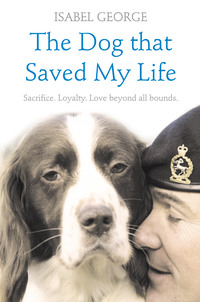

Czytaj książkę: «The Dog that Saved My Life»

Copyright

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

© Isabel George 2010

Isabel George asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780007339204

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © 2010 ISBN: 9780007339211

Version 2019-01-09

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Gander – Our Best Pal

Judy – Prisoner of War 81A Gloergoer, Medan

Caesar – A Digger and a Dog

Rats – Delta 777

Bonnie – DOG is GOD Spelt Backwards

Epilogue

About the Author

About the Publisher

To my children Luke, Lydia and Jamie…for their

encouragement and for never tiring of these

wonderful stories.

Introduction

It’s one of life’s little secrets, the bravery of animals in conflict.

Animals have accompanied man into battle since war was first waged. Over two thousand years ago Hannibal took war elephants, soldiers and supplies over the Alps. The giant animals negotiated narrow snow-covered mountain passes, risking life and limb to face the mighty Roman army. Centuries before that, the Ancient Egyptians recorded in their intricate paintings how they proceeded into battle with hundreds of horses pulling chariots, men holding hungry lions straining at the leash and falconers with trained hawks poised to do harm. The animals were there to play their part in the many military confrontations fought to secure supremacy.

Since those times, many stories have been told of the bears, camels, cats, dolphins, monkeys, mules, pigeons, rats and other creatures that have served with the Armed Forces during both world wars and beyond. Some were trained to perform specific tasks, like the dolphins deployed to detect underwater explosives, the pigeons released to deliver vital messages, mules laden with valuable supplies and rats sent running in tunnels to lay communication cables on the front line. Many others were present as mascots; the bears, cats and canaries were not trained to perform any role in particular but provided heartfelt companionship, warmth and humour, and helped create an incredible morale. Many animals have fulfilled this role, but perhaps none more universally and consistently than the dog.

The five stories featured in this book represent the devotion and unquestioning loyalty of the canine companion in the darkest days of war. From the life-saving actions of a Second World War Army mascot under fire to the undoubted trust shared between the Tracker dog and his handler during the war in Vietnam. Man’s best friend is a constant in an uncertain environment and a welcome friend. They are a testament to companionship and to partnership when lives depend on them.

Dogs continue to prove themselves to be fearlessly loyal in all theatres of war, from the hidden depths of jungle warfare in Vietnam and Malaya to the guard and patrol duties of a desert dog in Iraq or Afghanistan. Unlike the horses of the First World War dragged down in the mud of Flanders’ fields, the dog’s speed and agility has always made him an asset on any battlefield. Intelligent and obedient, the dog could be the perfect messenger, able to skip over the trenches or through a minefield faster than any man. Not only are they more successful at such tasks than a human but they, although it hurts to say it, are also far more dispensable. That has always been and will continue to be a fact of wartime life. If a dog detects a landmine he is unlikely to be harmed and his actions will protect all around him. A man is unlikely to be so lucky.

Whether dropped by parachute into enemy country, helicoptered in and out of war zones, or transported in armoured vehicles, dogs have shown their versatility in war. Dogs do what’s required of them and their keen sense of loyalty keeps them faithful to their duties and their military masters. Considering that the majority of the dogs recruited for service in both world wars were pet dogs donated for war service, their sacrifice was immeasurable. They were loaned to the War Office, trained for duty and distributed to the Armed Forces after 12 weeks’ training. The dogs then served their country, and if they survived they were returned to their owner. These dogs took this all in their stride and the lucky ones returned to life as a fireside pet in peacetime. But for every treasured family pet to be returned home safely, there were countless others who died alongside their comrades. And for all these canine heroes, there were young soldiers, sailors and airmen who had faced horror and death and who had seen those around them lost forever, who had taken immense comfort and support from these brave, devoted companions.

The war dog is not just a feature of conflicts past. Dogs are still used in contemporary warfare and have seen service in Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan. Guard and patrol dogs remain an essential element of life on any military base at home and overseas but the role of the Arms and Explosives Search dog is one that has recently come to the fore. Trained to detect and locate weapons, explosives and bomb-making equipment, these dogs are life-savers on a daily basis. They protect the life of their handler and save the lives of military and civilian personnel with each successful ‘find’. Dogs may still be listed as ‘equipment’ but no machine and no man can match the skill of a trained search dog. Wartime strategies and hardware may come and go but the skill of a war dog remains constant and irreplaceable.

Within the ranks, the war dog is regarded as nothing less than a fellow ‘soldier’, a colleague and a companion. Over the years Service dogs and mascot dogs have been decorated for their life-saving bravery in conflict. Many have lost their lives in saving others and their fellow soldiers have deemed it vital to recognize their incredible service and sacrifice to mankind.

For these animals to give so much when they are innocent in the ways of the world and war deserves recognition. These are just five stories of many, and all are awe inspiring and heart warming in equal measure. Maybe even the dogs would ask for them to be told, and they deserve to be remembered – for all time.

Gander – Our Best Pal

‘No two-legged soldier did his duty any better and none died more heroically than Sergeant Gander.’

(George MacDonnell, Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada)

‘You know Pal, you’re quite a handful these days. If you get much bigger we are going to have to move house!’ Rod Hayden laughed as he hugged the huge, black Newfoundland dog and looked into his dewy brown eyes.

Pal drooled with pleasure as he slumped down onto his master’s feet. He couldn’t help being such a big dog; after all, Newfoundlands are built that way, their thick, shaggy, black coats being the perfect protection against the freezing chills of the cruel Canadian winters. Clearly Rod Hayden loved Pal and so did his son, Jack. The dog and the boy were so close that it was sometimes like having two boisterous children around the house with only one of them having a huge fur coat. Pal was adored by his family and by every child in the town of Gander, Newfoundland.

When the snow fell on Gander it fell hard and heavy. A good snowfall would block the doorway to the house and cover the roads so perfectly that they simply ceased to exist. In the worst of it, snow banks would rise higher than the roof-tops and venturing outdoors meant piling on as much clothing as it was possible to wear under an insulated top coat. But, for the children, the most exciting thing about the snow was sledding. And who was always around to join in the fun? Pal.

Pal, who was only two years old and already almost the size of a small pony, had given Rod Hayden an idea. A while back he had seen a set of pony reins hanging on a hook in the attic and now seemed a good time to put them to good use. He had no idea where they had come from nor how old they were. He had lived in the house over ten years and had never owned a pony or a trap. The rocky tracks that meandered off the main roads in Newfoundland were unsuitable for the small hooves of a pony or the delicate wheels of a cart. But wherever they had come from and however long they had been in that dusty box in the attic didn’t matter now. Rod knew exactly what he had to do and he knew that Jack and his friends would be so excited.

It didn’t take long to persuade Pal to try on the customized harness Rod had adapted from the pony bridle. The padded band designed to go over the pony’s broad muzzle was a perfect fit and the long, covered straps slipped comfortably around the dog’s body. The reins were short to suit a child’s small hands and Jack couldn’t wait to try them out.

Ten-year-old Jack watched his father attach Pal’s new harness to the sled and he could see the dog was just as keen as he was to get out into the snow. Pal had never worn anything like reins before. He had never even worn a dog lead, but this big, friendly giant was happy to do whatever Rod Hayden wanted him to and so, after what probably seemed like forever to the young Jack, the sled and Pal were ready. ‘Come on Pal, let’s go!’ said Jack, raising the reins as Pal lurched forward with the sled lumbering behind him.

By the time he reached his friend Eileen’s house, Jack was handling the reins with confidence and he was looking forward to showing her his clever dog in harness. But in the small community of Gander it didn’t take long for every child in walking distance of the Haydens’ house to hear that Pal was giving sled rides. Soon Eileen was just one of several children queuing up to take her turn to ‘drive’. Waving and shrieking with laughter, Jack and his friends dashed along and Pal pranced around like a show pony, his long pink tongue lolling out of his mouth. No one had ever seen anything like it before.

When he wasn’t playing in the snow or taking up space in the house, Pal found a new pastime as Gander became a focus for wartime activity.

Newfoundland Airport, as it was known, had been constructed in 1936 and two years later it boasted four paved, fully operational runways. Not only was it one of the world’s largest airbases at the time but by 1940 its geographical location made it one of the most strategically important. It was North America’s most eastern-based airport and therefore perfectly placed to be a refuelling depot for transatlantic flights, and it would also give pilots the greatest range for surveillance flights over the Western Atlantic. All the Allies had to do was secure it and protect it from a possible German attack.

In 1941, the Dominion of Newfoundland offered the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) operational control of the airport. Suddenly the town of Gander was no longer just a random collection of 10 houses, a one-roomed school and an airstrip surrounded by several shed-like buildings. The Second World War was about to transform this isolated town into a strategic military airbase and place at its hub the operational activities of the RCAF. Ferry Command, the organization responsible for transporting new aircraft across the Atlantic to supply the Allied forces fighting the war in Europe, constructed a base there. The Royal Canadian Navy also selected Gander as an ideal base for a radio transmission centre and a ‘listening post’ to pick up German U-boat radio transmissions to and from Germany. Any information that could help pinpoint the position of enemy U-boats was crucial at the time as the U-boats were proving to be devastatingly successful in the war at sea.

Initially a detachment from Canada’s Black Watch regiment was posted to Gander to defend the base from enemy attack. Later the Americans also sent troops. Gander had become too important a base to risk losing or incurring any damage from enemy activity. From then on, operating as Gander Airfield, the base came to life with more hangers, more equipment, more personnel, longer runways and additions like a laundry, a bakery and a hospital.

Rod Hayden, his wife and young son Jack were one of very few families living in Gander. Jack attended the local school with 13 other children, while his father, depot manager for the Shell Oil Company, was responsible for refuelling the aircraft bound for England. This had become a 24-hour programme of activity and it would have been a lonely job if it hadn’t been for Pal, Rod’s canine shadow.

The Hayden family home was adjacent to the runway and for an excitable dog with energy to release, this was just another playground. Running to meet the planes as they landed was something Pal loved to do before he dashed to the cockpit to sit with the crew. The dog wasn’t always a welcome visitor. But that didn’t bother Pal. There were so many planes and crews going in and out of Gander that he had plenty of chances to play his tricks on unsuspecting pilots.

Often, as the ground staff worked frantically to clear the runway of snow, Pal would wait patiently for the lights to appear, illuminating the landing strip. For him it was the sign that an aircraft was on its way in and he prepared himself to greet the crew. Severe weather conditions were always a challenge to a pilot’s concentration and a row of coloured lights stretching forward to welcome the aircraft out of a snow-filled sky was a reassuring sight. No one could afford to take chances. Lives were at risk. Pal’s unscheduled ‘welcomes’ could be too much of a surprise for many pilots, and quite often the control tower personnel would receive a message that there was a ‘bear on the runway’! The operators knew what they meant and replied, ‘No. That’s not a bear. That’s Pal. He’s a dog!’

Pal was a good name for this huge, friendly dog. He was everyone’s friend and in the spring of 1941 his list of friends grew overnight when a battalion of the Royal Rifles of Canada was posted to Gander Airfield for airfield protection and security duty.

As they lived on the airbase itself the soldiers became Pal’s neighbours and they happily shared their food – and even their beer – with him. They taught him tricks like how to stand on his back legs and put his paws on their shoulders. They encouraged him to take showers; which, being a Newfoundland dog, he loved. However no one ever tried to wake Pal when he decided to take a nap in one of the bunks. He hated being woken up and it was the only time he displayed irritation or anything like a bad temper. The men learned very quickly to ‘leave this sleeping dog to lie’ as long as he liked.

Pal was a happy dog. He liked people and people liked him. But his size sometimes made him clumsy and one day while he was out with the children on the sled, Pal jumped up to greet Eileen Chafe’s sister Joan and accidently scratched her face deeply. Pal knew immediately that he had done something wrong and he licked her hand to tell her he was sorry. Although the little girl wasn’t seriously hurt, Rod Hayden took it as a sign that Pal had outgrown his time as a children’s playmate and that, combined with his often dangerous antics at the airfield, made him decide to give Pal away at the first opportunity.

So it was that Pal moved from being a family pet to becoming a military mascot. He would even have his own bunk in the barracks with the Royal Rifles. Even Jack Hayden understood that the mascot idea was a perfect solution and, the next day, Pal moved in with his new friends. He settled into his new life very quickly but he still enjoyed daily visits from the local children, and especially Jack, who missed his dog very much.

Outside of the world of Gander Airfield the war was well advanced and the soldiers sensed they might be posted overseas any day. But there was something they had to do before they left. Their mascot dog was so much a part of the place where they were stationed that the men decided to give Pal a new name that would always be a reminder of home. They decided to call their soldier dog – Gander.

Just days later the men received the news they had been expecting. They were to leave immediately: Destination – unknown.

By October 1941 the Second World War was moving into its third year and Adolf Hitler’s Germany was achieving far-flung military success and extending its power. The Führer’s indomitable general, Erwin Rommel, had the desert campaign in North Africa well under the German Army’s control. At sea, German U-boats continued to threaten British merchant shipping bringing vital supplies across the Atlantic and on land the German Army, motivated and encouraged by repeated military success, was marching across Europe, effortlessly overcoming all opposition. In that month almost all of Western Europe and much of Soviet Russia was under the military heel of Germany and its Nazi leaders.

Germany’s ever-tightening grip on Europe cast an ominous shadow over a free Britain. Only his obsession with completing the invasion of Russia could divert Hitler’s attention away from the final unconquered parts of the Continent as he prepared to march his army to the very gates of Moscow. He appeared to be ruling supreme, his armies were unstoppable and unconquerable, and the rest of the world seemed to have been reduced to a crowd of powerless and quivering spectators.

Japan, however, had its own ambitions. As Hitler’s divisions powered their way across Europe, Emperor Hirohito was not so secretly strengthening Japanese forces on land, at sea and in the air. The Japanese High Command had designs on British and Dutch territorial and mineral possessions in South East Asia, and bloody battle was clearly imminent. China was already into its fourth year of occupation and continuing battle with the Emperor’s invasion forces. If the British were not quick enough to substantially and meaningfully reinforce their Hong Kong territory with defensive forces, Japan would add Hong Kong to its list of conquests too.

Hong Kong was a thriving British colony, representing not only an economic jewel in the crown of British trading interests but also the pinnacle of British military power in the Far East. The Japanese War Cabinet had long been aware of Hong Kong’s strategic importance to their war of conquest. The Commonwealth troops already based there represented little more than a token security presence. These soldiers might have been enough to reassure the diplomatic staff and the loyal residents living and working in Hong Kong but it was nowhere near what was required to hold off the might of a battle-hardened and proven invasion force. Despite dire warnings from some of his military and political advisers, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill focused on the battles and reverses in the Mediterranean theatre and in the air and sea at home. He had been reluctant, until that point, to send a significant force to Hong Kong. But things were changing rapidly.

Within days of receiving the order to leave their barracks near Gander Airfield, the Royal Rifles were packed and ready to move out. They had been issued with their tropical kit but had not been given a briefing on what lay ahead. There was even speculation that they might be going to North Africa. For now there was one certainty: they were taking Gander with them. It was a tall order to hide a Newfoundland dog that was almost as tall as a Shetland pony and weighed as much as a fully grown man. ‘I think you’ve gone crazy,’ said one of the civilians on the camp. ‘How on earth are you going to hide that dog? You know what will happen if he’s caught, don’t you? They’ll throw him overboard if you’re at sea and if you’re on the train he’ll be put out at the next station. Then what’ll happen to him? I think you’re crazy and I think the dog needs to stay here in Gander.’

It was a brave speech but the well-meaning man was wasting his breath. He was challenging the Royal Rifles of Canada and he should have known better. Besides, who relished the idea of telling Fred Kelly, Gander’s partner, that the dog wasn’t going with them? That night the men called a meeting in the barracks. It was agreed that Fred would kick off with a request for a show of hands. They needed to know that they would have the support and co-operation of all the men if Gander was to leave with them. It took under five minutes for Fred to finish his speech and gain a unanimous vote of support. The dog was going with them. From that meeting a subcommittee of six people was formed. These were the people who would be Gander’s closest companions and the ones directly responsible for his health and welfare. If there were any major decisions to be made, these men would make them. If there was any blame to take, these men would take it. The Royal Rifles of Canada were well aware that pets and mascots were not allowed to be taken on military duty into operational areas. This was an accepted fact in the military. If they were caught there would be severe consequences. This too was accepted.

The priority was to prepare Gander for the journey. If the posting was, as they guessed, to the Far East, it would mean hiding their huge mascot dog during a train journey that would take them several thousand miles across Canada, and on a troopship that would spend many weeks at sea. There was also the problem of rations on the journey. There was only one thing to do that would protect the dog in any semi-official way: using official and unofficial influences in the military system, Gander would have to be listed as a soldier. One of the men. A sergeant. Gander of the Royal Rifles. Not only would he be on the ration strength he would also have a rank that would appear on all the transport-movement papers.

‘Sergeant’ Gander was issued with his own kitbag too. It contained all he needed for a comfortable journey and protection in battle: a special dog brush, a towel, soap, water and food bowls, a towel and everything a dog might need were gathered together. Gander was assigned a seat on the train and all the men had to do was make sure their dog was neither seen nor heard by the officers. If he was discovered it was almost inevitable that the men would be ordered to leave him behind or if they were at sea he could be thrown overboard. No one was going to let their friend down.

In charge of the rather hairy recruit was Rifleman Fred Kelly. Kelly had been a dog lover all his life and from the moment Fred set his eyes on Gander it was clear to everyone that it was a perfect partnership. A soldier at the age of just 19 Fred knew more about dogs than he did about fighting but he was proud of his country and ready to do what was expected of him. The men had very little training so for Fred and his fellow Royal Rifles there was a huge fear of the unknown. For all the men, Gander became a welcome distraction from the uncertainty that plagued them day and night. At least Fred had Gander to fill his thoughts and the dog’s care to structure parts of his day. Gander needed his food and needed to be groomed, otherwise his huge fur coat would get matted and the discomfort might cause problems. An unhappy dog was not going to make for a silent travelling partner.

In some respects the partnership of Fred Kelly and Gander was something of a physical mismatch. Fred was not a tall man, but Gander was a very large dog so when they stood or sat together it was sometimes difficult to see where the great woolly dog ended and the small-framed man in uniform began. For the journey that lay ahead of them, this was to prove a useful element of camouflage. The men knew that if Gander was found they would never see him again.

Quebec, the home of the Royal Rifles of Canada, was proud of its sons in uniform. Mobilized in July 1940, the regiment drew most of its recruits from Eastern Quebec and Western New Brunswick, which made it an English-speaking unit, with a quarter of the recruits being bi-lingual French. Quebec City welcomed the men ‘home’ and arranged a parade in their honour. It was an occasion to salute the 962 men and one dog who were about to fight for their country overseas. Each man marched straight and tall behind the distinctive figures of Gander and Corporal Kelly, who led the parade. The band played and people waved their handkerchiefs and their hats to cheer the men and their faithful mascot on their way. Smoke billowed from the train awaiting the soldiers’ arrival at Valcartier station as it made ready to take the troops closer to their war. But it was only right that after the marching, Gander should take a shower. Somehow Fred managed to locate one and the hot dog was able to enjoy his last shower for a good while.

Smoke from the train swirled around as the guards and officers mingled with civilians and soldiers on the busy platform. Fred Kelly and his friends viewed the situation and tried not to look as nervous as they felt. The officers were on the look out for deserters or anyone trying to smuggle an animal mascot aboard. If only Gander had been a monkey or a kitten or something smaller than a full-grown Newfoundland dog, hiding him would have been easier. But the men were just about to discover that their dog was the most obedient creature on earth, and the cunning plan they had hatched in the relative security of Gander Airfield was about to be put to the test.

Within seconds of marching into the station the men were lining up to board the train. Fred Kelly tightened his grip on Gander’s leash as the rest of the detachment mingled to shield the dog from view. Gander wasn’t used to crowds like this and Fred could sense the big dog’s unease. All the time they were hoping no one would look down and see four hairy black paws on the ground.

Roll call sent shivers down Fred Kelly’s spine. But he need not have worried. It was to go just as they had practised. Whenever Sergeant Gander’s name was called, Fred piped up ‘Sir!’ and two of his friends started a scuffle to distract the officers while the dog was bundled onto the train. The plan worked perfectly! Now all they had to do was find their seats before any official took a backwards glance to double-check the large fur-coated recruit with the lumbering walk.

Although Sergeant Gander had a seat on the train, Fred decided to err on the side of caution and kept Gander lying on the floor for the time being. The dog was used to the floor; if he couldn’t get a bunk he would lie quietly at his master’s feet. The noise and bustle of the officers and men of the Royal Rifles of Canada and the 911 Winnipeg Grenadiers who boarded the train were enough to disguise the sound of the mascot dog’s heavy panting. But from this point on, the men had one thought – making sure their mascot stayed with them all the way. Fred Kelly’s caring approach and the tone of his voice saying, ‘That’s it, Gander old chum…quiet now…good boy…’ reassured the big dog that he was in safe hands.

The train was scheduled to stop in Ottawa, its third stop on the journey to Vancouver on the west coast. Brigadier Lawson, a veteran of the First World War, stationed in Canada’s capital and a career soldier, was to board the train as commander of ‘C’ Force – the newly created fighting force comprising the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Royal Rifles of Canada, attached military support personnel and one mascot dog called Gander.

It was a three-day train journey and Gander was the perfect travelling companion. There was not an awful lot for a dog to do on a train and the men were afraid Gander would get bored and noisy and blow his cover but, as always, the fears can be greater than the reality. While the men played cards or disappeared into their own worlds to write letters to loved ones, Gander stayed with them. Sometimes he chose a lap to lie on or, if someone left their seat for too long, he would stretch out and fall asleep for a while or at least until the rightful owner gave Gander a gentle nudge to leave. No one minded Gander plonking his big slobbering jaws on their lap. If he decided you were going to be the play partner for the day it was best to give into it because he would never let a soldier have any peace until they had played at least one game of tug of war with a sock. The most difficult part about having Gander along for the ride was the impossibility of taking him for walks. Gander was very patient but he was a big dog and it wasn’t good to keep him cooped up in the train, but the men had no choice. They had come this far, so they made sure that Gander had long play sessions with improvised toys and a huge amount of tickles and play fights. Unable to enjoy his favourite thing of all, a shower, Fred ensured that he was washed down and that he had long grooming sessions too. Toileting was difficult for Gander because at almost three years old he was used to looking after himself. This was like puppy training all over again. The good thing was, Fred Kelly was used to dogs and had the inbuilt patience to coach Gander through the necessary paces. He also had to have everyone else’s support to make it work and in case of ‘accidents’. Fred created a toilet area for Gander in one of the washrooms. After a few days it was clear what he needed to perform and when, so Fred accompanied the dog and dealt with it all. It was rare that anyone else had anything to do as Gander was very ‘regular’ and Fred was never far away. If there was the odd accident the men knew what to do.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.