Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Resurrectionist»

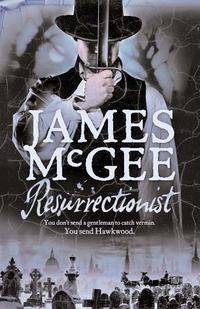

JAMES McGEE

Resurrectionist

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Historical Note

Keep Reading

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

When he heard the sobbing, Attendant Mordecai Leech’s first thought was that it was probably the wind trying to burrow its way under the eaves. On a night such as this, with rain lashing the windows like grapeshot, it was not an unusual occurrence; the vast building was old and draughty and had been condemned years ago. Only as Leech turned the corner at the foot of the broad stairway leading to the first floor, candle held aloft, did he realize that the weeping was not emanating from outside the building but from one of the galleries on the landing above him.

The galleries were long with high, arched ceilings and sound had a tendency to travel, so it was hard to tell the exact source of the distress, or even whether the sufferer was male or female.

Probably the bloody American, Norris, Leech thought, as another low moan drifted down the stairwell. It was followed by a long-drawn-out howl, like that made by a small dog. Judging from the intensity of the ululation, it sounded as if the poor bastard was in mortal torment, in the throes of another of his regular nightmares. But then, Leech reflected in a rare moment of compassion, if I were chained to the bloody wall by my neck and ankles, I’d probably be suffering bad dreams too.

The howl gave way to a keening wail and Leech cursed under his breath. The ruckus was liable to disturb the wing’s other inhabitants, and once they’d picked up the din and joined in it would sound like feeding time at the Tower menagerie, which was a guarantee that no one would get a wink of sleep. God rot the mad bastard!

Reluctantly, Leech prepared to mount the stairs, only to be startled by the harsh jangle of a bell. Suddenly he remembered that was why he’d come downstairs in the first place – in answer to a summons from someone outside, requesting admittance. Leech reached into his jacket pocket and consulted his watch. It was a little after ten o’clock. He didn’t need to look through the inspection hatch to see who it was.

As he was reaching for the bolts on the inside of the door, Leech noticed that the wailing had stopped. It was as if the sound of the bell had triggered the silence. He breathed a sigh of relief. Maybe it would be a quiet night after all.

The door swung inwards to reveal a slender figure dressed in a black, rain-sodden cloak and wide-brimmed hat, dripping with water. A woollen scarf, wrapped round the visitor’s neck and lower face as a protection against the inclement weather, hid his features.

Leech stood aside to let the man enter. “Ev’ning, Reverend,” he whispered. “I was wondering if the bloody rain would keep you away. Beggin’ your pardon,” Leech added hurriedly. His voice remained low, as if he was afraid he might be overheard. Members of the clergy were not welcome here. That was the rule, by order of the governors.

The clergyman untied his scarf, revealing his clerical collar, and lifted his head. “I was detained; a burial service for one of my parishioners and a host of other duties, I’m afraid.”

In raising his head and thus elevating the brim of his hat, the clergyman’s countenance was revealed. It was neither a young nor an old face. But there was wisdom there, in the eyes and the crow’s feet and the deep furrows etched into the cheeks and forehead. There were several scars, too, along the jawline: small and round, hinting at a brush with some variation of the pox. High along the priest’s right cheekbone what looked suspiciously like a wound from a blade had created a shallow runnel.

Leech had often wondered about the scar and the priest’s background, but he had been too wary to ask the man directly and no one he had mentioned it to knew the circumstances of the disfigurement; or, if they did know, they chose not to impart information on the subject. So Leech remained ignorant and more than a mite curious.

The priest removed his hat and cloak and shook them to expel the rain. “How is he?”

Leech shrugged. “Wouldn’t know, Reverend. I don’t have a lot to do with ’im. You probably see more of ’im than I do. I make sure ’is door’s bolted and that he gets ’is victuals, an’ that’s as much as I ’as to do with it. An’ that suits me just fine. Anything else, you’d be better askin’ the apothecary. How long’s it been since you’ve seen ’im?”

“We played our last game a week ago. I was soundly beaten, I’m afraid. His command of strategy is quite formidable and, alas, I was rather a poor adversary. However, he was exceedingly magnanimous in victory.” The priest patted Leech’s arm. “Let us hope this evening’s contest proves more rewarding.”

Another low moan drifted down from on high and the keeper tensed. “Buggeration. Er … sorry, Reverend.”

The slam of a metal door from deeper inside the building echoed through the darkened wing. It was followed by the sound of heavy footsteps and an angry warning. “God damn it, Norris! If you don’t keep it down, I’ll be in there tightening the bloody screws!”

As if at a given signal, the threat was answered by an uneven chorus of raised voices in varying degrees of excitement. This was followed, in quick succession, by a cacophony of high-pitched screams, a peal of hysterical laughter and, somewhat incongruously, what sounded like the opening chant of some religious exultation.

“Hell’s bleedin’ bells!” Leech spat. “That’s gone and done it.”

The priest shook his head. “Poor demented souls.”

Poor souls, my arse, Leech muttered under his breath. Aloud, he said, “Come on, Reverend, I’ll take you to him. Quickly now, stay close to me. And I’d be obliged if you’d put your ’at back on and keep your scarf high. Don’t want any pryin’ eyes spottin’ your collar. Wouldn’t want either of us to get into trouble.” The attendant jerked a thumb skywards. “Then I can go and help deal with that lot upstairs.”

Casting a wary eye around him, Leech turned and led the way along the dimly lit corridor. The priest hurried in his wake. Gradually, the noise from the first floor began to recede as they left the stairs behind them.

Not for the first time, the priest was struck by the speed at which decay was spreading through the building. There were wide cracks along the edges of the ceiling. Rainwater was running down the walls in streams. Many of the window frames were so far out of alignment it was clear that some sections of the roof were too heavy for the bowed walls to support. The entire edifice was crumbling into the ground.

Leech turned the corner. Ahead of them a long corridor led off into stygian darkness. A blast of rain splattered loudly against a nearby window. The sound was accompanied by a groan like that of an animal in pain.

Leech grinned at the priest’s startled expression. “Don’t worry, Reverend, it’s only the rafters. Used to be in the navy,” the attendant added, “I knows a bit about ship building. Got to give the ribs room to breathe. Same with this place. Mind you, the stupid buggers only went and built her on top of the city ditch, didn’t they? Know what we’re standing on? About six inches o’ rubble. Below that there’s naught but bleedin’ soil. We ain’t just leakin’, we’re bloody sinkin’ as well!” Leech looked up. “Anyways, we’re here.”

They were standing in front of a solid wooden door. Set into the door at eye level was a small, six-inch-square grille, similar to the screen in a confessional. At the base of the door there was a gap, just wide enough to admit a food tray. Both the grille and the gap were silhouetted by the pale yellow glow of candlelight emanating from inside the room.

Leech reached for the key ring at his waist.

“You know what to do, Reverend. Pull on the bell as usual. It’ll ring in the keepers’ room. I’ll be off at midnight, unless the buggers upstairs are still awake, but old Grubb’ll be on duty. He’ll be waitin’ to unlock the door and see you out.”

The priest nodded.

Leech gave the door a wary eye. “You’ll be all right?”

The priest smiled. “I’ll be perfectly safe, Mr Leech, but thank you for your concern.”

Leech rapped the key ring on the door and placed his mouth against the metal grille. “Visitor for you. The Reverend’s here.”

Leech waited.

“You may enter.” The voice was male. The soft-spoken words were measured and precise. There was something vaguely seductive in the tone of the invitation that caused the short hairs on the back of Mordecai Leech’s neck to prickle uncomfortably. Slightly unnerved by the sensation, though he wasn’t sure why, the keeper unlocked the door, pushed it open, and stepped back.

In the corner of the room, a shadowy figure rose and moved slowly towards the light.

The priest stepped over the threshold. Leech closed and locked the door, then waited, head cocked, listening.

“Good evening, Colonel.” The priest’s voice. “How are you this evening?”

The reply, when it came, was low and indistinct. Leech tipped his ear closer to the door but the conversation was already fading as the occupants moved away into the room.

Leech stood listening for several seconds then, realizing that it was pointless, he turned on his heel and made his way back down the corridor. As he approached the stairwell his ears picked up the sounds of discordant singing and he groaned. Sounded as if they were still at it. It was going to be a long night.

Half an hour after midnight, the bell rang in the keepers’ room. Amos Grubb sighed, wrapped the blanket around his bony shoulders, and reached for the candle-holder. Attendant Leech had warned him to expect the summons. Even so, Grubb felt a stab of resentment that he should have to vacate his lumpy mattress in order to answer the call. The wing was quieter now, after the recent disturbance. It was quite astonishing the effect a bit of laudanum could have on even the most obstinate individual. One small drop in a beaker of milk and Norris was sleeping like a baby. Most of the others, nerves soothed by the resulting calm, had swiftly followed suit. A few were still awake, snuffling and whispering either among or to themselves, but it was relatively peaceful, all things considered. Even the rain had eased, though the wind was still whistling through the gaps around the window frames.

It was bitterly cold. Grubb shivered. He’d been hoping to get his head down for a few hours before making his early-morning rounds. Still, once the visitor was on his way, Grubb thought wistfully, he could look forward to his forty winks with a clear conscience.

The elderly attendant swore softly as he squelched his way along the passage.

He halted outside the locked door and rattled the keys against the grille.

There was the sound of a chair sliding back and the murmur of voices from within.

Grubb unlocked the door and stepped away, holding his candle aloft. “Ready when you are, Reverend.”

Grubb saw that the priest was already wearing his cloak. He’d donned his hat and scarf, too. The clergyman turned on the threshold. “Goodbye, Colonel, my thanks for a most convivial evening. And very well played, though I promise I’ll give you a good run next time,” he said, wagging an admonishing finger.

Stepping through the door, the priest drew himself tightly into his cloak and waited as Grubb secured the door behind him.

Together, they set off down the passage. Grubb led the way, candle held at waist height, on the hunt for puddles. He was conscious of the priest padding along at his side and glanced over his shoulder, trying to steal a look at the clergyman’s face. Leech had asked him about the scars a month or two back. Grubb had confessed his ignorance and was as curious as his colleague to learn their origin. He couldn’t see much in the gloom. The priest’s head was still bowed as he concentrated on watching his footing, his face partially obscured beneath the lowered hat brim, but Grubb could just make out the scars along the edge of the jaw. The attendant’s eyes searched for the jagged weal across the priest’s right cheek. There it was. It looked different somehow, more inflamed than usual, as though suddenly suffused with blood.

As if aware that he was being studied, the priest glanced sideways and Grubb felt the breath catch in his throat. The priest’s eyes were staring directly into his. The obsidian stare made Grubb blanch and lower his gaze. The old attendant sensed the priest raise the scarf higher across his face, as if to repel further examination.

Wordlessly, Grubb led him to the front hall and waited as the clergyman adjusted his hat. Then he unlocked the door.

Across the courtyard, almost obscured beyond the veil of drizzle, Grubb could just make out the entrance columns and the high main gates.

“Can you see your way, Reverend, or would you like me to fetch a lantern?”

The priest stepped out into the night then paused, his head half turned. When he spoke, his voice was muffled. “Thank you, no. I’m sure I can find my way. No need for both of us to catch our death. Good night to you, Mr Grubb.” He set off across the courtyard, head bent.

Grubb stared after him. The priest looked like a man in a hurry, as if he couldn’t wait to leave. Not that Grubb blamed him. The place had that sort of effect on visitors, particularly those who chose to come at night.

The priest vanished into the murk and Grubb secured the door. He cocked his head and listened.

Silence.

Amos Grubb drew his blanket close and mounted the stairs in search of warmth and slumber.

It was the pot-boy, Adkins, who discovered that the food tray had not been touched. An hour had passed since it had been placed in the gap at the bottom of the door, and the two thin slices of buttered bread and the bowl of watery gruel were still there. Adkins reported the oddity to Attendant Grubb, who, shrugging himself into his blue uniform jacket, went to investigate, keys in hand.

Adkins wasn’t wrong, Grubb saw. It was unusual for food to be ignored, given the long gap between meal times.

Grubb banged his fist on the door. “Breakfast time, Colonel! And young Adkins is here to take your slops. Let’s be having you. Lively now!”

Grubb tried to recall what time the colonel’s visitor had left the previous evening. Then he remembered it hadn’t been last night, it had been early this morning. Perhaps the colonel was in his cot, exhausted from his victory at the chessboard, although that would have been unusual. The colonel was by habit an early riser.

Grubb tried again but, as before, his knocking drew no response.

Sighing, the keeper selected a key from the ring and unlocked the door.

The room was dark. The only illumination came courtesy of the thin, desultory slivers of light filtering through the gaps in the window shutters.

Grubb’s eyes moved to the low wooden-framed cot set against the far wall.

His suspicions, he saw, had been proved correct. The huddled shape under the blanket told its own story. The colonel was still abed.

All right for some, Grubb thought. He shuffled across to the window and opened the shutters. The hinges had not been oiled in a while and the rasp of the corroding brackets sounded like nails being drawn across a roof slate. The dull morning light began to permeate the room. Grubb looked out through the barred window. The sky was grey and the menacing tint indicated there would be little warmth in the day ahead.

Grubb sighed dispiritedly and turned. To his surprise the figure under the blanket, head turned to face the wall, did not appear to have stirred.

“Should I take the slop pail, Mr Grubb?” The boy had entered the room behind him.

Grubb nodded absently and slouched over to the cot. Then he remembered the food tray and nodded towards it. “Best put that on the stool over there. He’ll still be wanting his breakfast, like as not.”

Adkins picked up the tray and moved to obey the attendant’s instructions.

Grubb leaned over the bed. He sniffed, suddenly aware that the room harboured a strange odour that he hadn’t noticed before. The smell seemed oddly familiar, yet he couldn’t place it. No matter, the damned place was full of odd smells. One more wouldn’t make that much difference. He reached down, lifted the edge of the blanket and drew it back. As the blanket fell away, the figure on the bed moved.

And Grubb sprang back, surprisingly agile for a man of his age.

The boy yelped as Grubb’s boot heel landed on his toe. The food tray went flying, sending plate, bowl, bread and gruel across the floor.

Amos Grubb, ashen faced, stared down at the cot. At first his brain failed to register what he was seeing, then it hit him and his eyes widened in horror. He was suddenly aware of a shadow at his shoulder. Adkins, ignoring the mess on the floor, his curiosity having got the better of him, had moved in to gawk.

“NO!” Grubb managed to gasp. He tried to hold out a restraining hand, but found his arm would not respond. His limb was as heavy as lead. Then the pain took him. It was as if someone had reached inside his body, wrapped a cold fist around his heart and squeezed it with all their might.

The old man’s attempt to shield Adkins’ eyes from the image before him proved a dismal failure. As Attendant Grubb fell to the floor, clutching his scrawny chest, the scream of terror was already rising in the pot-boy’s throat.

1

There were times, Matthew Hawkwood reflected wryly, when Chief Magistrate Read displayed a sense of humour that was positively perverse. Staring up at the oak tree and its grisly adornment, he had the distinct feeling this was probably one of them.

He had received the summons to Bow Street an hour earlier.

“There’s a body …” the Chief Magistrate had said, without a trace of irony in his tone. “… in Cripplegate Churchyard.”

The Chief Magistrate was seated at the desk in his office. Head bowed, he was signing papers being passed to him by his bespectacled, round-shouldered clerk, Ezra Twigg. The magistrate’s aquiline face, from what Hawkwood could see of it, remained a picture of neutrality. Which was more than could be said for Ezra Twigg, who looked as if he might be biting his lip in an attempt to stifle laughter.

A fire, recently lit, was crackling merrily in the hearth and the previous night’s chill was at last beginning to retreat from the room.

Papers signed, the Chief Magistrate looked up. “Yes, all right, Hawkwood. I know what you’re thinking. Your expression speaks volumes.” Read glanced sideways at his clerk. “Thank you, Mr Twigg. That will be all.”

The little clerk shuffled the papers into a bundle, the lenses of his spectacles twinkling in the reflected glow of the firelight. That he managed to make it as far as the door without catching Hawkwood’s eye had to be regarded as some kind of miracle.

As his clerk departed, James Read pushed his chair back, lifted the rear flaps of his coat, and stood with his back to the fire. He waited several moments in comfortable silence for the warmth to penetrate before continuing.

“It was discovered this morning by a brace of gravediggers. They alerted the verger, who summoned a constable, who …” The Chief Magistrate waved a hand. “Well, so on and so forth. I’d be obliged if you’d go and take a look. The verger’s name is …” the Chief Magistrate leaned forward and peered at a sheet of paper on his desk: “Lucius Symes. You’ll be dealing with him, as the vicar is indisposed. According to the verger, the poor man’s been suffering from the ague and has been confined to his sickbed for the past few days.”

“Do we know who the dead person is?” Hawkwood asked.

Read shook his head. “Not yet. That is for you to find out.”

Hawkwood frowned. “You think it may be connected to our current investigation?”

The Chief Magistrate pursed his lips. “The circumstances would indicate that might indeed be a possibility.”

A noncommittal answer if ever there was one, Hawkwood thought.

“No preconceptions, Hawkwood. I’ll leave it to you to evaluate the scene.” The magistrate paused. “Though there is one factor of note.”

“What’s that?”

“The cadaver,” James Read said, “would appear to be fresh.”

The oak tree occupied a scrubby corner of the burial ground, a narrow, rectangular patch of land at the southern end of the churchyard, adjacent to Well Street. Autumn had reduced the tree’s foliage to a few resilient rust-brown specks yet, with its broad trunk and thick gnarled branches outlined against the dull, rain-threatening sky like the knotted forearms of some ancient warrior, it was still an imposing presence, standing sentinel over the gravestones that rested crookedly in its shadow. Most of the markers looked to be as old as the tree itself. Few of them remained upright. They looked like rune stones tossed haphazardly across the earth. Centuries of weathering had taken their toll on the carved inscriptions. The majority were faded and pitted with age and barely legible.

At one time, this corner of the cemetery would probably have accommodated the more wealthy members of the parish, but that had changed. Only the poor were buried here now and single plots were in the minority. The graveyard had become a testament to neglect.

And a place of execution.

The corpse had been hoisted into position by a rope around its neck and secured to the trunk of the tree by nails driven through its wrists. It hung in a crude parody of the crucifixion, head twisted to one side, arms raised in abject surrender.

Small wonder, Hawkwood thought, as his eyes took in the macabre tableau, that the gravediggers had taken to their heels.

Their names, he had discovered, were Joseph Hicks and John Burke and they were standing alongside him now, along with the verger of St Giles, a middle-aged man with anxious eyes, which Hawkwood thought, given the circumstances, was hardly surprising.

Hawkwood turned to the two gravediggers. “Has he been touched?”

They stared at him as if he was mad.

Presumably not, Hawkwood thought.

A raucous screech interrupted the stillness of the moment. Hawkwood looked up. A colony of rooks had taken up residence in the graveyard and the birds, angry at the invasion of their territory, were making their objections felt. A dozen or so straggly nests were perched precariously among the upper forks of the tree and their owners were taking a beady-eyed interest in the proceedings below. The evidence suggested that the birds had already begun to exact their revenge. They’d gone for the tastiest morsels first. The corpse’s ragged eye sockets told their own grisly story. A few of the birds, showing less reserve than their companions, had begun to edge back down the branches towards the hanged man’s body in search of fresh pickings. Their sharp beaks could peck and tear flesh with the precision of a rapier.

Hawkwood picked up a dead branch and hurled it at the nearest bird. His aim was off but it was close enough to send the flock into the air in a clamour of indignation.

Hawkwood approached the tree. His first thought was that it would have taken a degree of effort to haul the dead man into place, which indicated there had been more than one person involved in the killing. Either that, or an individual possessed of considerable strength. Hawkwood stepped closer and studied the ground around the base of the trunk, careful where he placed his own feet. The previous night’s rain had turned the ground to mud. But earth was not made paste solely by the passage of rainwater. Other factors, Hawkwood knew, should be taken into consideration.

There were faint marks; indentations too uniform to have been caused by nature. He looked closer. The depression took shape: the outline of a heel. He circled the base of the oak, eyes probing. There were more signs: leaves and twigs, broken and pressed into the soil by a weight from above. They told him there had definitely been more than one man. He paused suddenly and squatted down, mindful to avoid treading on the hem of his riding coat.

It was a complete impression, toe and heel, another indication that at least one of Hawkwood’s suspicions had been proved correct. Hawkwood was an inch under six feet in height. He placed the base of his own boot next to the spoor and saw with some satisfaction that his own foot was smaller. The depth of the indentation was also impressive.

Hawkwood glanced up. He found that he was standing on the opposite side of the tree to the body. The first thing that caught his attention was the rope. It was dangling from the fork in the trunk, its end grazing the fallen leaves below. The noose was still secured around the neck of the deceased.

In his mind’s eye, Hawkwood re-enacted the scene and looked at the ground again, casting his eyes back and to the side. There was another footprint, he saw, slightly off-centre from the first. It had been made by someone planting his feet firmly, digging in his heel, taking the strain and pulling on the rope. The indication was that he was a big man, a strong man. There were no other prints in the immediate vicinity. The hangman’s companions would have been on the other side of the tree, hammering in the nails.

Hawkwood stood and retraced his steps.

He looked up at the victim then turned to the gravediggers.

“All right, get him down.”

They looked at him, then at the verger, who, following a quick glance in Hawkwood’s direction, gave a brief nod.

“Do it,” Hawkwood snapped. “Now.”

It took a while and it was not pleasant to watch. The gravediggers had not come prepared and thus had to improvise with the tools they had to hand. This involved hammering the nails from side to side with the edge of their shovels in order to loosen them enough so that they could be pulled out of the oak’s trunk. The victim’s wrists did not emerge entirely unscathed from the ordeal. Not that the poor bastard was in any condition to protest, Hawkwood reflected grimly, as the body was lowered to the ground.

Hawkwood stole a look at Lucius Symes. The verger’s face was pale and the gravediggers didn’t look any better. More than likely, their first destination upon leaving the graveyard would be the nearest gin shop.

Hawkwood examined the corpse. The clothes were still damp, presumably from last night’s rain, so it had been up there a while. It was male, although that had been obvious from the outset. Not an old man but not a boy either; probably in his early twenties, a working man. Hawkwood could tell that by the hands, despite the recent mauling they had received from the shovels. He could tell from the calluses around the tips of the fingers and from the scar tissue across the knuckles; someone who’d been in the fight game, perhaps. It was a thought.

“Anyone recognize him?” Hawkwood asked.

No answer. Hawkwood looked up, saw their expressions. There were no nods, no shakes of the head either. He looked from one to the other. No reaction from the verger, just a numbness in his gaze, but he saw what might have been a shadow move in gravedigger Hicks’ eye. A flicker, barely perceptible; a trick of the light, perhaps?

Hawkwood considered the significance of that, placed it in a corner of his mind, and resumed his study.

At least the manner of death was beyond doubt: a broken neck.

Hawkwood loosened the noose and removed the rope from around the dead man’s throat. He stared at the necklace of bruises that mottled the cold flesh of the victim’s neck before turning his attention to the rope knot. Very neat, a professional job. Whoever had strung the poor bastard up had shown a working knowledge of the hangman’s tool. In a movement unseen by the verger and the gravediggers, Hawkwood lifted a hand to his own throat. The dark ring of bruising below his jawline lay concealed beneath his collar. He felt the familiar, momentary flash of dark memory, swiftly subdued. Odd, he thought, how things come to pass.

Placing the rope to one side and knowing it was a futile gesture, Hawkwood searched the cadaver’s pockets. As he had expected, they were empty. He took a closer look at the stains on the dead man’s jacket. The corpse’s clothing bore the evidence of both the previous night’s storm as well as the brutal manner of death. The back of the jacket and breeches had borne the brunt of the damage, caused, Hawkwood surmised, by contact with the tree trunk as the victim was hoisted aloft. He had already seen the slice marks in the bark made by the dead man’s boot heels as he had kicked and fought for air.

There were other stains, too, he noticed, on the front of the jacket and the shirt beneath. He traced the marks with his fingertip and rubbed the residue across the ball of his thumb.

Hawkwood examined the face. There was congealed blood around the lips. Had the rooks feasted there, too?

Hawkwood reached a hand into the top of his right boot and took out his knife. Behind him, the verger drew breath. One of the gravediggers swore as Hawkwood inserted the blade of the knife between the corpse’s lips. Gripping the dead man’s chin with his left hand, Hawkwood used the knife to prise open the jaws. He knelt close and peered into the victim’s mouth.