Czytaj tylko na Litres

Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

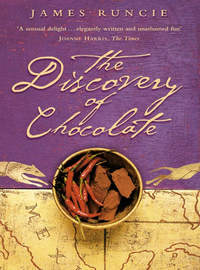

Czytaj książkę: «The Discovery of Chocolate: A Novel»

Coś poszło nie tak, spróbuj ponownie później

8,68 zł

Gatunki i tagi

Ograniczenie wiekowe:

0+Data wydania na Litres:

28 grudnia 2018Objętość:

231 str. 2 ilustracjiISBN:

9780007406906Właściciel praw:

HarperCollins