY, Essays

THE LIVES OF Dorothy Osborne and William Temple are bound together in one of the great love stories of the seventeenth century, with timeless elements that all of us, like Macaulay, recognise and share. But they also offer a personal view of their world. Against a background of civil-war destruction and family power, it is a world of letters and gardens, of friendship and scientific experiment, of international Realpolitik fraught with the treachery of princes. We only know their story because of a terrific piece of good luck. Seventy-seven letters written by Dorothy to William during their long clandestine courtship survive. Throughout we hear Dorothy’s voice, flirtatious, politically canny, philosophical and overflowing with feeling. ‘Love is a Terrible word,’ she wrote to William, ‘and I should blush to death if anything but a letter accuses me on’t.’ Into their letters went all the thoughts and emotions too difficult or dangerous to say in person and their honesty and the details of their lives open up a shaft of light on this period, this man, this woman.

Intelligent, eloquent, unalike, Dorothy and William recreate their world through letters, romances and essays in which their humour and humanity dissolve the barriers of time and circumstance to bring them both to life again. What is more, they lived through one of the most eventful centuries of British history, marked with both bloody and peaceful revolutions. The age is illuminated through the contrasting experiences of these two gentry families, the Osbornes indomitably royalist and the Temples more pragmatically parliamentarian – but open to offers. Dorothy and William faced hardships and reversals, resisted family threats and blackmail, and in the end triumphed over all, even the spectre of illness and death, to marry at last. William went on, in the reign of Charles II, to become a fluent and engaging essayist, an innovative gardener and a celebrated diplomat, with Dorothy so actively engaged at his side that she was termed ‘Lady Ambassadress’.

All this contributes to the appeal of their story. But nothing of their love affair would be known in any detail if these letters had not survived, and it is William, unable to bring himself to destroy them as the lovers had agreed to do, in a desperate attempt to evade detection, who ensures their love a lasting memorial. There was initially a larger hoard, so much so that Dorothy wondered what William meant to do with all her letters, joking he had ‘enough to load a horse’. It is possible that the majority were destroyed by a protective granddaughter in the more circumspect eighteenth century. What remain, however, represent the last two years of a six-and-a-half-year courtship and were recognised by William and then his sister Martha as wonderful literary creations, and, even then, worthy of publication. These seventy-seven letters and a few later notes were saved, wrapped in bundles and stored in a special cabinet, still in the possession of the Osborn family.

Over crisp sheets of paper Dorothy’s elegant cursive hand wrote in measured loops and curlicues of everything that mattered to her, from her deepest hopes and feelings to shopping requests and the gossip of the neighbourhood. Letters were the only means of communication between them, and on to paper she and William poured all their pent-up emotion, their covert rebellion against family and the thrill of exploring philosophical and political ideas. These love letters were not only powerful tools of seduction but also revealing of the lovers themselves in the continual ebb and flow of conversation.

But history rolled on and although William’s celebrity for a while did not fade, Dorothy and her story remained silent, known only to her descendants who guarded the letters, recognising their extraordinary quality, until the Victorians discovered her and fell in love. There is no other word for the emotion she aroused in fine intellectual Victorian gentlemen such as the great historian and essayist Thomas Babington Macaulay, William’s first biographer the Right Honourable Thomas Peregrine Courtenay, and the first editor of Dorothy’s letters Edward Abbott Parry. All these men declared themselves to be among her ‘servants’, i.e. suitors for her hand.

Courtenay first brought Dorothy to public gaze when he incorporated part of forty-two of her letters in his biography of William, Memoirs of the Life, Works and Correspondence of Sir William Temple, published in 1836. It was in a lengthy essay review that Macaulay revealed his own tenderness for the Dorothy of the letters. His description of her character as he saw it, however, showed more his own prejudices: ‘She is said to have been handsome; and there remains abundant proof that she possessed an ample share of the dexterity, the vivacity and the tenderness of her sex.’

Though enchanted by the letters, this lofty Victorian still managed to underestimate their great literary and historical value, and patronised the author while he praised her: ‘Her own style is very agreeable; nor are her letters at all the worse for some passages in which raillery and tenderness are mixed in a very engaging namby-pamby.’

The young barrister Edward Abbott Parry, later to be a judge and knighted, was equally enchanted by the Dorothy who emerged from the shadows in her husband’s biography. After publishing his own essay on her he was contacted by the Longe family, descendants of Dorothy’s and keepers of her papers, and given permission to edit a book of the letters the family had guarded for so long. Parry’s edition of seventy of the letters, Letters from Dorothy Osborne to Sir William Temple 1652–54, was published in 1888 and enjoyed an immediate success. One anonymous reviewer in Temple Bar expressed a general consensus in hailing, ‘a most loveable portrait of a charming and high-souled woman, who possessed strong common sense, the clearest judgement and a keen sense of humour’. These seventy letters were bought by the British Museum in 1891 (an extra seven seem to have been retained by the family) and many published editions of her letters followed, the later ones incorporating all seventy-seven. My husband Nick Ostler, ever a truffle-hunting boar when it comes to second-hand bookshops, turned up one of these editions in Padstow in Cornwall and immediately my fascination with Dorothy and William and their life began.

To my surprise there has never been a biography of Dorothy Osborne, apart from an elegant but soft-centred essay by Lord David Cecil in his book about her and Thomas Gray, Two Quiet Lives. Dorothy, nevertheless, has become famous in the history of English literature as an early and brilliant exponent of the epistolary art, but her complex personality and the extraordinary adventures of her life – if they have been mentioned at all – are used merely as context for her letters.

William has been better served, his life more public, his achievements recognised in the world of men. There have been a few biographies of him, most notably the first by the Victorian Courtenay and a judicious and comprehensive modern life published by Homer E. Woodbridge in 1940. They inevitably concentrated on the man, his ideas and diplomatic career, with Dorothy very much off-stage as the silent supportive spouse. In fact it was a marriage of intellectual equals, as Dorothy had always intended it should be, and as the more egalitarian Dutch fully recognised when William was ambassador there: it is more interesting and truthful, to my mind, to place them side by side and attempt to write about their lives together.

There are few female voices that call to us from the early seventeenth century and no one has been more full of character, or more conversationally present as we read her words than Dorothy Osborne. William’s letters and essays also are so seemingly modern in their frankness and informality, his confiding voice draws us into his life while revealing his warmth and easy charm. His literary style was held up as exemplary for at least two centuries after his death: he was considered by many to be the best essayist of the restoration after Dryden. Dr Johnson credited William with being the first writer to bring cadence to English prose and Charles Lamb wrote an essay commending his ability to mimic casual conversation, ‘his plain natural chit-chat’ as if from an easy chair, while sharing nuggets of information and inventive speculations that effortlessly informed and entertained his readers.

Editions of Dorothy’s letters and William’s essays were found in every good literary library during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The distinguished poet Peter Porter, inspired by Dorothy’s letters, wrote the poems for a song cycle composed by Nicholas Maw, The Voice of Love.* But in subsequent years they have slipped from view. Dorothy and William’s re-emergence into public consciousness is well overdue: their love story is timeless, and the period of revolutions and unrest in which they played their part resonates with the preoccupations and political shifts today.

Dorothy Osborne and William Temple grew up during the British civil wars. They were fifteen and fourteen respectively when Charles I raised his standard at Nottingham in 1642, heralding the beginning of the greatest political and social turmoil in the nation’s history. They were still only twenty-one and twenty when the king was executed in January 1649. In recent times the suffering of the Serbs and Croats as Yugoslavia turned on itself brings something of the domestic terror of civil wars home to us now. But nineteenth-century critics, who discovered Dorothy Osborne through her letters, liked to see her as the embodiment of English life, womanly discretion and the national virtues of stoicism, humour and keeping up appearances. Even Virginia Woolf recalls Dorothy’s memory to bolster a moment of awe at the continuity of rural life, remembering a delightful passage in one of Dorothy’s letters where she describes an afternoon spent with local shepherdesses in the fields.

But civil war touched everyone and destroyed more than flesh and stone. Trust and hope for the future were also casualties in this most pernicious of conflicts. William Temple’s family were parliamentarians, although William seemed to be at ease on either side of the ideological divide. The Osborne family, as steadfast royalists, suffered far greater depredation. Their fortunes were wasted, two sons killed and the parents’ health destroyed.

The civil wars stamped a heavy footprint on the impressionable years of their youth. Both Dorothy Osborne and William Temple grew to adulthood in a country at war with itself. But when the old regimes are lost, there is everything to play for in the creation of the new. They took their places on the world stage during Charles II’s reign, attempting to promote peace and prosperity by building strong bonds with the Dutch, the most successful mercantile nation of the age. With William away, Dorothy and their family also lived through the terror of the Great Plague in London which, to everyone’s horrified disbelief, was followed by the Great Fire that destroyed much of the city, for a while appearing to be an outrageous act of international terrorism. William and Dorothy played a crucial role in one of the most important alliances in that rebellious century – the marriage of William of Orange with Mary, James II’s daughter, whose claim to the throne would make possible the remarkable Glorious Revolution of 1688 that finally secured the nation’s religion as Protestant with William and Mary on the throne.

William and Dorothy both lived to old age and died in their own beds, having survived smallpox, plague and the deaths of all nine children before them. They had lived honourably and well, as the confidants of princes, queens and kings, but had been concerned too for their servants and for the sailors, soldiers and yeomen who made the country work. In the end, William was a better man than diplomat: sent to lie abroad for his country he would not compromise his personal principles and refused to do his monarch’s dirty work. His career began with meteoric ascent, but lacking the propellant of ambition it fell to earth, where he was happiest. There in his gardens and library, in the midst of family and friends he reflected on life and looked outwards to the world. Their happy domestic life allowed him and Dorothy to endure the tragedies that befell them, seeking solace from their friends, their reading and writing, the revolving gardening year and the good fortune that had come their way.

During their rollercoaster courtship and prolonged exile from each other, Dorothy returned time and again to the poignant question, ‘shall wee ever bee soe happy?’ – as happy as they longed to be. She assured William it was just the intensity of her love that made her fearful: ‘I love you more than Ever, and tis that only gives mee these dispaireing thoughts.’ But in hindsight there are two answers to her question. Yes – because against all the odds they did marry at last, and there could be no more satisfactory consummation than that. And yet no, too – because contemplating their lives together, as they did, as an epic romance that could only end with twin souls transmuted into one, would always be a happier state than the reality of the world.

Through letters and memoirs their words draw us into their lives and illuminate the extraordinary times in which they lived: ‘Read my heart,’ Dorothy wrote as she laid her hopes before him and William too claimed his writing to her was ‘a vent for [my feelings] and shewd you a heart wch you have so wholly taken up’. Their clear voices tell us the story of that grand romance of thwarted passion, conniving families, ridiculous acquaintances, disease and disappointments, together with major political achievements and the fulfilment of love – all lived out in an age of revolution.*

* The first performance was given in 1966 at Goldsmith’s Hall, London, with the mezzo-soprano Janet Baker singing as Dorothy with the refrain ‘Shall we ever be so happy?’

* I hope my use of footnotes in the pages that follow will illuminate rather than distract from the story. There are so many fascinating bit players on this stage I could not allow them to crowd the narrative in their full distinction but equally was loath to let them pass without note.

CHAPTER ONE

Can There Bee a More Romance Story Than Ours?

All Letters mee thinks should bee free and Easy as ones discourse not studdyed, as an Oration, nor made up of hard words like a Charme

DOROTHY OSBORNE [to William Temple, September 1653]

as those Romances are best whch are likest true storys, so are those true storys wch are likest Romances

WILLIAM TEMPLE [to Dorothy Osborne, c.1648–50]

THE ROMANCE BEGAN in the dismal year of 1648. It was much wetter than usual with an English summer full of rain. The crops were spoiled, the animals sickened ‘and Cattell died of a Murrain everywhere’.1 The human population had fared no better. The heritage of Elizabeth I’s reign had been eighty years of peace, the longest such period since the departure of the Romans over twelve centuries before. After this, the outbreak of civil war in 1642 had come as a severe shock. Few had remained unscathed. By the time the crops failed in 1648, the first hostilities of the civil war were over but the bitterness remained. The nightmare of this domestic kind of war was its indistinct firing lines and the fact the enemy was not an alien but a neighbour, brother or friend. The rift lines were complex and deep. Old rivalries and new opportunism added to the murderous confusion of civil war. Waged in the name of opposing interests and ideologies, the pitiful destruction and its bitter aftermath were acted out on the village greens and town squares, in the demesnes of castles and the courtyards of great country houses.

One of the many displaced by war was the young woman, Dorothy Osborne. She was twenty-one and in peaceful times would have been cloistered on her family’s estate in deepest Bedfordshire awaiting an arranged marriage with some eligible minor nobleman or moneyed squire. Instead, she was on the road with her brother Robin, clinging to her seat in a carriage, lurching on the rutted track leading southwards on the first leg of a journey to St Malo in France, where her father waited in exile. Low-spirited, disturbed by the catastrophes that had befallen her family, Dorothy could not know that the adventure was about to begin that would transform her life.

Dorothy’s family, the Osbornes of Chicksands Priory near Bedford, was just one of the many whose lives and fortunes were shaken and dispersed by this war. At its head was Sir Peter Osborne, a cavalier gentleman who had unhesitatingly thrown in his lot with the king when he raised his standard at Nottingham in August 1642. Charles’s challenge to parliament heralded the greatest political and social turmoil in his islands’ history. And Sir Peter, along with the majority of the aristocracy and landed gentry, took up the royalist cause; in the process he was to lose most of what he held dear.

Dorothy was the youngest of the Osborne children, a dark-haired young woman with sorrowful eyes that belied her sharp and witty mind. When war first broke out in 1642 she was barely fifteen and her girlhood from then on was spent, not at home in suspended animation, but caught up in her father’s struggles abroad or as a reluctant guest in other people’s houses. After the rout of the royalist armies in the first civil war, the Osborne estate at Chicksands was sequestered: the family dispossessed was forced to rely on the uncertain hospitality of a series of relations. Being the beggars among family and friends left Dorothy with a defensive pride, ‘for feare of being Pittyed, which of all things I hate’.2

By 1648 two of her surviving four brothers had been killed in the fighting, and circumstances had robbed her of her youthful optimism. Her father had long been absent in Guernsey. He had been suggested as lieutenant governor for the island by his powerful brother-in-law Henry Danvers, Earl of Danby, who had been awarded the governorship for life. To be a royalist lieutenant governor of an island that had declared for the parliamentarians was a bitter fate and Sir Peter and his garrison ended up in a prolonged siege in the harbour fortress of Castle Cornet, abandoned by the royalist high command to face sickness and starvation. Dorothy, along with her mother and remaining brothers, was actively involved in her father’s desperate plight and it was mainly the family’s own personal resources that were used to maintain Sir Peter and his men in their lonely defiance.

Camped out in increasing penury and insecurity at St Malo on the French coast, his family sold the Osborne silver and even their linen in attempts to finance provisions for the starving castle inmates. When their own funds were exhausted, Lady Osborne turned to solicit financial assistance from relations, friends and reluctant officials. Often it had been humiliating and unproductive work. Dorothy had shared much of her mother’s hardships in trying to raise funds and both had endured the shame of begging for help. These years of uncertainty and struggle took their toll on everyone.

Dorothy’s mother, never the most cheerful of women, had lost what spirits and health she had. She explained her misanthropic attitude to her daughter: ‘I have lived to see that it is almost impossible to believe people worse than they are’; adding the bitter warning, ‘and so will you.’ Such a dark view of human nature expressed forcefully to a young woman on the brink of life was a baleful gift from any mother. Lady Osborne also criticised her daughter’s naturally melancholic expression: she considered she looked so doleful that anyone would think she had already endured the worst tragedy possible, needing, her mother claimed, ‘noe tear’s to perswade [show] my trouble, and that I had lookes soe farr beyond them, that were all the friends I had in the world, dead, more could not bee Expected then such a sadnesse in my Ey’s’ [she could not look any sadder].3

So it was that this young woman, whose life had already been forced out of seclusion, set out with her brother Robin in 1648 for France. Dorothy recognised the change these hardships had wrought, how pessimistic and anxious she had become: ‘I was so alterd, from a Cheerful humor that was always’s alike [constant], never over merry, but always pleased, I was growne heavy, and sullen, froward [turned inward] and discomposed.’4 She had little reason to expect some fortunate turn of fate. More likely was fear of further loss to her family, more danger and deaths and the possibility that their home would be lost for ever.

An arranged marriage to some worthy whose fortune would help repair her own was the prescribed goal for a young woman of her class and time. Dorothy had grown up expecting marriage as the only career for a girl, the salvation from a life of dependency and service in the house of some relation or other. But it was marriage as business merger, negotiated by parents. Love, or even liking, was no part of it, although in many such marriages a kind of devoted affection, even passion, would grow. She struggled to convince herself it was a near impossibility to marry for love: ‘a happiness,’ she considered, ‘too great for this world’.5

Dorothy, however, had been exposed also to the more unruly world of the imagination. She was a keen and serious reader. She immersed herself in the wider moral and emotional landscapes offered by the classics and contemporary French romances, most notably those of de Scudéry. These heroic novels of epic length, sometimes running to ten volumes, enjoyed extraordinary appeal during the mid-seventeenth century. Some offered not just emotional adventure but also the delights of escapism by taking home-based women (for their readers were mostly female) on imaginary journeys across the known world.

Despite having her heart and imagination fired with fables of high romance, Dorothy knew her destiny as an Englishwoman from the respectable if newly impoverished gentry lay in a grittier reality. As she and her brother passed through their own war-scarred land they were faced by the hard truth that the conflict was not yet over and the country was becoming an increasingly disorderly and lawless place. Traditions of accepted behaviour and expectation were upended. Authority, from the local gentry landowners to the king, had been fundamentally challenged and law and order were beginning to crumble. Travelling was dangerous at any time, for the roads were rutted tracks and travellers were vulnerable to desperate or vicious men. There was no police force, and justice in a time of war was random and largely absent. In her memoirs Lady Halkett,* a contemporary of Dorothy’s, noted the increase in unprovoked acts of murderous sectarian violence against individuals: ‘there was too many sad examples of [such] att that time, when the devission was betwixt the King and Parliament, for to betray a master or a friend was looked upon as doing God good service.’6

Dorothy recalled later the self-imposed tragedy, witnessed at first hand, of what had become of England, ‘a Country wasted by a Civill warr … Ruin’d and desolated by the long striffe within it to that degree as twill bee usefull to none’.7 Certainly her family’s fortunes and future prospects appeared to be as ruined as the burned houses and dying cattle they passed on their journey south. However destructive civil war was to life, fortune and security, the social upheavals broke open some of the more stifling conventions of a young unmarried woman’s life. Although exposing her to fear and humiliation, the struggle to save her father propelled Dorothy out of Bedfordshire into a wider horizon and a more demanding and active role in the world.

Now she was on the road again: however disheartening the reasons for her journey, whatever the dangers, she was young enough to rise to this newfound freedom and the possibility of adventure. The bustling activity of other travellers was always interesting, the unpredictability of experience exhilarating to a highly perceptive young woman: for Dorothy the small dramas of people’s lives were a constant diversion. She shared her amusement with her brother Robin on the journey, possibly making similar comments to the following, when she noted the extraordinary diminishment wrought by marriage on a male acquaintance whom she had thought destined for greater things. It is as if she is talking to us directly, confiding this piece of mischievous gossip to an inclined ear:

I was surprised to see, a Man that I had knowne soe handsom, soe capable of being made a pretty gentleman … Transformed into the direct shape of a great Boy newly come from scoole. To see him wholly taken up with running on Errand’s for his wife, and teaching her little dog, tricks, and this was the best of him, for when hee was at leasure to talke, hee would suffer noebody Else to doe it, and by what hee sayd, and the noyse hee made, if you had heard it you would have concluded him drunk with joy that hee had a wife and a pack of houndes.8

Dorothy’s analytic, philosophical turn of mind always searched for deeper significance as well as humour in the antics of her fellows. Her conversational letters, full of irony and gossip, showed her striving to do right herself and yet highly entertained by the wrongs done by others. As Dorothy and Robin crossed by ferry to the Isle of Wight to await the boat to France there was much to watch and wonder at. When they eventually arrived at the Rose and Crown Inn they had the added piquancy of being close to the forbidding Norman fortress, Carisbrooke Castle, where Charles I was imprisoned, with all the attendant speculation around his recent incarceration and various attempts at escape and rescue.

Also en route to France was a young man of quite extraordinary good looks and ardent nature. William Temple was only twenty and had evaded most of the bitter legacies and depredations of the civil war. His family were parliamentarians, his father sometime Master of the Rolls in Ireland and a member of parliament there. William was his eldest son and although not dedicated to scholarship was highly intelligent and curious about the world, with an optimistic view of human nature. His easy manners, interest in others and natural charm were so infectious that his sister Martha claimed that on a good day no one, male or female, could resist him. Sent abroad by his father to broaden his education and protect him from the worst of the war at home, William Temple, naturally independent-minded and tolerant, avoided playing his part in the sectarianism that divided families and destroyed lives.

There was nothing, after all, to keep him at home, as his sister later explained: ‘1648 [was] a time so dismal to England, that none but those who were the occasion of those disorders in their Country, could have bin sorry to leave it.’9 William headed first for the Isle of Wight to visit his uncle Sir John Dingley who owned a large estate there. He had another more controversial family member on the island, his cousin Colonel Robert Hammond,* who as the governor of Carisbrooke Castle had the unenviable task of keeping the defeated king confined.