Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Stormswept»

Dedication

To Amber Ia

Contents

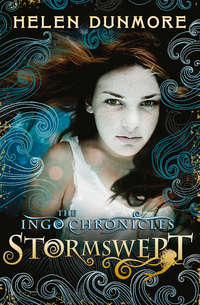

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Copyright

About the Publisher

orveren! We’ll get caught! Let’s go back and wait for the boat!” shouts Jenna, but I keep on running as if I haven’t heard. We’re nearly half-way across the causeway to the Island. Jenna won’t turn back without me. Sure enough, I hear her feet splashing over the cobbles behind me.

orveren! We’ll get caught! Let’s go back and wait for the boat!” shouts Jenna, but I keep on running as if I haven’t heard. We’re nearly half-way across the causeway to the Island. Jenna won’t turn back without me. Sure enough, I hear her feet splashing over the cobbles behind me.

“Morveren!”

We can make it, I know we can. The tide has reached Dragon Rock and is pouring round it. We’ll get a bit wet maybe. I’m not turning back to wait for the boat now.

“Morveren!”

I don’t stop, but this time I look back. My sister is standing stock still on the causeway. The wind flails her hair over her face and the creeping water is already at her feet. I want to keep running but my feet won’t do it. Maybe she’s got a stitch. I race back to Jenna, and grab her hand. It’s cold, and her face is panicky. I pull her hard, but it’s like pulling a statue.

“We’ll drown if we stay here! You’ve got to run!”

The tide is coming in behind us too. We can’t go back to the mainland now, even if we want to. That’s the way the tide tricks you. When you’re looking ahead, the water slides in stealthily from behind. But we can still reach the Island if we run as fast as we can. Every second counts. I yank Jenna’s arm and she unfreezes.

“We can’t go back now, Jenna. Look, it’s too deep.”

She knows it. Jenna’s the sensible one usually, but if we stand here much longer it’ll be too late to go on as well as too late to go back. I’m hot all over with anger at myself. We should have waited for the next boat. Jenna wanted to, but I wouldn’t. Dad will be so angry if we get caught by the tide. There’s a refuge a hundred metres ahead but if we have to climb up there someone’s got to bring a boat out to rescue us and everyone will know how stupid we’ve been.

We race as fast as we can over the causeway cobbles. Our feet slip, slide and splash. The tide’s not racing, but it’s coming in relentlessly, pulse after pulse. The stones are almost underwater now. Here’s the refuge, standing firm with its ladder and iron handholds. It’s only just been rebuilt because the old one was swept away by last winter’s storms. We pound past it without slowing down. We don’t have to discuss it because Jenna feels the same as I do. We’re not going to be stuck up there, waving for help like tourists. There’s no mobile reception out here, or on the Island.

Jenna and I run on side by side, clutching hands. If anyone saw us we’d get in so much trouble. It’s only because I had a detention and Jenna waited for me that we were both late. The sea’s putting out claws of grey water now, slopping over our feet. Surely the causeway will start to slope upwards soon, to the Island shore. Rain’s driving in too, big flapping sheets of rain that hide the rocks. But we’re nearly there. All that scares me is the way the water keeps on getting deeper. If it rises past our knees there’s a danger that the tide will be strong enough to push us off the causeway into deep water. We could be swept away.

The sea is pushing us now. It wants to win. You only have to make one mistake, Dad always says, because the sea never makes any. All our lives we’ve been taught to respect the sea. Dad would go mad if we got swept away.

Jenna stumbles. My shoulder wrenches as I drag her upright.

“Quick, Jenna!”

But as I pull her I lose my balance and my foot turns on the cobbles under the water. This time it’s Jenna who hauls me back.

We’re nearly there. It’s going to be all right. My legs hurt because it’s so hard to run when you’re almost knee-deep in water. We wade and slither and stumble, shoving ourselves forward as if we’re running in a nightmare. The water licks our legs hungrily, but it’s not going to get us this time, because suddenly, with a rush of relief, I see that the outline of the cobblestones below us is getting sharper again. The water’s falling. The causeway’s rising. We’ve made it.

At that moment the strangest thing happens. I stop fighting the swirl of the sea around my legs. I slow down. The smell of salt fills my head as a curtain of rain moves across my field of vision and hides the Island. A herring-gull swoops down, combing the air above my head. The tide shoves in, almost lifting me off my feet.

And for a moment I want to be lifted. I want to know where the surging tide will take me. If only I could fly through the water like that gull which is skimming away, free, towards the horizon… My mind fills with longing and for a few seconds everything else is crowded out. Even Jenna, my twin sister, closer to me than I am to myself – Jenna vanishes from my thoughts. Grey water, glistening water, the smell of salt—

But Jenna’s tearing at my hand. “Morveren! Morveren!”

The feeling fades, like waking from a dream. I try to snatch it back as the gull screams in the distance, but it’s gone.

“Hurry, Morveren!”

We wade through the shallows as the causeway rises and the grip of the tide releases us. It’s just water now. We’re safe, and suddenly the sea is cold, freezing cold, and all I want is to be in front of the fire at home.

Panting and wet, we haul ourselves up the last few metres, scramble up the slipway and collapse against the harbour wall, hoping no one will be about. But of course, Jago Faraday’s lounging around as usual, even though it’s now pouring with rain. There’s nothing he likes better than someone else having a bad time.

“Cutting it a bit fine, my girl,” he says to me, frowning as if it’s all my fault that we nearly got caught by the tide. “You keep your sister away from the water.”

To say that Jago has favourites is an understatement. He loves Jenna and hates me. He calls us the good ’un and the bad ’un. It’s supposed to be a joke – the kind of joke which is not funny when you are the butt of it.

“You been getting your sister into trouble again.”

Jenna is exactly the same age as me: in fact she is twelve minutes older. So how is it that I’m always supposed to be the one who leads her into trouble? But I don’t say this. Backchat will make him more likely to tell Mum and Dad that not only have I nearly drowned Jenna, but I gave him lip as well.

“I shan’t tell your mum and dad,” says Jago, as if he’s read my mind. “I can keep a secret.”

I’m relieved in a way, but I don’t want to share any secrets with Jago Faraday. He’s a spiteful, mean old man. But Jenna smiles at him, and then Jago’s face changes completely as he smiles the creaky old smile that only she ever gets. “You go on home and warm yourself, my maid,” he says to her, in his special Jenna voice. Never mind if I die of pneumonia, as long as Jenna’s warm. I look sidelong at Jenna, and pull a face, but unfortunately she is still smiling at Jago.

Our school shoes are sodden, and our tights too. Our coats are not too bad.

“If we stuff our shoes with newspaper and put them near the stove, they’ll dry out all right,” says Jenna. “Lucky it’s raining. Mum won’t notice.”

“I should have skipped detention. No one except Mr Cadwallader would give a detention on the last day before half-term.”

“You’d have got a double one.”

“Yes, but I wouldn’t have had to do it for more than a week… Jenna? Have you ever had a detention?” I know she hasn’t.

“Well… I haven’t yet,” says Jenna cautiously, because she doesn’t want to make me feel bad.

“You haven’t ever, you mean. Do you realise how much easier my life would be if you weren’t so good?”

“Mum won’t ask why we were late. We’ll just say we missed the boat.”

“OK.”

Mum will find out anyway at the end of term, when she sees my report. They always put detentions on reports, but that’s a good long way off and anything could happen before then. If only Jenna didn’t bring her report home at exactly the same time, mine wouldn’t look so bad. If my parents compared my report with Bran Helyer’s, for instance, they’d be quite happy. Ecstatic, even…

“Couldn’t you throw a few crisp packets round the classroom, Jen? Or tell Mr Kernow you didn’t fancy doing your maths homework?”

Jenna stares at me. “Why would anyone do that?” is written all over her face.

“Bran was in detention today,” I say casually.

Jenna’s face shadows. It’s complicated. All through primary school she and Bran were friends. No one else liked him, though he had a gang for a while. But the gang got too violent even for the people who were in it. Soon, Bran was a gang of one, and everybody left him alone.

Mum used to say, “Bran doesn’t have much of a life, with that father of his,” as if she were sorry for him. No one else was: they were too scared of him. But then something changed between Jenna and Bran. People think that twins tell each other everything, but that’s not true. Jenna doesn’t need to tell me, anyway. I can feel the difference in her. She might not be friends with Bran any more, but if someone talks about him, Jenna always reacts. It’s not obvious, because nothing with Jenna is obvious, but it’s there. I can sense what Jenna’s thinking most of the time and I know from the way she looks at Bran (which, being Jenna, she rarely does any more) that even if they aren’t friends, there’s still a link between them. But Bran is too much of a bad boy for Jenna now.

“Was he?” says Jenna now, in a carefully neutral voice.

“What?”

“In detention. Bran.”

“Yeah. He walked out halfway through though. He’ll get suspended again, I think.”

Jenna flinches.

“Bran won’t care about a suspension, Jen.”

“His dad hits him,” says Jenna in a low voice. She may not be friends with Bran any more, but she still knows a lot more about him than anyone else does. But the fact that Bran’s dad is violent isn’t exactly news. He used to live on the Island, when he was still married to Bran’s mum, because she’s an Islander, like us. She’s gone away, upcountry. I think Bran still sees her, but I’m not sure. I look at Jenna. She’s frowning and her face is full of worry. Jenna hates any kind of violence. Even the kind of fights boys have in primary school used to make her hide away in the girls’ toilets.

Mum and Dad aren’t at home. Mum’s left a note telling us that they’re rehearsing with Ynys Musyk in the village hall. Digory’s gone with them and there’s a stew in the oven. Ynys Musyk is our island band. Everybody plays in it more or less, although not Jago Faraday. The only time he even sings is at funerals, very loud and very flat. There’s a reason why our band is so important, but it’s complicated. We don’t usually talk about it to outsiders, because they wouldn’t believe it. They’d probably think it’s just a legend, one of those stories for tourists.

Digory is our little brother. He’s seven and he plays the violin. I do too, but Digory’s playing is something different. In the summer, when the visitors come, they hear Digory practising and they tell Mum and Dad that something ought to be done for him, as if Mum and Dad are too stupid to know how good Digory is. (Some tourists think that because there’s no mobile signal on the Island, and we don’t have broadband, that we are out of touch with the real world.) They say that Digory ought to go away to a music school on the mainland, to develop his talent. But Mum tells Digory to go and practise away down by the shore where nobody will hear him. She doesn’t want Digory leaving home, and nor do any of us. It’s bad enough that we have to go to school on the mainland once we’re past the Infants, because there aren’t enough of us to be educated here. At least we come home every night. The music school would be far away upcountry and Digory would have to board there. He would hate that.

When you grow up on an island you don’t ever want to leave it. It gives you such a safe feeling when the water swirls all around and no one can get to you. No, not safe exactly… Complete. As if you have everything that you will ever need, and nothing that you don’t need. Even though a causeway connects us to the mainland at low tide, we are still a true island. Sometimes in winter, when there’s a storm, we can’t go to school for days. I love the season of storms. No one can reach us then. We are supposed to keep up with school worksheets and reading, but even Jenna doesn’t bother.

Some people say that the sea is rising year by year, and the coastline will slowly crumble away as it retreats from the oncoming water. If that happens, we’ll be cut off from the mainland even at low tide. I’d like it, but other people say we couldn’t survive like that, and we’d have to build up the causeway, even though it would cost millions. Otherwise the tourists won’t come, and most of our income will be gone. It’s hard to make money here. The only jobs are fishing and tourism, unless you’re a doctor or a nurse or something like that. Mum has a part-time job in the post office.

Jenna stuffs our shoes with newspaper and washes the salt water out of our tights, while I put on potatoes to go with the stew. It is dark outside now, but inside it’s warm and you can smell the bread Mum made earlier, which is cooling on racks in the kitchen, ready for the freezer. The wind is blowing hard. The sea is beating up, and even with the door and windows closed we can hear the waves thump on the rocks. There will be deep water now where Jenna and I stood on the causeway. I shiver. Sometimes it frightens me, how quickly the world can shift between safety and danger. I want to retreat into a small, secure space. But at other times, risk pulls me like a magnet. I remember that strange feeling, when the sea almost lifted me off the causeway. I wanted it to lift me. Where did I want it to take me?

Maybe Jago Faraday is right, and I’m leading Jenna into trouble. She is so cautious and sensible. She would never take a risk unless I did, but then she would always follow me.

“You should dry your hair, Morveren,” says Jenna. “It’s dripping down your back.”

We both have long dark hair that reaches almost to our waists. When we were little Mum used to give us different partings, so that other people knew which one of us they were talking to, and she would buy blue hairbands for Jenna and green for me, because those were our favourite colours. We don’t bother with any of that now. If people don’t see that our characters are completely different, and that makes our faces different too, then let them go on mixing us up.

A thought strikes me. “You could do my detention for me next time.”

“It would still get written into your school diary,” says Jenna, who has clearly worked this out long ago. Otherwise, she would do the detention for me, I think. Jenna’s like that.

There’s a bang at the window, and I jump.

“That shutter’s come loose again,” says Jenna calmly.

“I’ll fix it,” I say, and before she can offer to help, I slip out of the door.

The night is wild now, full of wind and rain. All the cottages on the Island have shutters, to protect the glass in the windows from winter storms. I grab the loose shutter as it slams against the sill, and wedge in the hook that holds it. The wind whips my hair and I taste salt on my lips. Sometimes, when there is a storm, salt spray flies right over the Island. We go down to the headland and watch the waves battering the Hagger Rocks. I could go there now. I can find my way in the dark. I know every stone of the Island – we all do.

The wind whirls round the corner of our cottage. It’s pushing me, folding around me. The branches of our tamarisk tree whip above my head. How strange – I’m not by the window now, I’m already at the gate. The wind is shoving me along as if it knows where it wants me to go. My hand is on the latch. I open it, and now the wind seizes hold of me, carrying me with it, almost lifting me off my feet.

hen a storm is raging, I feel ten times more alive. Storms are in my blood, because of the way our island came to be, and the way I came to be here.

hen a storm is raging, I feel ten times more alive. Storms are in my blood, because of the way our island came to be, and the way I came to be here.

Long ago, there was no Island, and no wide bay full of sea. Mainland and Island were all one. There was solid land here, where our ancestors built a great city. It had wide streets and rich houses, and a hall as big as a cathedral, where they held gatherings. Everybody in that city loved music, and they would come together to play and sing and dance all night long, until they went home in the grey light of dawn.

But one night everything changed. The hall was packed with people. There was a great gathering, with music that was going to play all night long. There were fiddles and bodhrans, bagpipes, whistles and harps. The music flooded out, and in spite of the crowd everybody was dancing. All you could hear was the skirl of the band and the stamp of hundreds of feet.

That’s why nobody heard the change in the wind. It had been blowing a gale all day, but our ancestors were used to gales and bad weather, just as we are. They didn’t let it stop their celebrations. The wind grew louder and louder, louder than any wind that had ever been heard in that land. It roared around the roof like an express train, and as it blew the sea began to move.

It moved slowly and stealthily at first, as if it didn’t want to alarm anyone. Only one person saw what was happening, and that was a boy who was perched up on his father’s shoulders so that he could see everything. The windows were high up in the walls and only the boy could look out of them. He turned, just as the moon broke free of the raging clouds and shone out. The boy saw the wild, foaming waves flatten as if a giant hand were pressing down on them. And then, very slowly the sea began to move backwards, as if it were swilling away down a giant plughole.

The boy blinked. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

“Dad! Dad!“ he shouted. “The sea’s going backwards!”But his father didn’t hear him above the noise in the hall. The boy stared with his mouth open. In the far distance, where the sea had gone, he saw a wall of water, higher than any wave he had ever surfed, higher than any house, far higher than the walls of the great hall. It was as black as night with a crest of curling foam. It was moving, but not backwards now. It was coming in towards the land.

The boy cried out, so loud that this time his voice was heard above all the noise in the hall:

“The sea! The sea’s coming!”

People close by frowned at him for screaming like that. The band kept on playing, but one man heard the terror in the boy’s voice, and he went to the doors at the back of the hall and pulled them open. Outside it was almost dark. The air streamed with spray until it was hard to see anything. But the moon shone out and then the man saw what the boy had seen: a wall of water advancing slowly but with terrifying force, as if nothing in the world could stop it. The hair on his scalp prickled. A cold wind roared through the hall from the open door. At the same moment the man’s voice rang out like a trumpet:

“The sea’s coming! Run for your lives!”

The fiddler stopped playing, with his elbow raised. Everyone stood frozen for a second and then a wave of panic rushed through the crowd. People began to shove towards the door, grabbing their children and their loved ones. Some clambered up to the windows and there was the crash of breaking glass, and then a scream. The blind fiddler held his fiddle high. Whatever happened, he would protect what was most precious to him. He couldn’t see what was happening but he could smell the panic and hear the cries of parents calling for their children:

“The sea’s coming! Cador, where are you? Tamasin! Tamasin!”

“The sea’s coming! We’ll be trapped!”

They’d lived with the sea all their lives. They knew all about storms, but this they had never seen. Those at the back of the hall could see the wall of water rushing towards them, reaching for them, as they fought to get out of the doors.

The boy on his father’s shoulders saw the blind fiddler holding his fiddle high. He bent down and shouted into his father’s ear above the roar of the water and the screams and cries:

“Father! We must help him! He can’t find the door!”

In a few strides the boy’s father made his way along the wall, away from the crowd pressing towards the doors. The jam of people was too dangerous now, the father judged. His boy would be crushed. He would try to get the boy to safety another way, and the blind fiddler, if he would come with them.

They begged the fiddler to follow them, but he refused.

“You’ve got your young one,” he said. “Take my fiddle and run for the highest ground.”

The blind man put his fiddle into the boy’s arms, and the boy held it high. The father climbed on a chair, smashed a window and knocked out the glass with his boot. He lifted his boy high, still holding the fiddle, and put him up on the window ledge. The boy clung to the stone frame. Outside it was dark and the ground was a long way down.

“Jump!” he said. “Jump! I’m coming after you!”

The boy jumped. He landed on his feet then stumbled and fell on one knee, but still he held the fiddle safe. He looked up for his father, but his father shouted, “Run! Run, Conan! I’m coming after you! Run for the highest ground! I’ll be right behind you! Run!”

The boy obeyed his father, and ran. He could hear the gathering roar of the sea, and ahead of him he could see the shadow of the Castle Mound, which was the highest place for miles. He held the fiddle in his arms and ran until his breath burned in his lungs, and his heart was pounding. The sea was behind him. He didn’t dare to turn. It was like a wild animal, roaring at his heels. In front of him the bulk of the Mound grew clearer. He was almost there. Just a few more breaths, just a few more desperate pounding steps. His feet were on the rock. He was stumbling, falling, with the fiddle held high above his head to keep it clear of the water. At that moment an arm reached out and dragged him up on to the rock, and held him tight. He was safe on the Mound.

But where was his father? He looked behind him and saw the wall of water below him. In the moonlight he saw hundreds of figures running for their lives, but the water was gaining on them. His father had no one to lift him up to the window frame! How would he escape? Conan cried out in horror as he realised the sacrifice his father had made. He thrust the blind man’s fiddle into the arms of a woman who was shivering beside him.

“Keep it safe!” he shouted, and he turned and plunged back downhill.

The wall of water broke long before it reached the boy. Its force swelled over the city and swept away everyone in its path. The great hall filled with salt water, and out of all the people who had played and danced that night, only a handful ever reached the safety of the Mound. The power of the water spread out over the land, covering it, turning miles of fertile fields and a great city into a bay full of raging sea. The water boiled with wreckage. The air was filled with sobs and cries and curses, as the people of the city gave up their lives.

But the boy was still alive. The water seized him, hurled him high into the air, and then plunged him down into its depths. His lungs were bursting but he kicked and fought his way back to the surface. All his experience of growing up by the sea came to his aid as the currents of the storm clawed at him.

“Don’t panic,” Conan told himself. “Don’t fight the current, go with it until you can swim across it.”

Everywhere around him there was blackness. Cloud had come over the moon and Conan couldn’t even see where the great hall had been. He shouted again and again for his father, as he struggled to keep afloat. No one answered. Salt water filled his mouth and he coughed and spat and choked. The sea was too strong. It had got hold of him and it wasn’t going to let him go. Bright speckles danced in the blackness in front of his eyes and he remembered his father’s words,

“You only have to make one mistake, Conan, because the sea never makes any.”

Another wave broke over his head, pushing him down.

At that moment a strong arm came around him. Conan was rising up to the surface again. There was air and he could breathe. Someone was holding him up, holding him so strongly that the sea had no power to pull him away.

They were swimming across the current now, more powerfully than the boy had ever swum in his life. The waves were calming, and the moon had once more pushed the clouds aside. Ahead of him, Conan saw the Mound rising against the sky. At that moment the grip on him loosened. The boy turned and saw a face he didn’t know, with long hair streaming around it like seaweed. It was not his father who had saved him. The man pointed ahead, as if showing Conan the way he must go to safety. Land was very close. The boy trod water, and then his foot brushed against sand. Coughing and choking, the boy dragged himself into the shallows and lay there gasping for breath.

When he looked up, the man who had helped him had disappeared.

Conan never saw his father again. The other survivors became his family. As dawn broke they huddled together on the Mound, with the wide, grey, stormy sea all around them. Castle Mound had become an island. Their city and their homes had vanished beneath the waves. The survivors had no possessions, except for the clothes they were wearing and the blind man’s fiddle. But they had their lives, to start all over again, and they had their memories.

They remembered the music they used to play. As time went on they got other instruments from the mainland: bodhrans, flutes, bagpipes. They played the music of the lost city, even though it made them sad at first. They remembered what their lives had been like, and they built a new community, and a future for themselves and for their children, on the Island. Conan grew up, and became a great fiddle player. People said that he played almost as well as the blind fiddler who drowned in the flood.

Conan never forgot the arm that had reached out from the water and brought him safe to land. No human arm could have had the strength to hold him against that wall of water. No human being could have swum against the current and brought him to the Island.

Years later, when Conan had children and grandchildren of his own, he passed down to them the story of his rescue. He wanted it to be remembered for ever, and it is. I remember it, Jenna and Digory remember it. Our parents told us the story just as their parents told it to them, and back and back for as long as anyone knows. Conan is my ancestor. My great-great-great-great… I don’t know how many greats. He always kept the blind man’s fiddle safe, and we have it safe still. We call it Conan’s fiddle.

When Digory is old enough for a full-sized fiddle, that’s the one he will play. It’s too big for him now. Sometimes he takes it out of its case, just to try it, and to stroke the rich curve of the wood. Maybe some of the blind fiddler’s spirit has stayed in his instrument, because Digory says it is full of music. If anyone can find that music, Digory can. After a while we wrap the fiddle again in its blue velvet cloth, and put it back in the case. Some people say that if the fiddle is ever lost or broken, it will be the end of our island, and we should keep it stored away somewhere safe and never play it. Mum says that is rubbish. Fiddles are for playing, just as life is for living.

There is another legend about our ancestors, but it sounds so weird that not many people even talk about it, let alone believe it. They think it’s just a story that was made up to comfort the survivors, after the flood. But I’m not so sure… Maybe I believe it because Conan is my ancestor, and he was saved by a man with long hair like seaweed and the power to swim where no human being would be able to swim.

This is the legend. They say that when the wall of water swept away all those hundreds of people, not all of them drowned, even though they went down and down into the water, so far that they couldn’t rise again. A few of them – a very few – survived. Their lungs were bursting and burning for air. They couldn’t hold out against the water any longer and there wasn’t a chance of getting back to the surface. They had to breathe in.

They did breathe in. Seawater filled their lungs and salt swept through every vein in their bodies. They should have died but the sea didn’t kill them. They were filled with agony at the first breath of salt water, but then they took a second breath, and a third. Each time, their breathing grew easier. Their bodies took in the sea and became part of the sea, and they didn’t die.

It’s only a legend. Nobody ever saw one of those people who had been changed so that they could live in the sea. They could never come back, because they belonged to the sea now. Their skin changed until it looked like the skin of a seal, not the skin of a human being. They could swim as far and as fast as dolphins. They had their own language, and their own world.

Once Jago Faraday was out in his boat, night-fishing, over the place where the drowned city is said to be. It was a calm night and the sea was flat. There wasn’t a breath of wind. Jago dropped his anchor, and as he did so he looked down into the depths of the water. He saw shadows moving far below the surface.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.